The Long Wake of the Storm

Six years later, Barbuda still reckons with one of history's strongest hurricanes

By Justin Nobel

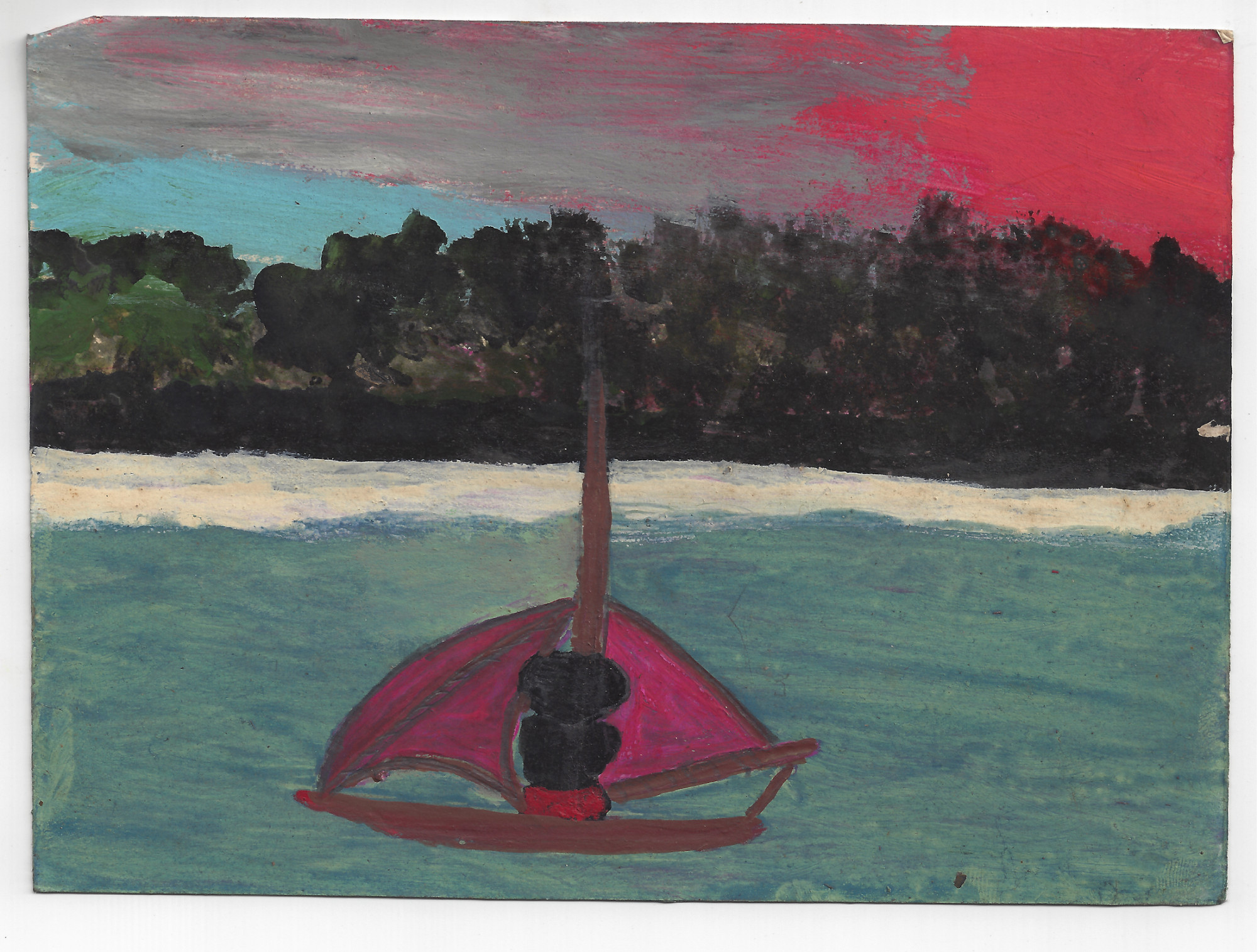

Painting by Frank Walter of Antigua (1926-2009). © Courtesy Kenneth M. Milton, Fine Arts Conservation.

Every summer, the Atlantic Ocean heats up and the hurricanes come soon after. While meteorologists plot their paths, Floridians, Louisianans, Carolinians watch closely, their lives, along with billions of dollars, at stake. But before storms can reach the mainland, many must first cross the Caribbean Sea, dodging the minefield of tropical islands that tend to weaken them and take their brunt. The dangers are considerable, though at least on Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, and even Sir Richard Branson’s private Necker Island, in fact most Caribbean islands, there are hills. The island of Barbuda has none. It is what some locals call “a little speck of sand.”

That is, a low limestone island, formed from old coral reefs, attracting no mass tourism, possessing a single village on the edge of a lagoon, with roads often blocked by tribes of goats and packs of donkeys, concrete homes with corrugated steel roofs, and a strong sense of community. “Barbuda is flat,” says John Mussington, the former principal and biology teacher at Barbuda’s Sir McChesney George Secondary School. It is roughly half the size of metro Atlanta. About a third of the island is wetlands and mangroves, another third is lowlands, only several feet above sea level, and a third is referred to as highlands, even though there are no hills, just elevated sections of limestone. “The significance of that in the context of what is happening on Earth is if you look at the predictions for climate change,” says Mussington, “in about twenty-five to fifty years, the highlands will become lowlands, the lowlands will become wetlands, and the wetlands and mangroves will be underwater.”

As was seen with Hurricane Katrina in 2005, along the Gulf, and Superstorm Sandy in 2012, in New York and New Jersey, the layout of a coastline can be dramatically altered, literally overnight, with the passage of a single storm. And in early September 2017, the storm of storms approached Barbuda, resembling on weather radar maps a tightly rotating circular saw blade, with a perfect eye and almost unprecedented 185-mile-perhour sustained winds. According to Wayne Neely, a Bahamian meteorologist and author of several books on Caribbean hurricanes, it made this hurricane, called Irma, one of the strongest seen in the Atlantic Ocean since record-keeping began in 1851.

“One interesting thing about Irma,” says Neely, “is just before hitting Barbuda it went through an eyewall replacement cycle.” When a storm develops a second eyewall away from the middle, the inner eyewall fades, and the second one contracts in and replaces it. “Like a lobster, or a snake, shedding its old skin to make room for something bigger,” he explains. By September 5, the storm was at “the upper bar, about as strong as Atlantic hurricanes get,” says John Cangialosi, senior hurricane specialist with the National Hurricane Center. “We’re probably talking about wind gusts over two hundred miles per hour.” And in the late hours of the night on September 5, and on into the early morning of September 6, this monster passed directly over that little speck of sand.

“The island of Barbuda was once a Caribbean paradise, now it is lost,” the BBC and CNN later reported. “Hurricane Irma has reduced it to rubble.” A French news channel sent a film crew, Vice filed a dispatch, as did the New York Times, and then these large media organizations moved on, as they do, because the world is wide and rich with disasters and eventually other hurricanes tracked across the map. Jose, Maria, Dorian, Humberto, Henri, Ida, Ian, and the names of course will keep on coming. But what about the people back on Barbuda? What really happened that tremendous tropical night? The island has 1,600 residents, and around 1,400 people were on Barbuda when Irma hit. If Irma was one of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded in the Atlantic, then those who lived to tell the tale had been through something truly extraordinary.

And yet “the bigger story,” explains Claire Frank, one island resident originally from the UK, who runs an art café, is the selling off of Barbuda land, and the destruction of the environment by so-called investors. The likes of Robert De Niro, the mob boss from the Godfather movies; and John Paul DeJoria, the polished billionaire philanthropist who was once homeless and now runs a tequila empire, a hairdressing empire, and a pet grooming empire, and also has holdings in diamonds, motorcycles, and natural gas.

“Now,” Frank says, “we are losing everything to billionaires, and not the weather.”

Drop down into morning on the island of Antigua, the larger, more developed, and more populated island of the Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda. A ferry, the Leeward Express, is about to depart on the roughly forty-mile journey for Barbuda from the Antiguan port of St. John’s, but it can’t leave yet because two gigantic cruise ships are docking in the narrow tropical harbor. Cargo has been secured beneath a tarp, and passengers wait patiently in their seats. Above, in striking black-and-white profile and so large it seems like a small plane, soars a frigatebird. With a wingspan the length of an NBA player and the ability to fly for weeks, they are the avian queens of Earth’s tropical seas, and one of their most prolific colonies on the planet is in a patch of mangroves on the west side of Barbuda.

On the open-air deck of the ferry bound for that island is Avanella John, who works in tourism and has her hair in magenta braids wrapped in silver and gold wire. As the cruise ships perform their final docking maneuvers, she drifts back five years, to the night that Hurricane Irma arrived. “I went to bed,” says John, “and when I was there laying down I felt dust falling on me.” When she looked up again, her roof was gone and she could see the storming night sky. She darted into her kitchen, tossed out her pots, and crawled, along with one of her sons, into the cupboard. There they spent the storm, listening to the unsettling noise of the wind tearing the village apart.

After the ferry docks in Barbuda, the story continues at the island’s firehouse, with fire chief Neil George wearing a sharp blue uniform and speaking from behind a glossy desk. “We got here about seven or eight at night and were cooling out. At about ten, the wind really picked up. Bolts and galvanized steel were starting to come off the roof. We could hear individual nails being sucked out, then shot into the night. Our vision was getting white and blurry because the hurricane was sucking the oxygen out of the building. Our fire and rescue pickup truck, parked right outside the station, was kind of levitating in the wind. I was here sitting at this desk, in the corner of the room, and someone said, ‘Hey man, look, you should sit over there,’ and they made me move to the center of the room. Just then, the roof collapsed.”

The force caused the firefighters to fall to the ground. “And we went into the cupboards,” says George.

But how do eight weighty firefighters fit into a set of cramped kitchen cabinets? George chuckles, and recalls wisdom his grandmother used to say: “At night, everyone fits.”

“We started to be bombarded with calls,” he continues. “We had told ourselves we are here to work, and we have to go out and rescue people, that’s our job, but our roof was gone and we couldn’t move. We just heard that wind, and we were thinking, what is happening out there right now? We were called by one family, they had a two-weekold child and their roof was gone. Still, we couldn’t leave, the storm was too strong.”

“Twenty to twenty-five minutes later the eye came,” says George. “We opened the door, took a look around, and I said, ‘this is a real country mashup.’ That’s country talk meaning, it’s a wreck.”

Most Barbudans had remained in their homes, but many had gone to formal shelters. They included a community center; a fisheries building; two different churches, the Pentecostal and the Peoples Church; and also the hospital. At the community center, damage was severe and people sheltering there had to be evacuated. The Peoples Church was breaking apart. The Pentecostal church was flooding. The fisheries building and hospital were withstanding the storm all right, and all those in crumbling homes or shelters could be moved there, but before anything could be done, the debris-littered roads had to be cleared. Then there was the family with the two-week-old baby that had called during the storm, and a pregnant woman the firefighters had to take to the hospital. “The eye gave you a half-hour to three-quarters-of-an-hour window to work with,” says George. “Once winds on the other side of the eye wall start up you have about fifteen minutes.”

The firefighters retreated to the hospital. “I could hear songs,” says George. “BLU-DONG, BLING-BLUNG-BLAM! BLU-DONG, BLING-BLUNG-BLAM!” When the storm ended, and dawn came, the firefighters went outside and George realized this noise had come from forty-foot-long shipping containers being tossed about like toys in the wind. He believed the island was going to be covered with casualties, and the firefighters prepared to take down the names of the dead and gather bodies.

“By 2:30 p.m. the prime minister came to Barbuda in a helicopter,” says George. “I met him at the airport and gave a status report of the island. I told him, at least ninety-five percent of the homes have been destroyed, but only one person died, a small child. The prime minister made a phone call right in front of me, and he said, ‘Barbuda has been decimated.’”

Down the street from the firehouse, near the center of the village of Codrington, is a bar called the Green Door. The door is open, and sunlight bursts through, a perfect rectangle of it, and into the dimly lit bar space, where there is weed smoke, a string of green party lights, and music coming from a large stereo tower resting on an empty crate of Carib beer on the concrete floor. Byron Askie, who runs the place, is busy making rum drinks.

“When the storm came, I was in the bar,” says Askie. “Something was wrong, because of the birds, the trees, the sea, you sensed something very serious coming. I could just feel it. I said this is not going to be a regular hurricane. I realized I had to close up because the wind was increasing. I tried to secure the building. I put up plywood, I put up strips of wood, and I waited.”

It is a small Sunday crowd, but they are energetic and adamant, and somehow Askie, who wears khaki shorts and muck boots, is constantly occupied serving a drink to someone, though still able to work in his tale of the storm. That night, as the winds increased, he realized he had to leave his bar and check on his mother, who lived right next door.

“She was all by herself,” says Askie, “and I figured that was where I needed to be. At ten that night the storm picked up in earnest. At eleven the nails from the roof started blowing away; you could hear them popping out then zoom, they’re gone. Then the plywood started sailing in the wind, the water was coming in. I said ‘What the hell is going on?’ My mother and I saw a roof blow away in the wind together, turns out it was hers.”

“As Barbudans, we think a hurricane is something of the norm, we are used to storms in Barbuda, it brings the family together. We stay in the house and eat and drink, and we play dominoes and cards, I like that. It only happens once in a while. But all my life I have never seen a storm like this one. In my room there is a closet, and I went in there, and my mother went into her closet, and there was no communication. I cannot tell you why we were not in the same closet, but she was crying out, although I couldn’t hear her then. I never prayed before during a hurricane, but in this hurricane I prayed, ‘Oh dear Lord, spare our lives.’ And we rode out the first half of the storm like that, alone in separate closets in the same house unable to communicate.”

At the Green Door, the sun’s angle in the doorway sharpens, and an elegant woman with a nose ring walks in, takes out her purse, and asks Askie if he has Guinness? Gin? Good wine? She settles on a gin and tonic. “That’s a good drink,” says Askie. “Sorry I don’t have any lemon twist to put in it for you,” and he hands her the drink, then motions through a small door in the back of the bar. There is something he would like to show off.

“This building was built in 1957,” he says. “It’s the oldest business on the island and we never had a problem with it, so I figured it was strong, and it would withstand whatever was coming—but I was wrong, it was ripped apart.”

He sloshes through a large back room, dark and flooded from recent record-breaking rains. Before Hurricane Irma it was a discotheque. “I had bought all the necessary items,” he says. “I had the mirrors, the balls, DJ equipment, it was beautiful.” But he lost everything when the roof went, although somehow one disco ball is still hanging in the room’s center. And he is working as hard as he can to put the rest of the pieces back together. “I wanted to open the spot back up for Christmas,” says Askie, “although the money is not here yet.”

He sloshes deeper into the floodwaters of the ruined disco—there is something else he would like to show. He goes out a door that leads to a small courtyard then into a narrow back room, also flooded. “My father went to New York in 1941,” he says. “He worked as a plumber in the day, and at night worked at Sylvia’s Restaurant,” the famous soul food spot in Harlem. “They were always about chicken at Sylvia’s, and he introduced them to fish, Caribbean style,” says Askie. In 1947, his father met Louis Armstrong at the restaurant. “If you go to Sylvia’s today, you will see a picture of my father up on the wall,” he says. From a shelf crammed with junk in the flooded back room, he produces a dusty case, wipes it off, opens it up. Inside, rusted and in need of a shine, is a trumpet. He says it belonged to Louis Armstrong.

During the reprieve of the eye, Askie went upstairs to the second floor of a guesthouse beside his mother’s home, and his mother went next door to her brother’s. “When I came out in the morning I looked out and could see all the way to the sea on the east coast, because the island was leveled,” he says. “You saw the electrical poles and the wires, how they were wrung around, the trees were twisted, and all the branches of the trees were gone, even the animals in the fields, the horses, the donkeys, the goats, the sheep, the birds, they were all over the place, dead.”

“Irma was a beast,” he continues, “and I don’t know where it came from but it ripped Barbuda apart, and I hope to God it never returns. They said it was a Category 5, but if there was a category 10, or 20, it would have been that.”

Photograph by Mohammid Walbrook. Courtesy the artist

The Bahamian meteorologist Wayne Neely has traveled to archives and libraries in France, England, and across the Caribbean in search of records and says the first instance of the word “hurricane” can be traced to Mayan hieroglyphics, which describe a deadly storm that struck in 1464. Hurricanes were feared, and the Mayans did what they could to temper their wrath, building most major cities away from the coast and appealing directly to the storms themselves.

“Every year,” Neely writes, “the Mayans threw a young woman into the sea as a sacrifice to appease the god Hurrikán.” They also sacrificed a warrior, in order to “lead the girl to Hurrikán’s underwater kingdom.” Other Indigenous Caribbean cultures tell of a similar god. On Saint Kitts, there was Hurry-Cano; in Guatemala, Hunrakán; and the Taíno people, who came originally from South America and lived across the Caribbean Islands, had Huracán. Still, we do not know for certain which group came up with the word first, says Neely.

What we do know is that hurricanes can do a lot more than demolish homes and redefine coastlines. These storms can crumple entire civilizations, or leave a land and its people so weakened and disarrayed that new forces come in and drastically alter a place. A man with a bushy beard named Mohammid Walbrook is driving rapidly down Barbuda’s River Road, which leads south out of Codrington to the ferry dock and is filled with potholes, goats, and the occasional chicken. At the ferry dock, Walbrook pulls onto the pier so his passenger van is pointing beyond the blue-green shoals to a distant white fringe of sand and the green stripe of land above. Palmetto Point, the future site of a compound that will include million-dollar homes, dinner clubs, and a golf course.

“Peace, Love, Happiness,” says Walbrook. Or PLH. It’s the project of John Paul DeJoria, the tequila and hairdressing magnate. “Since Irma,” says Walbrook, who works as a driver and guide for tourists on the island staying at a set of cottages run by Barbudans, “it has been a huge land grab for anyone who wants to come in.”

On the island’s gentle southern coast, Robert De Niro aims to open a club on the grounds of an older resort called the K Club, established in the 1990s by the famous Italian designer Mariuccia Mandelli and frequented by Saudi princes and Princess Diana. But De Niro’s hangout, to be called Paradise Found, promises to take things to the next level, and according to the website luxurytraveladvisor.com, will have not only a spa and four restaurants, but a marina that can accommodate super yachts. A private airport is being constructed in the middle of the island, to jet in all the new ultra-wealthy tourists. A third luxury residential complex, part of the PLH project, is planned for Coco Point in the island’s south. Neither DeNiro nor PLH have responded to questions or requests for comment.

After Hurricane Irma, Walbrook worked for the Red Cross, helping islanders rebuild, an arduous process that involved paying for them to travel by ferry to a hardware store in Antigua and handpick the supplies they would need to reconstruct and strengthen their homes, many of which still remain in some state of disrepair. In a controversial decision, just after Irma, Antigua and Barbuda’s prime minister Gaston Browne forcibly evacuated the entire island to Antigua. While many Barbudans, such as fire chief Neil George, defend the decision and believe it was necessary, as a second major hurricane was approaching, Walbrook and others saw it as a reason to get people physically off the island so a handful of mega development projects loosely in the works for years but opposed by many Barbudans could gain a foothold while Barbuda was empty and on its knees.

“While we were off the island,” says Walbrook, pointing across the tropical bay tothe new PLH development, “these guys were taking in equipment and workers.”

“Palmetto Point,” he continues, “is where we used to go for sea grapes. Some people made wine with them. During certain times of the year we had coco plums; they grow along the beach. We have these big gray land crabs on Barbuda, and that was one of the best places to go for them. Some people used the land for farming. We had cattle, horses, and deer too, which is one of the wild foods that we eat. Palmetto Point is also one of the best kept secrets in the surfing community. The waves can be twenty feet tall and are said to be some of the fastest in the world, and it’s a sandbar, so if you fall you don’t hit a reef.”

But now all of that is off-limits, or extremely hard to get to. Of the four dirt roads that used to cut south from the River Road through the brush and mangroves to Palmetto Point, every single one has been closed off, says Walbrook. And the main road onto the point is often guarded by a PLH security official on a dune buggy.

The website of the Barbuda Ocean Club, the entity behind the PLH project, features a video montage: A pair of women with drinks in their hands lies head-to-head on cozy cushions on a powerboat skimming across the waves, driven by a stylish young man with blond hair. A woman does yoga in front of swaying palms. Smiling shiny millennials share drinks in an infinity pool. “Barbuda Ocean Club,” says the website. “A members-only community where families live simply, pursue passions, and create lifelong memories. Spanning over 800 acres of untouched paradise.”

“Our demographic is successful wealthy guys,” Michael Meldman told the New York Post in 2021. Along with John Paul DaJoria, Meldman, who operates private resorts around the world under the Discovery Land Company, is one of the main developers behind Barbuda Ocean Club. Land, the article states, starts at $3 million a plot, and only private jets will be allowed, bringing in London elite and Wall Street bankers. “This is a place where masters of the universe let down their hair, where wild horses drink straight from the pool, where sea turtles flap their flippers right along the shore,” said Meldman. “It will be like if you made St. Barts private and really limited the people who go there.”

On interactive maps, prospective buyers can look at homesites, located in either Palmetto Point or Coco Point. There are to be the West Beach Estate Lots, the South Shore Estate Lots, the Lagoon Cottages, the Brosnan School of the Environment, the Organic Farm & Dairy, and the Welcome House. All of these names are written in a font that somehow gives off the look of glamor and safety. The rutted roads and timeless bars, the sea grapes and coco plums and wandering goats and dents and crags and hardened, weathered features and the names and places that truly make up the island of Barbuda appear to have been stricken from the map.

Around 1685, King Charles II of England granted a lease for the entire island of Barbuda to Christopher Codrington, an Antigua planter, and his brother John. Barbuda was essentially a low, flat, rocky limestone table with no volcanic uplift, poor rainfall, no precious minerals, and none of the fertile volcanic soil or alluvial deposits that enabled sugarcane plantations to be established on other Caribbean islands. Instead, enslaved people on Barbuda raised small crops and livestock, fished, and harvested timber for the Codrington plantation and markets in Antigua. Records indicate that in 1825 there were two white overseers and about four hundred enslaved people on Barbuda. Among them were doctors, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, shoemakers, sailors, sailmakers, seine netters, shepherds, watchmen, water drawers, coopers, masons, and carpenters. “The Barbudan slave community was remarkable for its autonomy,” writes Caribbean anthropologist Riva Berleant-Schiller. “Equipped with guns, horses, dogs, and boats, they had free run of the island and its resources.”

Robert Jarritt, a Codrington agent in Barbuda, described the island’s enslaved population in 1829 as “a bad sett, insolent, ungovernable, and almost outlawed.” He reported that many refused to work for Codrington and chose instead to tend their own provision grounds and shoot game for their own consumption. He recalled an episode in which five enslaved people who had been jailed for assaulting a slave driver were freed the next night by a gang of their compatriots. “They acknowledge no Master,” Jarritt wrote, “and believe the Island belongs to themselves.”

But of course, it didn’t. “Slavery was still slavery,” writes Columbia University Caribbean historian Natasha Lightfoot in her book Troubling Freedom: Antigua and the Aftermath of British Emancipation, “and African-descended Barbudans’ bodies were the property of the Codringtons.”

In 1834, Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act, outlawing the owning, buying, and selling of humans as property throughout its colonies. For Antigua and most of the Caribbean, what came next was the apprenticeship system, “devised by the British Parliament to give slave owners and their allies continued control over freedpeople’s mobility,” writes Lightfoot. But since the entire island of Barbuda was private property belonging to the Codrington family, Antigua’s laws had no jurisdiction there. And “the Codringtons,” writes Lightfoot, “never made any provisions for their former human property.”

Thus, the Barbudans were in a legal limbo. Nowhere was it written that the land was theirs. But anytime outsiders attempted to take the land or push various development schemes, Barbudans used the chance to reestablish their right to farm, graze, and live upon the land. In 1860, when the Codringtons’ manager complained that Barbudans’ small agricultural plots and livestock were too freely scattered about the island, Sir William Codrington ordered Barbudans not to “cultivate or occupy any Garden or Land beyond the distance of two miles from the village” and directed that goats, sheep, dogs, and other animals were not to be kept without permission. Barbudans protested these restrictions and continued the forbidden activities. “Codrington could not succeed in shaking the productive relations of Barbudans with their island,” writes Berleant-Schiller, “and consequently did not succeed in commercial development.”

The Codrington lease ended in 1870, and in the 1890s the Crown leased the island to the Barbuda Island Company, which attempted to develop tracts of coffee, cacao, and sisal, crops that required exquisite care, large capital investments, a good water supply, and reliable labor. Barbuda did not have these things, and the project failed. The British then tried to establish a government cotton plantation, which also failed, for similar reasons. “The desire of the people… appears to be to revert to a condition in which no permanently cultivated Government Plantation can be worked owing to the uncertainty of labour supply,” stated the Crown’s agricultural inspector in 1916, “while they themselves run stock and work ground without restriction.”

Riva Berleant-Schiller, who published her fundamental paper on the history of Barbuda’s land policy in 1978, in the Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe (Bulletin of Latin American and Caribbean Studies), believes it was the Barbudan people’s ability to successfully adapt to their “meager physical environment” that strengthened their community and sculpted their identity. And there is more to it than this: Developers have consistently overestimated the Barbudan environment in being able to provide commercially and create fortune, and have continually underestimated the Barbudan people’s ability to resist lavish and extractive projects in favor of doing their own thing. “Barbudans,” Berleant-Schiller wrote, “continue to believe that the island belongs to themselves.”

This, despite what it actually says on paper. In 1981, the islands of Antigua and Barbuda were at last formally cut off from England by a royal decree signed at the Court at Buckingham Palace. Suddenly Barbuda’s largely self-preserved system of communal land ownership was brought into the fold of the central government in Antigua. And Antigua, writes Natasha Lightfoot, has since virtually day one of this relationship been involved in a project to “court international investors for deals to develop Barbuda as a playground for the global jetset.”

In 2007, under leadership of the United Progressive Party, the government in Antigua passed a law that for the first time secured in writing the idea of communal land ownership that had prevailed for centuries. Written into the record were words saying that no land could be sold and no person could acquire the ownership of land in Barbuda, and that every Barbudan was entitled to the use of up to four plots of land—one for residence, one for grazing, one for crops, and one for commercial purposes. But in 2014, a new political party was voted into power in Antigua, led by the present prime minister, Gaston Browne, who has recently swooned Western media with his talk about the world’s wealthy countries causing the climate crisis and poorer nations such as those in the Caribbean paying the damage.

"Barbuda has no natural freshwater storage,” writes the prime minister’s chief of staff, Ambassador Lionel Hurst, in an email. “All water has to be desalinated, which is an expensive process. All food, except fresh fish, has to be imported from Antigua and sailed over to Barbuda on small vessels. All building supplies enter Barbuda from the Antigua hardware stores and are placed on barges.” And all of this, Hurst says, makes “low-density hotels the only possibility.” In essence, Barbuda must be “a luxury destination.” And Prime Minister Gaston Browne’s government, Hurst continues, “is making the best use of its available resources to the chagrin of the do-nothing opposition.”

In July 2016, the Antiguan government amended the 2007 law on Barbuda’s community land rights, giving any individual or corporation the ability to receive a ninety-nine-year lease for land on the island, independent of the approval of Barbuda’s governing body, the Barbuda Council. Hurricane Irma has acted as an accelerant, says Lightfoot, allowing the Antiguan government to strategically erode Barbuda’s system of communal land ownership in the name of rebuilding and “‘fill’ it with disaster capitalist projects of all kinds.”

Right after Hurricane Irma, Prime Minister Browne held a town hall meeting for Antiguans and Barbudans in the Bronx, where there is a sizable expat community. At the meeting, the prime minister called Barbuda a “welfare island” and said Barbudans’ sense of a legal right to communal land was a “myth.” Later that year, Browne told the British newspaper the Guardian that those opposing development in Barbuda were nothing more than “a handful of deracinated imbeciles.” This statement was aimed at “groups of Barbudans” who protested the prime minister in London and New York and were seeking to discourage Hurricane Irma recovery assistance to the Government, says Hurst, the prime minister’s chief of staff. On the issue of communal land, Hurst says the matter is settled. “The land in Barbuda is owned by the Crown, not by the Barbudan community,” and “the Sovereign Government of Antigua and Barbuda determines to whom land is sold and in what quantities,” says Hurst. Profits go to the Treasury of Antigua and Barbuda and recent monies have gone to build a runway and an airport terminal, construct a seaport, and to the Barbuda Council to meet its regular expenses. Hurst added, “The prime minister does NOT make or receive any compensation from leasing land on Barbuda.”

In January 2023, the prime minister's party was victorious in general elections, and Gaston Browne was re-elected for a third term.

On the edge of the lagoon, in the fading daylight, with purplish thunderheads building far out over the ocean, the former biology teacher and principal at Barbuda’s Sir McChesney George Secondary School, John Mussington, arrives on a bicycle, wearing a sporty top and dress shoes. He speaks at length to a fisherman readying his boat for the evening, then comes around to a section of pier badly damaged in the hurricane and takes a seat on the side of a low concrete wall. A man nearby is offering tours to the famous frigatebird colony, though there’s only one tourist around.

“For most people living in the developed world, what’s your biggest problem now?” he asks. “Pollution. The climate crisis. But the idea that you can own the Earth is what ended us up in the climate crisis in the first place. The clientele of places being built now on Barbuda, like the Barbuda Ocean Club, is rich people who want to get away from the pollution and all of the destruction which is caused by climate change, which they created. They want to buy a house in paradise. And they now have the means to find these clean virgin places and build homes there. Only if you are a billionaire today can you move to a place with a clean environment. And that becomes a problem for Barbuda.”

“We didn’t cause the climate crisis,” Mussington continues, “they did. But they have the resources to find our enclaves and take our resources from us, and basically run us off the island. And so, these last places on planet Earth that are still protected and still clean become at risk of being lost by the same polluters who have created the reason to run in the first place. They may not believe in our communal system of land ownership, they tell us that the system we have is no good, it’s backwards, we have to give it up to be modernized. But we know differently, we know that way of life is what has created Barbuda and preserved the pristine environment that they are drawn to. The logic is on our side, not theirs.”

Mussington is now retired but still keeps quite busy, attending meetings, reading and researching, holding the flame of the island’s history and struggle in his palm. While it sometimes might appear that he is a one-man resistance to the onslaught of the billionaires and their development projects, he does have others on his side, and his work as teacher and principal has given him a high profile and an ever-changing new set of young minds to educate. He proudly conveys that the students of Barbuda’s Sir McChesney George Secondary School were among the winners of a global program on climate-smart farming sponsored by the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation in Agriculture. Students at the secondary school, he boasts, don’t just take academic courses—they change into work clothes and do landscaping, and have adorned the school’s grounds with shrubs and trees and flowers, making it one of the most beautifully vegetated spots on the entire island. But as great as his contributions have been, there has been resistance too, a concerted effort by the Antiguan government, he says, to label him as eccentric, outdated, and outright insane. “We are up against billionaires,” says Mussington, “with the best lawyers and the best scientists that money can buy. And these people, and our own government, are telling us communal land is backwards.”

The only death on Barbuda during Hurricane Irma was that of two-year-old Carl Junior, and it’s a death many people in Barbuda still think about, none more so than the family that experienced it. They were trying to seek better shelter during the storm, but unlike the rest of the island, able to hold out until the calm of the eye, they were making a run for it during the hurricane’s peak winds. “You must understand,” says Carl Francis, the boy’s father. “The roof had blown away, and one side of the house.” And he didn’t have enough strength to carry both his three-year-old son, Jeremiah; the children’s mother, Stevet; and also the baby, Carl Junior. So another woman with them was holding Carl Junior, and she got pelted with debris and somehow must have let go, because suddenly the baby was gone.

For an island hit by a storm ranked as one of the strongest in recorded history to suffer only a single death is by all accounts remarkable. “I mean, there is no way to look at that but just amazing,” says John Cangialosi, the National Hurricane Center hurricane specialist. “It speaks to the resilience of the population there; they respected the storm, they took shelter—they did all the right things.” And Mussington believes it is the island’s unwritten code of communal land that is responsible.

Every story is more complicated than the sum of its parts—first you have to ensure that you even know all of its parts. Above a stretch of pink sand beach and palm trees near the ferry dock is a beachside shack called Sunset Delight. Here, proprietor Shaniqua Nedd has on a local radio station blaring smooth love songs and is doling out drinks to a group of men. Among them is James Jermaine John, who goes by Boon, and Matthew John. Boon is muscular and wearing a tank top; Matthew is dressed more formally, in a collared shirt that is blue like the sky. “Every day, a Barbudan is speaking about Irma,” says Matthew. “Every day.”

These men have their storm stories too. They say the storm hit at night. It began to get very bad around ten or eleven and lasted until five or six in the morning. Most people were home and hid in the bathroom, the bathtub, the narrowest place they could find. During the eye there was a calm, and that’s when you tried to get to better cover, a home with a concrete roof rather than a corrugated steel one, or a formal shelter. Come morning, says Matthew, “it was like a nuclear bomb had gone off.” The island’s structures were largely destroyed, but there was just the one death, two-year-old Carl Junior. More people did not die, says Boon, because of the island’s strong sense of community. “Me and you, we’re enemies,” he explains, “but when it comes to the storm, we’re friends, and you let me in.”

But that is just the thing. Now there are new things happening on the island, and newcomers. The line between friend and enemy has become fuzzy. For some Barbudans, these newcomers threaten the island’s unique system of communal land and the very thing that makes Barbuda Barbuda; but for others the influx has meant work, and an opportunity to better their situation and that of their beloved island. Matthew works as a tour operator, dealing with tourists who come on day tours from Antigua, as well as visitors that arrive on private yachts and super yachts. He takes people to the frigatebird colony, the beaches, the caves on the far side of the island, and says that “we give them a nice drive around the village, we show them the island life.”

Boon also works in tourism, as a landscaper for PLH. And his mother, Avanella John from the ferry, works for the project too, as a supervisor. “Some people are worried about certain policies,” says Boon. “I do not agree with all of them, but otherwise I have a job, that is the main thing, and the company takes Barbudans as a first preference, and they treat us well. It has brought a lot of progress for young people like me.”

“Hopefully, in the future it can lead me to other places,” says Boon. Discovery Land Company has developments in other parts of the Caribbean, and all over the world. But as much as working for an international tourism development company excites him, nothing excites him more than staying right here in Barbuda. With the new income and security gained from the job, Boon says he intends to bring something to the village of Codrington that doesn’t currently exist, at least not in the way he intends to do it—“I am looking to open a supermarket.”

Time rolls on. The Earth rolls on. The waves roll on. “The unreal way in which it is beautiful now,” wrote Antiguan American author Jamaica Kincaid, “is the unreal way in which it was always beautiful.”

“At the end of this sentence, rain will begin,” wrote the Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott. “At the rain’s edge, a sail.”

The seas have climbed, fallen, climbed, fallen, risen before. When they rise the next time, as they are indeed rising now, it may be the people who, forced by their meager environment and historic circumstances, have developed a different way of living that survive. Byron Askie, who runs the oldest establishment on the island of Barbuda, the Green Door bar, and who says his father once worked at Sylvia’s in Harlem, met Louis Armstrong, and took home his trumpet, worked for years himself in New York City at a restaurant just beside Rockefeller Center. He says he met Robert Redford, Julia Roberts, Evelyn “Champagne” King, and the soccer star Pelé. He loved New York, and he loved that job. But right now what he would love more than anything else is to drain the floodwaters, put back up all of the disco balls, and reopen his discotheque. It seems incredible that outside entrepreneurs, tequila moguls, and movie stars from New York and Los Angeles can get money to build whatever they want on the island, when they have absolutely no roots there. Yet a local entrepreneur with a functioning business is still wading through floodwaters in muck boots five years later, trying to save up enough from beer and rum sales to repair his roof and reestablish his business.

“Sometimes,” says Askie, “I call myself Lord Byron,” after the poet. And he too has written a poem. “It’s about the frigatebirds,” he says, “because I think myself one of them."