The Old-Time Sounds of Clifftop

By Julia Thomas

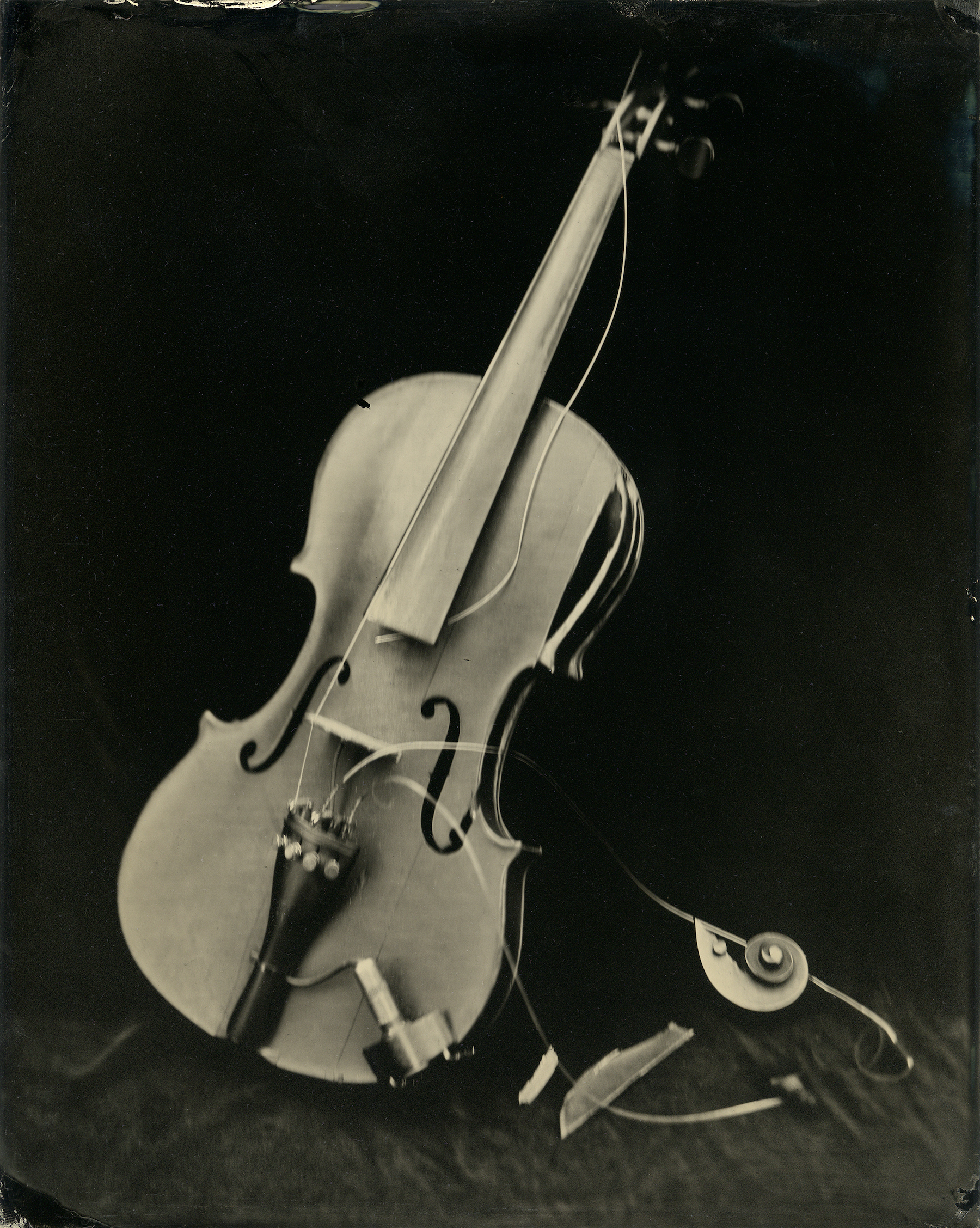

Cara's Broken Fiddle, a photograph by Lisa Elmaleh © The artist

I arrive in West Virginia on a Monday night, the first of August, after driving through Pennsylvania while a tornado warning lit up my phone. It’s two days before the official start date of Clifftop, or the Appalachian String Band Music Festival, and I’m with Jeff, a family friend who is more like an uncle, en route to the mountaintop gathering for the first time after dreaming about it for years. My dad, who grew up in the state but has long lived near Seattle, will join us once the festival is underway. Peering out the windshield, we keep looking toward the clouds for evidence of funnels, but they are invisible or else not in our path. Instead, we move through pockets of heavy rain that sprout in minutes-long summer stretches and dissipate as quickly as they appear, blooming through cracks in the still sky.

Jeff and I alternate between playing music and interviews in the car. We listen to Old Buck, a contemporary quartet string band; a conversation with Grammy-nominated fiddle player Bruce Molsky on Cameron DeWhitt’s old-time music podcast Get Up in the Cool; and a slew of Irish tunes. The drive is kind to us, long enough for several records, McDonald’s french fries, and winding chats about the days to come. We wonder aloud about how many people will attend the festival after a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic and what the mosaic of veteran Clifftop-goers and new players will look like.

As a very beginning fiddle player, I’m excited, suddenly spinning with possibility, to at last head into a corner of the world and a region of my father’s life I’ve heard so much about and have yet to truly experience. For him, the trip to Clifftop is a retracing of steps accompanied by newness. He grew up in Charleston but regularly traveled with family to visit his grandparents on their farm just miles from where the festival takes place, and hasn’t been back to this area of West Virginia in decades. Though a lifelong guitar player and songwriter, he is relatively new to the old-time genre.

As a kid, I’d hear him playing guitar distantly while I fell asleep. He was always a night owl, voice muffled and chords barely audible behind closed doors. In this way, too, it is a kind of homecoming for us; it is to my dad that I owe my enthusiasm for music, for digging back decades for songs and eventually finding my way to old-time.

Days later, huddled under a tent next to the festival’s performance stage on the brink of an afternoon downpour, we will wait for the rain to fall stronger, and a stage manager will laugh and comment that “it wouldn’t be a string band festival without a storm.”

There are hundreds of music festivals under the folk, bluegrass, and old-time umbrella across the U.S. and internationally. But within that landscape, Clifftop is beloved, legendary. At times, it has been the largest annual gathering of string band musicians in the world. Since 1990, the festival has brought together thousands of people from every U.S. state and at least twenty countries for five official (ten, if you count the pre-festival) days of immersion in playing old-time and string band music—though many attendees expand into other genres beyond the scope of Appalachian old-time traditions, bringing in styles with Cajun, Latin, Irish, Scottish, jazz, and other influences.

Old Clifftop Road passes alongside small farms, a horse pasture, and gas stations on the way to Camp Washington-Carver—which opened in 1942 and is now on the National Register of Historic Places—where Clifftop is held. The hilly road is winding and shadowed, the outlines of canopies dappled across it, leaves in the depths of deciduous green. Deer are frequent jaywalkers.

When we arrive, many people are already settled at the festival and have been for days. At the campground’s center, acting as obvious architectural anchoring points, are the Great Chestnut Lodge, a large wooden cabin with alternating brown and white panels made of Virginia Chestnut (the largest structure of its kind in the world), and the nearby stage, where the fiddle, banjo, traditional band, and neo-traditional band contests take place each day. But the soul of Clifftop lies in its campsites, or neighborhoods, and the people who’ve come from across the country and world to play for days on end. Multi-colored tents, motor homes, RVs, tarps and hammocks strung between tree trunks form a temporary, ramshackle patchwork within which time is suspended.

Clifftop is widely known among musicians and lovers of old-time far beyond Appalachia as a key learning ground for budding musicians to collaborate, compete in contests, and learn in real time from legendary players. Multiple young fiddlers express how the festivals are a chance for them to participate in this firsthand. Micah John, a sixteen-year-old from Boston who’s at her first Clifftop, tells me while we’re standing by the stage that “so many of her heroes” are playing in the open fiddle contest; she shows me a list on her phone where she’s keeping track of all the new tunes she learned at the festival.

Ryn Riley, a seventeen-year-old from Asheville, North Carolina, says that it’s inspiring to be surrounded by a range of amazing players, both younger and older, as well as a welcome challenge. “It really helps me grow. Because it’s like when you’re around that dynamic, you want to copy it, right? Kind of like learning a new language,” she says. “You have to speak that language.” Riley, embracing the enthusiasm shared by seemingly the majority of Clifftop campers, spends most nights playing until late, sometimes 4 or 5 A.M., when the sun begins to rise.

“It’s not just a festival,” Bruce Molsky tells me. He has been attending since the beginning and is a teacher to numerous players, including John and Riley. “It’s part of my musical history.”

T

he Appalachian String Band Music Festival was founded by a group of West Virginia-based old-time musicians who, in the late 1980s, saw a gap in the lineup of festivals that players of the genre often traveled between—as well as an opportunity to situate an old-time festival encompassing a wide range of influences in a more rural, picturesque environment. Camp Washington-Carver was, for a few years, the site of the Appalachian Open Championships, a bluegrass music contest, until its discontinuation by 1987. It became an obvious choice as its co-founders brainstormed: Will Carter, a lifelong West Virginian and string band musician, Bobby Taylor, a fourth-generation West Virginian fiddle player, and others sought to create a festival that aligned with the aspects they loved about other days-long conventions and offered participatory, meaningful experiences for players of old-time music more broadly.

In the early years, the festival coordinators began by inviting musicians in the area and those in their networks. Taylor, now Clifftop’s contest coordinator, estimates that about four hundred people were in attendance the first year but that steadily increased into the thousands (in 2015, Clifftop brought in close to five thousand people). In contrast, this past year saw approximately two thousand five hundred people visit the festival between the time of pre-camping through its end (attendees and organizers alike shared that they suspected a variety of factors were at work, with COVID-19 still being a major deterrent).

During my first afternoon at Clifftop, I sit with guitarist A’yen Tran as she hands out printed community principles to campers passing by—searching for their friends and preparing for the official start of the festival. Tran, who’s one of many attendees traveling between old-time conventions over the summer, tells me that the principles are a new, independent initiative by a diverse group of musicians who came together in 2021 to collectively address the discrimination of marginalized people in traditional music communities; this is the first time that the principles are making their debut at a festival. String band music has a long history of white supremacy, appropriation, and historical exclusion particularly of Black players, instruments—the banjo itself was created by enslaved people of African descent in the Caribbean—and old-time traditions, despite their being at the very heart of it. The principles acknowledge historical power dynamics within the old-time community and offer guidance on creating an inclusive environment for all players. Tran tells me that players were generally receptive to and supportive of the initiative, and many took flyers to their campsites.

“I think a lot of people don’t really know how to act,” says Jake Blount, an award-winning musician and scholar who specializes in the folk music of Black Americans. He, alongside numerous other musicians, shared input on the principles. “And that’s the source of a lot of the problems that we have…I think the community principles are a really good jumping off point for people who want to make the things that they control and are involved in more inclusive.”

Even with these calls for change, several recurring themes arise when people recall their positive experiences with the festival: it is a pilgrimage, an annual reunion for family and old friends and far-flung players. Clifftop is at once a time capsule and timeless, a visceral return to in-the-moment music making and the community gathering and inclusivity that are intrinsic to string band music. “To me, Clifftop’s like Brigadoon,” says musician Hilarie Burhans in a 2015 excerpt from Craig Evans’s documentary series, Conversations with Old-time Performers; at the 2022 festival, I hear others make the same comparison to the 1954 musical film. “It’s a whole beautiful community that rises from the mist, exists for nine days, and then it’s gone until the next year.”

Brittany Haas, a touring musician and old-time fiddler who is currently part of the quartet Hawktail, remembers arriving at Clifftop for the first time about twelve years ago, late at night. At that point, the entrance at which attendees pay an entry fee had shut down for the night. Rather than camp outside the gates, she and her group decided to do the “sneaky, punky thing where you just hike through the woods,” Haas said, “because we just couldn’t wait.” As they walked, Haas’s shoe broke. “I remember someone saying, ‘there’s snakes here,’ and just freaking out,” she recalls, laughing. “But then, wandering out of the woods into the campground and hearing all the music, it just kind of felt like this paradise of fiddle music coming at you from every direction.”

Clifftop is at once a time capsule and timeless, a visceral return to in-the-moment music making and the community gathering and inclusivity that are intrinsic to string band music.

On the first official night of the festival each year, Keith McManus, who some refer to as “the mayor of Clifftop,” hosts the Big Damn Morgantown Jam at his tent, which is known among campers as “McManustan.” The event is always enormous, packed, and rollicking, rolling into the early morning. Rachel Eddy, a West Virginia native and touring musician who’s been attending Clifftop since their early twenties, recalls that one year, it was so big that there was a bass on each corner of the tent. Normally, just one bass is present in a jam. “You don’t see that anywhere,” they say. McManus says that this year’s “McManustan” annual kick-off went until about 4:30 in the morning.

McManus is committed to keeping his tent as a place where everybody is welcome to play. For newcomers or beginning players, jams at any sort of festival space can be challenging to navigate or find your way into, and he, as well as the many people who orbit his tent, is committed to ensuring that anyone who’s excited about the music can play.

Some debate whether musicians should precisely preserve and imitate old-time recordings or if there is space to divert from purist tradition. Blount, however, framed those debates as irrelevant. He’s attended Clifftop since 2015 and is a two-time winner of Clifftop contests.

“I think recognizing that even right now, when we’re trying to emulate these old recordings that we’ve learned from, we’re making stuff up, right?” Blount tells me. His new record, The New Faith, is described as a “dystopian Afrofuturistic concept album…that features ten reimagined traditional Black spirituals” as well as two original spoken-word pieces. “We’re imitating qualities of the recording media, as well as the musician who was being recorded.”

“There’s a lot of assumption-making and fiction-inventing that goes on when we learn from those recordings,” he adds. “Most old-time music is historical fiction—it’s not any more real or accurate. People are just determined to present it that way.”

A walk around Clifftop is a submersion in universes of musical tradition without any closed doors. Players jam the woods with a full orchestra of instruments, not just fiddle, banjo, bass, and guitar, but mandolin, dulcimer, spoons, flute, clarinet, saxophone, harp, pedal steel guitar, and harmonica. I talk to a first-timer from West Tennessee who carries with him a bevy of homemade instruments, including a violin made from a cigar box. Multiple washtub basses—distinct with their silver bellies and single strings—are also in orbit.

One night, shortly after the fiddle contest finals, I wander down the hill from the Chestnut Lodge, past the food stand, and the vendors’ stalls of pottery, handmade banjos, violins, and vintage clothing, to a blue tent with a sign offering free fiddle lessons to anyone, regardless of level. And that evening, a handful of kids are seated in a semicircle, fiddles to their chins, following along with Lee Mysliwiec, who serves as a gentle ringleader, propelling the kids forward in song.

“What do we know in A?” he asks the group. The kids, who look to be between the ages of eight and sixteen and seem tired after a long day of playing, sit poised with their instruments. The mother of some of the kids, sitting to the side in a baseball cap, leans forward: “You all know ‘Cluck Ol’ Hen’!” Mysliwiec nods, and begins to take the group through the song. Later, he tells me about his own relationship to music, as a busker in Bloomington, Indiana, and why he spends much of his time at Clifftop teaching tunes to people for free. “I do it because I love to do it and I want to see people continue to play this music.”

In the Chestnut Lodge, various old-time players take to the stage to perform the tunes of prolific Appalachian musicians Ed and Ella Haley and celebrate the reissuing of their 1946 home recordings. Ed Haley, a player who performed throughout the region during the first half of the twentieth century, is often described as one of the best fiddlers of all time and is a figure that players continue to revere. He and his wife, Ella Haley, who often accompanied him on accordion and mandolin, were both blind. Over the course of more than six years, a group of archivists, musicians, historians, and audio engineers worked collectively to improve the low-quality 1946 home recordings that capture the Haley family’s music. The box set, issued by Spring Fed Records out of the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University, brings together more than 150 tunes and songs, including previously unreleased recordings. Archivist John Fabke tells the crowd that the record’s title, Stole from the Throat of a Bird: The Complete Recordings of Ed & Ella Haley, was drawn from an Irish poem about a blind fiddler whose playing is described as such, drawing a parallel to Haley’s “otherworldly” style of playing.

Musicians had the option to play Ed Haley’s fiddle, marked with a small red ribbon on its scroll, which has been in Bobby Taylor’s keeping for years. “You can hear the power and command almost take you,” Taylor says at the beginning of the release. “I always said that this fiddle, when I played it, it seemed to at some point take a mind of its own.…If you can imagine Ed Haley playing, no PA system, no nothing, he had to entertain.”

The new recordings are clear, yet carry with them the distinctiveness of what Haas describes as Haley’s “virtuosic” fiddling. She performs at the Haley release alongside Molsky, her longtime mentor who also introduced her to Haley’s tunes when she was ten years old. Through knowing Molsky “and people of his generation really well, I see how important things like [the Haley release] are,” she tells me. “You can hear all the notes really clearly [and] see…how much that means to the musicians who’ve been listening to that stuff for a long time.”

Steve Haley, Ed and Ella Haley’s grandson and a music transcriptionist, writes in the collection’s liner notes about what his grandfather might have thought of those playing in his style. “When someone once asked Ed if he would like others to play like him, he said that he wouldn’t mind if ‘someone patterned after me a little.’ Players today are not only doing that, but they’re taking it where music always goes—evolving into a new variation or a new interpretation, or melding dynamically with another genre.” Tessa Dillon, another West Virginia fiddler who performed, recalls the experience of getting into a different mindset, even with high-quality headphones, to be present through the static, to make out Haley’s fiddling; now, it is a privilege to have them accessible, cared for over years of restoration. Listening to her and others recreate Haley’s music, the fiddling feels alive and of the moment, the Lodge a vessel for tunes lovingly borrowed, as if from a bird.

Each day at Clifftop is full of little wonders: ’20s-style jazz in the distance at dusk, a parrot who sits on Riley’s shoulder as she plays, three generations of family jamming beneath a tent. Like many other first-time attendees, I’m at a loss for where to begin—and often find myself wishing I’d brought my fiddle, to try my hand at playing and by way of participating learn the whims of this intricate world. Even those who have been attending Clifftop for years say that full immersion in the festival can create a certain solitude, as each participant hops between jams and weaves their own unique tapestry of experiences. I meet other first timers on the crunchy gravel road that travels through the grounds, players from places like Germany and Ohio, solo and in search of a jam. And yet, there is a constant reminder of the proximity and presence of community—even if it might take some time to settle into a groove as a newcomer. Aaron Olwell, who’s been coming to Clifftop for over twenty years, remembers that some of his earliest feelings were sadness “that I didn’t know who to play with.” But, he tells me, “It seemed like within the course of a couple of years, [after] learning a few more tunes, getting to know more people, I couldn’t find the time to play with all of my friends in the course of a week or so here.”

Clifftop is ripe ground for experimentation and playfulness. There are events like the No-Talent Show, held at the so-called Cajun Tent, a sloping, yellow tent that’s parked in the “Bottom” area of the grounds, which has just four rules: no old-time, no Cajun, no bluegrass, and one minute per act. McManus recalls one of his favorite past acts, in which a mother, father, son, and daughter audibly honked, as the son turned a flashlight on and off. The audience playfully booed. It was then revealed that the piece was entitled “Where Are My Car Keys?” “It was so clever,” McManus tells me over the phone, laughing.

After nightfall at Clifftop, tents alight. So too does people’s hunger for singing tunes, for dancing. I come across a disco ball strung between the pines one night, people dancing to Hank Williams’s “Hey Good Lookin’,” the joy visceral and inviting; another night, at a tent with a sign that says “Big Gay Honky Tonk” in red print, a group sings “Paradise” by John Prine. “It seems like you hear the best music in the wee hours,” says Barbara Garrity-Blake, an attendee from Gloucester, North Carolina, and owner of the Cajun Tent, who’s been attending Clifftop for about three decades. “It’s like, ‘who are these magical fairies who are playing in our tent?’ Sometimes you can’t help but get up and join them.”

Rachel Eddy tells me that a number of years into their attendance at Clifftop, they began to think of the festival as a marker of time and growth. “The consistent memory is always feeling like I left Clifftop being a better musician, being more connected to the community, just feeling like I shed a skin for another year,” Eddy says. “I go into it at the end of my year and I come out fresh on the other side.”

On the last night of the festival, around 8 P.M., crowds begin to gather around the Cajun Tent, ready for the music that organically unfolds beneath it each night. People arrive, first in camping chairs, and then on the outskirts when seats fill up along the tent’s perimeter. I’d been sitting there for some time, chatting with Garrity-Blake and her husband, Bryan Blake, who brought their large tent to Clifftop. Over the course of about thirty years, their Cajun Tent has become widely known and beloved as a landmark of the festival. They’re now on their second tent, after the first became threadbare and ineffective against inevitable summer rains. They organized a fundraiser, and friends of the Tent rallied and raised around five hundred dollars to support the purchase of a new one. During that time, Blake recalls that people would come up to them and express how meaningful the tent was to them, saying that they’d met their bandmates, their future spouse under it. Last year, someone proposed under it. Looking ahead, Garrity-Blake says she’d eventually like to pass the tent on to somebody who will carry forth the rituals that it has come to host—including the No-Talent Show. “The Cajun Tent just always needs to be at Clifftop,” she says.

The couple used to fry four turkeys and serve them at midnight on Saturday, the final night of Clifftop. “You would turn your head for a second and then look back and it would be nothing but a carcass,” Garrity-Blake says. Though that tradition has subsided, they still like to make a big gumbo one night to share with whoever shows up, and other big meals, including one that centers ramps—a wild leek that is native to West Virginia—also take place at the tent.

Now, people gather with children in their laps, cups in their hands, for a final send-off into a night where the music never stops. Skip Williams, a longtime attendee and friend of the Cajun Tent, who from time to time makes beignets to pass out at jams and is one of many who helps to keep the tent running, sits next to me and reminisces about Clifftop’s past as campers walk by us, greeting each other like familiar neighbors.

“This is what I think of when it comes to Clifftop,” he says. “Smiling faces, eye contact, presence with everybody.…The fact that you can’t predict what’s going to happen.”

Right in front of us, in true Clifftop form, a rotating bunch of friends take to the center tent alongside musicians Joe Troop, Larry Bellorín, and Franco Martino; Troop and Bellorín currently play together as a group called Larry & Joe, and Troop and Martino were part of the band Che Apalache, which disbanded in 2020. Troop calls it a reunion of “Che Half-alache,” since just two of the former band’s members are present.

“This next song’s a game,” Troop tells the crowd. “You have to guess what this song is based on.” He says that he’s experimented with taking a classic Appalachian melody and filtering it through Argentinian and Venezuelan folk lenses, and jokes, “If you guess, you get a million dollars from Jeff Bezos.” It’s a song of longing, centering Troop on banjo and accented by nostalgic soars of clarinet. When it comes to a close, someone guesses it’s “Blow Your Whistle, Freight Train,” followed by another, correct, guess that it’s “Monte oscuro,” inspired by West Virginian Bill Browning’s “Dark Hollow.” It is a melodious and bittersweet close to the festival: cicadas murmur in the darkness around us, accompanied by a mix of original songs, voice-only harmonies, and at times, classic bluegrass and heartbreak with a twist.

Around 5 A.M. and many tunes later, I begin the walk back to my car down the hill. The night before it had rained, and now the earth is soggy and showing deep tracks where tires once sat, as campers have begun to leave. The morning is mostly clear, the moon bright and stars made softer by drifting wisps of cloud. I can hear some jams carrying out their last breaths before day, and already, I am envisioning Clifftops ahead: the fiddle I feel humbled and encouraged to bring by people who say it is not too late to learn, it never is. In saying goodbye to festivalgoers at the night’s end, there is a hope for, and perhaps even a certainty in, ongoingness.

Hours later, I’ll watch cars make their way past the Chestnut Lodge and turn to travel down a familiar road and away, many already certain of their returns. My dad and I will drive together to the land on which his grandparents’ farm once stood, now part of the New River Gorge National Park. We aren’t sure we’ll find it, but we’ll look anyway. Clifftop was described as a “library” by an attendee I met earlier that night, but I think about the impossibility of cataloguing the infinities of ongoing, overlapping and distinct combinations of musicians, playing tunes that will never be old or the same in a moment again.