Anita Baker Introduced Us and Patrice Rushen Did the Rest

By Ed Pavlić

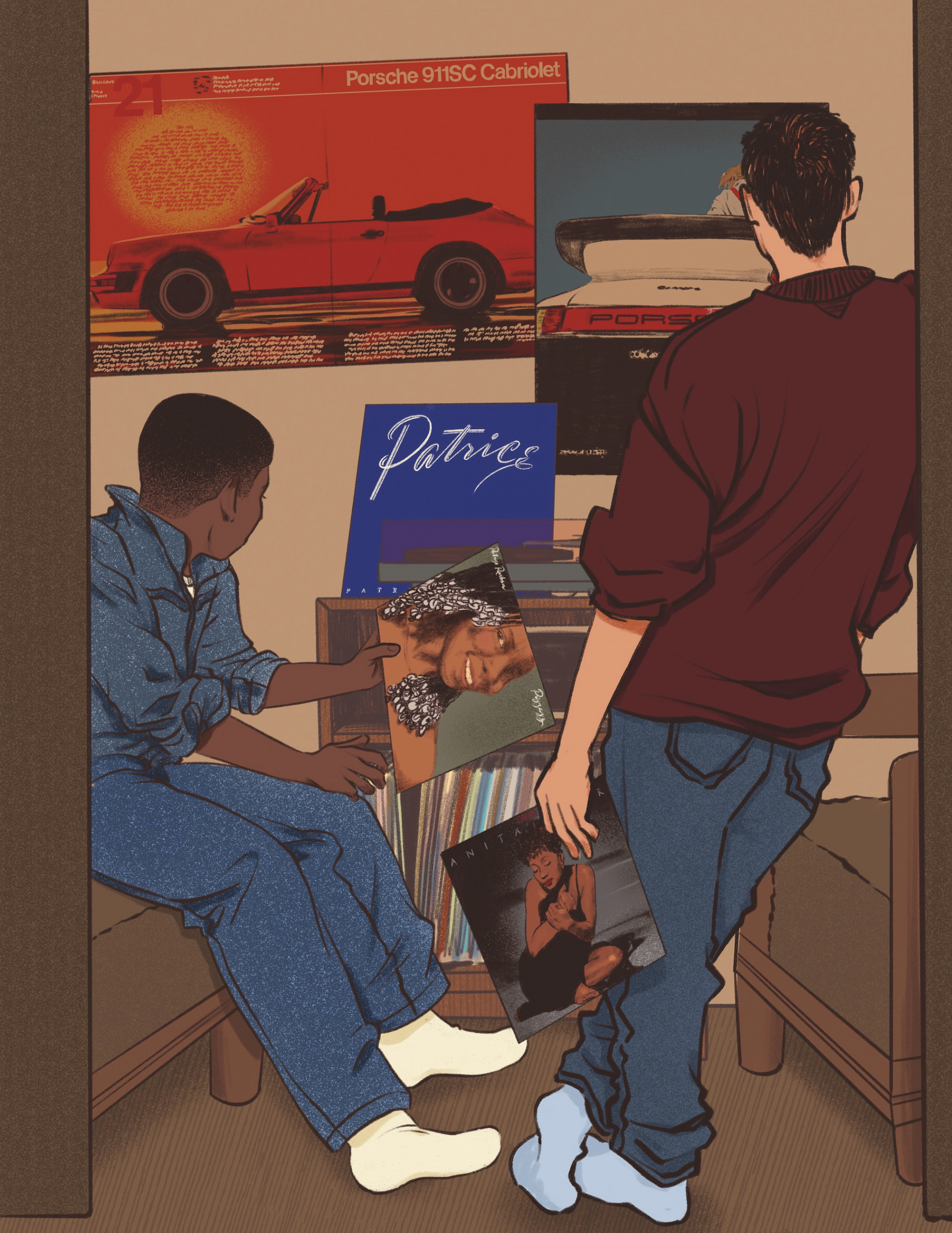

Illustration by Rachelle Baker

12:45 A.M. SEPTEMBER 2, 1986.

It’s dark now and the balcony makes it seem like we’re sitting up in the middle of the night sky high above the glow from Dayton Street in Madison. Ric talks and I think, “Well he’s not small because he don’t eat that’s for damn sure.” An empty carton of mozzarella sticks sits open on a large pizza box, also empty, which covers most of the patio-type table we made from two milk crates emptied of my records. Remembering Liz’s lesson from last summer about drinking vodka with grapefruit juice has helped me defend myself against repeating unavoidable evenings like that one that got out of hand at La Maison du Caviar in Paris. I’ve mixed the grapefruit between as much ice and as little liquor as possible, so this tastes like cold juice with some distant heat lost in it. I don’t see the point of drinking at all but, up here, tonight, and diluted as much as possible, okay I don’t mind it. And Ric’s not all theatrical and pushy about it like Claude Haddad and his Lebanese-exile crew yelling at me, “Yalla, Eddie, Yalla!”

“They don’t scratch, ever, and you can set them to repeat like an auto-reverse tape deck. Just think: pure music, no skipping and popping.” Ric’s convinced cds are the future and that we’ll need a cd player in here asap. Back down the hall in the living room Anita Baker’s singing about See about me… Come on see about me. Her scatting fades out and Ric rises up out of his chair, saying, “See this, I’m talking about no getting up to flip the record.” I can see it. But then what happens to the records? We gotta buy it all again? I’d heard “Sweet Love” and “You Bring Me Joy” on the radio, but I hadn’t heard Rapture before leaving for Boston for work last spring and then on to France for the summer. I take a moment to feel the dark breeze curl over the low balcony wall and notice how three radio towers slow-strobe in the distance. Ric steps back onto the balcony followed by a woman singing turning back the hands of time… “Mystery,” first song, side two on Rapture. I’m not sure if it’s the trip back from Greece to Paris to Chicago to Madison and then today and the run-in with the sheriff and the mess with Terrance, or if it’s something else that feels like it’s coming out from behind the air in every direction at once, but I haven’t ever heard anything like this album on this balcony before. Did she just sing Only images survive? Ric sees this in my face: “I’m telling you, E, you stay over there too long and get culturally deprived. Might as well be sub-urban.” He says that last part like it’s a synonym for subhuman then, “Hell, Madison’s bad enough! But at least I can get home in a hour.” I think, home? To Chicago? In an hour?

I want to tell him about the no-gravity-suspended feeling among the murmurs of Parisians in the streets of Beaubourg, the relief from the way everything in the U.S. feels like it’s trying to tear itself (or at least me) apart. But it’s not the time. I’m watching him talk and mostly listening to the album and balancing what Anita Baker’s doing with these songs against the grim imitations of togetherness I remember from those Paris discos. I haven’t even noticed the invisible things weaving Ric and me into each other right here yet; it’s too close. Instead, I’m feeling that moment when the Commodores’ “Lady” appeared out of Euro-drone in the disco and the warmth of people dawned behind my eyes like it was cut through by the vanishing groove in the cold spray from the brick saw. That warmth and those people weren’t in that disco, that was all in me. That image, though, the diamond blade, the vanishing groove, comes and goes from my body like it’s made itself a home in me. Like maybe it is only images that survive?

Twelve hours ago I was sitting on a picnic table at the Union with no place to live. I hadn’t planned on coming back to school at all, at least not now. My plan—which okay wasn’t a plan—had been to stay in Paris, where I’d lived half the summer riding along with the modeling industry run amok, my girlfriend T and her roommates and the agency owner Claude and a buzzing cloud of his generously pushy friends whose need for “company” seemed as endless as their cashflow. I had the little money I’d made earlier this summer running a brick saw for a small construction crew in the tank room of a Budweiser brewery in New Hampshire. Don’t ask. I’m not sure about how it all comes together either.

Twelve hours ago I hadn’t really even met Riccardo Williams, who, somewhere between noon today and midnight tonight became my best friend, and, who, a little less than a year from now, and according to a scale of lived time there’s no measure for, will die of a sickle cell crisis and vanish from—but leave a permanent hole blasted out of—my life as fast as he’d appeared into it. Before today I’d mainly known Ric through Terrance, who I’d run into just before leaving town last spring; Terrance talking about they might be looking for a roommate for next fall and would I be down? I’d said I’d think about it and then forgot about it. Until the moment my plane touched down at O’Hare yesterday at 5:05 P.M. and I realized I’d returned to school and I had nowhere to live.

So, then, a few minutes before noon today: I rang the buzzer to this apartment, #902, unannounced; woke up Ric, who had rolled into town himself about an hour before me and gone back to sleep; asked Ric if he was cool with another roommate; drove across town to clear it with Terrance at his shady-ass job “selling art” for a boss who’s about as legit as the bootleg Patrick Nagel prints he had Terrance hawking by phone; went back, moved in our stuff, and got to cleaning the place after Terrance and whoever else had hurricane’d in it all summer, which went along okay but for a hole smashed in the hallway wall and a football-shaped spot burned into the carpet—Ric: “I can’t believe them fools was ’basin’ in here”—in the living room; talked for the first time with Ric over Parthenon Gyros and George Howard’s A Nice Place to Be, a conversation that began to distantly sparkle over Howard’s version of Sade’s “The Sweetest Taboo” just when the sheriff showed up with an eviction notice talking about how no rent (which, each month, Ric had sent to Terrance) had been paid all summer and so we, or someone, owed $1,575 before Friday or we best get to packing up or deputies would do it for us starting end of this week at eight A.M.; agreed to Ric’s claim that if I “invested” $1,000 of my savings from the brick saw in the brewery into paying the back rent and solving the shit with the sheriff it would pay off and pay off quick; then paused the cleaning work to pack up all Terrance’s shit in Hefty bags—everything except his Raleigh Technium road bike that Ric said he’d deal with after he figured out exactly how pissed he was and how pissed he wasn’t—and deliver the load to shady bossman’s ranch-style house where Terrance—talking about “man I know, my bad on the rent man, my bad”—had already been staying; then finished finishing the cleaning, leaving the oven—Jesus, the oven—for later and Ric saying how he thought this was a day that could end with a six-pack of La Cerveza Mas Fina between new roommates but that was now going to have to be an evening with a bag of ice and a bottle of Stolichnaya and whatever I want in between—and me: “in between?” and Ric: “between the vodka and the ice!” and me keeping quiet about the fact that I drank alcohol reluctantly and only when it absolutely couldn’t be avoided, like with Claude and his gold-Cartier’d, red-Ferrari’d, silk-unbuttoned confrères and Ric looking me directly in my eyes and saying without saying this was absolutely one of those unavoidable nights I was keeping quiet about.

All that earlier today and yet still spiraling through the cooling evening air around us.

Rapture and us on this balcony casts the sun, the saw, and the vanished groove. All of it. One after another these songs start in some small, safe and secure place, places that feel cozy or blurry or both, it’s home, a home in people, home between people. But sleepy. Then, in a few minutes, and without ever leaving home, which, when she sings it, like a picture in a frame, it remains the same, these songs sear and soar and search. Wide awake: See about me, come see about me-e; it’s a desperate plea and an open taunt. Basic as Ms. Baker barefoot on the album cover. All these songs say “Come closer, I dare you.” But, closer to what? We take turns getting up, flipping the record over, and playing it again. This is how we meet. Each other, yes, but also something far, far beyond ourselves: a need, a burning, to make a formal acquaintance with flaming mysteries we’ll never understand. Come closer to that. Flames we have to keep and connect and not let burn the whole shit down. Saying far more than it’ll ever say, a song about how something or someone been so long sings now don’t you understand… I need you to come closer, I can’t hide. And when she sings “hide” the word opens up, wide, and there they are: all the people. We talk on and on. Each song searches itself, searches us both, and, without us noticing, pushes us closer. This started right here above Dayton Street on September 1, 1986. And meantime all this—the meeting up inside the meeting up—happens far, far away from here and, probably, a long, long time ago. As if from far away and long ago, the soaring and searching inside these songs release a meeting up from inside our meeting up. There’s a rhythm up in this, too, and another rhythm up inside that. I feel my weight shift in my chair as the balcony, or the building, or the whole hemisphere begins to rock back and forth.

Over Anita Baker singing about I can’t do I can’t do without you… now don’t ask me to, Ric describes his family. He’s the only child and lives in a townhouse on South Michigan Ave. with his mom and dad. There are family businesses, vaguely described, an office on South Vincennes Ave., city contracts, a trucking company, the Tree House, a hotel in Negril, Jamaica, where he says we need to go. A grandmama he calls Ms. Lou is married to a South Side alderman, Beavers, which, as Ric puts it, “covers a whole lot. And with Harold Washington in office? A whole lot.” He looks at me and asks, or really he just states:

I have no idea what he means. From comings and goings of friends and family when I was a kid, from following Chicago Public League basketball over the years and from coming to know all the Black students in the AOP during my first year at UW, I’d learned about a range of Chicago high schools: Taft, Westinghouse, CVS, Kenwood, Lindblom, Mendel, Whitney Young, Simeon, and MLK along with South Shore High School, where my mother graduated. But Ric says he went to a school on the Near North Side, at North Ave. and Clarke St., near Lincoln Park: “Latin. The Latin School of Chicago?” I say I never heard of it. He laughs and says that’s because it’s a small private school, “probably the best in the city.” Then he leans back and smiles, “See you don’t know nothing about that, I tried to tell you the way we got it covers a lot.” Are you happy now with your life? blows onto the balcony from Rapture and I remember, just a few hours ago, how Ric, sounding a lot like he just did, had handled that sheriff like a charmer handles a snake.

As he talks to me Ric spins a thin ring, a gold snake with ruby eyes that wraps almost three times around his right pinkie finger. The light on the balcony gathers around the ring and loops back and forth between the eyes of the snake and the matching shimmer from a gold Mercedes-Benz medallion that hangs from a thin chain high in the middle of his chest. Ric weaves through sentences the same as he’d driven through traffic earlier today. I follow along remembering those few times last year how space seemed to clear out in conversations among us when he spoke. He says last year he flew home (flew home? So that’s the “home in a hour” thing) about twice a month but he plans to cut that back to maybe once a month this year. Ultimately, he doesn’t see graduating from UW, more likely he’ll transfer to a Chicago school, probably Northwestern, maybe junior year. I say I go to UW because in-state tuition is like $350 a term. Ric says his high school cost waaay more than his out-of-state tuition at UW. He mostly came up here for a little independence that was also close to home and, then holding up his cloudy glass of vodka and grapefruit juice on ice, “because the drinking age up here is eighteen. My Ps play me pretty close. And I love ’em but damn.”

We talk and talk more about France and last year at school and T and Valerie and Feeda and the Ferraris and about, before that, how I finished high school trapped in a little all-white town in Wisconsin, “that shit was like a blizzard that never stopped.” Ric says, “My brother I know they musta loved them some you.” Ric’s got at least one serious-sounding girlfriend in Chicago, Lisa, a connection as he describes it that feels familiar to me from mine in France. Then he says “but if I go home and don’t want to be home I can always stay with Deborah, one of my pops’s women.” I let that one go by. None of the details we’re saying really matter that much. Whatever’s really happening is far away and also riding inside these words like whatever imminence has been hiding behind the air for about the last ten hours since the sheriff interrupted our conversation over gyros and George Howard. Anita Baker’s Rapture blooms searing searches out of simple, sleepy scenes and sentences and, by ten P.M., after a box of mozzarella sticks, a large pizza, and a few splashes of heat into glasses of grapefruit juice, we both feel this thing—bottomless and nameless—start to pour over us or out of us or into us as if the air itself is doing that thing where you turn your t-shirt inside out without taking it off. A song says been so long missing you baby. But what’s there for two twenty-year-olds who, anyway, just met to say about that? A few minutes later, and after who knows how many times we’d flipped the record over, Anita Baker rips apart some silly sentence about no one in the world loving her and she’s breaking inside and the words burn around us in the air, flare after flare softens the sharp edges of the late-summer night as it cools into tomorrow.

I feel my weight shift in my chair as the balcony, or the building, or the whole hemisphere begins to rock back and forth.

Ric stands up, stretches, and says, “Come on let’s finish fixing this place and get it into shape suitable for guests who ain’t baseheads.”

“Who,” I ask, “do you have in mind?”

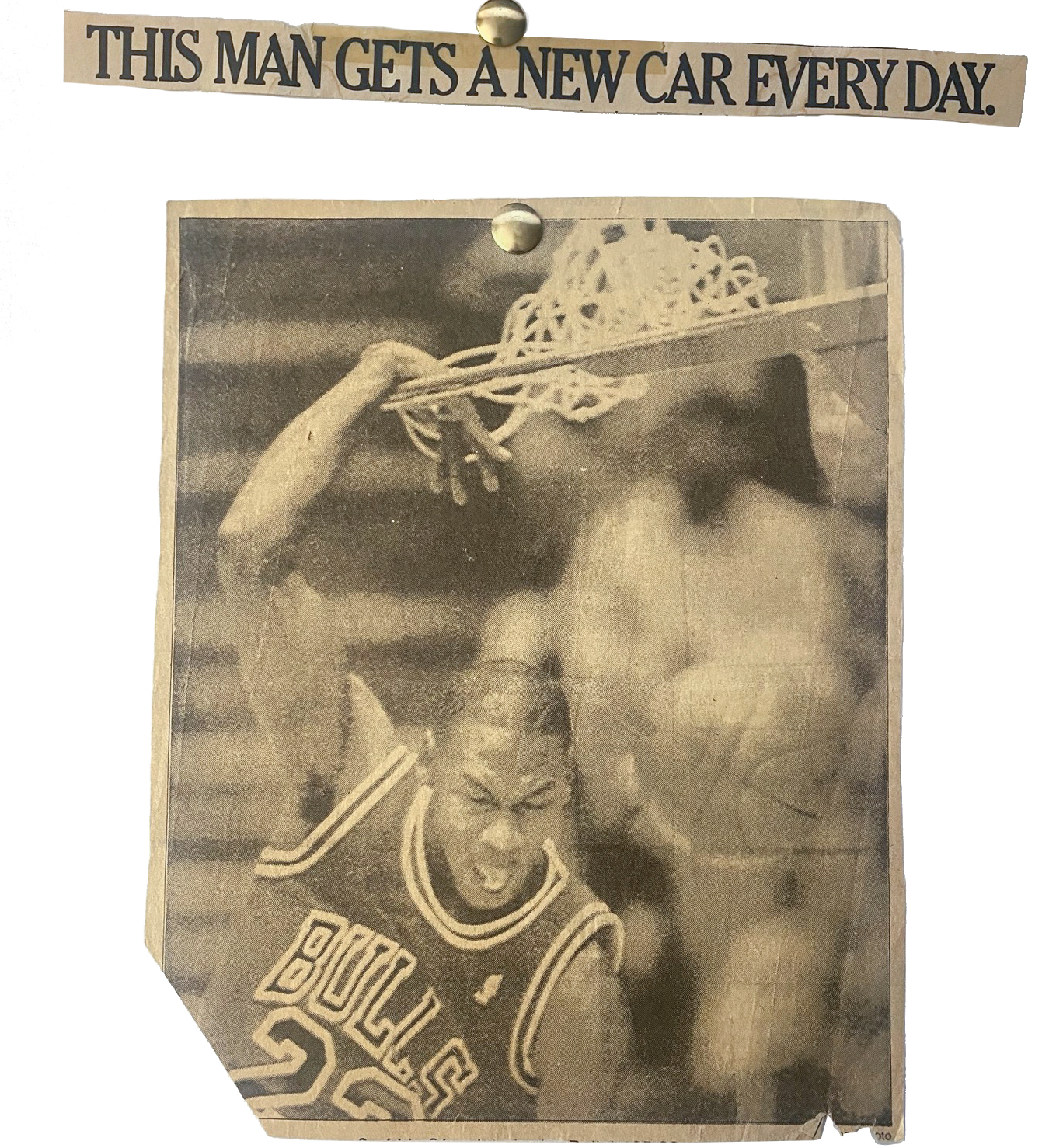

“We’ll see about that this week.” He goes inside and walks over to the wall between the door to the hallway and the row of closets Terrance’s bike leans against. On that wall hangs a poster of a white Porsche 911, the one with the whale tail spoiler. It’s unframed but fixed to a plastic foam mat. “Hold this,” Ric says to me, taking down the poster. He holds up his chin with his hand, thinker style, and then, “I know what goes here.” Removing a gold thumbtack from the wall, he turns around and digs a folder out of a bookbag sitting on the foot of his bed. He opens the folder and takes out a six-inch slip of paper. Maybe a half-inch wide, it looks like a headline or a piece of ad copy he’s cut out of a magazine. He turns back around and pierces the gold tack through the slip of paper and then sticks it back in at the center of the wall where it used to hang the poster of the Porsche. Ric steps back making a fake camera frame by touching index fingers and thumbs extended. He nods approvingly, “That’ll work.” I turn to my right so I can see what he did on the wall around the poster I’m holding. A headline:

THIS MAN GETS A NEW CAR EVERY DAY

Now I hand him the poster, “Okay my turn.” Leaving the bedroom I enter my room via the hallway door and take out a red folder where I keep clippings like that. Mine are mostly photos of the best moves I cut from Sports Illustrated. Moves like the one where Dr. J dunks on Bird and the whole Celtics squad. But I know exactly the one I’m looking for. Coming back in I tell Ric to turn around and, just below the headline, I tack the photo to the wall with one of the gold thumbtacks lying on top of his dresser: This photo’s not large, about 5 x 7, so it fits underneath the headline, which now reads like the photo’s caption.

“Oh man, MJ, yes! Look at the wrist. Fingers extended—He’s gonna take the whole city. He’ll take the league too if they can get him a team. Brad Sellers ain’t it. You should have heard Bonnie DeShong all summer throwing it at MJ on WGCI inviting him over to her house so she could play piano for him in the dark.”

“For real? I thought she did traffic.”

“Exactly! She keeps taunting him with traffic updates and the hours of night when the travel times are best.”

Next we take the Porsche poster into the hallway across from the bathroom where the wall’s busted in. Ric pushes in another gold thumbtack and hangs the poster over the hole in the wall.

“That’ll just about do that. What do you think?”

“Imma get me one of these.” He gestures to the car on the poster.

I laugh. “Yeah right, me too.”

But Ric doesn’t laugh. He points his thin finger at me, cocks his head to the side and says, “Man, you know what?” I’m not sure which “what” he means so I shake my head. Ric turns toward the living room, takes one step and then turns back to me. Side two of Rapture is coming to an end, again. Anita Baker’s howl-searching something about the way you-u… the way you live… the way you live your life. Ric says, “All spring Terrance asking if he could come to Chi for the summer and work for the family, you know, ‘drive a truck.’” I don’t know why he makes the finger quotes around “drive a truck.” Then, “Man, can you imagine Terrance pulls some shit like he did with the rent on my pops?! Nooo buddy.” Shaking his head, he turns around to walk toward the living room and I assume he’s going to flip the record over again. But after two steps Anita Baker’s take it easy, you better, better take it easy ricochets down the hall and, as if on cue, Ric turns around and steps toward the bedroom. I hear him whisper “damned straight” as he walks past me and through the door and turns left into the room. I’m not sure if he was talking to me or to himself, talking back to the record, to Terrance and the finger-quote “truck,” or to the Porsche he’s saying he’s getting. But I’m wrong. It’s none of that. Turns out it’s about how pissed he is or isn’t. Turns out it’s “is.”

A few seconds later Ric passes across the open doorway holding Terrance’s Raleigh Technium road bike over his head. Holding up the bike he disappears past the doorway to the right and I run the few steps to the door. I hear myself think, “oh-shit.” I look to the right and see Ric, all in one motion, turn to the side, step one foot through the sliding doors, and heave the bike to his left and over the railing. Ninth floor. The whole-ass Raleigh Technium road bike over the edge. When he turns back around Ric’s wipe-clapping his hands together and making that frowning-certain face you make when you’ve just finished a solid and sensible task. A job well done. When I hear the soft smash of metal down below I’m still hesitating over a shocked cloud of what-ifs: what if the bike doesn’t clear the sixth-floor balcony below; what if someone’s walking on the sidewalk at the wrong time; what if the fucking cops the fucking cops the fucking cops? Untouched by these what-ifs, Ric looks up to me:

2:45 A.M. SEPTEMBER 2, 1986.

My plan is to use this thin futon as a bed for the year. Almost as much a padded rug as a futon, it fits perfectly in the corner of this small room between the outside wall and the path of the door that swings in from the hallway. In the morning I can roll it back up and slide the folding door open to the living room. That’ll expand the space. Plus this corner stays dark despite the yellow light that, even with the blinds closed, spills through the window at night. Classes start tomorrow, well, today, and I still need to register, but I’ll start thinking about that when it’s really tomorrow. I can’t get to sleep with the last twelve hours whirling in my arms and legs and that smug-ass sheriff in my face at the door when I close my eyes and Ric talking to him over my shoulder like he’s laying down winning cards in a poker game we’d just found out we were playing.

The flight of Terrance’s Raleigh Technium road bike from Capitol Centre’s apartment #902 ends our first night on the balcony. After the bike leaves the building, even with Ric’s don’t-give-a-fuck-ism, we agree it would be wise to move inside. The spur of the moment ceremony of the bike’s exit also changes the air, or maybe it makes us notice all the changed air all around us all between us. Ric makes himself another glass of Stoli and grapefruit on ice. Inside the living room now everything feels like it’s leaning toward everything else. Yellow light from the street hazes across the ceiling. Ric sits down leaning forward with his legs wide apart and talking about when he gets married he’s going to sing “Ribbon in the Sky” at the wedding. He has no plans, understand, but, he says, he’s gonna sing it when she’s coming down the aisle. He’s been practicing. A closeness gathers around us. He says living beyond fifty is pointless; fifty years should be plenty. I notice a little yellow haze from the ceiling gathers and mixes in his bright, dark eyes. I don’t know about all that “should be plenty” stuff but fifty’s so far off it’s strange to even mention it. I say I’m not trying to sing at my wedding but it’s got to have music. He leans back at the kitchen table rotating his glass, looks up at me and asks what song I’d play to dance to, like for that first dance? I’m surprised to be talking about this at all, really, but I look away from him toward the window and, under the air conditioner, on the floor, Patrice Rushen still stares out from the cover of Pizzazz. So I say maybe “When I Found You,” which floats and then has that great breakdown at the end. Ric doesn’t remember that song but wants to hear that breakdown part.

So I take off Rapture and pick up Pizzazz. But when I turn it over “When I Found You” isn’t on there. Then I remember it’s on her earlier album Patrice. You know, Pizzazz–Patrice, it’s close. I’m saying how after “Forget Me Nots” in high school I’d bought as many of her previous records as I could find. And Now, too, with “Feels So Real,” which is up there with Niecy’s “Do What You Feel” and “I’m So Proud.” Come to think of it “I’m So Proud” might be a contender for the wedding-dance thing itself but, no, not quite. My fingers walk through the records and find Patrice. There it is: “When I Found You,” second song, after “Music of the Earth,” on side one. I put the record on, drop the needle, and catch the last breaths and congas of “Music of the Earth.” Then static in the pause before “When I Found You” comes on and, by the time the horns introduce the theme, soft, and I sit back down on the futon in front of the poster of the blown-away Maxell tape dude on the living room wall, the rest of all what’s been hiding behind the air is on its way out front. It’s like every inch of air in the room is invisibly tsunami-ing into every other inch of air in the room. Also it’s as if the room has somehow rotated 90 degrees inside itself like north is now east, east is now south and south has moved around to nine o’clock. And where the songs on Rapture start up close and then sear and search and tear out the walls while leaving them in place, “When I Found You” starts all up under your ear, whispering, and then draws all distance into this first closeness that really sounds like touch, I mean if you listen—or touch—close enough: a centripetal closeness; a gathered togetherness. The kind of closeness where the closer you get the further out—and back that togetherness extends. That’s when things like balconies and buildings and hemispheres start to rock back and forth.

Ric sits at the table, sips his grapefruit juice, and acts unimpressed. But he’s nodding his head up and down to the slow beat and shaking it side to side with the lyrics, I found love…and now I can say for me it’s a brighter day… When he turns his head my way his eyes are closed, brows up, which somehow opens his face wide. It’s like that; it sneaks up on you. Every time. If you’ve heard this song you know that the lyrics are feather light, riding on an easy rhythm, a soft rolling sea. Then the strings follow the saxophone solo and lift the song, lighter than before. It’s pure sweetness. But then toward the last minute, when Patrice Rushen repeats the chorus, held up by the strings, she pins the “me” in “for me” up an octave and then bends the line about “a brighter day” down into a minor key. The water darkens. This signals the beat to come back, doubled up at the start of like every fourth measure, and a little harder, more urgent, and the breakdown I was talking about begins. Now most people I know, and all the dudes I know, would have been talking about something by now and so the load of brick brought down by these subtle shifts in voice, by the beat inside the beat, and by the heat inside the dark, would get talked over. But Ric hasn’t said shit since the needle dropped. In the wedding fantasy, as it appears to me in this moment, this, when the water darkens, when the waves rise up, is where the families join in dancing—which should have signaled something about just what families are gonna be joining which dancing. But my mind’s too far behind all this to see any of that. So we can leave that for later.

In the living room of apartment #902 right now, with the song turned up and the air turned inside out and the walls drawn in around us and Patrice Rushen repeating Baby when I found… and twisting the You-u like she’s wringing out her next breath from the word itself, the word inside the word, Ric Williams rises up from his chair holding his glass in his right hand, left hand snapping and flipping twice with the double-first beat in those measures. “Oh, snap, yes, yes…” he says under his breath and slow-drags a two-step in a circle around the living room, dipping his shoulder forward like he’s headed out from the beach moving through the darkened waves. The song fades and the urge begins to hear it again, to feel it go over the edge, again, into the breakdown. Again. As I watch Ric dance his little dance and chop out that double-beat with his left hand, stepping out with his right foot when the high-hat closes, and while the backup chorus and Patrice Rushen trade repetitions of Baby when I found you, I know I’ve arrived somewhere I’ve never been. For all we know it’s a place that’s never been; maybe whenever something like this happens it happens for the only time. And again. Every time. And maybe one day this song will be about a wedding, a wedding inside some unrealized revolutionary rocking back and forth, but here and now it’s about a meeting, a friendship, an intimacy even closer than skin on skin. And it’s about the turned-inside-out, tsunami’d-ass-air in this living room—living room, I think suddenly—with some basehead’s burnt-blind eye in the carpet, in this ninth-floor apartment that’s but recently been vacated of a Raleigh road bike off its balcony.