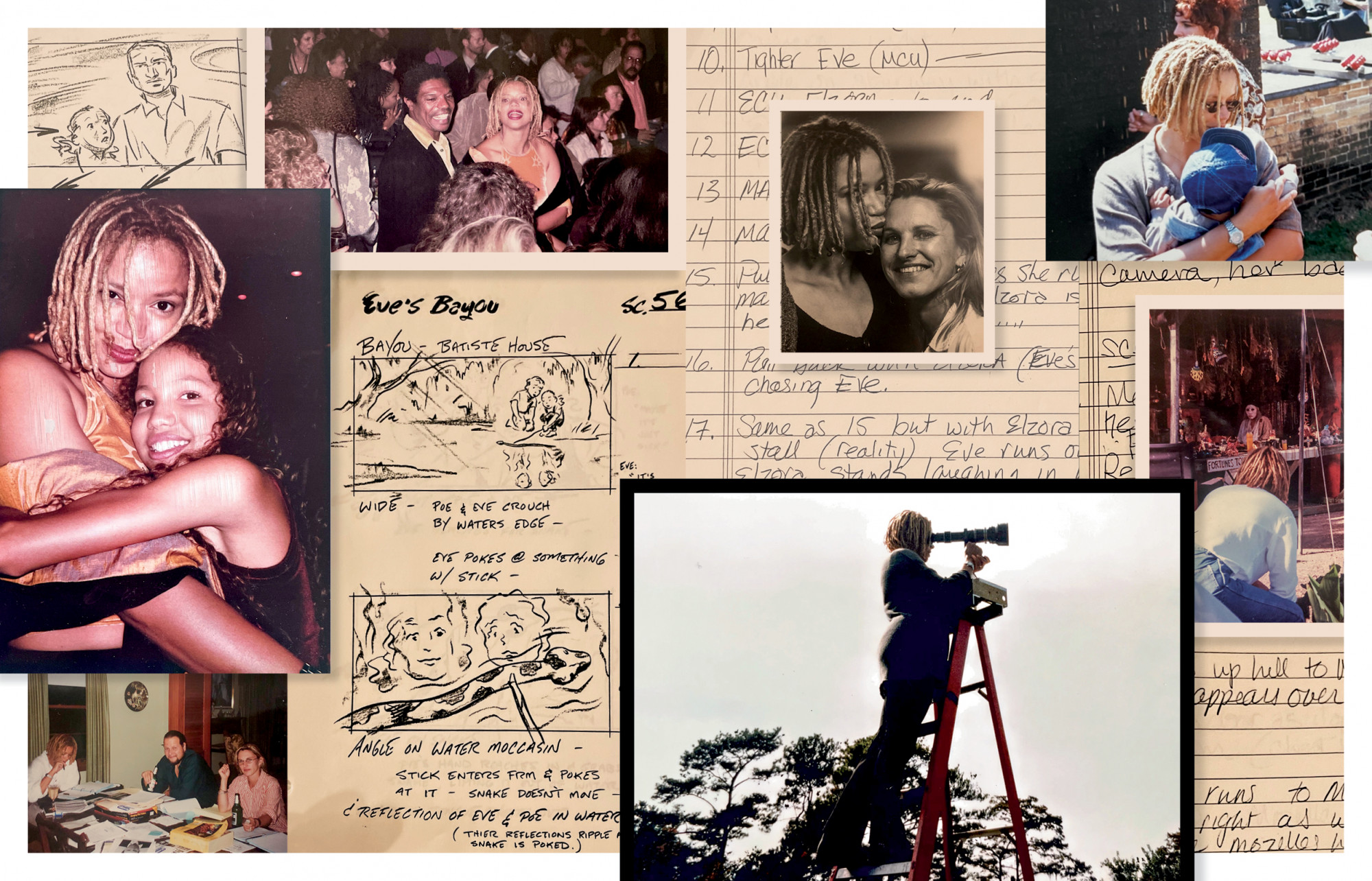

Photos from the set of Eve’s Bayou by Amy Vincent.Courtesy Kasi Lemmons. Eve's Bayou premiere photo; photo of Kasi Lemmons with Amy Vincent; and ephemera courtesy Kasi Lemmons

Is This Sacred Ground?

A Q&A with Kasi Lemmons

By Tayler Montague

It began with the voice of a woman I couldn’t see.

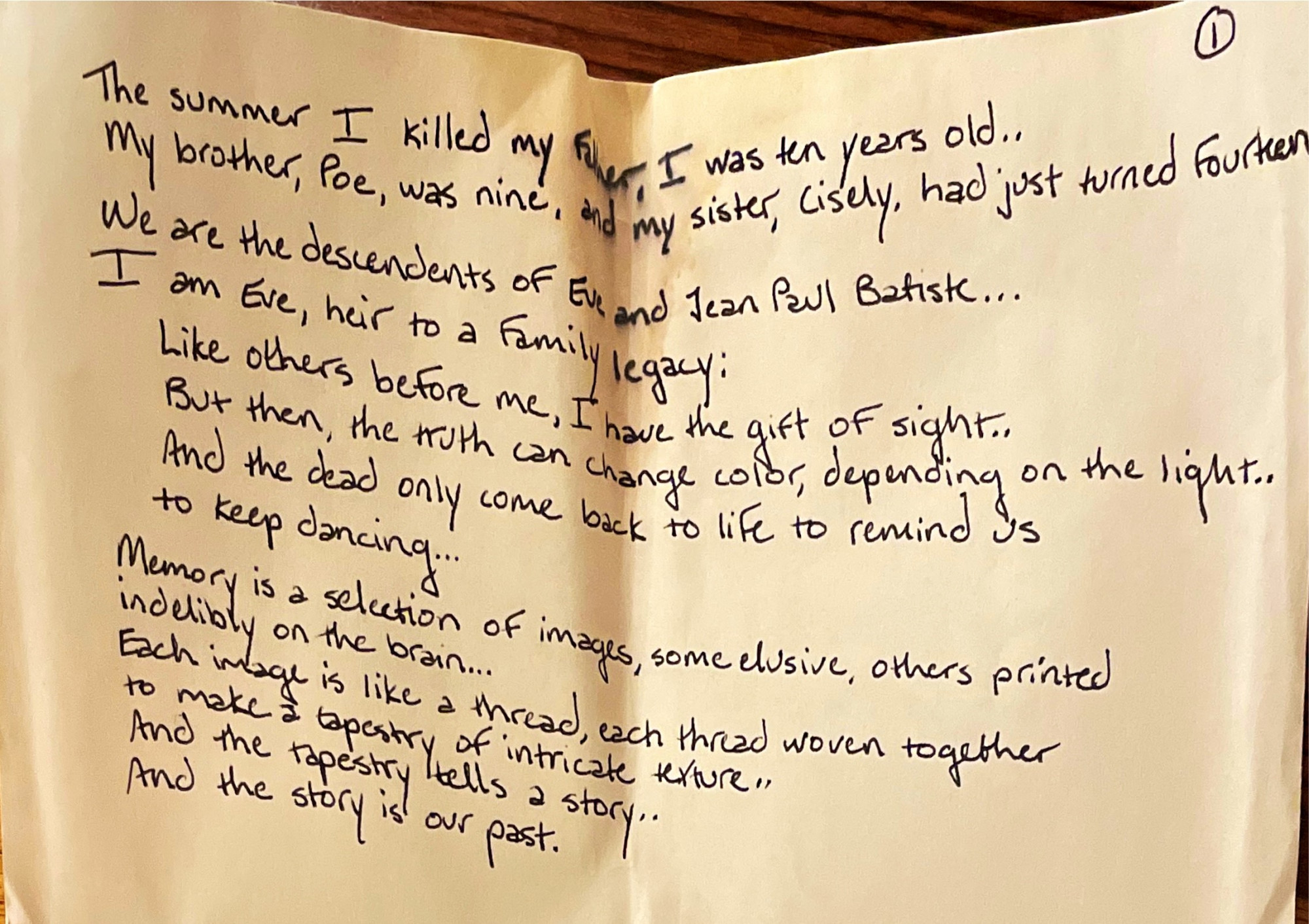

“The summer I killed my father, I was ten years old. My brother Poe was nine and my sister Cisely had just turned fourteen.”

The first time I heard that phrase uttered, I was closer in age to the ten-year-old protagonist Eve than to Cisely, and watching Eve’s Bayou in one of its many afterlives since its initial release, either on VHS from my parents’ collection or on BET, whose programming exposed a generation to films that are now solidified as classics.

A Black Southern gothic drama that takes place in the early 1960s, Eve’s Bayou tells the story of the Batiste family. Affluent, they live on the bayous of Louisiana in a beautiful, grand house. Their father, Louis, is the town doctor with a wandering eye. Their mother, Roz, seeks to keep the family together despite the toll his “house calls” are taking on them. The older daughter, Cisely, believes Roz is driving Louis away, while the ten-year-old Eve becomes a witness to one of her father’s trysts, shattering the veneer of respectability. Eve seeks guidance from both her aunt and a local conjure woman to restore the peace, but what’s wrought in the Batiste home is something else altogether.

In film scholar Kara Keeling’s essay for Criterion, “Eve’s Bayou: The Gift of Sight,” she reflects on seeing the film for the first time: “Sitting in the dark theater in 1997, I found Eve’s Bayou remarkable precisely because of the way it plunges us into the interior life of a young Black girl, asserting, with neither justification nor apology, that such a perspective belongs at the center of the frame, that it should demand our attention.”

Despite my inability to articulate this as a kid, I believe myself to have been just as enamored with the interiority of Eve, especially as her peer. In the way a child does, I found myself taking the film quite literally. I believed her and Cisely both. I was uncertain of where the fiction and reality of their stories began and ended. And I didn’t pay much mind to the heartache of the adults—I didn’t understand them the way I did Eve. Her story played in my mind: a mélange of images about a girl killing her own daddy, mirroring Eve’s cryptic memories in the film.

Then, I became a woman. And then, a filmmaker, also concerned with the interiority of Black girls and Black women. I had the opportunity to stand behind the camera myself, to try to make tangible the complexities of adolescence, to use fiction to explore greater thematic ideas of what it means to be alive. While I had always known the impact of her work, I had newfound insight on the films of Kasi Lemmons. With Eve’s Bayou, Lemmons kicked in the door in a major way. She successfully made the leap from actress to filmmaker, with a vision entirely her own. The film was released in the fall of 1997 and grossed $14 million domestically on a budget of $4 million, making it the most commercially successful independent film of that year. It launched a steady feature film directorial career for Lemmons, whose most recent film, Whitney Houston: I Wanna Dance with Somebody, was released in 2022. (I was surprised to learn during our chat that for the first time in her nearly thirty-year career, she was able to do reshoots, also called pickups, on a film.)

For this Oxford American film issue, I thought it befitting to speak to Lemmons not only about Eve’s Bayou, but also her other film shot in the South, Harriet (as well as the unrealized Battle of Cloverfield). A biopic about Harriet Tubman is potentially daunting, but in Kasi’s hands it becomes a vehicle to better understand the breadth of Tubman’s work emancipating the enslaved. I am struck by the parallels of the films, the way they both foreground inner visions as a catalyst for action. To be guided by one’s feelings is often deemed frivolous, especially for women, but in the context of Lemmons’s work there is no need for greater justification. The spiritual intuitiveness within is sufficient to guide us through life’s challenges, and there’s a rationale in hearing and validating our own selves. I also began to consider the importance of Cloverfield: Could it have completed something of a Black Southern spiritual trilogy? I find myself often interested in the ways works yet to be realized are portals into better understanding the artistic visions of a director at a particular time in their career.

I deeply admire Lemmons’s ability to amass such a wide-ranging body of work encompassing musicals, comedies, dramatic period pieces, and librettos. Our conversation focused on her filmmaking in the American South, as you cannot mention films of that region and not include Lemmons’s work.

—Tayler Montague

Courtesy Kasi Lemmons

Eve’s Bayou still courtesy the Criterion Collection

Tayler Montague: I read that you spent time in the South in your youth. What influence did spending your summers in the South have on your imagination?

Kasi Lemmons: At the time, I was very young, so we were living in St. Louis. My sisters were much older than I was. And my parents’ marriage was dissolving, so they would send me down periodically for longer spells to live with my grandmother. Her house was kind of magical. She lived in Tuskegee, and she had this house that I thought was very beautiful and unusual. The kitchen was downstairs on the garden level, and she grew her own vegetables. She had a garden and a forest in the back of her house. First the garden, and then the forest. It was a really beautiful place to be. She had a lot of antiques. She was a musician, so she had a piano and instruments. I thought that was cool. It was at a time in my life when I was very tomboyish and playing with insects. I was also at a time in my life when I got sick quite a bit. I had pneumonia several times.

One of those times that may have been pneumonia, I was hallucinating. Very vivid, very frightening. It was tactile and visual and audible. I think I was pretty marked by that, hearing voices talking to me and stuff like that. I didn’t know if it was telling me I was gonna die soon or if I was special. The voice was ambiguous. But because my mother always told me, You’re born under a lucky star, I chose to think that I was somehow touched and that this experience was part of it. It came from my childhood being sickly at my grandmother’s house and kicking mud and playing with insects and wandering through the woods. I think that that informed a lot of Eve’s Bayou. Certainly.

I was wondering if we could go a bit into the world-building of the film. I was curious about any prep or research you did in regards to the setting of the town the film takes place in. It reminded me a lot of Zora Neale Hurston and the way she talks about Eatonville. Was any of that an inspiration for you?

Zora was certainly very important to me. And so was Toni Morrison. I had written a short story that was the legend of Eve’s Bayou about Eve and Jean Paul Batiste. And then I did a lot of research. I went to Louisiana. I spoke to a Creole lost language expert. I delved a little bit into voodoo and spirituality but on the kind of magic-kismet level. It wasn’t until we were in pre-production that I found a book, I think it’s called The Lost People of the Cane River Valley. [Note: The book is The Forgotten People: Cane River’s Creoles of Color.] In this book, I found a story that almost identically mirrored my story of Jean Paul Batiste.

It was in that book, which I bought and gave to the entire crew as their welcome gift, that there were some similarities. I think somehow on a spiritual level, I plugged into certain things about the place. Obviously it was a fable. It wasn’t meant to be absolutely realistic. There were things that I was plugging into that were kind of folklore and even the history of a certain place and a certain people that informed Eve’s Bayou.

I’m also interested in talking about the more aesthetic aspects of the film. In rewatching, I was really struck by the color grade. It called to mind a lot of early color photography: Gordon Parks or William Eggleston for example. I was hoping you could talk to me about how you developed the look of the film. I know Eggleston took photos on the Eve’s Bayou set, so I was wondering if you could tell me about your relationship to his work as well?

I think he’s one of the great American photographers. I love his work, and I love some of the photographs that he took while we were down there. I was inspired, very inspired, by all kinds of photography. Not just color photography, but also some black-and-white images that were very haunting from a book called Ghosts along the Mississippi about aging mansions and bayous that had a haunted feel and just Spanish moss and the environments [of the Deep South]. I mean, color was very important to us on a lot of levels. We were using black and white as well, a very dynamic black and white. Super contrasty, black and white for the visions. The DP, Amy Vincent, she’s a genius and just a wonderful director of photography. She and I worked closely with the visual inspirations, looking at movies together, going to bookstores in New Orleans, picking up books about the area, and looking at those photographs.

I know in Harriet the ending credits have photographs taken in the tintype style of the time. I was wondering about photography being very present in a lot of your filmmaking work. What is your own connection with the medium? Do you take photos?

I do, and I have an alter ego that is a photographer. If I weren’t doing this, I would be traveling around taking photographs. Yet, I’m not very technical. I know a frame when I see it. I know beautiful light when I see it. There was a time when I went to school and I wanted to be a cinematographer. When I went to film school, I thought I was interested in documentary filmmaking and I thought it would fill the time between being an actor, which is of course my first love. But my technical stuff ended at film school. Right now, my students know so much more about cameras than I do, but I could frame and capture. That’s really what I’m good at. I shoot about a shot per movie, but I leave it to my brilliant friends to deal with the photography and usually work with the DP on how I want it to feel and in designing the shots.

For the photographs in Harriet, I believe it was my brilliant prop master, Steve George—he’s no longer with us—he introduced me to his friend, who was great at [tintype] photography. He had the old plates and the old cameras that he actually shot with.

It’s gorgeous, really striking. Hearing you speak, it does seem like despite maybe not having all the technical answers, you are directing these beautiful images and these great performances. I’m wondering if directing is an instinctual or spiritual thing for you?

One of the things about teaching film, which I love, is that it forces you to quantify your actual information. Before I started teaching, I never thought about [directing] as completely instinctual. Because I have an anxiety disorder, I am very prepared. I plot out the whole movie and prepare the movie and know exactly what I’m shooting. There’s a methodology behind it. But in terms of directing actors and being present and available in the moment and seeing what’s in front of me and having an instinctual physical reaction to what is the right thing and what’s gonna be usable, I would say it was very instinctual. One thing that I’ve noticed about myself is that I can be anxious, a little socially awkward, a little shy and self-conscious—except when I’m directing. Directing, in a weird way, relaxes me. It’s so stressful and there’s so much to think about. You have to be so present that I get über-focused, like I’m plugging into something. In that way, there’s a spirituality to it as there is with acting. I would be nervous until I started acting, and then once I started, [I would have to] be so available to the moment that I found it relaxing. That’s when something else kind of works with you and through you.

I’m very curious about these motifs that you have as a director. I saw a lot of parallels in the filmmaking styles of Eve’s Bayou and Harriet, for example. Not only the use of photographs, but mirrored images and the black-and-white or sepia-toned flashbacks. How did you cultivate these motifs, and how do you bring them forward to represent certain things like memory?

Yeah. Memory. Eve’s Bayou was interesting because we had to choose a visual language for each thing. You have flashbacks and ghosts and memories, right? And visions! How do you take those elements and give them a distinct photographic language or film rate? We talked a lot about that, how to distinguish them. There is this kind of truth to the way that I experience what I call visions or flashes of insight or whatever it is. In some ways I’m doing [these] the way [they] look to me. Usually mine are very mundane. If I’m working closely with a coworker, I might have a flash of something that might happen to them, you know? Often it’s a very graphic black-and-white image that is heavy with symbolism. It’s not… I’m not very good at telling the future or anything like that (laughter). I don’t have those kinds of visions.

Kasi Lemmons (L) and Cynthia Erivo on set courtesy Focus Features

Harriet still © TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy

Photo from the set of Harriet © Glen Wilson / @dubarts

Photo from the set of Harriet © Glen Wilson / @dubarts

Photo from the set of Harriet © Glen Wilson / @dubarts

What is the process of making something in your mind—a short story or even your visions—legible on screen?

I think that you’re always searching for it. You’re searching for the truth of human behavior. You’re searching for how dreams look; you’re searching for how things feel. Well, you’re searching for life, and the way the mind works, and it’s imperfect. You’re always reaching for it. Especially when it comes to imagination and dreams and memory. I was trying [in Eve’s Bayou] to really explore how it feels to remember things and the way we remember things and what traumatic memory does and how the mind plays tricks on you. I don’t know that I’ve ever nailed it and been like, Okay, that is what it feels like.

The same with authentic human behavior. We’re always reaching for it through our actors. It’s such a wonderful lifelong journey ’cause you can never quite, you know, get great at it. Or if you get great at it for a moment, then it’s elusive.

What was your approach to showing the fainting spells in Harriet? Because it’s not only specific to a person but to someone who is also a great historical figure, right?

Well, who knows what it looked like to Harriet, but we did know some things. She says she experienced [the fainting spells] sometimes as flying. We tried to use that in a shot, kind of moving over the field of enslaved people working. We knew certain things about the way she said it felt. There was an aspect of it that historians think was a seizure. We tried to give it sonically some feeling of that. I read a lot about the way that people experience seizures and what you might see. [Harriet] could make sense of these dreams. Some of them are very far out. She describes them extremely symbolically. We couldn’t shoot in Harriet everything that we wanted to shoot because we never got a chance to do pickups. And I gotta say on the Whitney movie, that was the first time I’ve ever been allowed to do pickups, and re-shoots were out of the question on anything that I’ve ever done. So it’s like, what you get on set is what you get. With Eve’s Bayou, the visions were very much designed that we were gonna come back from location and then shoot the visions. And in Harriet, we had to shoot them while we were moving as fast as we could through the movie. So, it was tricky to capture, honestly. But we did have some information about how she experienced them, and we did try to shoot some of that and then put it together in the edit.

Since you’d never had an opportunity to do pickups before the most recent film you made, I was curious about the process of discovering a new film in the edit—maybe it differs from your original vision, but it still encapsulates everything you wanted to say.

Yeah, it’s so interesting, especially in Harriet. We went through a process because the visions were in color and sometimes they were in different colors. Then gradually they became more and more black and white, monochromatic. Ultimately I conformed them to the way that it looks to me. But it was a process in the editing of putting it together and trying different images together and finding little moments that were almost unusual or unusable material—[for instance] after I say “cut” and the camera moves—and going, Okay, that piece is an interesting piece for a vision.

Absolutely. Is there an aspect of filmmaking that you like most?

Well, I love editing. I really, really love editing. But I would say my happiest place is on set with the actors. I think my work with the actors and the kind of alchemy that you find on set when it’s immediately happening in front of you and you have to make minute adjustments—there’s something very intense and very Zen and very magical [about it] that I love.

How did you cultivate the skill of directing actors? I know you were an actress before, and I was wondering if that experience on sets informed the way you direct?

It was very instinctual, but it was in my first film, after I had shot, that I watched the electronic press kit, and I saw actors talking about the way that I direct, and they said, Oh, because she was an actor. And then I realized, yes, of course it’s because I was an actor that I’m able to know how to talk to actors, and in some ways, I borrowed things that worked for me. I knew that I wanted it to be a private conversation. I knew I didn’t want to raise my voice. I knew the intensity and presence of Jonathan Demme was very important to me. The quiet power of Spike Lee was very important to me. The hand signals that John Woo used to use because his English was still not good when he was doing his first American film, Hard Target, came to be important to my directing later on.

I’d worked with really great directors and I didn’t think about it. I was too busy trying to hit my marks and, you know, come up with a performance. Like I said, I didn’t really think about it until I started teaching because you have to somehow teach your methodology or the things that have been helpful to you. You want to communicate that to the filmmakers that you’re helping to educate. I came up with a way of talking about things that were instinctual to me.

Kasi Lemmons on the set of Harriet. Photo courtesy Focus Features

We’re discussing a lot of your filmmaking work in the South; Harriet was mostly shot in Virginia. What is the location scouting process like? What are you looking for? What are the conversations that are being had?

It’s interesting that you’ve chosen these projects that happen in the South because the way of talking about them is gonna be a little different. It’s always similar in that you’re always searching for a feeling of a location. But the South is a complex place, and it contains so much of our blood. With Eve’s Bayou, I knew I didn’t want them to live in a former plantation. I didn’t think the Batistes lived on a plantation. And so, of course, when you’re looking for houses like that, you’re looking at plantation houses and that doesn’t feel right. [The Batistes] were the epitome of freedom to me. The color of their walls was a color for me that represents freedom. They were free. They had a history of enslavement way back, but there was a freedom to them that was important to me. And so I turned down a lot of plantations, saw a lot of plantations all around the South—North Carolina, South Carolina, all over. Then we came to Louisiana, because that’s where [the film] takes place. It has a certain look that, I mean—it’s almost like cheating to shoot in Louisiana. It’s so beautiful. That look was very important to me, but also the way the place felt was very important to me.

Harriet became a really interesting experience because now I’m looking for a plantation, but it had to have what I wanted it to feel like. And I scouted plantations that gave me some horror. Spiritually you walk on and you’re like, Oh man, bad shit happened here. And it’s still haunted, and not in a way that I appreciate. I don’t mind the ghosts of the past, but it has to speak to me. I remember the first time I walked onto the plantation where we shot Harriet, the insects and the birds and nature sounds. It was like going to church. I felt that it was hallowed ground. There had been blood spilled, the people had suffered and worked, but also lived and loved. These were full human beings. Their toil and their love and their desire for freedom and their blood were in the earth. Not in a way that made me want to run screaming, in a way that drew me to them. That’s what I was looking for. We went on a very spiritual journey to find the main location, the Brodess Farm, in Harriet.

And what is it like commanding a set in an environment like that? What are the conversations you’re having with the cast and crew about where they are and the kind of work that you all are doing?

Everybody that came to play was doing it for Harriet.

If you ask any of my crew they’d say, Well, I was doing it for Harriet. They were all there to tell that story. But specifically, we talked about the importance of saying enslaved people and not slave, not calling the extras slaves. I called them “The Righteous.” I’d say, The Righteous are in the fields, just a way of talking that was a little bit different, a way of showing my African American Southern appreciation for what that situation was and who these people were that I know impacted the day players and the extras and people that worked on the film. I tried to watch how I spoke and model that for the crew and watch how the ADs [assistant directors] were treating people and make sure that they understood what’s important here and what’s important to me. But it was not difficult to communicate that to this crew because they came to the project to tell the Harriet Tubman story. Now, we scouted some places [and got] a hostile reception, you know? And okay, well, Thank you. Good day. We’re not gonna shoot there. But by the time we had the location that we shot in, the gentleman that owned that place—the place was very important to him and his family—he also wanted to tell the story. We had a lot of goodwill amongst us and a bonding vision that had to do with Harriet Tubman herself.

Thank you for taking the care. It comes through in the film. In your earlier interviews, you were talking about potentially directing what was to be your second feature, entitled The Battle of Cloverfield. I wanted to know what the story was and what your vision was. I couldn’t find much. It seems like it would have been in the Black Southern gothic tradition that you have been making films in.

Absolutely. It was a ghost story. It had to do with the history that’s in the earth once again. Is this sacred ground? What needs to be preserved about it? It was about land rights: What can be dug up and what needs to be preserved? If you have a battlefield, is that sacred ground? And is it sacred to who? This was a story about a small town in Virginia, a fictitious town, where an important battle had been fought and a [later] fight over that land: Should it be developed or should it be preserved? It was Civil War–related.

At one point I read that Laurence Fishburne was attached to it. Can you speak about that?

It really was about the mayor of Cloverfield, a Black mayor in a town in the South. And, I wanted to do it with Fishburne. We were very, very passionate about it. We tried hard to get it made. It was ahead of its time, like a lot of my work. As Black people trying to tell dramas about our history, they’re painful and also spiritual. It was a period piece. It wasn’t a long time ago, but it was a drama.

Black dramas were very hard to do. We were told over and over again, Black films don’t sell foreign. Black dramas, there’s not an audience for them. Or, It’s a very, very, very small audience, and you have a big vision. If you were doing a very small film, maybe you could get it made. But if it had scope and an epic-ness, it is just very difficult to get those films made. We loved that project, and I tried many different iterations of it. Ultimately, we couldn’t get it made. Fish and I really were passionate about this story, and I was passionate about working with him.

Is there a dream project for you?

There’s a few! My favorite script that I’ve adapted [is] Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King. I’ve been trying to make The Shadow King. I love this book. It’s gorgeous. It has to do with Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Resistance and women warriors. That’s one of my dream projects. Then there’s a script that I wrote twenty years ago that I love and am actively trying to get made. I’m very hopeful that I’ll be able to make them in the future.

I wanted to talk a bit about the themes of family in these films. Sometimes when we talk about family, there’s this need to protect or maybe to be a little less transparent. You’ve talked about aspects of your own family background slipping into Eve’s Bayou. You are kind of fearless in that sense, to just go for it.

I really don’t know exactly where I found the courage to do that. I think part of it was, I was in therapy at the time. My therapist actually told me to write about it. I knew I couldn’t write my own story. I was very much a fictionist; I could make up stuff for days. I started to write these short stories that had to do a little bit with my family, but also had to do with folklore, and those stories became Eve’s Bayou. Honestly, I put in the dialogue things that I heard when I was a kid that were in some ways a love language that was harsh like: “Play games with me, I swear I’ll slap you blind.” Also, bits of characters: a lot of my aunt, a lot of my mother, some of my sister, and, yes, some of my father. But because it was so fictionalized, I didn’t really think about it. I remember when my mother saw the film and she said, God, that was just like that. I realized I had actually captured more of them than I might have even intended to.

Harriet was different because I thought, How do you tell a story that is very humanizing about an enslaved woman? Harriet’s story was all family. You know, Harriet went back to get her family and happened to bring other people along, before the mission just became, How many people can I free?

I mean, it’s unbearably cruel to think about. There were many stories, of course—you can’t even contain it all in a film. Harriet’s life is so big and dynamic. It’s a sliver of the Harriet Tubman story, but there was just unbearable, painful family separation. Her mother had been very traumatized by that. The other thing that was absolutely fascinating about Harriet was that her father was a free man. I thought that’s an aspect of slavery that we might not understand. It’s nuanced. Enslaved people and free people of color were living in very close proximity to each other. She could go visit where her father was. That also had its own cruelty, but was very interesting.

I’m also curious about the themes of motherhood in Eve’s Bayou. Shortly before you shot the film, you became a mom. And I was curious if that experience brought more nuance to the story or influenced the way you shot it.

It probably had to have, as I was madly in love with my son. I was postpartum for my first two movies. My daughter was incredibly young when I started shooting my second movie. And my son was very young when I started shooting Eve’s Bayou. They were on set and present with me. I was feeling that: being torn between being with my babies and creating the vision. It had to have been very powerfully informed by that. But I can’t say I overthought it. I do think that my maternal instincts have always been present when I’m directing. With those two young actresses, Jurnee [Smollett] and Meagan [Good], I look at pictures that they took on set, and my arms are always around them. I think I felt very maternally toward them, very protective of them.

Did that influence the way you directed them toward certain performances? Because there are aspects of the film that maybe a child doesn’t completely understand.

Yeah. I let them understand it at their own rate. I always tell my students too: One of the first most powerful questions that you can ask an actor is, have you read the script? Has your mother read the script? I had [Jurnee and Meagan’s] mothers there with them who would talk them through things as well. And then of course, when you’re shooting, the actor that you’re working with doesn’t always have to go through what you’re putting the character through. Eve, she’s acting like she sees what is happening, but she doesn’t have to, I don’t have to do that to her. I can spare her from that because she’s such a good actress. I can talk her through it: “You’re seeing something incredibly frightening. First of all, do you know what the scene is about?” She’s like, yeah, “I went over it with my mother.” We talked about it. With any actor, but especially with kids, it can be helpful to talk to them off-screen even as they’re acting. Like I said, it was very instinctual.

You’ve talked about how teaching unlocks your capacity to direct. Does that crystallize anything or bring you closer to any truths when you’re embarking on a project?

I wonder if it does. I don’t know the answer to that question. I think that I still get on set and do it instinctually, something kicks in. I do try to explain to my students the language that I use. I use images a lot when I’m directing actors. Because I don’t think they’re often taught that way. Images are very important to me, and images can be very useful to actors. And I know that. So that’s kind of just teaching what I use in terms of it informing me. I would say it keeps me inspired. I’m very inspired by my students.

Directing, so much of it, is preparation. And then you get on set and it’s like jumping off a cliff and then hoping you grow wings.

There’s a moment in Eve’s Bayou where Lynn Whitfield’s character, Roz, is watching her husband dance with another woman. I remember saying to her, it’s like sand through your fingers. You know you can’t hold it. You’re trying, but you can’t. Or it’s lead and a weight in your stomach, things like that. A lot of it has to do with sensation. I don’t have a bunch of them that I can recite to you. It’s very much in the moment.

Is there anything that people don’t ask you or haven’t asked you that you’ve been wanting to talk about or wanting to speak to?

You touched on something that’s very important to me. Reflections are very important. I appreciate their presence in my movies. Photographs… I think of my filmmaking and my taste as being quite diverse. I think that it lends itself, when you talk about Eve’s Bayou and Harriet together, because those films are similar. The spirituality even of where I was shooting and my approach to location scouting was very, very important to me. But also, Talk To Me is one of my favorite films. It shows a lot of different kinds of sides of myself. Not just the spiritual woman from the South. I am moving more towards myself now.