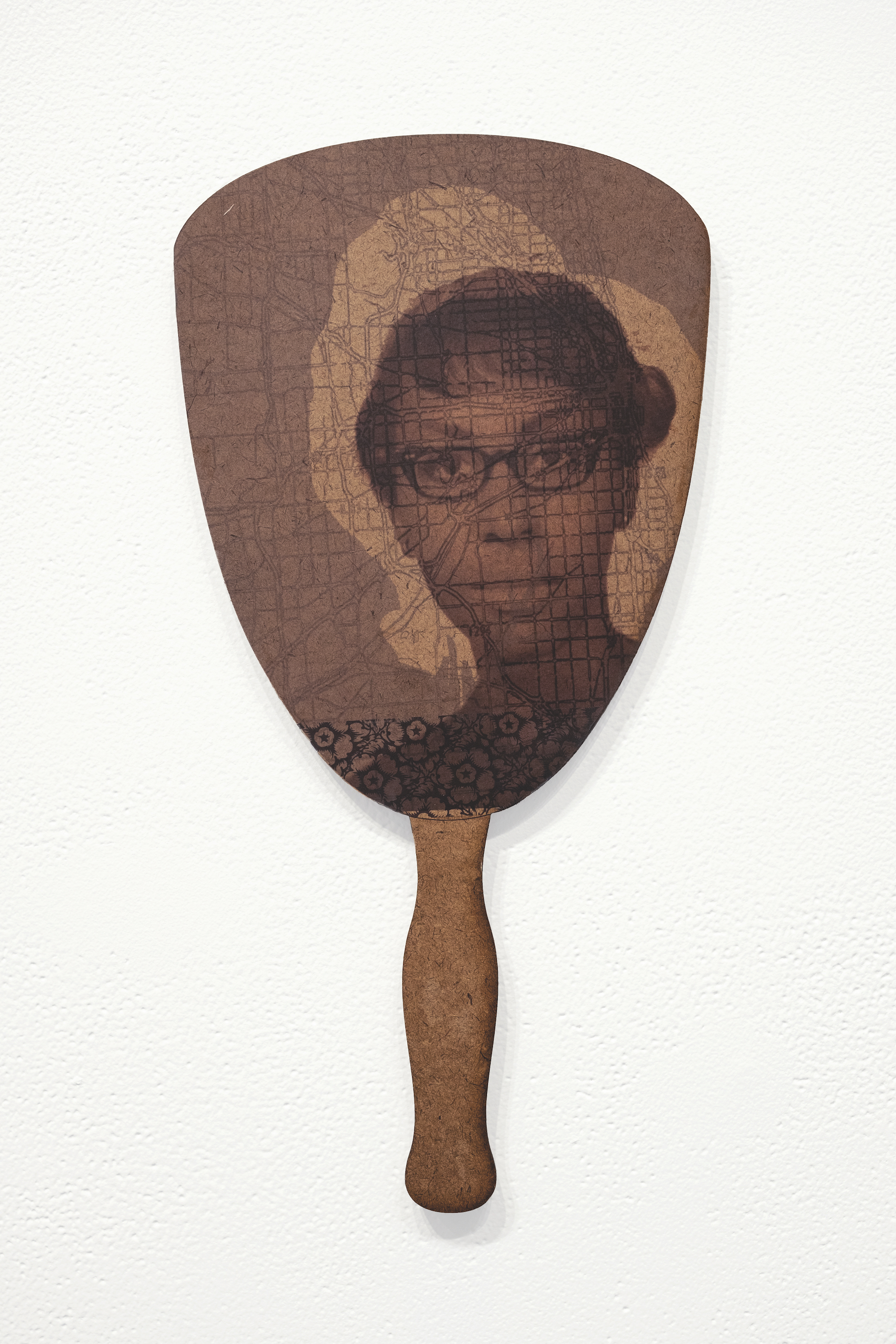

A photo of Tammie Rubin's work. Courtesy the artist

Tammie Rubin’s Counter-Cartography

The artist reclaims truths and lives, lost and forgotten

By Tyler Isaiah Campbell

In her book A Map to the Door of No Return, the poet Dionne Brand describes the act of “sitting in the room with history.” She writes: “One enters a room and history follows; one enters a room and history precedes. History is already seated in the chair in the empty room when one arrives.”

I felt as if I were “in the room with history” in January when I visited Points of Origin, the latest exhibition from the Texas-based, Chicago-bred artist Tammie Rubin, which was on view at New York’s C24 Gallery through March 8. The first things that caught my eye while walking through the exhibition were the many blue-hued ceramic cones that lined the gallery. The works, which together are titled “Unknown Ritual Masks,” are enthralling. Are these supposed to represent what I think they are? I thought to myself.

Some of the masks are adorned with rectangular ornaments, others vibrant designs, and all with the same hollow, empty eyes. They are as discomforting as they are stunningly intricate. Each bears a stark resemblance to the pointed, hooded masks worn by members of the Ku Klux Klan who moonlight during work hours as our school teachers, our police officers, our politicians. The closer I got and the longer I looked, other coned-shaped objects came to mind: neon orange traffic cones, SpongeBob’s whimsical best friend Patrick Star, traditional West African headdresses, the iconic Harry Potter sorting hat, and so on. Disarmingly layered, these sculptures, like much of Rubin’s work, are challenging to look at because they resist legibility, which is to say they cannot be reduced to any singular “right” interpretation, and like Blackness itself, they thrive within and because of their ambiguity.

Black artists must routinely contend with the pervasiveness of the white gaze within their works. That gaze seems to require they produce work that tells us something about racism or the legacies of slavery or the violence brought against Black bodies etc., etc. What makes Rubin’s work profound and necessary is her capacity to foreground the fullness and breadth of the lived experiences of Black people in America while simultaneously not diminishing the racialized terror in our collective past and in our present. Both Black livability and anti-Black terror exist in the room together.

Rubin’s work is perhaps most recognizable by her glazed porcelain and stone ceramic sculptures like “Unknown Ritual Masks,” which are part of a larger ongoing series Always & Forever, (forever, ever). But for my money it is her innovative (de)construction of the map in works like her plotter ink drawings and Masonite renderings of everyday objects that are the most indelible.

It's All Ahead, 2022, masonite collage by Tammie Rubin. Photographed by Hector Martinez. Courtesy grayDUCK Gallery

Rubin and I share Southern origins as descendants of formerly enslaved people who moved to the North for refuge and the false promise of a better life. It was after the lynching of my great-great-uncle somewhere in Virginia, where his blood still stains the trees, that my ancestors had to uproot in the dead of night and head north, where they eventually settled in my native Philadelphia. This is all I have been told of my family’s forced migration story. The gravity of certain traumas renders them unspeakable. Yet Rubin’s work invites me (and appreciators of her work) to consider how we might reimagine and remap our familial legacies.

Maps are ostensibly two-dimensional instruments of navigation that many of us probably don’t give a second look to, unless we are tracking the distance to our destination on tiny back-of-the-seat monitors on airplanes or looking for the nearest coffee shop in an unfamiliar part of town. But no map is innocent. They are monuments of colonial power and domination, mechanisms of erasure and displacement. Yet in the carefully guided hands of Rubin, maps are tools of recovery and testaments to the radical potential of community across borders.

Consider, for example, her Masonite collages that are shaped to resemble hand-held prayer fans like the ones I grew accustomed to seeing during my childhood at church, waved vigorously back and forth by my sweet Grandmomma Wilma and her friends who were, of course, always dressed in their Sunday best. Rubin takes an object that otherwise would be decidedly mundane and imbues it with capaciousness. The fan titled “It’s All Ahead” features an old family headshot of Rubin’s mother—Queen Esther Rubin—superimposed against a brown, almost skin-colored map of her Southside Chicago neighborhood. There are visible lines that delineate forgotten neighborhood borders, making legible that which is unseen. The detailed lines on Rubin’s maps show us a way forward by following the breadcrumbs of where we’ve been.

Tammie Rubin is not only a ceramist; she is also a counter-cartographer. Her practice is a form of counter-mapping meant to upend narratives and write into history those who have been left out, overlooked, or erased altogether through the violence and historic displacement of Jim Crow, red lining, and modern-day gentrification that would seek to restrict the movement of Black people. Whereas Columbus set the precedent for mapping geographical terrain as a weapon, Rubin disrupts and subverts this process by using maps as vehicles for reclamation, as a mirror of hybrid Black literacies, the genesis of worlds yet to come.

Tammie Rubin is a sculptor and installation artist whose practice considers power objects, coded symbols, Black American migration, citizenry, rituals, and magical thinking. Rubin employs ceramic conical forms, raised maps, and murals to create spaces of metaphysical, physical, and spiritual escape. Using imagery and objects of the familiar, she contemplates ideas of authenticity and inherited meanings while inviting new considerations that open dream-like spaces of unexpected associations and dislocations.