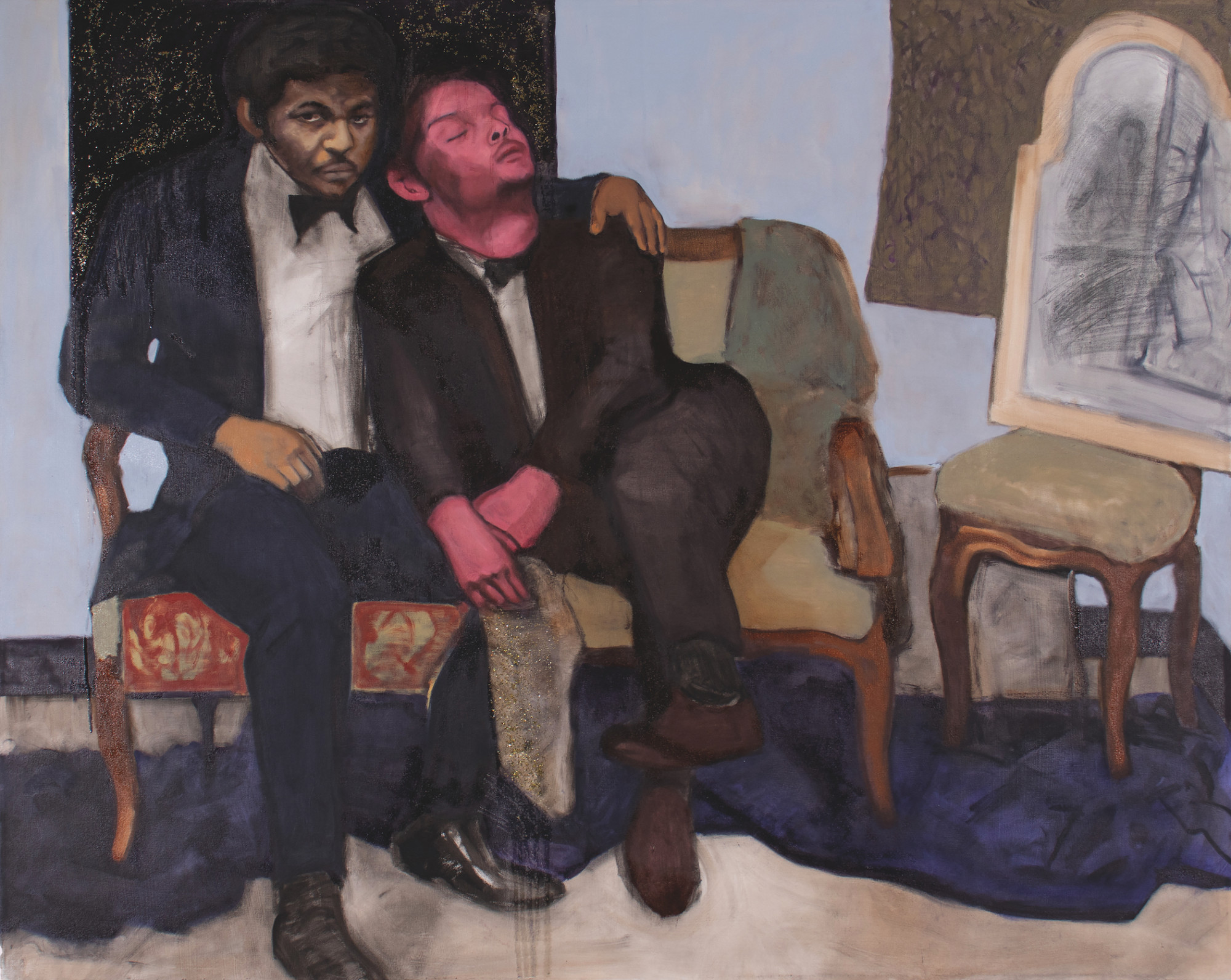

The Veil of an Intimate Whisper, 2023, oil and glitter on canvas, by London Pierre Williams. Courtesy the artist

Never Alone in the Night

The queer alchemy of Melvin Lindsey's Quiet Storm

By Craig Seymour

It happened at that “golden time of day,” as Frankie Beverly & Maze once sang, “when you find who you are.”

Weeknights at seven P.M., thousands of D.C.-area residents tuned their radios to WHUR-FM, Howard University’s commercial station, for the Quiet Storm, which consisted of mostly r&b ballads representing a kaleidoscope of emotions, from raw longing to cool resolve. This local program became a nationally duplicated format, with wide regional variations, and ultimately took such acts as Luther Vandross, Anita Baker, and Sade on a 450 SL Benz-ride to “Black famous” superstardom. But what’s lost in most accounts of the genre—which has become synonymous with formulaic “baby-making” slow jams—is the particularity of the original Quiet Storm and how it developed from the specific perspective of DJ/host Melvin Lindsey, a Black gay man.

I was seven when the Quiet Storm debuted in 1976. It began as the sound of the adults who controlled the stereo. But it soon allowed me to experience what neuroscientist Susan Rogers considers to be an essential purpose of music, how it allows us to experiment with identity. As she writes in This Is What It Sounds Like: What the Music You Love Says About You, songs allow us to “feel as if we are experiencing life through another person’s eyes.” Listening to the Quiet Storm, I could be a road-weary soul man ready for lifetime love (the Ebonys’ “It’s Forever”), a sophisticate narrating her husband’s betrayal (Nancy Wilson’s “Guess Who I Saw Today”), or a diehard race woman who’s finally had it up to here with her vain, no ’count boyfriend and his “Afro Sheen,” “afro clean,” “afro fluid,” and “afro do-it-to-it” (Marlena Shaw’s “Yu-Ma/Go Away Little Boy”).

The Quiet Storm also taught me that songs have a life beyond their original context. By putting different tracks in conversation with each other, a song that seems trite as an album cut might suddenly become a profound meditation on the human condition. It taught me about something else Rogers discusses: how individual listeners, and curators like DJs, are musical creatives in their own right. She says, “By perceiving, feeling, and reacting to the many dimensions of a song, a listener closes the creative circle and completes the musical experience.” Miles Davis even once told her: “Some of the best musicians I know aren’t musicians.”

As I grew older, many Quiet Storm songs spoke to my burgeoning awareness that I was different from guys like Billy Paul, who sang the passionate Black power love anthem “Let’s Make a Baby.” I had a secret, one I was scared to reveal to anyone, including myself: I was gay. Suddenly, songs I’d heard Melvin play for years acquired visceral new relevance. I fantasized about the escape of Randy Crawford’s “One Day I’ll Fly Away.” But I knew that wouldn’t solve my problems. Eleanor Mills told me, on a song by curatorial genius Norman Connors, “This is your life / not a game that you play.” I felt the urgency of Phyllis Hyman’s “Gonna Make Changes” and a push from Seawind to “Follow Your Road.” In time, I developed the strength to answer the call of Stephanie Mills to “Be a Lion.” I experienced this without knowing Melvin was gay. It now strikes me as odd that in all the historical accounts and celebrations of the Quiet Storm I’ve read, not one has considered how Melvin’s experiences as a gay man informed the songs he chose to play and how he put them together, crafting an aesthetic that has transcended generations and become part of the Faith Ringgold–style quilt of African American life.

STORM TRACKING

Though Melvin Lindsey is the name most associated with the Quiet Storm, he didn’t create it. That credit goes to media visionary Cathy Hughes, then WHUR’s general manager, now owner of Radio One, the parent company of TV One. She was inspired by her study of “psychographic” radio at the University of Chicago. “You learn who your audience is and what they are doing, and you fit your programming to fit their lifestyle,” Hughes says. “I had an overpopulation of unattached Black women who would love to be serenaded even if it’s just on the radio.”

Initially, the program, which took its name from the Smokey Robinson ballad that served as the show’s theme, was supposed to feature a rotating DJ lineup of Howard University communications students needing commercial on-air experience. But Hughes gave twenty-one-year-old freshman Melvin—a D.C. native who grew up listening to his father’s Frank Sinatra records and being a Beatles “fanatic,” as well as a disciple of Diana Ross—a shot as a fill-in for the Quiet Storm. She trusted him, not because he showed any particular talent at radio, but because he was already her paid assistant, picking up her son from school and bringing him to the station, where together, they’d all eat dinner, which Hughes prepped in advance each weekend.

In these earliest days, Melvin worked with fellow student Jack Shuler, a sound engineer responsible for steadily putting the needle on the vinyl and ensuring there was no “dead air.” The two were also, as Shuler describes it, “the best of friends.” It took awhile for them to get the Quiet Storm formula down. If they couldn’t think of what to play, they’d take requests. They also knew there were two acts that would always connect with the D.C. audience. He says, “We could always play The Isley Brothers and Phyllis Hyman.”

Melvin became known for his unobtrusive delivery, as he played multiple songs before breaking in with his steady, butter-roll-warm tone, reminding listeners they weren’t alone in the night. “The music spoke and then when he spoke, it fit,” says Dyana Williams, the radio legend once known as Ebony Moonbeams, who was a mentor to Melvin. “It was almost like he was part of the verses and the chorus and the melody and the harmony.” But Shuler says the lowkey approach that Melvin leveled-up to an art stemmed from the timidity of a twenty-one-year-old trying to find his way in life. “Melvin had nothing to say,” laughs Shuler, who returned to his Florida hometown after Melvin began helming the Quiet Storm on his own. “There was nothing loquacious about him at the time.”

Melvin’s popularity with listeners scored him a full-time slot, and the Quiet Storm with Melvin Lindsey became the sound of nighttime D.C., attracting fans across the social spectrum. “I got a letter from Lorton [Correctional Complex] signed by 196 inmates, saying how much they liked the program,” Melvin said. “It really touched me.” He promoted the work of hometown artists such as Parris, responsible for the gripping, soap-opera-like “Can’t Let Go”; Starpoint, a Maryland group that balanced electro-funk with lush ballads such as “This Is So Right” and “Till the End of Time”; and the Howard University Jazz Ensemble, which produced the almost operatic declaration “Loving You Has Been an Ecstasy.”

The Quiet Storm hit D.C. when Black people were asserting a new political voice focused on self-governance in the nation’s capital, which had been controlled by Congress until the Home Rule Act passed in 1973. Particularly significant was the 1979 mayoral election of Marion Barry, the son of Mississippi sharecroppers who came to D.C. to fundraise for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Barry’s campaign was linked to the growing political power of D.C.’s gay community, which played a significant role in his victory. He pledged in 1982: “Some people claim that San Francisco is the capital city for gays. Well, we’re going to change that and make Washington, D.C., number one.”

The Washington Star called D.C. the “Emerald City of live-and-let-live tolerance for homosexuals,” and the Quiet Storm was accepted into the most intimate spheres of gay life. A columnist in the gay weekly the Washington Blade noted in 1979: “Most singles I know can be found at home…weeknights, listening to WHUR.” The program even made its way into personal ads. A white man wanted to “create a quiet storm” with a white or Black man, 35–56, who loves “movies, theater, short travel trips, swimming, and more.” And a woman of unspecified race sought a Black gay woman, “cocoa-colored (or close enough); drug, alcohol & child free; gainfully employed; w/ a sense of humor, some wit, common sense;…a DC resident; reasonably discreet but willing to return a quick kiss; a light-to-non-smoker; [and] an avid Quiet Storm fan…”

One gay listener wrote to the Washington Post that the Quiet Storm helped him cope while his lover was ailing: “In 1985, when my companion was living with AIDS, it was Melvin Lindsey’s program…that helped us deal with our own quiet storm.”

Gay people heard things in Melvin’s music that wouldn’t necessarily be evident to those unfamiliar with the codes of being “in the life.” “Chile, you know he was playing those songs that had double meanings,” says lifelong Washingtonian and LGBTQ+ activist Rayceen Pendarvis. “He was giving, ‘I’m gonna tell y’all a story, and the gays will perfectly understand what I’m talking about.’”

Melvin Lindsey at WHUR with Teena Marie, by Oggi Ogburn © The artist

MELVIN’S MELODIES

“I have to prepare for each show,” Melvin told the Post. “I go through my older record collection and pick out tunes I think would be appropriate for that evening. Then for the next five hours, I sort of spontaneously play records, taking requests from the audience and using my own judgment.” His selections reflected his moods. “My listeners at this point know that, say, Melvin’s feeling good today, or Melvin had a bad day.”

While he seldom discussed his sexuality publicly, it wasn’t much of a secret to those around him. “Melvin was a private person,” says Dyana Williams. “It wasn’t that he was denying his sexuality, because his friends knew.” Melvin was also accepted within Black lesbian and gay circles. “He didn’t have to have a rainbow flag on,” says Pendarvis. “He represented us in his excellence. And the community covered and protected him.”

The details Melvin did reveal about his personal life suggest ways to understand the music he offered each night to his fans. “It was the ’70s and early ’80s…and [I was] running around, and just doing whatever,” he said. “From the period of 1985 on, I bought condoms every time I went to the grocery store.” Many Quiet Storm staples reflect the lure of fleeting encounters and the yearning for something more. Chaka Khan, with the band Rufus, pleads, “Send me a stranger to love.” Brenda Russell propositions, “Let me hold you tight / If only for one night.” The Isley Brothers, on “Love Put Me on the Corner,” testify about sleepless nights, “walkin’ up and down the streets / My heart is aching down, down to my feet / I’m looking for someone to love.” And on “Daybreak (Storybook Children),” Cheryl Lynn sings of the heartbreak that sometimes comes after an evening of pleasure and connection: “How can I ever leave this place beside you? / You were the only one I ever cried to / The night is through.” These sentiments “hit different” for lesbians and gay men who are often pressured to live their entire romantic lives in secret, who feel the sting of 21st Century’s “Does Your Mama Know About Me?” and the ache of Patti Austin singing on Quincy Jones’s “Love Me by Name.” They hit especially different for the generation that came of age at a time when the dreams of the Gay Liberation Movement were often deferred by the realities of the day-to-day straight world. Black writer Hilton Als, who came into gay life around the same time as Melvin, described his friends as “romantics who never loved.”

Indeed, there’s something “queer” about the whole nighttime world that Melvin orchestrated with his music. I’m using “queer” in the way it developed in academic and activist circles in the ’90s as a way to refer to a range of sexual expressions that don’t neatly conform to the conventions of “lesbian” and “gay” (which historically have been associated with whiteness) and don’t necessarily relate to mainstream prescriptions of lifetime companionship. Melvin empathized with the “Children of the Night” that the Jones Girls sang about, those who “walk the shadows…looking for some company.” He understood the “Night Games” that troubled Stephanie Mills, because “searchin’ to find someone new isn’t easy.” And I can’t help but think he was revealing a bit of himself, sitting alone each evening in the radio booth, when he played Norman Connors’s “You Bring Me Joy,” sung by Adarita (Ada Dyer), with its lyrics, “I’m so lonely at night / And I’m mixed up again…”

IT’S SO HARD TO SAY GOODBYE TO YESTERDAY

Melvin’s father knew something was wrong with his child. Each afternoon, William Lindsey stopped by Melvin’s place to chat about this and that. But on a spring day in 1990, he could tell his son, on the verge of turning thirty-five, “was very upset,” though he wouldn’t learn why for some time. William remembered: “He said it was the worst day of his whole life.…I could see the change.” Shortly before his father’s arrival, Melvin received news that a biopsy done on a purplish spot on his nose showed he had Kaposi sarcoma, a form of skin cancer that can result from a weakened immune system. He understood exactly what this meant, as he called a friend and confessed amidst a squall of tears: “I have AIDS.”

The news came as Melvin was at a career peak. His smooth style and suave looks helped him score a gig co-hosting (with Angela Stribling) BET’s entertainment magazine series Screen Scene. He was also making one million dollars over five years at WHUR competitor WKYS. But things began to change once people around town started noticing the discolored patches on his face and arms. In November, his contract wasn’t renewed with WKYS after negotiations went stagnant. One year later, he got a gig hosting a Saturday morning show on another D.C. “urban contemporary” station, WPGC, for a sum the Post reported as $100/week.

By this point, Melvin’s health struggles were an open secret in D.C., and on March 18, 1992, the Post profiled him on the front page of its acclaimed “Style” section, where he discussed being gay and revealed how AIDS had brought him closer to his family. He told his brother and sister first that he had AIDS, sitting out on the porch after he’d returned home from being hospitalized for a high fever. “It was a big shock,” said his older sister, Brenda Lindsey, “but we were just all there for him.”

He made plans to tell his parents the following day. But he wasn’t expecting what happened once they arrived. “This is the most important moment of my life,” Melvin said, “and my mother comes in here with all these delicatessen meats: pastrami, corned beef, ham.” He told her, “Momma, let’s sit down and talk.…Momma, I have AIDS.” She responded: “Oh, baby,…they told me already.”

His father approached caregiving by way of scripture: “Embrace a person with a holy kiss.” He would press his lips against Melvin’s forehead and on his son’s folded hands. Melvin welcomed this tenderness: “I don’t remember him kissing me as a kid at all, or even spanking me as a kid. His sensitivity makes me feel good.”

Following the article, Melvin returned to WHUR for one more show. He broadcast from his bed at D.C.’s Sibley Memorial Hospital. He showed gratitude to his devout listeners, as he’d done when he left the station in 1985. Then, his last song was Gladys Knight and the Pips’ “Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me.”

Melvin died, at thirty-six, on March 26, 1992, four days after D.C. heard his voice live on air for the last time. His homegoing took place the following week at the Howard University Law School Chapel. Fans across the D.C. metropolitan area came out to show love and say goodbye. “I remember his funeral,” says Pendarvis. “First of all, I had to get up two hours early because I knew it was going to be packed. I had to get a seat. I was not going to be standing up. But I knew that I had to pay respect to a man who created a legacy, who touched my life and touched so many other people’s lives.”

One of the singers offering musical tribute to Melvin was Jean Carne, who epitomizes Melvin’s Quiet Storm aesthetic for the way she moved from making avant-garde jazz with her ex-husband, Doug Carn, to crafting “grown,” reflective soul. She performed a medley of some of Melvin’s favorite songs, including Donny Hathaway’s “Someday We’ll All Be Free” and “For All We Know” and the Cooley High tearjerker by G. C. Cameron, “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday.”

In the years since Melvin’s death, the term “Quiet Storm” has become used so widely throughout criticism and social media and radio that it’s almost lost its meaning. Revolt once, in a head-scratching move, called rapper/singer Drake “a game-changer of the Quiet Storm genre.” But more bothersome to me—a Black gay man whose deepest longings were expressed in Melvin’s selections—is the way people mention his work and sexuality without considering how the two are inseparable. Melvin’s coded musical choices are no less related to his identity as a Black gay man than Aretha Franklin’s anthems about emotional equity are related to her identity as a Black woman. Also, by being early adopters of certain songs that have become widely cherished totems of Black love, Melvin—and his queer listeners—show how queerness has helped shape Blackness. To riff off the O’Jays, there’s a message in the music.

Nocturnal Bliss: A Quiet Storm Playlist

I created this playlist as a celebration of the legacy of Melvin Lindsey and the impact of the Quiet Storm. By showcasing the sultry grooves that helped so many of us to find our melodic nocturnal bliss, Melvin created something that until then didn’t exist on the radio. He highlighted soulful ballads that told stories, and provided the soundtrack for falling in love, falling out of love, and falling in love all over again. Melvin enabled us to discover singers and musicians who were not topping the charts nor in regular rotation on the airwaves. He helped to create new fans who would often develop a desire to explore these recording artists’ catalogs and experience them live in concert. The sonic ambiance he curated during those late hours motivated us to listen every night with our cassette tapes ready to record. While those homemade recordings have faded or gotten lost over the years, our memories remain vivid. I am thankful to have been able to tune in for Melvin Lindsey and the Quiet Storm experience.

Love,

Rayceen Pendarvis