The Country Idiom of Hip-Hop

How trickster tales, diasporic toasts, and James Brown shaped a genre

By Imani Perry

One Small Step, 2019, oil paint, sand, vinyl glitter on canvas (48” x 48”), by Jamaal Peterman © The artist. Courtesy Vigo Gallery, London

My chest still swells when I hear Big K.R.I.T.’s 2014 “Mt. Olympus.” I put it on at least weekly. I think that’s part of what it means to grow old in hip-hop. You don’t listen seasonally anymore, to what is new, at least not as a matter of ritual. Instead, you listen to what you loved and what continues to speak to you long after its newness has worn off. I am a fifty-year-old Black American woman. This means that hip-hop is one of the soundtracks to my life. And more than most, I have a Rolodex of rhymes in my head that are triggered with the slightest reference point. But there’s something about that particular track: the way it marks not only a Southern but a country geography to the art, one that has little to do with the standard professional accolades but everything to do with mastery of craft and an active connection between emcee and the people, that does it for me. It tells a story, suppressed but essential, of the origin of hip-hop.

Although I can remember the first hip-hop record, and even the first time I heard “Rapper’s Delight,” I am the first to admit I began on the outskirts of the art. I was not a New Yorker, and even as a teenager in the Northeast, I missed each summertime season of hip-hop (the best season for new music!) because I was in Chicago where house music was king, and Birmingham—my birthplace—where r&b and soul held sway much longer.

I loved hip-hop though, from the first time I heard it. Full of both ideas and feeling, the pulse of my generation, the children who were left after Civil Rights were won and then lost. And I felt it had something to do with me long before I ever set foot in a hip-hop show. Even though I couldn’t rightfully claim the geographies it shouted out, it helped me organize my thoughts about the politics of race, the political economy, gender, place in the world, and generation. It gave me a language for falling in love with the word and writing, and I guess that’s probably why my first book was about hip-hop. Decades later, my college student son is in a course about hip-hop history and as often happens the past seems to kaleidoscope into the present. Hip-hop is everywhere. And I wonder about the simultaneous feeling of deep intimacy and remoteness that always was and perhaps always will be part of hip-hop to me. Where does that tension come from?

I have an answer, I think. It’s about where the music came from and the name it isn’t called.

Let me begin at the beginning.

We, who were not in or of New York, and especially we who were of that place endlessly marked out of step, “The South,” heard something new and something we knew simultaneously when hip-hop emerged. But it wasn’t so easy to testify to. Because by the time Kool Herc was collaging the sounds he’d heard on turntables in his native Jamaica and his best friend Coke La Rock was chanting over them, much of these Black folks’ past had been discarded to make a new home in New York City. By then toasting ballads, born in the early twentieth-century Southeast and repeated by Black radio DJs across the country, had become an inspiration for Count Machuki. Machuki innovated the way toasts would be remixed in Jamaica for the dance floor. Toasts were also re-made into comedy records by entertainers like Arkansas native Rudy Ray Moore, who built his career in Los Angeles, and then mixed yet again with immigrants and migrants to the west coast. By the time all this became the root of rap records, a standard practice of mocking country folk was already settled. As early as 1948, the great Oklahoma-born and Tuskegee, Alabama–educated writer Ralph Ellison looked pityingly on those who shared his country roots and were trying to make their way in New York:

…in the North he surrenders and does not replace certain important supports to his personality. He leaves a relatively static social order in which, having experienced its brutality for hundreds of years—indeed, having been formed within it and by it—he has developed those techniques of survival to which Faulkner refers as ‘endurance,’ and an ease of movement within explosive situations that makes Hemingway’s definition of courage, ‘grace under pressure,’ appear mere swagger.

Years later, this is how the new art form, hip-hop, was seen by many. As mere swagger. For their part, the swagger was seen as having little to do with where their parents and grandparents had come from. Even those among them who had been sent to country homes for summers were not eager to claim their origin as source. Think about your uncle saying, “You don’t know nothing about this right here…” before grooving to a classic song. It is as if, instead of reminding him you’d heard it your whole life, you just said, “Sho don’t,” and kept moving. That is what it was, a refusal of whole-body laughter, drawls, and the markers of wisdom without slickness.

But country ways snuck in and stuck to hip-hop. Thank goodness for writers and scholars like Kiese Laymon, Regina Bradley, and Zandria Robinson, who have testified to this. Consider this piece my effort to follow them, and to repeat and recast something I tried to say in my 2004 book Prophets of the Hood. In that text, I traced a genealogy of hip-hop going back to the plantation and to West African aesthetics, noting the consistency of forms and sound ideals. What I didn’t account for was the role of sensibility. And that is at the heart of what I would call a country idiom in hip-hop.

For decades, scholars of Black studies grappled with the concept of retention, as it related to West African culture. How much was intact after the slave trade, they debated. But I have grown to think that retention is a deprived concept. Of course, people hold on to the past. Culture is arguably best described as collective ways of doing. It’s never born at a single moment. It is collaged from what folks know, learn, and feel, together. Culture is never static. Rituals shift, some habits are discarded, new ones are taken up, and ways of doing things change. And yes, some ways are held on to tightly. Some of that holding on is deliberate, most is not. People naturally keep what they need. And that’s part of why country remains in hip-hop. It’s a matter of word, sense, and sound.

The word is clear as a bell. Storytelling of the plantation South, what Zora Neale Hurston as anthropologist (and my mama as a woman from Alabama) called “telling big lies,” is at the heart of hip-hop. Heroic tales of subversive slaves who turned the tables on the master class with power and wit were prevalent. Captives held fast to land, imprisoned on it, admired those who could turn power on its head, even if only in fabulist form. In the best stories, they could travel and transcend circumstance. That practice was rooted in an even older grammar. West African animal trickster tales took on a new world urgency. B’rer Rabbit was neither predator nor powerful, but his wit gave him the upper hand when he faced adversity. The Signifying Monkey, in repeated extended rhyming ballads, talked shit about big animals Elephant and the Lion, unleashing their wrath. But the smaller yet more clever creature always managed to escape harm. These stories were not just morality tales, they were a kind of freedom dreaming.

Many expected that migration would mean these types of stories would peter out. Alain Locke, who described the New Negro Renaissance in Harlem of the 1920s, was fond of announcing how Black folk culture was dying. The old ways would be lost, he wrote, so we’d better document what they had been. The documentation was worthwhile even though people like Zora Neale Hurston and Sterling Brown, who argued back that folk culture was, indeed, intact, appear to have been closer to right than Locke. The documentation, whether it’s of stories, or blues, or ballads, makes clear how much has remained. It had to, because, as Faulkner said, the past wasn’t the past. All of that movement on trains, buses, and boats, all of that searching for something and someplace new yielded a painful truth: a captive condition followed them across borders and zones with different tongues and new laws and fewer trees.

As many critics have noted, hip-hop emerged at a telling moment. The Seventies were the dawn of mass incarceration and deindustrialization. Ghettoization persisted. Held captive yet again, telling big lies came back full throttle. Hip-hop grew with fantastic tales of beating circumstance, stories that fed hungry souls. This time the kids, not the grown folks, were telling them. These were kids who witnessed dreams and their deferral. Kids who could remember hearing, “Ain’t no stopping us now,” “Wake up all you sleepers,” and “I know a place where ain’t nobody crying.” They’d felt the joy of big Afros and stacked heels and had been told we were on the move. And just as they began to see the world beyond their households, they recoiled at what crack did to mothers, and cops did to sons, and fathers locked away, and their buildings burned for insurance money, and work disappearing. Sanely, they held on to shreds of the hopefulness of their childhood.

The country hero sound of James Brown was the backdrop. Augusta dripped from his mouth. He hunched down low, a cape like a death shroud was draped over his shoulder before he would shoot up, knocking off the cape and returning to his ebullient corporeal performance. He was more hot than cool, always willing to break a sweat. He was appropriately theatrical—country folks love to play-act, but reject posturing. Though Brown’s flashy embodiment was deemed inappropriate for imitation to New York kids who had adopted a learned watchfulness, they kept him as the backdrop. Nostalgic youth kept the dashed, earnest hope of just a few years prior within a beat’s reach, holding fast to a time before the 1980 presidential election, when the country voted against Black freedom dreams.

If you want to see the racial divide in this country at its starkest, ask people about how they remember Reagan. He gets no encomia from Black folks. We knew he was a throwback when he announced his candidacy for president in rural Philadelphia, Mississippi: where three civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney, were murdered in 1964. As SNCC veteran Dave Dennis recounts in Dave Dennis Jr.’s book The Movement Made Us: A Father, a Son, and the Legacy of a Freedom Ride, in the recovery effort for their bodies, a whole graveyard of murdered Black folks were brought up from the water. That was where Reagan began.

And so country ways were necessary, even unconsciously. An important note to make: Country and Southern are not the same, but there’s a lot of overlap. Country is more than region, it is found in disposition. It is earnest and it is honest about the body and feeling. An analogy might help: Country is to Southern as rusty is to ashy, rusty as in “sharp as a tack, rusty as a nail, ain’t took a bath since Columbus sail.” (That’s an old one. Lest you forget, we’ve been rhyming couplets and stanzas for at least a century in the Black South.) It’s the rougher side of truth.

The country idiom of hip-hop was there since the beginning and remained a minor note, perhaps a grace note, for a long while. You can see it if you search hip-hop lyrics websites for words like collard greens, granddaddy, big mama, cuss, coming out of the mouths of people from New York and Los Angeles. And also in the blues inheritances—twelve bars extended to sixteen in which a tragic story with a hero’s transcendence is a cathartic message. As much as jazz critic and novelist Albert Murray dismissed hip-hop, he could have been describing it when he said of the blues: “It’s an attitude of affirmation in the face of difficulty, of improvisation in the face of challenge. It means you acknowledge that life is a low-down dirty shame yet confront the fact with perseverance, with humor, and above all, with elegance.” Despite the decrying of elders, there was nothing new to the wild stories of bad men breaking all the rules, meeting hard luck, and winning anyway.

That said, something changed in 1995 at the Source Awards when the Atlanta duo OutKast won the award for New Artist of the Year (group). The crowd booed. And André 3000 said the phrase that reverberated around the industry: “The South got something to say.” Within five years the South was at the very center of hip-hop, and so were unapologetically country ways.

There had been Southern hip-hop since the beginning. And some, like Scarface out of Houston who—through collaborations with Kool G Rap, an icon of East Coast hip-hop, and Ice Cube of the West—gained mainstream hip-hop recognition along with his group the Geto Boys by the early 1990s. However, outside the South, our hip-hop was mostly mocked, though sometimes imitated. With its percussiveness, drawls, and bacchanalia, it was seen as less lyrical and less serious. Yet, here was OutKast, a lyrically masterful wholly ATL “Jawja” group, taking center stage.

But it wasn’t just them who shifted things. A lot changed between 1995 and 2000. The deaths of Tupac in 1996 and Biggie in 1997 seemed to be the terrible conclusion to regional bigotries. Snoop Dogg’s Calibama cadence (you could hear his parents’ Mississippi mouths coming out of him) had primed a public for Southern sounds. And the public had expanded. Hip-hop had become incredibly lucrative, and capitalism thrives on the constant cycle of new products. Looking South made sense.

That doesn’t tell us why the core Black youth audience of hip-hop listeners who validated music and drove the attention of the much larger public arena wanted that sound—brown liquor soaked, church inflected, and yet young, streetwise, rich with the language play of today—a sound that captured the present without leaving behind the past. Tragedy, I think, tells part of the why and the way back home. Bill Clinton’s welfare reform bill passed in 1996, immediately throwing poor people into extreme poverty. Again, a period seen as a triumph for the nation was devastating to Black communities. Rates of incarceration in the United States grew by 47% in the 1990s. As Wall Street boomed, so did crack. Y2K fears (everybody was afraid the grid would fail and we would be cast into chaos) led to a constant buzzing anxiety. As people do, they returned to the root.

The mistaken assumption made with migration and immigration is that the place from whence you came remains the same. But every place changes. I promise you this, as someone who has been coming and going from the Ensley neighborhood in Birmingham my whole life, more often gone than present, that even with what Amiri Baraka called the “changing same” evident in the resilient architecture and the reliability of that refrain “mhmm” said round robin, the changes are remarkable. There are loft apartments now, and a hotel on the West Side, and sushi spots. Still, places with unbroken relations to the ancestral land and language have what we might call grammars of the past readily available. All of the ways of doing can be remembered and therefore remixed.

In the beginning of the twenty-first century, the particularities of various country ways and Southern spaces gained huge popularity in hip-hop. There were the Tidewater and Hampton Roads sounds of Pharrell Williams, Missy Elliott, and Timbaland and Magoo. The rolling New Orleans tongues of Master P, the Hot Boy$, and the Big Tymers, and later iterations with Young Money and bounce. Other subgenres like the chopped and screwed style DJ Screw gave to Houston, and crunk, out of Memphis. Southern geographies—the car culture of Houston, the Atlanta strip club alongside the Asheville-born, Atlanta-made innovations of Jermaine Dupri—made us question where exactly the Black metropolis actually was when the gutbucket places were so appealing. The South was called “the dirty,” appropriate for the proximity to both the soil and funkiness.

Nelly called what was happening by its name with his debut album Country Grammar in 2000. It catapulted him to stardom. Nelly was crisp, clean cut, always smiling, St. Louis-by-way-of-Texas-country, looking just like a football player from a small-town high school. No ice grilling was necessary even with diamond glistening fronts.

When Nelly received the BET I Am Hip Hop Award in 2021, he gave a heartfelt speech, recalling his loneliness in the music world. “Just to be clear,” he said, “I never had a co-sign. Nobody stood on stage and put their arm around me. Nobody put a chain around my neck. I got thrown in the deep end and was told to swim.”

That vulnerability is the country idiom. Even when drawling rappers took the limelight, they carried an ever-present awareness of being seen as less-sophisticated, and therefore, less-than. And that’s a necessary story to pass on.

Because being country is also keeping a sense of your value in the face of diminishment. How else did they survive sharecropping, Jim Crow, and lynching? How else did the people living under the thumb of the planter class change the world from the underside, twice? First in the Civil War and second in the civil rights revolution.

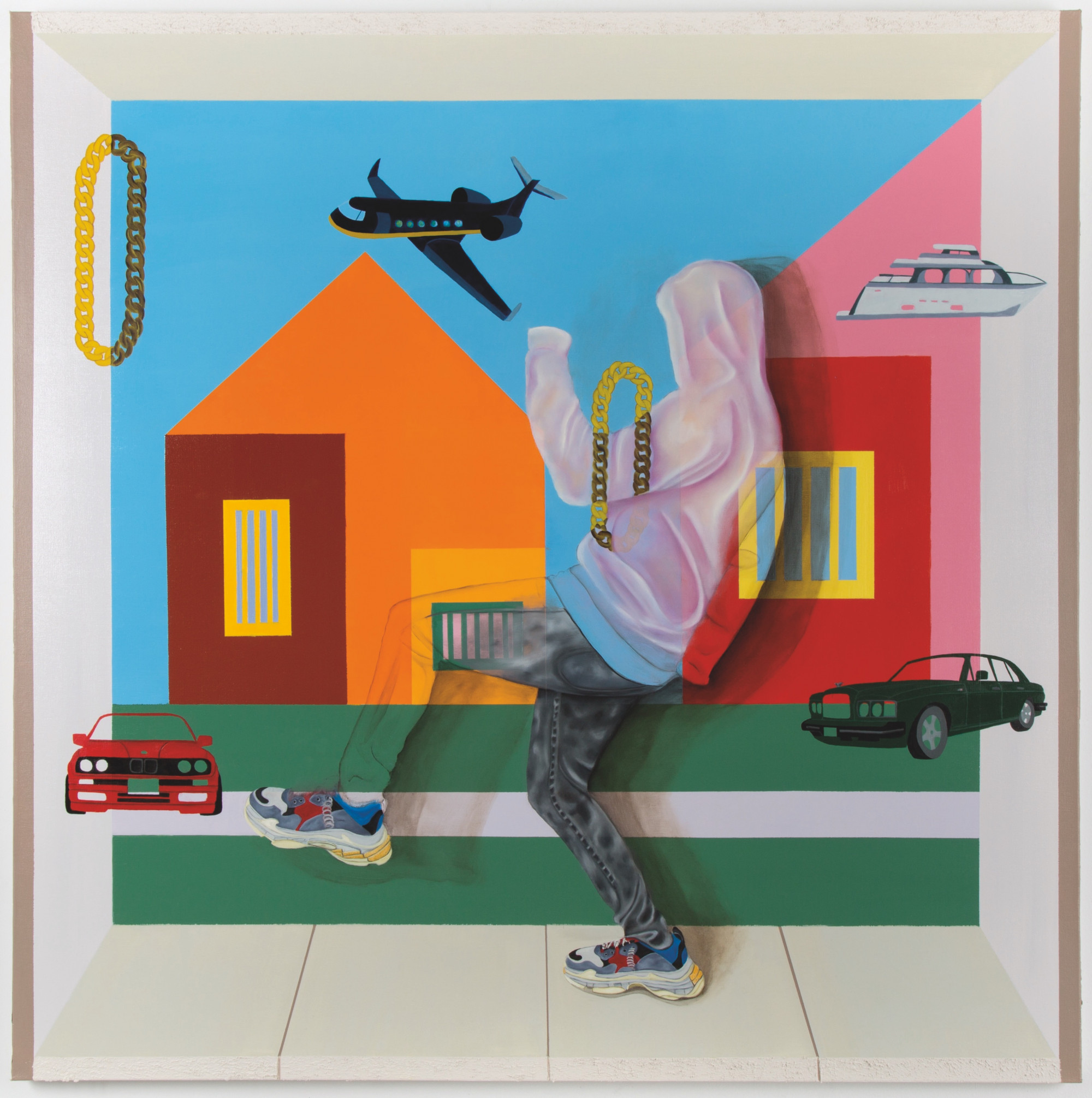

Hood Dreams, 2019, oil paint, drywall on canvas (48” x 48”), by Jamaal Peterman © The artist. Courtesy Vigo Gallery, London

An old head now, I listen to music of twenty to forty years ago more often than new songs, although I find myself especially taken with the country voices of a new crop of women rappers like Megan Thee Stallion and Latto who challenge the masculinist pose that dominates hip-hop just like it did with the toasts before it. Like the blueswomen who adorned themselves in sparkling finery and boasted of their own prowess, these lyrical daughters of Ma Rainey and Ida Cox are reminding people that organic feminism is a country thing, too.

And when I’m feeling vulnerable myself, I listen to Big K.R.I.T.’s 2014 “Mt. Olympus” on repeat. It was K.R.I.T.’s response to what we might term the dawning age of Kendrick Lamar, specifically his verse on Big Sean’s 2013 track “Control,” in which Kendrick dissed major names in the industry. Before the Pulitzer and all the Grammys, K-Dot had been crowned the greatest. And K.R.I.T. was supposed to be flattered to be mentioned. As the lyrics unfold, he makes clear he isn’t flattered at all. Because the status of the industry isn’t his own.

His distrust is earned. “You tellin me I can be king of hip-hop when they wouldn’t give it to Andre 3000, Nigga please…” The industry isn’t where he experiences his affirmation but rather with his folk: “You ain’t sell out a show until you sell out one in Mississippi.” That is ethos and testimony. K.R.I.T.’s assertion that “What’s good for hip-hop may not be good for my soul” is not a new formulation. Black musicians have long found themselves vexed when an organic form of music is celebrated by the recording industry. There is a cost to institutionalization and mainstream recognition. In K.R.I.T., I hear an echo of the musicians who disavowed the word “jazz” once it had become a gatekeeping term for critics and scholars of what is known as America’s classical music, in favor of “Black American music.” After all, what mattered most is that it came from the people.

Once upon a time, the finest bluesmen came out of Parchman state penitentiary. Covered in funk, long-abused, familiar with the hot sun and high cotton, they served as America’s blue note, that unstable, worrying position in a composition that is indispensable to American sound. With all its anguish—more and more rappers locked up and shot down, swimming in depression and addiction—hip-hop is a country blues blue note to our world today. I recommend you listen.