The Tragic Tale of Rackback Tom and His Repentant Spouse

A ballad

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

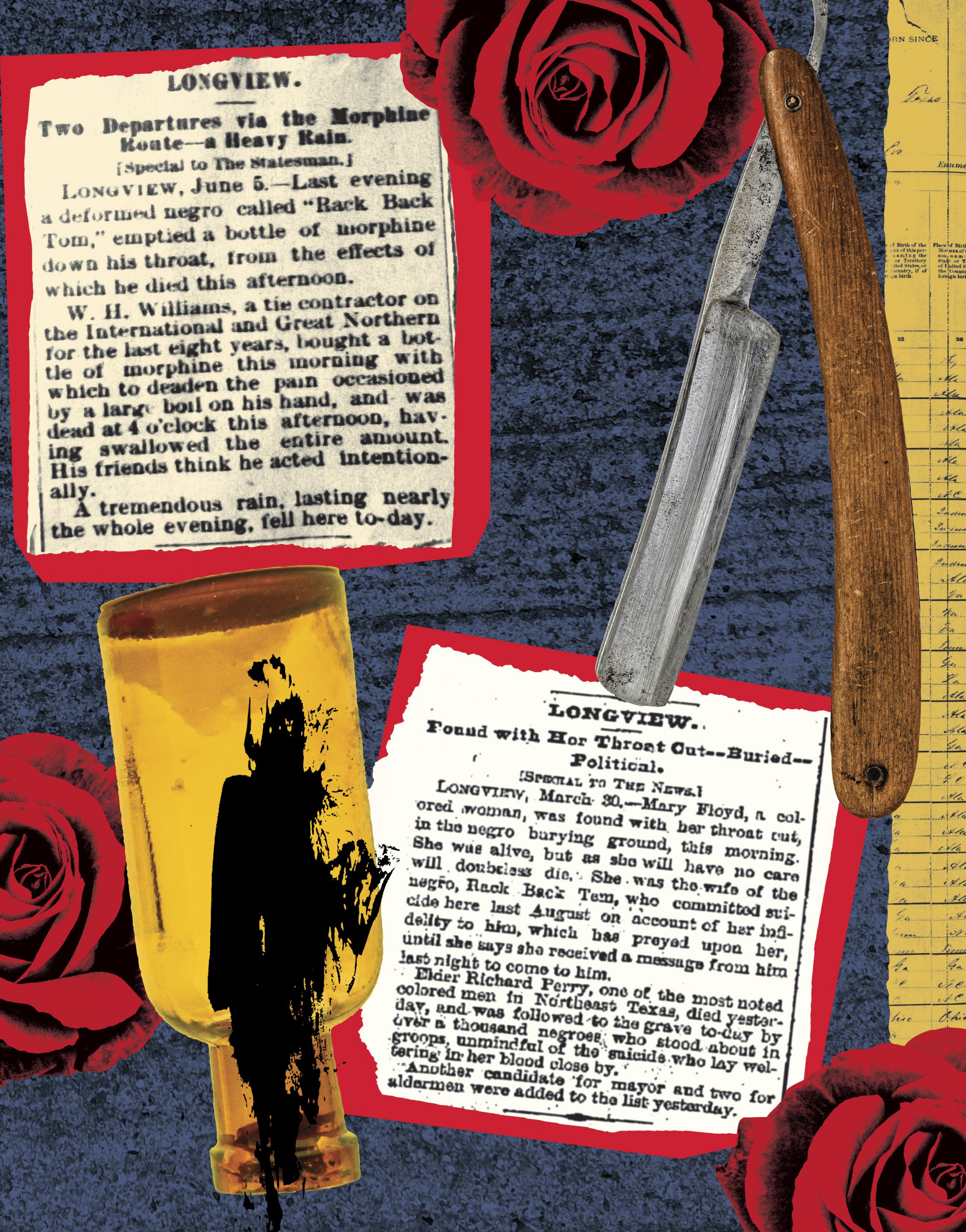

Illustration by Carter/Reddy. Source Photos © Adobe Stock. Razor: Vlad Ivantcov; Bottle: Walter Cicchetti; Roses: alesikka

The world of the word-searchable online databases of old-newspaper archives can be an eerie place—both a consoler and an extender of insomnia. The searcher moves down hallways full of blue ghosts who play out human destinies, who are always flickering into a kind of early-cinematic life. You witness things. That famous scene in Blade Runner, when Rutger Hauer is talking in the rain, remembering spaceships on fire? You feel like that sometimes. People ask what you’ve been doing, and you say, “Research.” Occasionally, you come across something you can’t just shuffle into a folder called “Amazing leads for down the road” or whatever. You can hear it crying out that it wants to be known.

Such is the story of Rackback Tom and Mattie Floyd, which has its whole existence in a smattering of documents and news items from East Texas in the 1870s and ’80s. I encountered it in the fourth column of the third page of the Austin American-Statesman of June 6, 1883. I don’t precisely remember the path of keywords and search-terms that led me there, but I know that I had become interested in the town of Longview, Texas, about forty-five miles from the Louisiana border, because of an extraordinary hanging that had occurred there five years prior, in 1878. Actually, the hanging was probably the opposite of extraordinary. A Black man named Diomed Powell, from Fannin County, and a mixed-race man from Nashville, Tennessee, by the name of Ben Hadley, had been convicted of murdering a local German grocer and were about to be executed. Both had confessed to involvement. They had bludgeoned him and cut his throat with a cheese knife. What’s extraordinary is how the talk in their cells, before they were led to the gallows, got recorded down to the word by some unusually intrepid and meticulous reporter. It’s rare to be able to hear, especially at that level of accuracy, across a hundred and fifty years. A Baptist preacher was present, a Rev. Mr. Booth. The prisoner Hadley started making speeches, asking the reporter to take down a “Letter to the Boys,” which he had composed. It was full of bluster. “If it could not be done without blood spilt, we feared no man or anything.” The Rev. Mr. Booth did not like it. He had been in charge of the men’s souls during the preceding days, and now he felt publicly embarrassed by this display of hard-heartedness. He “kneeled down suddenly near the door of Ben’s cage.” He said, “Ben, you have shown in your statement a spirit of vengeance and viciousness that proves you have not profited by my prayers.”

Ben —Mr. Booth, I have nothing to say ’bout it. I say all them things to the world; they are not my feelings.

Mr. Booth (with some excitement) —You can’t with my sanction send out such statements as your feelings. There is no hope for you now.

Ben —I think there is hope, Mr. Booth.

Mr. Booth —No, no; there is no penitence; you justify your crime.

Ben —Sorry you think that way, Mr. Booth.

Mr. Booth —No, sir; you will go from the gallows to hell.

Ben —Don’t say that. I have been trying to get shut of this confession a long time. I hope God will hear your prayer.

Mr. Booth —My prayers avail not for such a spirit as yours.

Ben —When I came to Texas there was the worst mob law in the world here. Got we boys started and—

Mr. Booth —I am imploring you, as your friend and minister, to turn while yet—

Ben —If I had not listened to your prayers so solid for me I would have killed myself in here, and they would not have the pleasure to hang me.

Mr. Booth —It is loss of time to pray for a hardened man, who wants vengeance for his race.

Ben —When the world was discovered; but I am sorry to hear you talk that way, Mr. Booth.

"When the world was discovered”—those are the little bits of language that don’t get preserved. The strange things we say.

That all got me interested in Longview, and I spent a couple of hours hunting for other early mentions of the town. Established just after the Civil War, it was a fantastically violent place during its first two decades of existence, especially when you consider the tiny population. Somebody was always blowing somebody’s brains out with a Derringer over a petty slight. A relatively innocent sentence from the winter of 1885 does work that a long list of gruesome examples could only attempt: The skating rink opens up, and the management finds it “needful to prohibit tripping and fast skating, to prevent rows and murders.”

In the year 1883, two things were happening in Longview. The racial tension, never absent, suddenly flamed up. The reasons aren’t clear. There had been an incident at the start of the year. A group of Black men had “attempted to rescue two negro prisoners in charge of a white officer.” Despite the fact that there was a whole “gang of negroes,” three of them were killed, but only one white man (strange how often it happened that way). This event may have caused unrest in the town. Later that year, the papers reported that the whites of Longview were living in fear of “a murderous outbreak of the negroes” and standing guard day and night. Soon a “reign of terror prevailed in every portion of the country around Longview.” The white farmers started keeping their wives and children in the gin houses for safety. Hundreds of men were “buying ammunition and Winchesters.” There were, moreover, “indications that as much fear has been excited among the negroes as among the whites.” An anonymous correspondent added, whether with tragic irony or cold-blooded mockery, it’s hard to tell, “We are inclined to think the fatalities will be found mostly on the negro side.”

The other thing happening in Longview during that same time was a minor suicide epidemic. Donald Carter, a prominent citizen, “suicided by taking morphine.” His young wife had died, one of “the most charming young ladies in Texas.” Brooding over the loss, he “finally determined on self-destruction.” J. W. Cheatham, on trial for insurance fraud, “obtained permission of the officer guarding him to go to the jurors’ room in the courthouse to rest, and when in the room he by the aid of a small piece of looking-glass cut a deep gash in his head back of the ear, laid down and bled to death.” At one point, there was an outbreak, three suicides in one week. It’s in the reporting on that little cluster of deaths that Rackback Tom makes his first appearance. The first article is a dark, lost American poem. It even has a kind of sonnet form.

LONGVIEW.

Two Departures via the Morphine Route—a Heavy Rain.

[Special to the Statesman.]

Last evening a deformed negro called “Rack Back Tom,” emptied a bottle of morphine down his throat, from the effects of which he died this afternoon.

W. H. Williams, a tie contractor on the International and Great Northern for the last eight years, bought a bottle of morphine this morning with which to deaden the pain occasioned by a large boil on his hand, and was dead at 4 o’clock this afternoon, having swallowed the entire amount. His friends think he acted intentionally.

A tremendous rain, lasting nearly the whole evening, fell here to-day.

The last part: a quietly sublime American sentence. Rackback: probably scoliosis. Nine months later, this time in the Galveston News of March 31, 1884. Galveston is almost one hundred miles south of Longview—the story was being picked up by other Texas papers, a piece of colorful melodrama from a small town:

LONGVIEW.

Found with Her Throat Cut—Buried—Political.

[Special to the News]

Mary Floyd, a colored woman, was found with her throat cut, in tho [sic] negro burying ground, this morning. She was alive, but as she will have no care will doubtless die. She was the wife of the negro, Rack Back Tom, who committed suicide here last August on account of her infidelity to him, which has preyed upon her, until she says she received a message from him last night to come to him.

Elder Richard Perry, one of the most noted colored men in Northeast Texas, died yesterday, and was followed to tha [sic] grave to-day by over a thousand negroes, who stood about in groups, unmindful of the suicide, who lay weltering in her blood close by.

Another candidate for mayor and two for aldermen were added to the list yesterday.

The “negro burying ground.” That’s probably the Union Post Oak Cemetery, about ten miles outside of town, in what the very helpful Longview Director of Grant and Human Services, Laura Hill, described as a “historically more black portion of the county.” Elder Perry was the founding preacher of Bethel Baptist Church in Longview. The church still exists. Notice that the article has the same three-part structure, two paragraphs of profundity and one of mundanity. Who was writing them? Someone worked as a “special correspondent” to a larger network of Texas papers. The only person I could find identified as a journalist in Longview during these years was a white man named Harry Woods, from Altoona, Pennsylvania. He was said to be “employed on a paper called the Longview Democrat.” He sent a copy of the Democrat back home to his friends.

One thing: “as she will have no care.” I think that means that she is refusing care. But it could mean that they do not intend to provide it.

Variant versions of the article include different (though never contradictory) details. It seems that Harry Woods, if that’s who’s writing these, was fattening his paycheck (only slightly, no doubt) by sending different copy to different newspapers for which he served as Longview correspondent. An item appeared in the Fort Worth Daily Gazette.

LONGVIEW.

Death of Elder Perry—The Tragic Tale of Rack-back Tom and his Repentant Spouse.

Special to the Gazette.

One of the most noted negroes of Northwest [sic] Texas, Richard Perry, died yesterday. At least 1,500 colored people were present at his burial.

Last August a colored man, Rack-back Tom, committed suicide because of his wife’s unfaithfulness. This seems to have partially crazed her, and this morning she was found near his grave with her throat cut. She was not quite dead, but said Tom had sent for her and she was going to him. Of all the multitude in attendance at the burial for Elder Perry, none heeded the half-crazed dying suicide.

One candidate for mayor and two for aldermen were added to the number yesterday.

Another version, this time from the Dallas Daily Herald, gives still more color.

LONGVIEW.

Mattie Floyd (colored) attempted to cut her throat with a razor yesterday. Her husband died about a year ago, and as she says appeared to her Friday, told her he wanted her to come to him to cook for him and wash him a shirt. Saturday she cut her clothing to shreds, broke up the furniture and with a razor on Sunday morning inflicted two gashes in her throat from which she may die, falling over her husband’s grave.

Here her name—Mary, in the first piece—has become Mattie. The latter turns out to be correct. She and Tom are there in the 1880 census for Gregg County, Texas. Thomas and Mattie Floyd. He’s a laborer, she’s keeping house. He’s twenty-one, she’s twenty. Neither of them can read or write. Their marriage certificate, from 1878, also exists. They were married by the justice of the peace. That document gives her maiden name: Martha Sapps. Thomas Floyd married Martha Sapps.

Tom’s 1883 suicide attempt was successful, but in 1884 Mattie’s failed. We know because a year after it, in July 1885, she was charged with attempted murder and convicted. Here’s another special dispatch from Longview, in the Dallas Herald. Seems to be the same person writing.

LONGVIEW.

Mrs. Mattie Floyd, colored, plead guilty of an attempt to murder Cary Post and was given two years in the penitentiary. It will be remembered Mattie was the wife of “Rack Back Tom,” who committed suicide a year ago, and Mattie procured a razor and went to the grave of her departed husband and cut her throat, but survived. She stated that she had promised Tom to meet him in hell the next morning.

I couldn’t find out anything much on Cary (or more properly, Carrie) Post—except that a white woman by that name did live in Longview—nor about what had happened that Mattie tried to kill her, or if that accusation was even true. What’s clear is that Mattie is there in the Texas prison records for 1885. In the “Convict Record” book for the newly constructed Rusk Penitentiary in Cherokee County (built to relieve overcrowding at Huntsville) she’s listed as Mat Floyd. That must have been her nickname. She was small: four-foot-six and 118 pounds. Her complexion is on the lighter end (“Mulatto”). Her habits (there was a column for “Habits”) were “Int.,” i.e., intemperate. She worked as a cook. The “Conduct Register” for Rusk Prison records that on at least one occasion she was punished for “Abandoning work.”

She got out in 1887. I lose her after that. A handful of Mattie Floyds and Mattie Sappses surface later in different parts of Texas. One got into trouble with the law, one was murdered herself, one married another man and had a bunch of children, and she lived to be old. None has a better claim than the others to being the same Mat Floyd.

Part of what makes the story of Mat and Tom disturbing is the racialized context in which we experience it, namely, white Southern newspapers of the 1880s. These accounts are not sympathetic, or not sympathetic enough. There is a leering quality to the language, and in reading them, one has at times a sensation like complicity. Stories like this were printed, in too many cases, to make white people feel better about their own lives, or to elicit head-shaking and laughter. As readers, we become another person at the funeral, refusing to pay attention to Mattie as she lies there, or worse, maybe, trying to pay attention but finding that she will receive no care. The suffering, hers and Tom’s, has a nobility and a terror that are independent of us and beyond us. If we were to do away with these compromised, unfriendly sources, the couple would not come into sharper focus, they would disappear. Should they be allowed to do so? It seems unacceptable.