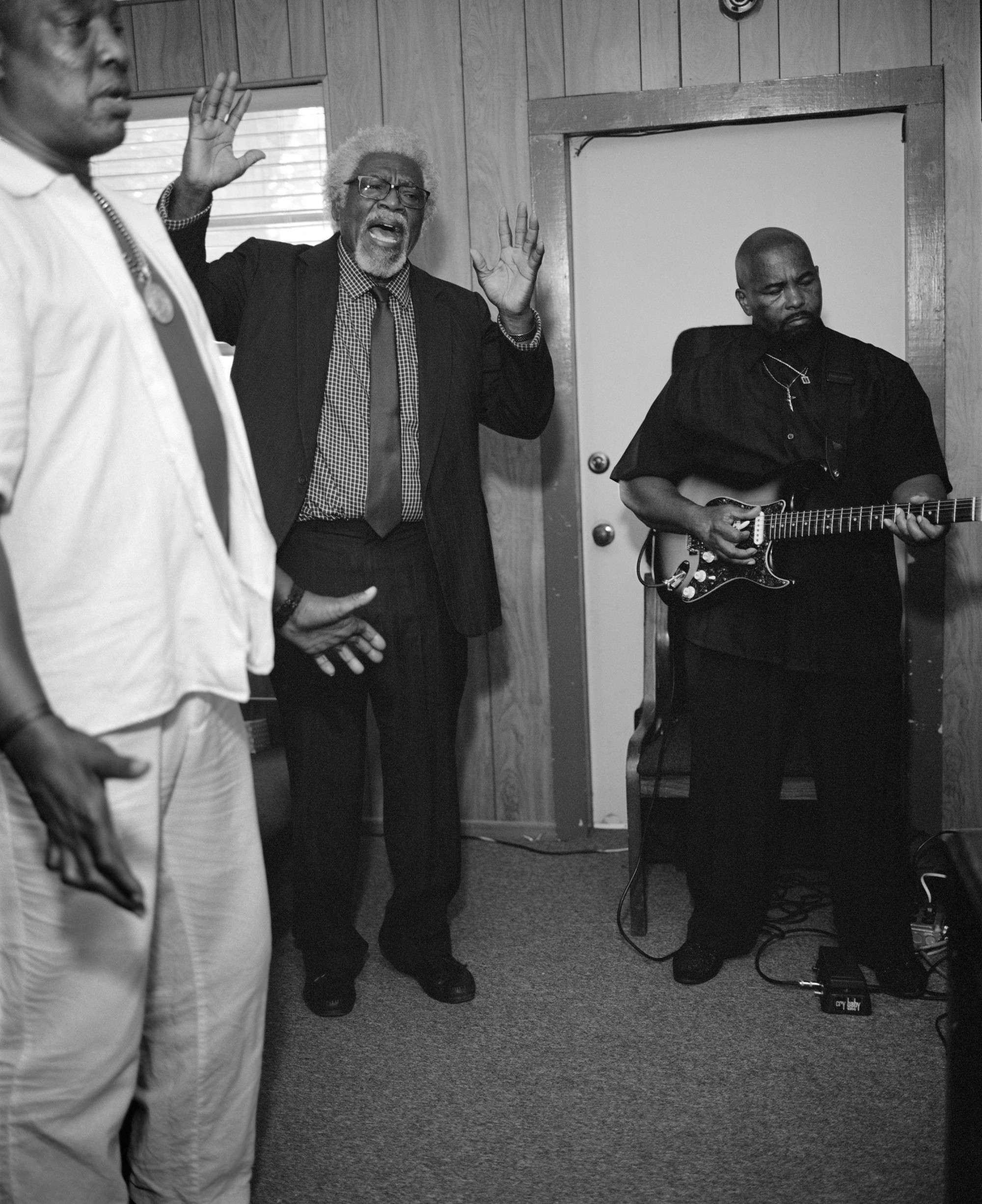

Faith Temple, Houston Texas 2023. All Photos © Rahim Fortune

The Intimate and the Public

On Les Blank and collaborative documentary

By Rahim Fortune

The melodic cry of the accordion, faces in the crowd entranced by the music, friends sharing a laugh, joy after a hard week of work or heartache. Smoke fills the room, drinks pour, the sound from the band swells in a small Louisiana juke joint. Hot Pepper, a 1973 film by Les Blank, chronicles the life of zydeco legend Clifton Chenier in his native South Louisiana.

I first encountered the work of Les Blank in my early twenties through the Criterion Collection, and I was mesmerized, gripped by Blank’s sense of composition, lighting, and color paired with gorgeous sequencing and juxtaposition within his editing. His ability to evoke deep feelings and human expression with modest means is a signature of his work. I began watching as many of his films as I could get my hands on. Spend It All, Always for Pleasure, and Dry Wood are a few of my favorites. The characters—brooding, complex, but optimistic—and idyllic landscapes represented in such stark color and detail enthralled me.

Blank worked as both a cinematographer and director across his body of work. His attentive intentionality only strengthened throughout his career as he went on to direct forty films over the course of five decades. Everything we see in his films comes directly from his own imagination and sensibilities, and his unique style carried him gracefully between subjects.

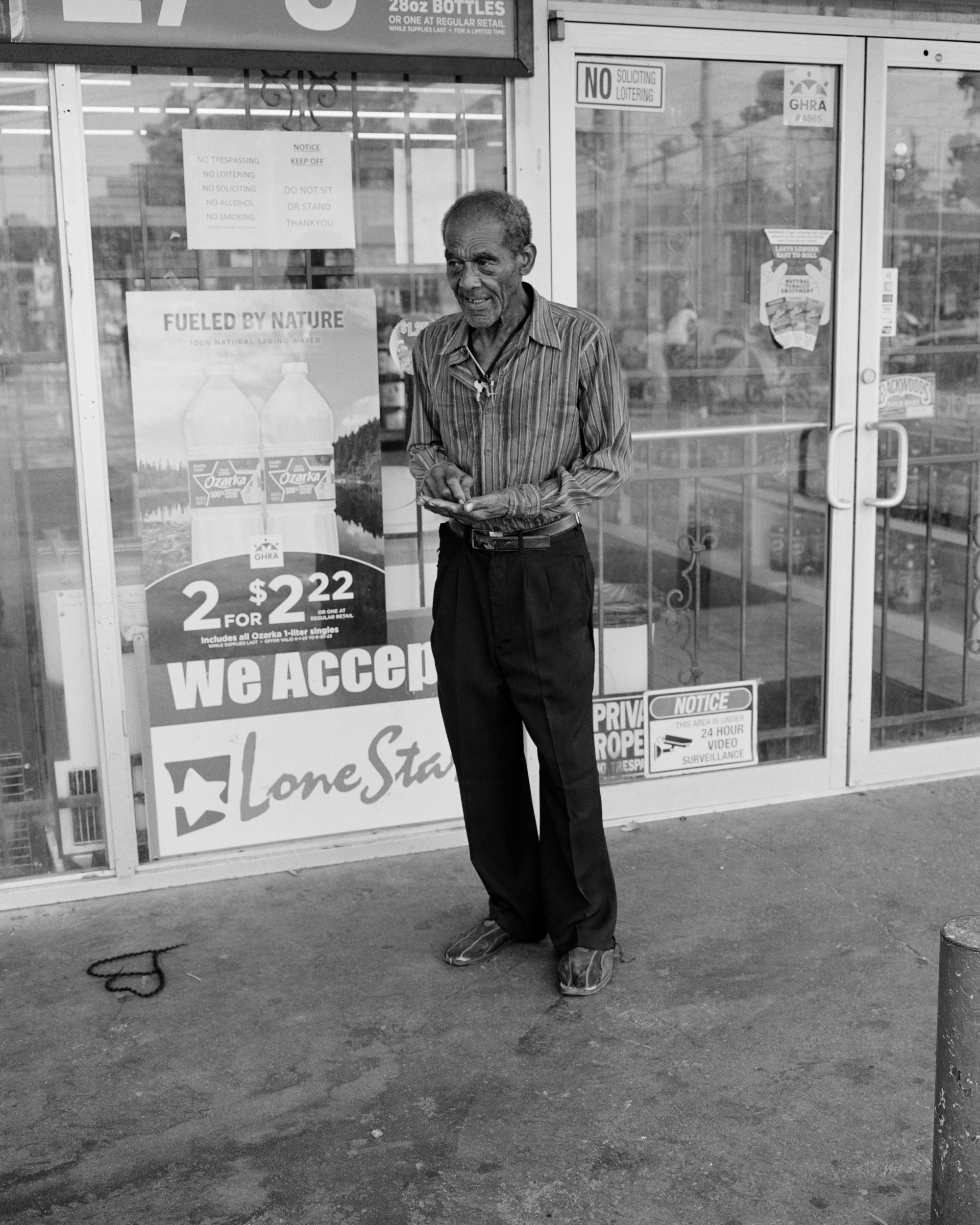

Willie Chapel, Austin Texas 2022

Grand Matron, Houston Texas 2023

Easter Sunday, Austin Texas 2023

Homecoming, Prairie View Texas 2022

In his work in the Seventies, he documented a range of subcultures, creating portraits of people and the landscapes they were fixed within. Shooting scenes of people crossing train tracks, juxtaposing figures in leisure and at work, and documenting musicians rehearsing, recording, or performing live, Blank used a zoom lens, tripod, and long shot durations in spaces such as barrooms, horse races, and cookouts. He would often move from vignette to vignette within one larger scene, capturing expressions, responses, and details of the scene to paint intimate pictures of the subjects represented. This approach allowed him, the creator, to fade into the background and not disturb the organic moments around him. By tracking wider scenes full of geographic indicators and eccentric characters, Blank gave viewers a full sense of setting; then he would employ the zoom lens to show details within that established space. This style of filming is similar to how one would naturally survey a room with the eye. In effect, the viewer feels involved in the action.

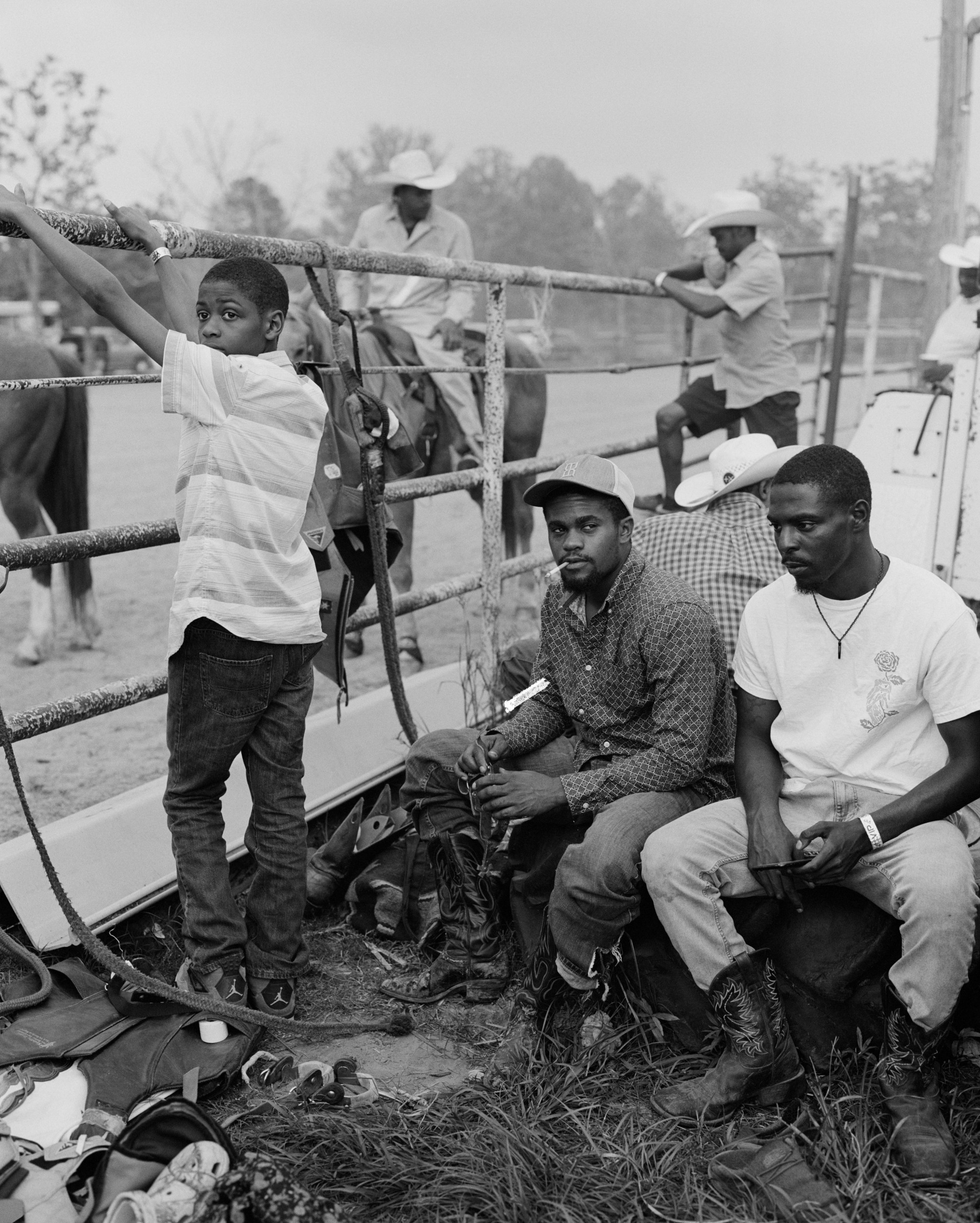

When I learned about Blank’s work, I was just beginning my journey as a photographer, still gaining influences and finding my voice. In 2016, I began making photographs that would ultimately become my first bodies of work. Drawing inspiration from my upbringing, from stories closely passed down from my grandparents, I took photos in Texas and Oklahoma of the towns and people I grew up among. The familiar would become my primary subject, focusing on daily life and social rituals in the South. With cinematographer Adé Randle, who has been a close friend for nearly a decade, I began attending parades, rodeos, and various regional events to connect with people and learn how to arrange my ideas and interactions with a camera. Inspired by conceptual art and documentary films, we began working to bring still and moving images together, creating installations that we showed across the country and internationally.

Randle and Fortune have sustained a close collaborative relationship that they bring into their photography practice. Still by Adé Randle

Randle and I have sustained a close collaborative relationship over the years and have spent countless hours traveling around Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana documenting Southern American culture. Our friendship plays a part in how we are able to connect with people—our relaxed demeanor, shared humor, and low-key way of communicating sets folks at ease as we approach them to make photographs. We connect with the people we encounter by communicating the importance of documenting their lives and fostering community.

Many of the regions and events we document intentionally parallel the work of Les Blank. In the late Sixties and Seventies when he was making his films in Louisiana and Texas, many of the cultural traditions uniquely associated with rural Southern communities were becoming marginal. As an automobile-driven, faster pace of life became the national standard, many small towns and subcultures fell from prominence in the wake of a more homogenous America. Customs practiced for generations were passed down less and less as communities assimilated to the mainstream to survive. Blank’s films live on as some of the most detailed accounts of these subcultures in the Southern Coastal Plains region of Texas and Louisiana.

Acres Homes, Houston Texas 2023

TrailRide, Cheek Texas 2023

Althea & X'ene Houston Texas 2023

Since first picking up a camera, I’ve always been interested in the fibers of American culture. The feelings I experienced when first seeing Hot Pepper are foundational. There is a simplicity of the viewing experience that I hope to convey in my own work, something that feels real. Capturing and then sharing special moments, like those seen in the regional events in Texas—full of triumph, pride, and excitement—leaves proof that we were here. This act captivated me when I began photographing, and I realized this was something I would be doing for a long time.

Though Blank and I come from our own unique viewpoints, backgrounds, and generations, I see an inherent overlap in the focus of our work. We share an interest in both the intimate and public lives of people, but also in the beauty and way our lives are connected to the landscape and nature in the American South. We are attuned to how these merge to create who we are, as people and communities. Working in such a personal manner and creating meaningful connections with people require a special set of skills that I’m still continually crafting and fumbling through.

The world is full of preconceived notions and apprehensions, and as creators, we must be mindful of our natural tendency to embellish. Documentary photography has a fraught history, as images captured have often stripped marginalized communities of their agency and ability to control their own narratives. This dates back to the Great Depression–era photographs of the Farm Security Administration, which are often considered the inception of American “documentary style.” Though I believe deeply in the power and beauty of photography as an art medium and means of documentation, the hierarchical dynamics imposed by the camera are embedded in the practice. How does one get at the truth of life using the tools of documentary? What does an objective view look like when every decision is dictated from the creator’s point of view? Is objectivity even possible? Les Blank’s films help answer these questions, as throughout his career he challenged the notions and limitations we put on ourselves as image makers. His work delivers on the promise of what is possible for art when it is made in the spirit of collaboration, led by genuine curiosity and an open heart.

Les Blank

Blank's work evokes deep feelings and human expression with modest means. His sense of composition, lighting, and color informs Fortune's photography.

Hot Pepper

Always for Pleasure

Spend It All

Dry Wood

Stills courtesy the Criterion Collection