Leavin’ a Trace

By Jaydra Johnson

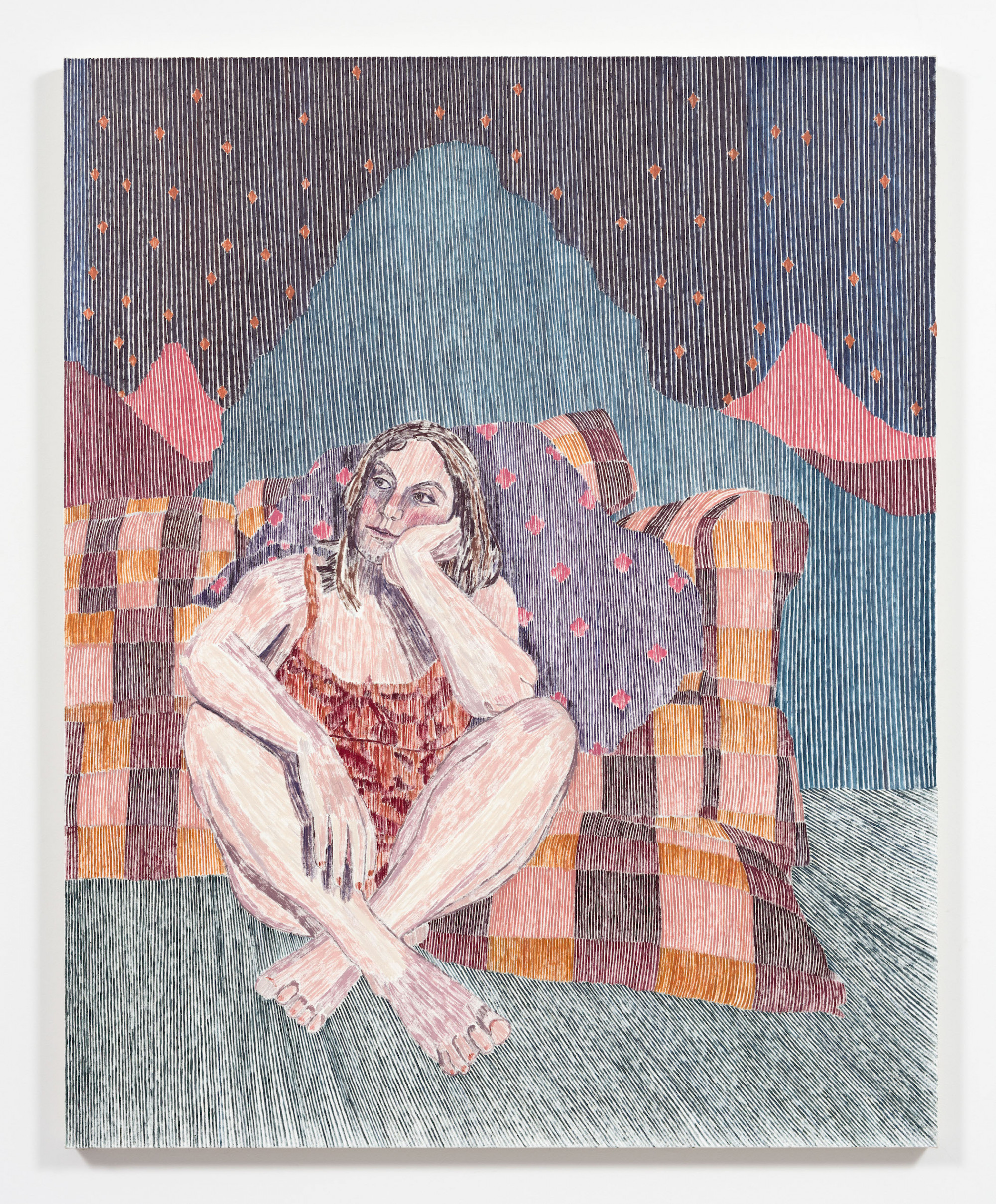

Stargazer, 2022, oil on canvas by Brittany Miller. Courtesy the artist and Steve Turner

C R A Z Y

I was cooling out in my bedroom. It was 1997, and I was nine years old. I hated my fifth-grade class in our new town—a gutted gravel pit of a place where the grocery store smelled like overripe apples and aging meat. The fog was thicker and wetter here, the kids paler and flimsier. They booed and hollered like little ghosts in the mist of the side streets, the parks. My stomach was sensitive to smells, to scenery, to sensation, to sound. I was not having a good time out there, but in the attic of my step-aunt and -uncle’s house, with the familiar rain on the roof, I could be soothed by the undulating smooth of TLC’s CrazySexyCool.

My stomachache made me pull my knees to my chest as I sat on the floor. This room was my escape while my younger brother was at school or sleeping or watching cartoons in the attic’s other room, not begging to play Sega on the solid state in the corner. We were a hard-luck family—my stepdad, my mom, my brother, and me—living for a while on our kin’s goodwill in what space they could spare in their modest house. The other room was where we slept, all four of us on two mattresses with no frames. The TV was always on. My mom was pregnant. I had the blues.

My boom box was black. When I pushed a button, its mouth opened. I put the CD in, closed the lid, and pressed play. I waited for the laser to scan the surface of the disc, to do its magic. I held my breath until I heard the drumbeat, the soul-sounds of synthetic horns, the wet wah of something guitar-ish. the album had already been out for three years, but I still listened to it every day.

I didn’t know too much about sexy or cool, but crazy was all around me in the trailer parks, the meth labs, the fast-food joints. Crazy was copper pipe reclamation rituals by moonlight, half brothers and informally adopted sisters, domestic disputes as daily facts, a six-pack of Budweiser, and showing face at Sunday church despite a week of sin. I heard it when T-Boz said, “I was chillin’ with my Kool-Aid / Did not want to par-ti-ci-pate / In no silly conversations.” I got Kool-Aid. I got not wanting to par-ti-ci-pate. I got that relationships could be silly or cruel.

With my CD player on and the door closed, I could daydream, pretend to be solo, elsewhere, older, and different. I could be deep in the borrowed cool of the music. The “Intro-Lude” came and went, and then T-Boz sang, “The twenty second of loneliness / And we’ve been through so many things.” I could relate. In many ways, I already felt old and weary of a world that seemed to want so many of us jailed, drugged, or otherwise dead-ended.

Willamette Valley, Oregon, in the ’90s and early aughts was a fractured land. New bans on logging slowed the destruction of the fir and pine forests, which was great news for the animals, the rivers, the lakes, and the waterfalls. But the news wasn’t as great for the people. Like in rust belt cities without their mines and factories, mass unemployment followed the end of timber, which led to a kind of necrosis. Decay reigned. Moss grew up through all the cracks. Everything that wasn’t green turned gray and black. Red devil lye and drugstore cold medicine became crystal became an epidemic. Me and mine got battered like everyone. Hence, the attic.

I wished I could “decide to say / Goodbye, goodbye” to this whole rotten life and start over. I desperately wanted to be “like peace in a groove / On a Sunday afternoon” or any afternoon, but I was not. I was depressed and poor and lonely.

I couldn’t have dreamed of the life I have now, “deep in a cool”—a room of my own in New York, an art practice, an office (albeit shared) at the college where I teach, my name printed in magazines, my own collection of pleather pants and baggy tops and men’s underwear, a crew of talented friends—because I had never seen anything like it. I had never been to a concert or a museum or a club or a gallery or a college campus or even a city. To get here, I had to let myself go crazy in the way that artists often do. At seventeen, I ran away from the heartache of home toward the biggest town that felt possible: Portland, Oregon, where I would spend the next fifteen years struggling to earn a living, get sober, graduate from college, and figure out who I was. At thirty-one, I went crazy again, escaping my comfortable life as an English teacher and part-time poet to chase down a faster, riskier creative life that I never thought someone like me could have. I made it to New York City, but I’ve never been able to outrun that little girl in the attic with an unmendable ache for something she can’t put into words, who needs other people to show her how to have hope in a hopeless world full of magnificent suffering. I never would have made it here without a trio of Black women in Atlanta who showed me a way I could be in a context that was anything but bubblegum pop and California dreams.

S E X Y

When Chilli and T-Boz sang, “I need someone who understands / I'm a woman, a real woman / I know just what I want, I know just who I am,” I smiled and held the plastic CD case in my lap, studying their faces. They emerged through the crimson fog from its hot center. Left Eye, without her signature under-eye black slash, faded into Chilli, pigtailed and pretty. Then came T-Boz, with that impossibly cool, bleached-out A-line haircut. They were affirmatively sexy, not passively sexualized. Hot for themselves. They were artists, self-possessed and serious, but not too serious. They were beautiful, sure, but beauty was not what I loved them for. I loved them because they were smart and brave and strange when they sang about life lived at the edge of risk and safety. I loved them because they could crush without being crushed, and for the way they were styled to a T.

The look was flawless. They wore baggy, boyish pants, boxer briefs, denim overalls, tent-sized flannels, loud hats, wild updos, face paint, puffy jackets, coordinated crop tops, sports jerseys, bras-as-shirts, gothy studded tanks, platform boots, punk-patched denim, shiny everything, and color galore. They made every look scream sex, but safe sex, cool sex, girl-wearing-a-backwards-hat-and-combat-boots sex. Whatever that was, it was new to me. The look came across as having little to do with intercourse and everything to do with confidence and volcanic creativity. I wasn’t having sex at nine years old, nor was I very interested in it, but I was fascinated by women who had style that broke every rule that seemed to govern self-expression for my small-town teachers, my and my friends’ mothers, and even the actresses on network TV. Kids at my school made fun of me for wearing boys’ clothes. TLC got famous for it.

My obsession with TLC began with “Waterfalls,” which was my favorite video when it came out like a cannonball and then arced long and high on the charts from ’95 and into ’96. I never tired of it, even though it was all over MTV and the pop radio station, even though the album spun inside my boom box for half of every afternoon, often with “Waterfalls” on repeat. When the video begins, the trio oozes up from the water like sexy specters, animated glistening goo girls gone wild (yet, as the song suggests, not too wild). Then, just as quickly, the glimmer of them becomes flesh and half-wet, all-hot outfits performing simple, synchronized dance moves. The video proceeds through sepia-toned, socially conscious scenes about drug trafficking and safe sex, returning to the opening wide shot of the three singing on endless, waveless water.

“Don’t go chasing waterfalls / Please stick to the rivers and the lakes that you’re used to / I know that you’re gonna have it your way or nothing at all / But I think you’re moving too fast.” I tried to imagine how I could be good, chase down the right waters, take the right risks. At nine, this was all speculation, vague fantasy and fear colored by the ways I’d already seen people fall. I didn’t understand the song exactly, but it sounded prophetic of what was to come for me.

Sirens were half-woman, half-bird babes in Greek mythology. One of the Muses speculated they were the daughters of the sea god Phorcys or of the river god Achelous. Who were TLC’s fathers? I would’ve believed they simply materialized out of sea or river, as they did in “Waterfalls.” Divine-born Sirens have been depicted as birds with the heads of human women or, in reverse, as women, sometimes winged, with legs like a bird’s. TLC didn’t have literal wings, but they seemed to fly high above my little life, dipping down from the sky on sound waves to kiss me on the cheek.

But I didn’t know about Sirens like I didn’t know about sex. To me then, T-Boz, Chilli, and Left Eye were real-life mermaids emerging from the water, but not like the fair, fawning Ariel of my Disney-laced childhood. They were Black and brown and beautiful, bad and bougie, each wrapped in her own diaphanous, iridescent cross between saris and JNCOs, grooving to a song of caution, grief, and careful optimism—an optimism I desperately needed, a caution and grief I lived.

Forty-odd years before TLC as a group was born in Atlanta, my maternal grandma, Nana Vickie, was born in rural Georgia. I grew up listening to stories about the citrus trees, cockroaches big as a baby’s foot, and great-grandpa Jack, a brutal man with a quick shotgun and beefy fists. He’d blast ya in the eye. No notice. “If ’ee’s got a bad temper, run. Don’t you never let a man hit on you,” I remember my elders saying. In their lore, men were power-hungry Poseidons who ruled with bad moods and bloodshed, and I had seen enough to believe that was true. I loved how the girls of TLC, despite their sappier songs, seemed to operate in a different story. They cheated on their boyfriends (“Creep”). They fell for pick-up lines when they felt like it (“Diggin’ on You”), they had sex when they felt like it (“Red Light Special” et al.), and they turned sex into a joke about taking a shit when they felt like it (“Sexy (Interlude)”). But later, I would learn that they, too, lived in the shadows of their own Poseidons, that the contract they worked under left them bankrupt at the height of their careers, and that many men had treated them badly. Here are just two allegations of such behavior: Left Eye was reportedly battered by her boyfriend Andre Rison, then a star player for the Atlanta Falcons; and per a 1997 interview she did with MTV, Chilli’s romantic partner, producer Dallas Austin, once held several of the group’s tracks hostage to the tune of $4.2 million. Discovering that many beloved songs on CrazySexyCool, including “Creep,” “Red Light Special,” and “Waterfalls,” were written by men (Dallas Austin, Babyface, and Organized Noize among them, though Left Eye shares writing credit on several songs) forced me to look anew at what I’d previously held dear as anthems of realness. Was the CrazySexyCool media package actually the antithesis of authentic feminine power, little more than a puppet show and a ploy for men to make money? Maybe. But I have to believe that TLC, despite this, felt bold and free up there singing, even if what they were performing was yet a simulacrum of their shared dream.

Even so, it breaks my heart to know how hard the world and a few of its men failed them and with how much intention. I love them more for the ways they struggled to regain control of their art and spoke the truth about their experiences, and for the way they kept making music amid the treachery and heartbreak. I, too, have a creative life that creates more bills than it pays. I, too, took on debt to pursue an American dream, though mine is in the form of student loans, which are far less sexy than million-dollar videos and sold-out tours. I, too, trusted a man in the South who, though he never hit me or exploited me for money, left me so heartbroken that I couldn’t get out of bed for weeks. I had promised myself that I “what’nt gon’ be nobody’s fool,” but I was. None of us want to be the sucker, left “longing for the days of yesterday,” but sometimes we are.

When I listen to “Waterfalls” today, I still hear a lament for loved ones lost and a call to hold on amid personal crises, but I also hear an argument that to fall victim to social problems, particularly ones that hit the Black community hardest—gun violence, AIDS, drug addiction—is a personal choice, an assertion I can’t get behind (“life is about choices is what / assholes with the best choices say,” the poet CAConrad writes). A more generous reading would be that “Waterfalls” is a spiritually inflected rallying cry for folks to remember their power in the face of worldly brutality. TLC would have their audience focus on building a safe, simple life (and more specifically, strong Black communities) rather than chasing desire or status. So maybe it was never about dreams at all. Today, I can see that it was never a song for a nine-year-old white girl in Nowheresville. What’s more, I’m not even sure I still like it. And yet.

What makes a song carry us? What makes a song make us whole even when we don’t understand all the words?

C O O L

I couldn’t get down with the Spice Girls like my classmates. At that one sleepover, when every girl chose their British girl band avatar, I did my best to disappear into the couch cushions. Against my will, they decided I was Sporty, I guess because I seemed dykey—my talent on the field could not possibly have earned me the moniker. I agreed, but only because I didn’t need any more help at being a pariah and because Sporty did dress kinda cool, kinda like a TLC member. I sang along to the songs when abstaining would’ve made me look like even more of a bummer.

“If you wanna b my lovah, you gotta get with my friends. Make it last forever. Friendship never ends,” I sang along, but it all felt fake. The Spice Girls and their songs were flimsy cardboard cutouts. To me, the Girls looked like animatronic dolls, a product from the get, an illusion, a lie.

TLC, on the other hand, inhabited an Earth, my Earth, a place of rivers and waterfalls and sex workers and mothers and guns and HIV and low self-esteem and rainbows and Fourth of July cookouts. That realness made me feel seen, not just in the present, but in the future. In being described, written, mythologized, I could exist beyond the attic, the sloughs, the lunch line, the rain.

The best part of “Waterfalls” comes after the second verse. The trio dematerializes back into CGI water women and Left Eye launches into her rap, the one I memorized before I even got the CD by waiting next to the radio for the song to come on 104.7 KDUK. She sings, “I seen a rainbow yesterday / But too many storms have come and gone / Leavin’ a trace of not one God-given ray / Is it because my life is ten shades of gray?” My gray life. The storms. Prayers. Flat tires. Rainbows. Could things change? “My only bleedin’ hope / Is for the folk who can’t cope / Wit’ such an endurin’ pain / That it keeps ’em in the pourin’ rain.” Rain on rain. An inability to cope. People around me moving too fast toward things that weren’t good for them. I believed that dreams were “hopeless aspirations / In hopes of comin’ true” because I heard aspiration after hopeless aspiration pouring from the lips of my elders, and yet nobody ever seemed to get a wish-come-true. But I had to believe in a blue sky someday. I had to believe in weather systems, accumulation then clearing. A washing away.

While the others had their Spice Girl, I had Left Eye. My tattooed hero. Black line like a quarterback’s under that eponymous eye, a warning. Cute but tough. Outside the world of “Waterfalls,” she was an icon in floppy hats, sculptural jackets, and the longest shirts of the three. She was sort of a Dennis Rodman figure (another obsession of mine at that age), bending gender gently into a star shape. She was a hard girl and a soft boy in one body. Left Eye possessed a toughness and confidence I envied, that I still envy, that I needed and need.

Lisa Nicole Lopes, who shares a middle name with me, was born in North Philly in 1971 to an abusive alcoholic father and a mother I can’t find any information about. Lopes’s family moved often during her childhood, as did mine, and her parents got divorced, as did mine, and she was thrust into the role of caretaker for her younger siblings, as was I. “The amount of change that I went through would probably drive a normal person nuts,” she told Rolling Stone. I once counted that I had moved forty times before my twenty-fifth birthday.

Lopes’s Wikipedia entry exalts her as the creative heavy-lifter of the trio, asserting that she earned “more co-writing credits than the other members” and also “designed some of their outfits and the stage for [the] ‘Fan Mail Tour,’” but I can’t find any external sources to corroborate this. However, there are plenty of sources that talk about the mansion, the mansion belonging to her boyfriend Andre Rison—though as can be the case with celebrity gossip, the details differ from one report to the next. One morning in 1994, Left Eye—possibly drunk, perhaps pushed to the brink by the knock-down drag-outs, maybe mad at being left off the gift list when Rison went on a shopping spree—set fire to a pair of his beloved sneakers in the bathtub. The flames became a frenzied blaze, burning the mansion beyond salvation. She did not escape unscathed. She was charged with felony arson and criminal damage to property, placed on probation, fined, and ordered to complete an alcohol treatment program. But if she felt shame or self-doubt over the incident, she didn’t show it. “I was just trying to barbecue his tennis shoes,” Lopes would later say. Even as a little kid, I know I would’ve thought that was cool (I still do).

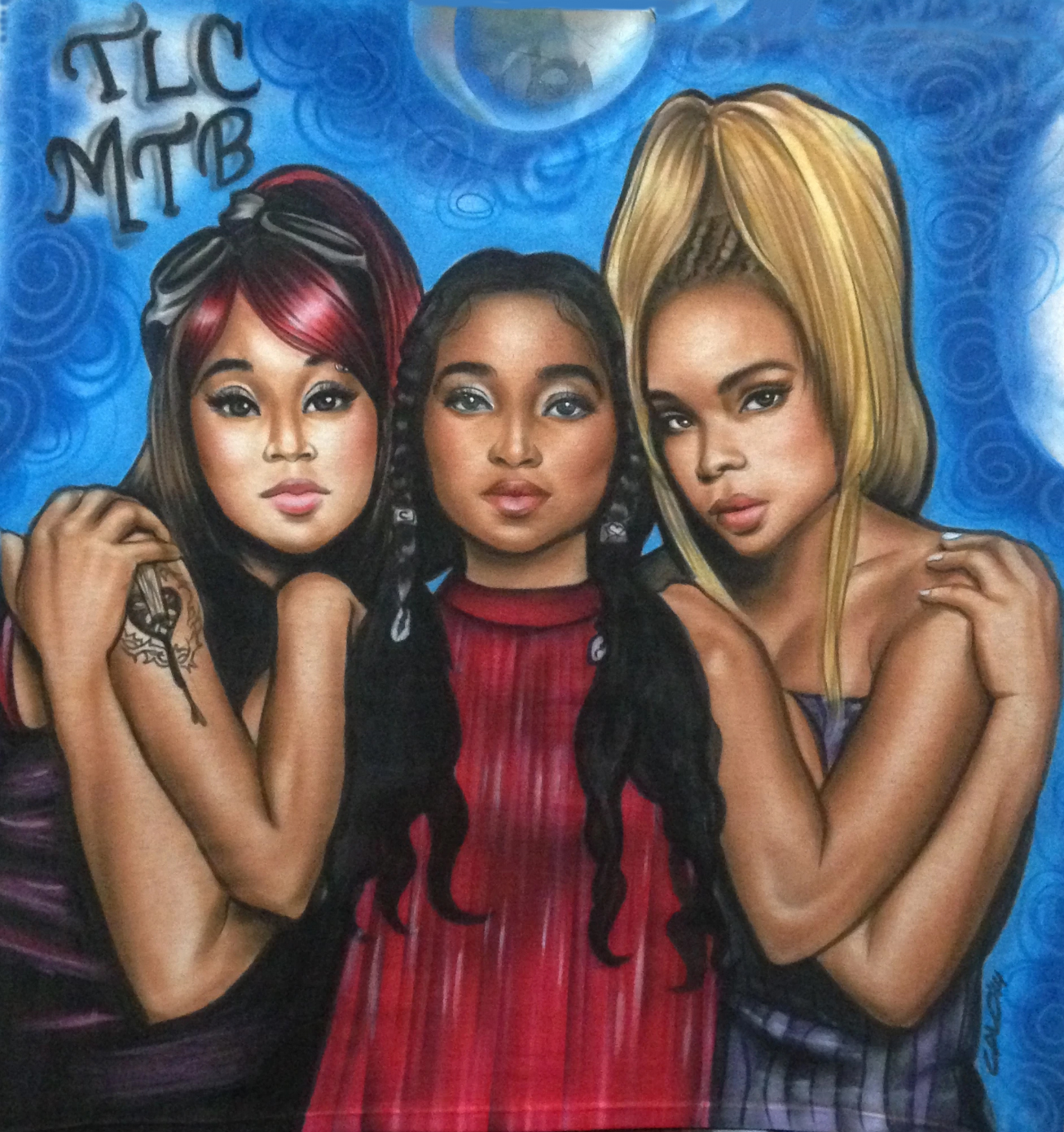

Airbrushed portrait of TLC, 2021, by Carlos Ampudia of Graffiti Pop Events. Courtesy the artist and Graffiti Pop Events

I had learned early on to scorn men who slapped, sat on, or otherwise scrapped with their girls no matter why they did it. Left Eye was the good kind of bad, or the bad kind of good. CrazyandSexyandCool.

That Left Eye struggled with alcoholism, as I later would, was unknown to me then, but maybe I saw a sort of sister there too. A familiar haunt behind the eyes. She treated her disease in her private ways, including with intense meditation and yoga practices, which I would end up using to treat my own drinking problem. It was on a spiritual retreat in Honduras that Left Eye died in a car accident. She was thirty.

I am now thirty-five and maybe, like Lopes, I shouldn’t be alive. Between my addictions, an eating disorder, a couple of psychiatric diagnoses, and all the other waterfalls I chased or that chased me, I have sometimes had to fight to stay and have needed someone to remind me why I should try. My meditation teacher says that if life’s two guarantees are suffering and change, we need a way to exist that doesn’t add to the grief. CrazySexyCool, then, is my mantra, a credo, a trade of light for gravity, a rubric by which I can gauge how right I am living. Perhaps that’s why the last track, “Sumthin’ Wicked This Way Comes,” the other song on which Left Eye gets in a solid rap, this one more cryptic and poetic, is my current favorite. “I just don’t understand / The ways of the world today,” the trio sings. “Sometimes I feel like there’s nothing to live for.” I can relate. Left Eye goes on, narrating my own self-criticism and fear: “I keep misfocusin’ my needs... / My mishap is the fact that I’m destined to snap.” But the verse ends on a painterly note that gestures toward mastery and a cool self-assuredness: “If I’m late, it’s ’cause I’m endin’ my day / Just when the sun shines / And still gently advising the arisin’ of the moon / As it rolls around into my soundproof dimension.”

I don’t think I knew at nine years old that Left Eye burned down her boyfriend’s house, but I know that now, and I can also see how I saw myself in her as a young, sad girl who wanted to be brave and bold, who wanted to sing, who the clouds hung over, who wanted to move but not too fast, who wanted to be that perfect combo of good and bad, who wanted style, and I want to say to all three, but especially to Lisa, apple of my early eye, beacon of much that I still hope to be, Thank you for making a whole world for me. RIP.