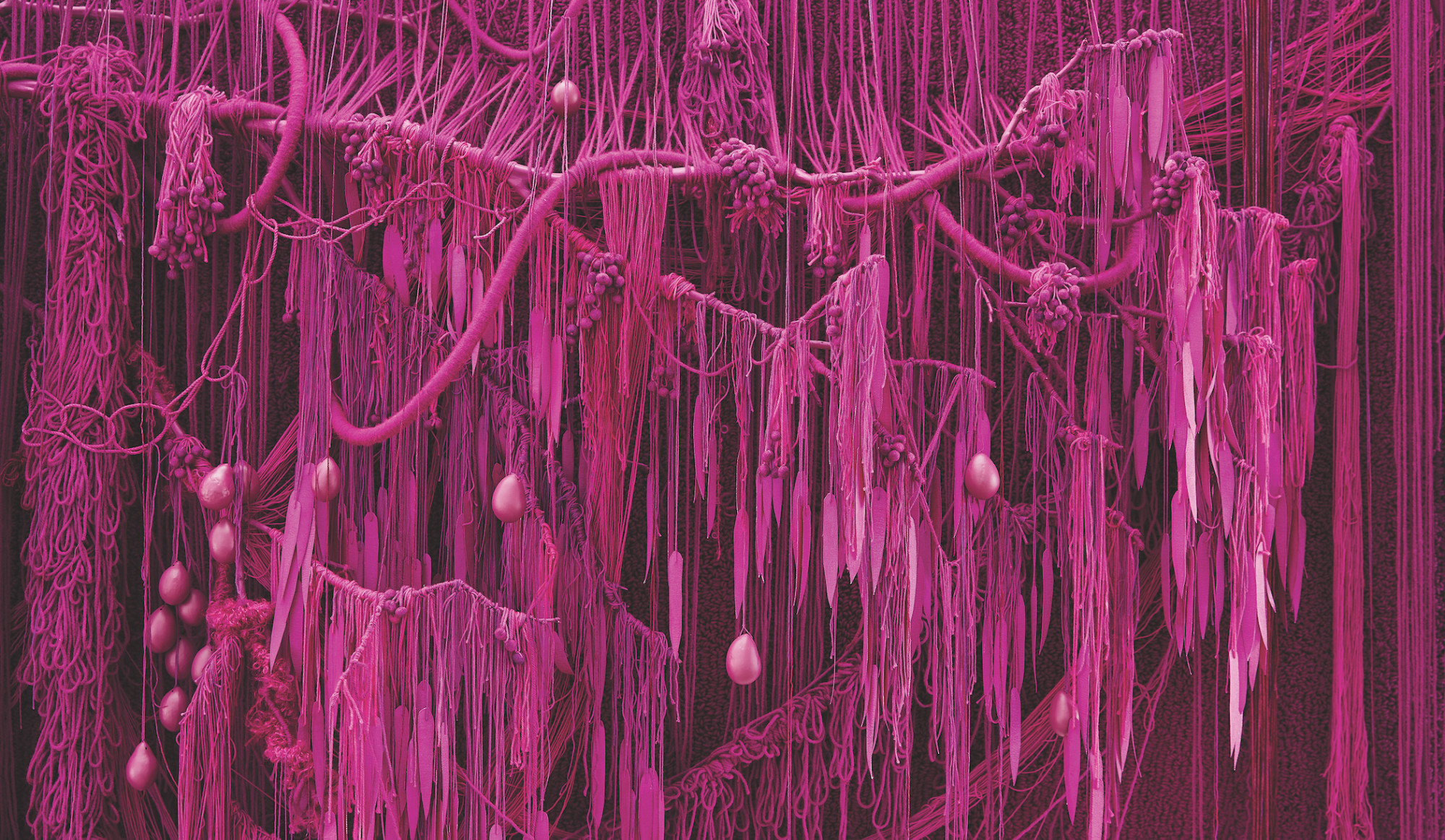

I Eat the Stars (detail), 2021, hand-dyed wool yarn, wool felt, tree branch, canvas, paint, and mixed media. Photographed by Russell Kilgore. All artwork courtesy Sonya Yong James and Whitespace Gallery

The Threads of Time and Place

Sonya Yong James creates monumental moments thread by thread

By Beth Ward

Sonya Yong James assembled I Eat the Stars from felt and tree branches. The textile installation, hanging thirteen feet by four feet, drips with hand-dyed yarn in a riot of magenta.

The color came to James in a fever dream, she says, one brought on by a 104-degree temperature during a bout of COVID—a hue so saturated and intense that staring into it made her sweat, made her dizzy. James thought of death as she built the piece, her death, working the yarn and wool felt in a kind of neon delirium.

“[That piece] did exactly what I wanted it to do,” she says, “which is to create almost a hallucination. You could stand in front of that thing, and it was uncomfortable. The color was so out of control.”

It’s true. To look at I Eat the Stars is to experience near-vertigo, the depth of color dragging you down, pulling you in, as your eyes struggle to focus. But the closer you get, the more it reveals itself. Tucked between strands of roughly 20,000 yards of yarn sit tiny animals, hidden and peeking, wolves and owls painted in that same violent magenta. You are in another world now, they seem to say. A portal has been passed through.

James’s most recent exhibition, The Pleasure Was All Mine, showed at Whitespace Gallery in Atlanta in late 2023 and also featured transportive works.

In Signs and Wonders (1997 and 2022) (with A and S) (Mexico City)—a large-scale installation made of hydrocal plaster hands, ceramic anatomical hearts, feathers and florals, snakeskin, wishbones, linen, and crow’s wings—James pays homage to Mexican milagros.

Milagros are quarter-sized religious folk charms often used to invoke spiritual petitions or to increase luck, but James’s charms are not the size of coins. They’re the size of clenched human fists and arched feet, bird wings opened full-span, flowers not in bud but in bloom. The ceramic hearts held wishes and hopes inside, James tells me, ones she wrote on paper and tucked in, ones that burned like an effigy when she fired the clay.

I Eat the Stars, 2021, hand-dyed wool yarn, wool felt, tree branch, canvas, paint, and mixed media, 13'x4'x18". Photographed by Russell Kilgore

Milagro means “miracle,” and indeed, the piece becomes a sort of altar as the viewer stands before it, every cast hand a kind of votive. Hanging just above eye level on the brick wall of Whitespace, sunbeams shattering across its surface from a skylight in the ceiling, Signs and Wonders turns the front room of the gallery into a small cathedral. You gaze up just slightly, feeling like a supplicant.

For Snake Charmer (October 31) (Day of the Dead) (with S) (Oaxaca), James cast 108 snake vertebrae in porcelain. Using wool thread, she manipulated the bones onto a metal hoop not much larger than an old wooden spinning wheel. That number is sacred in Dharmic religious traditions and represents, among other things, the distance between our bodies and God.

So much of James’s work is like this—haunted and fairytale-like, imbued with hidden magics, layered with mystery and meaning. The sculptures and installations often hang in freefall, their threaded tendrils weighed down by beads and scavenged bones, roots and woven hair, coyote teeth and ash. When James speaks to me about them, it’s in a lower register, her voice deep and breathy, an almost-whisper, as if we’re sharing a secret.

I perhaps felt this eeriness most acutely standing in front of James’s Spirit is a Bone at the Marietta Cobb Museum of Art in early 2023—a wall-to-wall installation twenty-four feet long by six feet tall. The piece drips vertically with strips of handspun bedsheets, wool, and linen, all hanging in soft shades of ivory, beige, white, and cream.

In Korean culture, white is a color associated with death and mourning, and its use in the installation makes the piece feel like an invitation across the veil. Stirred by the humming of the vent in the ceiling, cold air blew down and teased its threads, making them dance as I walked along the wall, taking it in that spring afternoon. A specter, it seemed, was moving through the piece with me.

James is a Knoxville-born multidisciplinary artist working primarily in textiles, and her work feels very much in conversation with that of fellow Southern artists Hannah Ehrlich and Zipporah Camille Thompson. I get a sense of her, too, in the nature-inspired textile work of Portuguese artist Vanessa Barragão and the knotted, woven sculptures of Tanya Aguiñiga. The later work of Sheila Hicks faintly echoes through James’s sculptures and installations, and Claire Zeisler’s influence can be felt, too.

But it’s the otherworldliness of James’s art, the felt presence of something truly esoteric, that makes it entirely its own.

James graduated with a BFA from Georgia State University, where she studied under the late Larry Walker, the father of legendary visual artist Kara Walker. James has shown her work across the South, with exhibitions at MOCA GA, the Ogden Museum of Art in New Orleans, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts. Her art is held in esteemed permanent collections in countries as far away as Belarus and Mauritania.

James spoke with me via email, and on a frigid morning in early December, I visited her Atlanta studio, a brick-walled space packed with jars of snake bones, tufts of leftover thread, bins heaving with spools of yarn, and books like Taschen’s Astrology, Fashioning Felt, and the Encyclopedia Anatomica stacked and teetering. We sat at a makeshift table made of plywood, in the shadow of a towering twelve-foot loom, and talked about her work, about tenderness, and about textiles as a conduit for memory and landscape, touch and time.

Beth Ward: I’d love to hear a bit about your background. How did art find you?

Sonya Yong James: My parents met in Korea during the Vietnam War, and they moved to my father’s hometown of LaFollette, Tennessee. He went to the University of Tennessee, and then they moved here, to Stone Mountain, Georgia. So, I grew up here.

Art was always a part of my life. But as a child, I wanted to be a musician. Somebody gave my mom an organ, and I started learning how to play the piano on the organ. Then this really nice lady had a beautiful upright Steinway grand piano that she had gotten for her children some forty years before, and she gave us that piano.

I wrote music. I was playing Debussy, Beethoven. I even played violin for a while. My mother, it being the Deep South, she also knew someone that made dulcimers. I would place it on a surface and play that.

But the thing is, I was extremely shy. It was really hard for me to perform. I would do recitals, and I would look out at all the people, and the whole entire sonata would just leave my head.

Also, with the writing of music, I didn’t hear the music as much as I saw it. So, around the age of fourteen, I became serious about making a decision—do I hear, or do I see? What’s my life gonna be? And I said, “Oh, I see.”

Having a bit of a solitary childhood, art would also be something that would keep me company. I collected things in nature, came up with crazy little dyes in plastic bags, made strange little objects out of leftover textiles at the house for no good reason.

I’ve always followed my hands in that way.

Do you see that in the way you work today?

I do have a prescribed way of working and thinking, but that’s also mostly intuitive. The show that I just had at Whitespace? I had a real clear idea in my mind’s eye how things were going to look, and I got really surprised by [what it became].

And I’m okay with that. Because I can only impose so much of myself on things, on materials. And then I just have to let them dictate what they want to be.

Signs and Wonders (1997 and 2022) (with A and S) (Mexico City), 2023, ceramics, raku, hand-spun and hand-dyed yarn from loom waste, hydrocal, linen, vintage feather flowers, crow wings, pheasant wing, wish bone, snake skin, snake bones, and mixed media, dimensions vary. Photographed by Chris Carder

What draws you to textiles as your primary material?

After I was a musician, I thought, “Oh, I’m a painter.” There just seemed to be some sort of gravitas, some sort of, “Oh, that’s where the canon is. That’s where history is.”

But I love textiles, I love cloth, because they’re ubiquitous materials, and they’re something so central to the human experience. Cloth is always touching us. I’ve been using bed sheets [in my sculptures] for about seven years now. We’re born in bed sheets. We live in them, and we dream in them, and we sleep in them, and we heal in them. We’re sick in them, and we die in them often.

Using old textiles, they hold the memory of the body, of the human being that they belong to. Clothing, too—especially ones that are vintage or antique. They’re really beautiful, but sometimes, they are a little abject, right? Sometimes people’s hair is still on it. Sheets, clothing, sometimes they can still smell like people.

Can you speak more about charged materials? What does that mean for you? What does a charged material add to the work?

I like how materials can hold the memory of time and place; something like wool felt. I like the idea of wool felt because it holds the memory of the animal. You can tell the health and the happiness of the animal, the way it was cared for, what it ate. A really healthy sheep has beautiful wool that’s been taken care of.

But then also, too, there’s a kind of hidden energy in wool felt. Because I’m imposing myself on it. It’s a lot of water, and friction, my hands rubbing it over and over and over again, sometimes tens of thousands of times. I like how it holds that energy of me.

Whenever you stand in front of a textile—something about textiles is tender to me. They’re soft, pliable. They can evoke the feeling in the viewer of their own fragility, because there’s something about them that feels a little fragile. I feel like they might evoke in the viewer the idea of their own vulnerability.

And really, their mortality—that’s the thing I’m touching on.

The idea of looking at something that’s made out of textiles is a very different feeling than standing in front of a monumental metal sculpture. Like Richard Serra; you look at that and…talk about imposing your will. On metal? That takes a lot of energy, a lot of heat, a lot of strength to really impose yourself as a human being on [material] like that.

Standing in front of a piece work that’s made out of textiles, you think of your mortality, but standing in front of a work that’s made out of metal, you realize that it will live longer than you.

You’re often considering memory, the passage of time, nostalgia in your work. What about these ideas most compels you in terms of translating them into sculpture?

In the work that I make, or even the way that I title shows or pieces, I like to keep things ambiguous and open.

I did a talk at this past show, and people were very fascinated by the yellow piece [All the yellow leaves], which I appreciated very much. But seventy-five people were looking at me like, “Tell us more. Tell us more.”

I had already talked quite a bit about it, and there’s this part of me that’s like… “I don’t think I can [tell you more].”

I remember seeing [artist] Louise Bourgeois in a documentary, and I was in that situation [with the question], and I remembered where she says, “I’ve already done all of the work. I’ve already done my part. Now it’s your turn to do the rest.”

Is it important to you for the person looking at your art to know what it means to you?

Not necessarily. I would never want to be so didactic. That kind of work is not very interesting to me—“This is what this is. This is what this represents. This is how I want you to feel. This is how I want you to react to it.”

You mentioned Louise Bourgeois. Who are some of your other artistic influences? Whose work inspires you?

I love the textile work of Louise Bourgeois for its emotion and its visceral, corporeal quality, Korean artist Do Ho Suh’s large textile installations of recreated homes, and Chiharu Shiota’s thread installations.

I’m influenced by so many things every day. I’m currently reading Faith, Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan, which is filled with thoughts and questions about belief, freedom, grief, and love. Words, poetry, and prose really have an impact on my work. Sometimes the words come before the actual sculptures do.

Spirit is a Bone (detail), 2020, hand-spun bedsheets, wool, linen, cotton, coyote teeth, crow bones, dog ashes, and mixed media, 24' x 6' x 18". Photographed by Beau Gustafson

Do you see your work as being inspired by or in conversation with any kind of larger lineage of Southern textile artists?

I really admire the hand-woven textiles of Southern Appalachia, ones from the past two centuries that are often referenced as quiet and unseen work. I love the care and pride it takes to not only make something of utility like a towel or linen, but also the woven coverlets and quilts as well.

This tradition of Southern textile artists and women in the South—it was really out of necessity that they did the work that they did. It’d be scrap cloth they’d use to make the quilts, these really humble, leftover materials they’d use to weave their coverlets. They dyed it with natural materials that they found, like walnut hulls.

There’s a part of me that really likes that. I throw away nothing. I have piles of leftover threads, and they will become something. That heart sculpture? That was handspun yarn out of loom waste. I’m always wanting to honor the materials, not cast them away, hold on to them.

What I find interesting, too, is the tradition of bojagi. I love this. This is a Korean textile tradition, and it looks like quilting. You take scrap pieces of material that you don’t want to throw away, that you want to keep, and you sew it all together. And it’s often in a square.

Koreans believe that if you cover something and wrap it in cloth, it protects you. It brings you good luck. So, it’s almost like, “Ah, no wonder I like to wrap things, to hide things [in my pieces].” Maybe it’s just inside of me, that Korean tradition.

I’ve also recently been looking again at the song “In the Pines,” a traditional folksong from Southern Appalachia traced back to the 1870s. It has been [popularly] attributed to the musician Leadbelly but is thought to have come from immigrants from the UK. I’ve been listening to Loretta Lynn’s version. I believe this could inspire a new show or body of work.

You’ve also mentioned that your work has been described as Southern Gothic. Does that feel true to you?

Kind of, yeah.

You saw the white piece [Spirit is a Bone, 2020]? Well, I did a really crazy black piece, too, that was a landscape. It was all these sort of vines. It was all black, with these big willows. It looks pretty funerary. The title of it was I know a song of the place where I live. Does it know a song of me?

To me, that really feels like here in a lot of ways. Charged. The Deep South is a really charged place. This land, it holds so much memory.

Sonya Yong James lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia, and is a multidisciplinary artist who works with thread and repurposed cloth for the references that they hold such as mending, repairing, and connecting. James has exhibited nationally and internationally for the past twenty years and has an upcoming residency in Mexico City. Her current work speaks to a fascination and reverence for the natural world.