Made for TV

On Polly and Debbie Allen's directorial savvy

By Jessica Lynne

Debbie Allen, circa 1983 © Harry Langdon/Getty Images

Harrington, Alabama, the fictional setting of Polly, is a quaint and genteel town. It is the kind of place where, because everyone knows everyone, secrets hardly exist and it is difficult to make trouble, as you are bound to run into someone who knows your people at the grocer’s or the general store or while out taking a casual walk. In Harrington, the week’s agenda might be determined by the tone and mood of a Sunday service or a community meeting organized to determine the curriculum taught to children at the local orphanage. Harrington is a place where Black folks live on one side of the creek and white folks live on the other. And Harrington is most certainly a world away from the beboppin’ Detroit that young Polly Whittier leaves after her parents die in a tragic car accident.

Such are the scenes that propel the 1989 made-for-television musical Polly, directed by the multi-hyphenate Debbie Allen. As one might suspect, Allen’s Polly takes as its source Eleanor H. Porter’s novel Pollyanna, in which an orphaned Polly is sent to live with her conservative aunt Polly Harrington in Vermont. Naïve and full of life, Polly has a cheerful attitude that infects all those around her—even her rigid aunt, who begins to soften toward the child as the residents of the town join in on Polly’s “glad game” that encourages them to find new perspectives for their blues. Polly’s buoyant spirit comes to serve her well when she is faced with a catastrophic physical accident herself.

Debbie Allen is perhaps most immediately recognized for her legendary career as a dancer, choreographer, and actress. One of her most widely known roles was the tough yet fabulous Lydia Grant in Fame, the movie and subsequent TV series that ran from 1980 to 1987. By 1989, however, the year Polly debuted on NBC, the Houston-born artist had also been directing for almost a decade.

When she accepted the role as Grant in Fame, Allen did so on one condition: that she would also be allowed to choreograph on the show. In a short video interview for the digital publication MadameNoire, Allen describes this negotiation as her pathway to directing. “Most of the directors didn’t know how to shoot dance,” she says. “So they would go home and I would shoot the numbers for them.” Allen would leave instructions for the male directors as to the most appropriate shots—a close-up here, a dolly shot there—to use for performance scenes, even as those same directors underestimated her knowledge and skill. One director “actually patted me on my butt,” Allen recounts in the interview, and told her not to “worry your little self about what the shots are.” By the end of that day, though, not only had Allen properly checked her colleague’s ignorance and harassment, she was shouting “action” and “cut” on set. Her training in dance, I might argue, is what first enables Allen to best understand the delicate balance of pace and narrative, as well as the relationship that performers have to space and sets (or settings) in order to tell a story.

Television, which has constituted the majority of Allen’s directorial oeuvre, is constrained by time differently than cinema. In her book Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America, Lynn Spigel argues that in the postwar era, as televisions entered homes in mass, networks structured daytime programming to meet the presumed leisure needs of their ideal audience: the housewife, “Mrs. Daytime Consumer.” TV execs thought that this figure—almost always read as white, straight, and middle to upper class—would be splitting her time between domestic chores and leisure moments throughout the day. Daytime television in particular was originally organized in a format that would allow for incorporating commercial breaks—with advertisers attuned to women as a vital new consumer base—and the ease of falling back into a show after breaks via the soap opera recap or the segmentation of the variety show. Spigel points out that, to maintain narrative threads in these female-focused stories, variety shows relied on “women editors” and “femcees.”

We can see Allen drawing on this convention in the 1989 made-for-television event The Debbie Allen Special, which she wrote, directed, choreographed, and produced. It is a humorous mélange of four separate stories in which four protagonists, all named Debbie, navigate the ins and outs of the entertainment industry. Debbie goes on a dance audition. Debbie meets with a theater critic on the opening night of her first Broadway play. Debbie, a washed-up actress, goes on a blind date. Debbie, a young actress on the verge of stardom, breaks up with her boyfriend. At the beginning of the program and before each vignette, Allen is a charismatic guide who introduces the dilemmas and conundrums of her characters while also playfully interacting with the featured co-stars: Phylicia Rashad (Allen’s sister), Whoopi Goldberg, Little Richard, Philip Michael Thomas, and Robert Guillaume. The special is a little sultry, over the top, and cheesy in a way that embodies the aesthetic characterizations of the era. But it is still remarkably engaging to watch this intergenerational cadre of Black entertainers (now regarded as industry legends) on the screen. I love it when, for example, an off-camera Allen playfully yells at Little Richard to “86” the singing before the vignette “On Broadway” cues up. Allen understands the wit needed to make her broadcast unique enough to hold viewers’ attention while she remains attuned to the particular rhythm of a broadcast.

Debbie Allen with the cast of Fame, 1982 © Gene Trindl / mptvimages.com

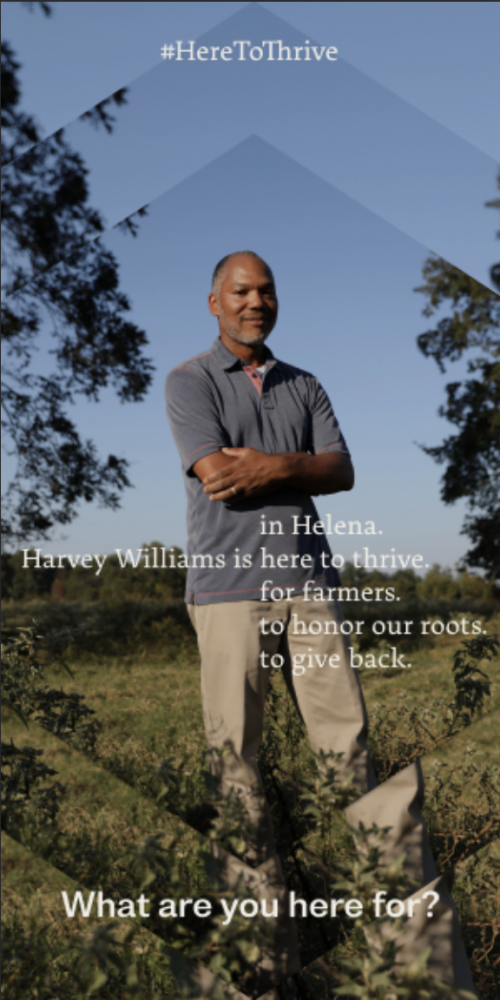

Debbie Allen (in jumpsuit) directing Polly © 1989 Walt Disney Company

Her time as director on The Cosby Show spin-off A Different World saved the series entirely and catapulted it into now canonical status alongside many other Black television shows of the late 1980s and early ’90s, including Living Single, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and Martin. A Different World tells the story of students and professors at Hillman, a fictional historically Black college set in Virginia. Allen drew from the complexity of her own undergraduate experience at Howard University to breathe new life into a show that she considered to have been mostly “so silly” in its first season, as she said in a 1992 New York Times profile. Instead, as both director and executive producer, she brought a measured gravitas to the depictions of these young people by working with the writers and actors to raise the political stakes of the show’s storytelling, infusing more elements of HBCU culture such as Greek life into the DNA of the show, and even adding new characters to the cast. Allen became hands-on in her tenure, with a self-imposed edict: “make it relevant, make it cultural, and go deeper with the characters to see what’s going on behind the masks.” The result is a show that illuminates a less familiar collegiate HBCU experience for a mainstream (read: white) audience while illustrating a universal sense of angst, pleasure, and maturation that accompanies college life.

Indeed, though television’s emphasis on housewives as its primary audience had waned as it established itself as the dominant medium of popular culture, its relationship to whiteness and middle-classness did not. Allen’s edict, then, about her time at A Different World takes on a new resonance when applied to the breadth of her entire career. Behind the camera she is confident, assured, self-possessed, and careful not to overwork her material. She is also considerate of how to depict the complexity of Black life on screen, drawing from many lineages of Black art—such as the comedic, theater, and dance traditions embodied by the co-stars of her special—and taking on projects that feature an intergenerational cast of Black actors, dancers, and performers. This also functions as a nod to Allen’s own creative palette. For example, the iconic Butterfly McQueen, whose own career, like Allen’s, began in dance and who is best known as Prissy in Gone With the Wind, appears in Polly as Miss Priss, the last role of the actress’s life.

Phylicia Rashad with director Debbie Allen, 1990 © Walt Disney Television. Courtesy Everett Collection

In Allen’s Polly, mid-century Black life takes center stage, as the original Vermont setting of the book becomes Harrington, Alabama, the town named for its most important benefactor, the elder Polly. Played by Phylicia Rashad, Polly Harrington has become the steward of the town’s mill in the wake of her father’s death. Cold, distant, and uppity, Harrington is a Black Southerner whose social codes and mores reflect a world of means. Her money buys her the ability to dictate Reverend Gillis’s (Larry Riley) weekly sermons at the church. It keeps most of the town’s residents employed at her mill, casting their economic fates in her hands. It threatens the successful run of the first bazaar organized in support of the orphanage when those very residents decide to refuse the yoke of Harrington’s checkbook. But, as we learn, Harrington is simply a lonely woman after heartbreak and has steeled herself up as a defense.

Of course, the town of Harrington is nothing like the big city that Polly Whittier, played by Keshia Knight Pulliam (who was at the time Rashad’s co-star on The Cosby Show), was born into. As such, her curiosity about her new surroundings and the adult now responsible for her care is endless. Allen uses the relationship between the two Pollys as an opportunity to subtly point to the sociopolitical. Her adaptation is set toward the end of the second wave of the Great Migration, which saw many Black Southerners leaving their homes for the urban centers of Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, and Detroit. Young Polly’s parents, we are led to conclude, sojourned from Alabama to Michigan as part of this wave.

In the context of the musical, she also represents the nuanced differences of postwar, working-class Black urbanity and a stable, upper-class Southern life. In a scene I love, Polly is sent to the town’s dress store to purchase “proper” attire for a child of her new station. Classical music oozes from the speakers as Polly, her aunt, and her aunt’s assistant, Nancy (Vanessa Bell Calloway), enter the shop. As soon as Harrington departs to attend tea and a meeting, Polly asks Nancy if the radio has “any Detroit music.” When the young girl marches over to the radio and changes the station, the cast breaks out into a musical number in the style of a 1950s Motown girl group. Allen calls forth the significance of the emergence of Motown sounds within American culture, effectively integrating popular music with its major crossover success, while also using music to demarcate the supposed lines of comportment that Polly’s aunt aspires she attend and which Polly crosses repeatedly. Here again, Allen’s gift as a choreographer who directs shines through a series of close-ups and medium shots to emphasize movement, capture facial expressions, and show off Polly’s fancy new clothes.

Much like Porter’s protagonist, Allen’s Polly is a voice of levity, unexpected wisdom, and youthful clarity, and she becomes the moral engine for the musical. At the same time, the film remains virtuous without offering a hackneyed display of Black Southern vernacular or the intimacies of small-town living. Language and accents are not deployed as hyperbolic depictions of an imagined Southern scape that is “backwards,” a trope so frequently relied on in Hollywood. Nor is the town of Harrington devoid of the interracial conflict that would inevitably loom given the time period—even if the depiction of such strife is muted. Admittedly, Allen does play it safe in this regard, perhaps mindful of her television audience at the dawn of the 1990s and a forthcoming movement of multiculturalism. The realities of segregation do confound Polly, and her repeated questions about life on the “other” side of the creek—the ostensible territory of Ms. Snow (Celeste Holm), the older white woman who is as mysterious and wealthy as Ms. Harrington—serve to innocently question the utility of such a system.

But such relations are not the film’s center. In fact, Allen rarely visualizes for us any quotidian interactions between white and Black characters. When those moments do occur, they are pointed and declarative. Take, for instance, a scene at the film’s conclusion in which the town’s white doctor delivers an update about Polly’s injury from a fall. Harrington, ever dignified as she walks toward Polly’s doctor, rebukes him for referring to the child as a pickaninny. “Doctor, what we’ve got in that bed upstairs is one brave little girl who may grow up to be a beautiful young woman,” Harrington asserts. “And if she lives long enough, she might become a funny, delightful old lady, but she never was, nor will be in your lifetime or mine, nobody’s pickanniny.” She does not raise her voice and she does not shrink from this white man in front of her. The group that has come to see about Polly, including Reverend Gillis, Ms. Snow, and Nancy, spares no side-eye, and you know Allen, whose own childhood was marked partially by segregation, knows to hold steady on Rashad in this moment. A town divided is ultimately reconciled unto itself as young Polly ambles, in the film’s final scenes, across a rebuilt bridge to cut a ribbon that marks a new beginning and a reconnection.

This is most definitely a formulaic resolution, but I’d be lying if I said that this ending doesn’t satisfy me every time I watch it. Which is not to claim that I rewatch the film regularly—I don’t. But when I do, I’m always at ease. I couldn’t even describe to you the faint memories of my first viewing, many scenes echoing the lingerings of my own Southern childhood in church or surrounded by elders with rather prudish outlooks on life. What I do recall is coming to this film, a kid who loved television, after my childhood introductions to Fame and A Different World and remaining in awe of this woman who seemed to have a Midas touch with every story she told. Her method just worked: make it relevant, make it cultural, and go deeper with the characters to see what’s going on behind the masks.

Debbie Allen directing Stompin’ at the Savoy, 1992 © CBS. Courtesy Everett Collection

In that New York Times profile ahead of the CBS broadcast of her next made-for-television film Stompin’ at the Savoy (1992), the critic Jennifer Dunning positions Allen as a filmmaker on the cusp of her big break. Dunning reasons that Allen, then forty-two, had proven herself ready. “At a time when male black film directors are establishing themselves in Hollywood,” the journalist writes, “[Allen] is among the very few black women on the verge of breaking through as a director of a major studio film.” (John Singleton, Spike Lee, and Ernest Dickerson were the most notable of Allen’s male peers at the time.)

I do understand Dunning’s position here. The most natural next professional step would be a major studio film. At the same time, and maybe this is also the advantage of hindsight, I question what it meant, even then, to not understand the work that Allen had already done—an oeuvre that was becoming part of and shaping a definitive moment within Black popular culture—as anything other than a breakthrough.

“Black women were running television in the 1990s,” my friend and Columbia University film professor, Dr. Racquel Gates, reminded me over lunch one day. Alongside Allen at A Different World, Susan Fales-Hill was a lead producer and writer on the show. Yvette Lee Bowser, who also got a start on the Cosby Show spin-off, created her own production company, Sister Lee Productions, and went on to create the sitcom Living Single. Sara Finney-Johnson and Vida Spears were two of the three co-creators of Moesha. American television was changing exponentially in the last decade of the twentieth century, and Allen was most certainly one of the reasons why. That Polly’s success didn’t translate into a box office ticket for Allen as a director does not diminish the impact that would follow in its wake as television networks welcomed a wide array of Black stories on the airwaves. And Dunning’s stance that cinema would offer Allen her career high harkens back to the very gendered (and antiquated) assumptions that Spigel observes about the merits and functions of television as a vehicle for popular media.

In some corners of the internet today, Polly still has a committed following. I know this because talking about this film online years ago is the origin story of one of my own friendships. And Allen, who has gone on to direct shows like Girlfriends, That’s So Raven, Scandal, Insecure, and the never-ending Grey’s Anatomy, is beloved. Who among us did not dance along as she guided legions of Instagram followers through afternoons of choreographed routines during the most intense moments of the pandemic? I’d like to think that the film’s popularity endures because regardless of how much time has passed, so many of us have spent hours in front of a television, quietly influenced by Allen’s art—her gift—which is very much a love letter to Black folks near and far.