Crab Anatomy

By Baylea Jones

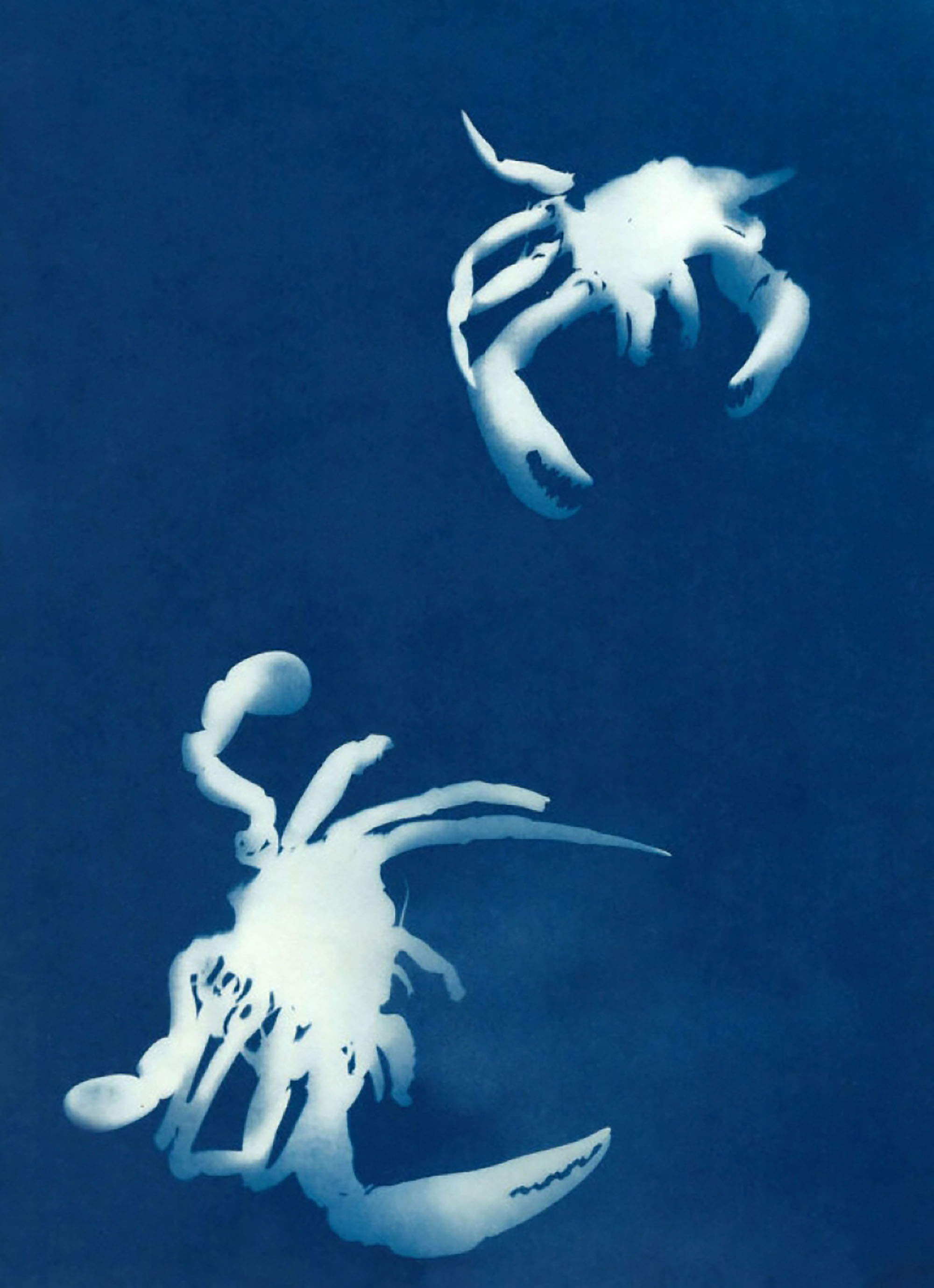

Two Blue Crabs (Callinectes sapidus), 2014, a Cyanotype print by Alexis Doshas. Courtesy the artist

Carapace is a word my Southern tongue can’t wrap around. It means a hard, protective outer covering. A carapace is a shell. Cajuns eat anything with a shell—crawfish, crab, shrimp, even turtle. We like to work for our food, make a day out of it. A party. We sit around peeling crawfish shells back like fingernails, sucking the juices out the heads, plunging the meat into homemade dipping sauces, and popping the tiny tails into our mouths. It takes a hundred crawfish to feel full, but we’re there for the experience. Newspapers draped over picnic tables; boiled crawfish, corn, and potatoes piled in the center. We are community eaters. We talk with our hands, we eat with our hands, we talk while we eat.

Pawpaw teaches me how to crack open crab shells. We’re sitting at the kitchen table. Mawmaw’s got her frying station set up behind us. A white ceramic bowl filled with Tony Chachere’s seasoned flour, another filled with a whisk of milk and egg. She dunks the crab bodies into the egg mixture, then the flour, back into the egg, and a final dredging of flour. She uses one hand for the dry ingredients, the other for the wet, somehow never mixing the two. She plops the battered crabs into the sizzling cast-iron pot. They fizzle and float. She fishes them out one by one with a metal spoon and places the golden bodies on a cookie sheet lined with paper towels to collect any excess grease. They’ve got me salivating. The smell of hot oil and browned batter.

We let them cool, our impatient eyes waiting for the shells to stop hissing with heat. Pawpaw reaches for one and gets to work. I try to mimic his movements, but he is too quick. He is looking at me, not at the crab, as his hands move fluidly, guided by muscle memory like he’s solving a Rubik’s Cube. I clutch a freshly fried crab body, stripped of its legs and carapace, in my small palms. I dig my fingers into the spine and push my thumbs until the body breaks in two. Pawpaw nods. Now, he’s fanning out the meat and plucking out sweet white bits to eat. I have somehow fallen behind. My bounty doesn’t come as easily. The shell slices my fingertips as I reach into the crevices, only managing to pull out a few morsels at a time. He’s on his third body while I’m still working on my first.

Like this, he says. Pawpaw is a shower, not a teller. He demonstrates again. Cracks the body in two. Crushes one half in his fist. Out fans the meat, bright white and succulent. I try to do this, but I crush too hard or not hard enough. Either way, my meat is still stuck in each unreachable pocket that I must excavate one by one. I never would learn his magic trick. Over the years, my way—slow, careful, methodical—will become mechanical.

Pawpaw loves crabs. He loves crabbing in the early morning twilight in a pair of white rain boots locals call Hackberry Reeboks. He loves throwing crab traps out over the Gulf and pulling them back in heavy and full. He loves sitting at the kitchen table enjoying his catch, cracking the claws open and tearing into the meat. He loves dipping them in the sauce he teaches me how to make—mayo, mustard, ketchup, and a few secret ingredients. He loves fishing and shrimping and crabbing and sharing all of this with his family. This is his legacy.

The blue on a blue crab looks painted on, carefully brushed along its legs and edges. The blue and orange blaze against the white and brown shell. A blue crab is a poem. Callinectes sapidus. Beautiful, savory swimmer.

My mother is a crab. A Cancer. Cancers are water signs with hard exteriors and soft underbellies. They are intuitive, moody, and ruled by the moon. A Cancer’s opposite sign is a Capricorn. The horned goat. My mother’s opposite is me. A Capricorn. Two polar signs that can either balance each other out or butt heads. We are the latter. I am serious and mature; she is emotional and needy. We love each other fiercely but never seem to land on the same page.

My mother got cancer during Cancer season. She was diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma three days before her birthday, a year after Pawpaw’s death. One week, her white blood count is too low to undergo chemo, and the doctors prescribe crabs, her favorite like it was her father’s favorite. Crabs are rich in selenium, a nutrient that boosts the immune system. Selenium is from the Ancient Greek selḗnē: moon. The cancer and the crab. The crab and the moon.

To fill my mom’s prescription of crabs, my wife Britney and I meet up with my mom and Mawmaw for a crab boil at my Uncle Kevin’s river house in Texas. Britney and I fetch the crabs from the holding pen. We drive down from Houston wearing our city clothes, but we’re willing to get our hands dirty. I tug on a rope and pull up the cage made of PVC pipe and netting. Dozens of crabs crawl around and on top of each other. Then we fish them out with a net and dump them in piles into the ice chest. Some are harder to catch than others and cling to the netting with their claws tightly clasped. We want to show our family we can retrieve the crabs, since they believe we are too refined and forget where we come from.

This is the first time we’ve been here since Pawpaw died, and his absence is acutely felt. I can see him standing on the dock, casting a line. I can see him sitting in a chair at the bottom of the hill looking out at the water. I can see him pulling up the crab traps from the muddy river bed and shaking them to reveal his catch. I can see him rinsing the bodies at the cleaning station and throwing them into the ice chest for Mawmaw to boil and fry for us.

But I can’t see him. Because he isn’t here. I see my Uncle Kevin, whose face has weathered into a similar shape as Pawpaw’s. I see my mom, her bald head swiveling around and only seeing grief. For her father, for herself. She is wearing a breast cancer t-shirt with the word fighter repeated five times and a backwards baseball hat. She takes a swig of beer and a drag from her cigarette. Me and Britney and Mawmaw and Uncle Kevin and my mom sit around the table and peel crabs. It is a beautiful day. The water is quiet and calm. The crabs are fresh and full. But something is missing. We are naked, stripped of our carapaces.

Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus), 2014, a Cyanotype print by Alexis Doshas. Courtesy the artist

My mom preferred boiled crabs to fried. She liked crab claws best. She cracked them open and tore the meat out. She liked all kinds of crab, not just our local delicacy. She liked king crab and Dungeness, which she rarely got to enjoy. Sometimes, she brought home crab claws from the grocery store and made herself a surf and turf with steak. At Joe’s Crab Shack, she ordered claws of different kinds and dipped them in butter. She ate crabs freshly boiled or cold, leftover the next day. She loved crab cakes and ordered them any time they were on the menu, no matter the price. Champagne taste on a beer budget, she called it.

Her favorite crab cakes were from Luna Bar and Grill in Lake Charles. We loved to brunch here on the back patio in the summer and watch the Mardi Gras parades pass by out the window in the spring. Two months before my mom died, Britney and I took her to Luna. She needed to walk with a cane but was still able to get out and about. The crab cakes were not on the menu anymore, but we ordered an appetizer: the intergalactic crab dip. It was melty and creamy and cheesy and full of sweet crabmeat. We ordered cocktails, which my mom rarely drank. This one had smoke wafting up from the ice. She showed off her new manicure, light pink nails with dark pink breast cancer ribbons swooped onto her ring fingers. After eating, we walked around downtown, ducking into antique shops and flipping through dusty records she played as a teenager. It was a wonderful day. She stopped a few times to catch her breath, and we took photos against an exposed brick wall. In one, we are leaning into each other, our foreheads touching and eyes closed, a subtle smile on each of our faces. They are some of my favorite pictures of us together. I didn’t realize she would be dead so soon after that. I never could have imagined her cancer would progress so much in two months.

Blue crabs molt. They shed their exoskeletons for larger, stronger armor. They do this up to twenty-five times over the course of their lives. This is how they grow. By the end of her illness, my mother was a carcass. Her skin stretched tautly over her bones. I could see her skull, her sunken-in cheeks. She had no shell to protect her. Nothing to stop the rapid rate of decay. Her body was failing, and she looked thirty years older than the last time I’d seen her. She was a skeleton. A thin, fragile thing held up by bones.

Blue crabs are bottom feeders. They eat plants, small fish, and bivalves, along with the dead or decaying flesh of other animals. They feed off of death. They eat the wastes of the water.

It’s gross to think about what we’re eating when we’re eating crabs. But that’s the way the world works. They eat dead things. We eat them. They die. We die.

I think of my mother when I see crabs. I think of my grandfather when I eat crabs. I think of them both swimming in space, a vast blue ocean of stars. My mom said I learned to crawl like a crab. Backwards and sideways. And it feels like I’ve been moving through life that way ever since, cudgeled by grief. I dissociate when I’m teaching classes, push the thoughts to the back of my mind then spontaneously cry on the bus ride home or in the middle of the aisle at Trader Joe’s. For a year after my mother’s death, I had no hope for the future, no plans. I was simply surviving. One day at a time.

When crabs are trapped in a bucket, they prevent each other from escaping. They claw at and climb over the other struggling bodies. They ensure their own demise. I could let these losses consume me, swallow me whole. I could reach for the top of the bucket and constantly pull myself back down. But I won’t. I can’t. I will have to grow a shell, a carapace of my own. But right now, I am a soft, fleshy underbelly, open for hurt.

This essay was published with support from The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.