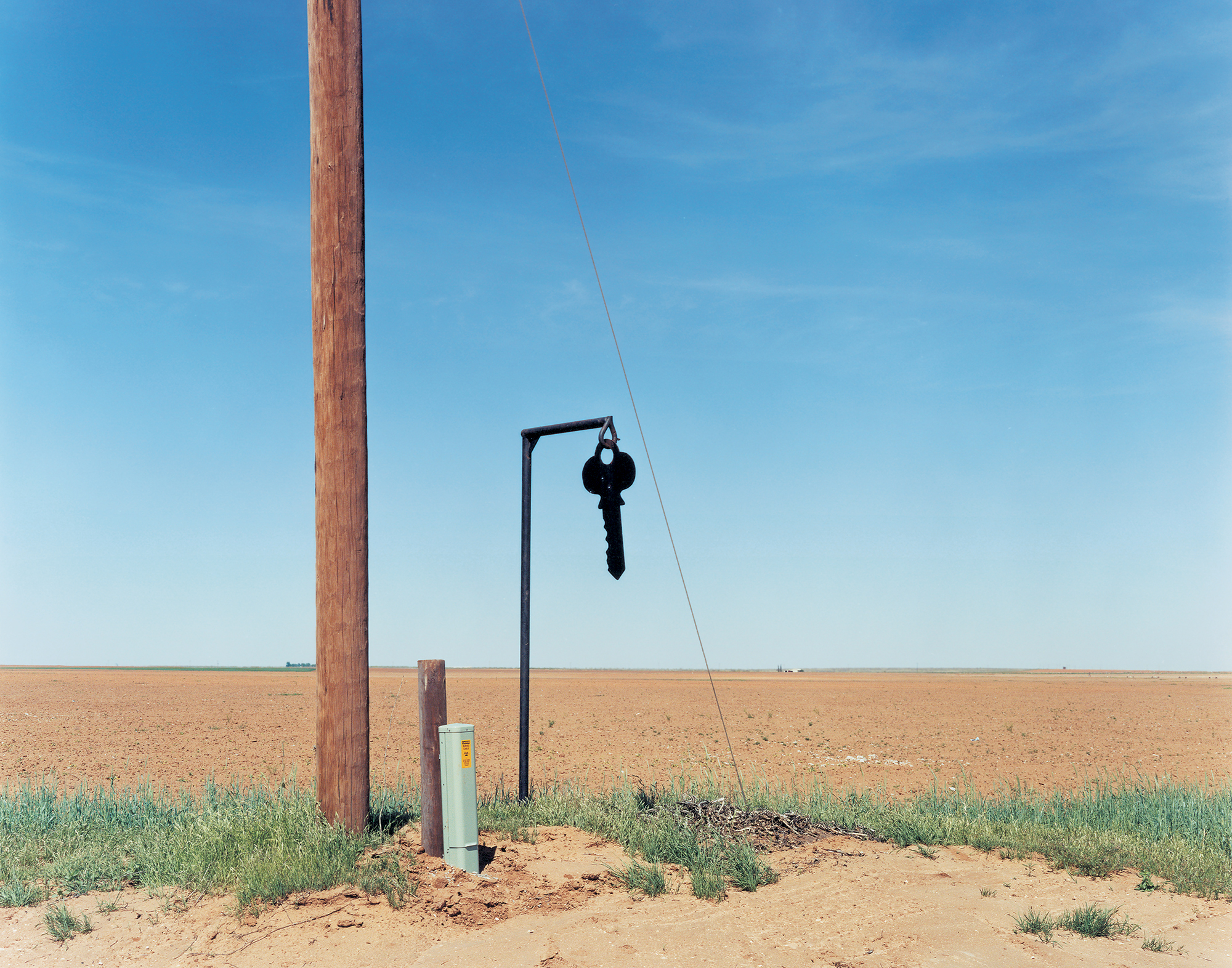

Black Key, Tarzan, Texas, 2002, photograph by Peter Brown. Courtesy the artist and PDNB Gallery, Dallas

Five Hours from Someplace Beautiful

By Brendan Egan

GRAY FOX

(UROCYON CINEREOARGENTEUS)

One early morning, a few months after my daughter was born, I ducked out to my backyard to turn on the sprinkler and found a gray fox balancing on our wood fence. As agile as any house cat, it prowled the fence top, maybe thirsty for the wading pool that had previously slumped in the shade of our desert willow. I threw the door behind me closed—an instinct—and the fox paused to look me in the eye. It stood straight and still, its flared, black-streaked tail raised like a flag.

I’d heard the hoarse yelp of a fox once before: sunset, walking the dirt easement that extended beyond the end of the road behind our subdivision. It was total shit land out there. A chunk of it was irrigated for grazing a herd of maybe a dozen cattle, there were high tension powerlines, a submerged gas pipeline, and some lots slated to be fracked and drilled, but mostly it was mesquite, bunchgrass, and plastic bags.

In that feral space, the sound of a wild animal had felt fitting, but perched on my fence, the fox became an uncanny reminder of the fragile claims we lay on the land we occupy.

BARN OWL

(TYTO ALBA)

Everyone in Midland knows something beautiful is just a five-hour drive away. Bumper stickers from the Texas Hill Country, Big Bend National Park, Carlsbad Caverns, and the mountains of New Mexico and Colorado tattoo our pickups and SUVs. But the lights on the local prospect are somewhat dimmer. In a community built upon extraction, the value of its land is foremost a calculation of the barrels it can provide. Aesthetic pleasures lie elsewhere.

Promotional photos for the city often feature the downtown skyline rising above duck ponds and verdant slopes of golf courses—belying the truth of an environment that receives less than fifteen inches of precipitation in an average year. Yet, our very livelihood depends on expanses of space where so many of us spend our working days digging through dust.

Our home was built in 2014, following the height of the oil boom that drove a severe housing shortage. Workers poured into town, lured by lucrative jobs in the surrounding Permian Basin. Rents were higher in our city of about 130,000 people than in Dallas or Austin. Man camps, where temporary oilfield workers are housed, were full. Motels were full. RV parks were full. People were moving here and living in the cabs of their pick-up trucks while making thousands of dollars a week.

Housing developments like ours have popped up in waves along the verges of the city: an HOA, a community pool, a half dozen preset floorplans, your choice of brick façade. They’re raised in a rush by corporate builders, sprawling out into former ranchland from a once compact city center to fill the nagging demand for housing.

Like most of the new middle-class neighborhoods of Midland, ours half-heartedly aspires to the slick charm of the suburban American dreamscape. Our front yards are made of gray river rock or squares of sod that never quite take to the soil. Pumpjacks teeter in quarter-acre lots set between cul-de-sacs. There always seems to be not quite enough trees and a few more trucks than anyone could need.

Our builder told us to expect some wildlife to appear our first year—scared out of hiding by the scrape of bulldozers and graders. We found scorpions on the bathroom tile. Our neighbors were freaked by a rattler curled into the corner of their garage. One afternoon, my wife spotted a barn owl roosting in the just-framed eaves of a two-story across the street. It felt as if the moon itself had been displaced. We stood at the bottom of the driveway, watching until it yawned its broad wings and circled toward the seemingly empty fields that lay beyond the subdivision.

The next Saturday morning, I went walking in the direction of the owl, past construction sites where roofers and masons were already blasting corridos from their boomboxes. I was looking for some sense of place—an assurance, however vague, that my life is connected to the natural world and the history of the people in it. I had an impression that neighborhoods like ours are not place itself, but a palimpsest upon it.

To find the here here, I had to walk past the end of the road.

TUMBLEWEED

(SALSOLA TRAGUS)

Following the owl beyond the subdivision, on the first of many walks, I found myself in an ill-defined space: ugly, post-agricultural, metamorphic. Not the oilfield proper, and not exactly town—not yet, anyway. A catchment basin, a transformer station, then a patch of about two square miles of scrub.

British environmentalist Marion Shoard coined the term “edgelands” to describe “the latest version of the interfacial rim that has always separated settlements from the countryside.” Her edgelands seem to be places of neglect—where the guiding hand of the planner has vacated the premises, leaving battered nature and the people who move through it to their own devices. But here, where hunger for land and its resources is bottomless, any such edge is one that only pushes ever outward.

This territory I’ve come to love deserves a more honest name: shit land. Abused but resilient, transformed but still wild. You can find it everywhere in America, and it deserves our consideration.

In West Texas, this is where the plastic shopping sack becomes unlikely kin to the tumbleweed and the dragonfly—each animated by a similar wandering spirit. Everything is steered by the wind across our half desert, and these three are driven—however circuitously—toward the points of yucca, barbed wire, and mesquite.

On that first walk, I saw each of them congregating along a fence that ran parallel with the roadway. A few days before, a Haboob, a huge rolling dust storm, brought brown skies and left grit between my teeth. It’d also knocked loose stampedes of tumbleweeds. They’re an icon of the west, but their introduction to the United States can be drawn to contaminated shipments of Russian flax to South Dakota in the 1870s. Spread by railway and wind, they quickly became emblematic of frontier solitude. They’re hawked as rustic tchotchkes on Etsy.

The shrubs grow three feet tall through the summer, covered in fleshy green needles. As autumn approaches, green tinges red and the needles curl up from the dirt in thick mats, revealing hundreds of thousands of seeds the parent plant will broadcast as it dies, breaks away, and rolls across the plain.

As the morning began to warm, I found dragonflies resting in the sun on strands of barbed wire. The green darner—large, lime and electric blue—makes a multigenerational migration of up to nine hundred miles, from Mexico to Canada. Though the patterns of their seasonal movements are not well understood, it’s believed that they are able to read the prevailing winds of a given day and lift themselves into currents that point them toward their seasonal destinations.

The same fence that harbored darners and tumbleweeds also collected plastic bags. Blown from parking lots and truck beds and hooked on the fence points, they tattered in the breeze like Tibetan prayer flags, broadcasting over the land the sutras of our twinned local deities: commerce and petroleum.

HONEY MESQUITE

(PROSOPIS GLANDULOSA)

Alternately rutted and flattened by a procession of frack sand haulers and bulldozers, the lane of parched red and yellow silt where I walked for the better part of the last decade cut through dilapidated pasture. Neon airplane bottles of 99 schnapps were crunched into the ground from where they’d been tossed out the window of one of the countless white company pickups—whether in celebration or to ease the way through another shift was impossible to tell. Styrofoam confetti and bridal trains of bubble wrap littered the way toward a cattle guard on the horizon.

Walking one afternoon in early autumn beneath the buzz of the powerlines, I spotted a pair of Harris’s hawks hunting together—one swooping into the brush while the other waited on a rung of the powerline tower for whatever prey might be flushed into the breaks. Black-tailed jackrabbits—long ears pricked, testing the air—stood on their hind legs before bounding ten or more feet at a leap, toward a ridge of mesquite that ran along one side of the road.

This was a windbreak, or the remains of one, planted to protect livestock and their feed from desiccating winds. Only a few decades ago, much of Midland County was devoted to cattle, but the pressure of the oil industry has left only remnants of ranching today.

Honey mesquite—a tangled shrub of thorns, feathery leaves, and slender bean pods—is the most conspicuous presence in our southern stretch of the Llano Estacado—the tableland that tilts up 250 miles from here to the border of Oklahoma. Prior to colonial settlement, mesquite was at home in canyons and draws—sloping courses of ephemeral streams—and its smoky-sweet beans were prized forage for the Comanche and Apache. But eradication of controls on its growth (the millions of bison killed to thwart native peoples, shortgrass species grazed bare) led to its invasive spread throughout former prairie. A bane to cattlemen, its deep roots sucked up precious moisture, and the pods sickened animals. The marketing genius that eventually turned a nuisance into potato chip flavoring didn’t start until the 1950s.

Where it has been irrigated, mesquite can grow into small trees, collecting dunes at their feet. Their shade creates a niche for smaller shrubs, flowers, and vines like the buffalo gourd, whose triangular foliage and golden, baseball-sized fruits snake down through the jumble. It, too, has been naturalized here. A “camp follower,” it likely migrated north in the wake of migrations ten thousand years ago.

Legacy upon legacy, the human hand has shaped this land to meet human needs, and wildness has fitted itself accordingly. I watched the mesquite where the Harris’s hawks made their nest. In the hump of dirt and underbrush beneath, the jackrabbits hid from the hawks and from me.

SILVERLEAF NIGHTSHADE

(SOLANUM ELAEAGNIFOLIUM)

Like the mesquite and buffalo gourd, many of the plants I’ve encountered on my walks are best classified as ruderal—those species that, by dint of their prolificacy, speedy growth, and meager needs, are capable of pioneering disturbed soils. But it’s in the spirit of shit land to call them by their common name: weeds.

Silverleaf nightshade is my favorite.

Late spring through autumn, its dry fingers of foliage prop up five-pointed purple blooms, no larger than a nickel, spiked with vibrant yellow stamens. Late season, the flowers give way to fruits that could be mistaken for their agriculturally engineered cousins—yellow grape tomatoes. But such a mistake could be fatal. The whole plant is toxic, and livestock learn to avoid it, leading to its proliferation in overgrazed areas like this.

Still, even Guy B. Kyser, weed eradication expert at the University of California, Davis, admits to its “sinister charm.” It is admirably stubborn. Armored in hairy spines, with long roots and a vanishing need for water, it is nearly impossible to clear without pesticides.

It’s a gift to find reverence for the small and the common. Even in the driest summers, when the oversweet stink of Roundup drifted on the wind, sprinklings of purple lined the churned margins of the dirt roadway and sprang from cracks in the sunbeaten clay. Up close, I’ve noticed the translucent green hump of a tortoise beetle nudging its way down a leaf. Once, I was lucky enough to see at sunset: sphinx moths riddling between the blossoms.

COUCH’S SPADEFOOT

(SCAPHIOPUS COUCHI)

Any dry place is colored by long desire. The annual dozen or so inches of relief that fall in Midland seem to come all at once. Some summer afternoon, I was nearly seduced into staying out watching mammatus clouds, full as flesh pressed against fishnet, build into towering anvils. But I thought better of it and retreated home to listen to the pelting rain and hail.

In the days after, the ground let loose something resembling conventional beauty.

The pencil stems of zephyr lilies poked up from the sand, opening into wax-white stars seemingly only hours after the rain. Pale bells of yucca flowers, dangling from their spires, dripped nectar that drew ants and the specialist moths evolved to pollinate them. Tiny explosions of violet Tahoka daisies, Spanish gold, and scarlet blanket flower erupted in patches that drew butterflies—papery sulphurs and tiny blues decorated like Persian miniatures. Ornate box turtles emerged from the brush to sip from short-lived puddles.

This abundance was almost enough to obscure waterlogged curls of carpeting scraps or the sopping mattress dumped in the bar ditch.

Along one stretch of my dirt road, the subterranean course of the gas pipeline is outlined by yellow pickets warning against digging, but all around them, another kind of delayed satisfaction emerged with the rain: spadefoot toads unburying themselves from months of torpor. Herpetologists believe that they’re awakened not by moisture, but by the rumbling of thunder and precipitation striking the ground. In a few damp days (or even hours), they eat, find a tadpole-suitable source of water, mate, and—using toughened spurs on their rear feet—reburrow themselves.

Their pools must last ten days for spadefoot offspring to develop. A challenge, given that sporadic storms are often followed by air-fryer heat. Playa wetlands—natural depressions in which rain collects to form ephemeral ponds—are vanishing across the southern plains as they fill with sediment from upland erosion or are simply evaporated by an increasingly hotter, drier climate.

However, on the outskirts of housing developments, catchment basins provide an alternative. Channeling water away from neighborhood streets, ours filled just long enough to provide adequate mating ground. On its slopes, dozens of spadefoot males creaked enticements into an evening scented by chocolate daisies just blooming.

DOGWEED, OR DAHLBERG DAISY

(THYMOPHYLLA TENUILOBA)

In evaluating ecological aesthetics, we often reduce judgments to dichotomies—of ugliness and beauty, natural and unnatural—drawn from notions of purity. Canadian philosopher Alexis Shotwell identifies such distinctions as a legacy of colonialism. In describing contemporary appeals to the purity of the individual, she illustrates the absurdity of drawing the boundaries of our personal responsibility at the surface of our skin: “[Purity] means you don’t have to feel bad about other people getting sick and dying because they’re living downstream from a factory. They should’ve done something about that, they should’ve eaten more antioxidants.”

Shit land, sitting as it does between developed and undeveloped territory, shows the absurdity of drawing such boundaries in the environment. In contaminated space, perceived ugliness, and therefore reduced ecological value, stem from impure status.

The tactics of environmentalism have conventionally been driven by two moves: to restore and to preserve. Land perceived as wounded is bandaged and nursed back to a healthy, ostensibly natural state, while land perceived as worthy of protection is demarcated as if placed beneath a glass cloche. But in increasingly unavoidable and obvious ways, these moves feel futile, even counterproductive, facing the challenges of our late-petrocene period.

Most patently, the boundless effects of climate change reduce any protective dome to gesture. This spring, the Rio Grande stopped flowing through swaths of its course in Big Bend National Park two hundred miles south of here. Meanwhile, to our west, New Mexico’s Lincoln National Forest has seen a decade of destructive lightning strike fires fueled by extreme drought.

But a brief walk through a plot of shit land makes the interconnectedness of the natural world and human activity irrefutable. This place won’t lie for us. And for that it should win our attention.

I knew from the start that there was an expiration date on my personal patch of shit land. Despite a couple of busts in the oil market, people haven’t left. Advancing frack technology encourages continued drilling for oil in town. All this time, the edges have continued to be eroded by apartment buildings, a gas station, a Wendy’s, more drilling, more subdivisions. The city paved the road and ripped up the windbreak where the jackrabbits hid. The foxes and owls are gone.

Soon, we’ll be gone, too. My wife and I are moving to a neighborhood closer to “Old Midland,” with canopies of street trees and a grassy public park.

It has often been remarked that West Texas smells like money. The dark, eggy scent of hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide hangs on the air, even miles away from pumpjacks lifting sour crude. But the smell that I will always associate with this place is from a tiny plant with delicate yellow blooms and leathery foliage, too easy to step on while you have your eyes on something else. Crushed underfoot, it has an odor that comes back to me in dreams: sometimes like lemons and parsley, sometimes like a headache. Some people call it Dahlberg daisy, others dogweed. I could grow some in our new backyard, but I know that I won’t. It doesn’t belong there anyway.