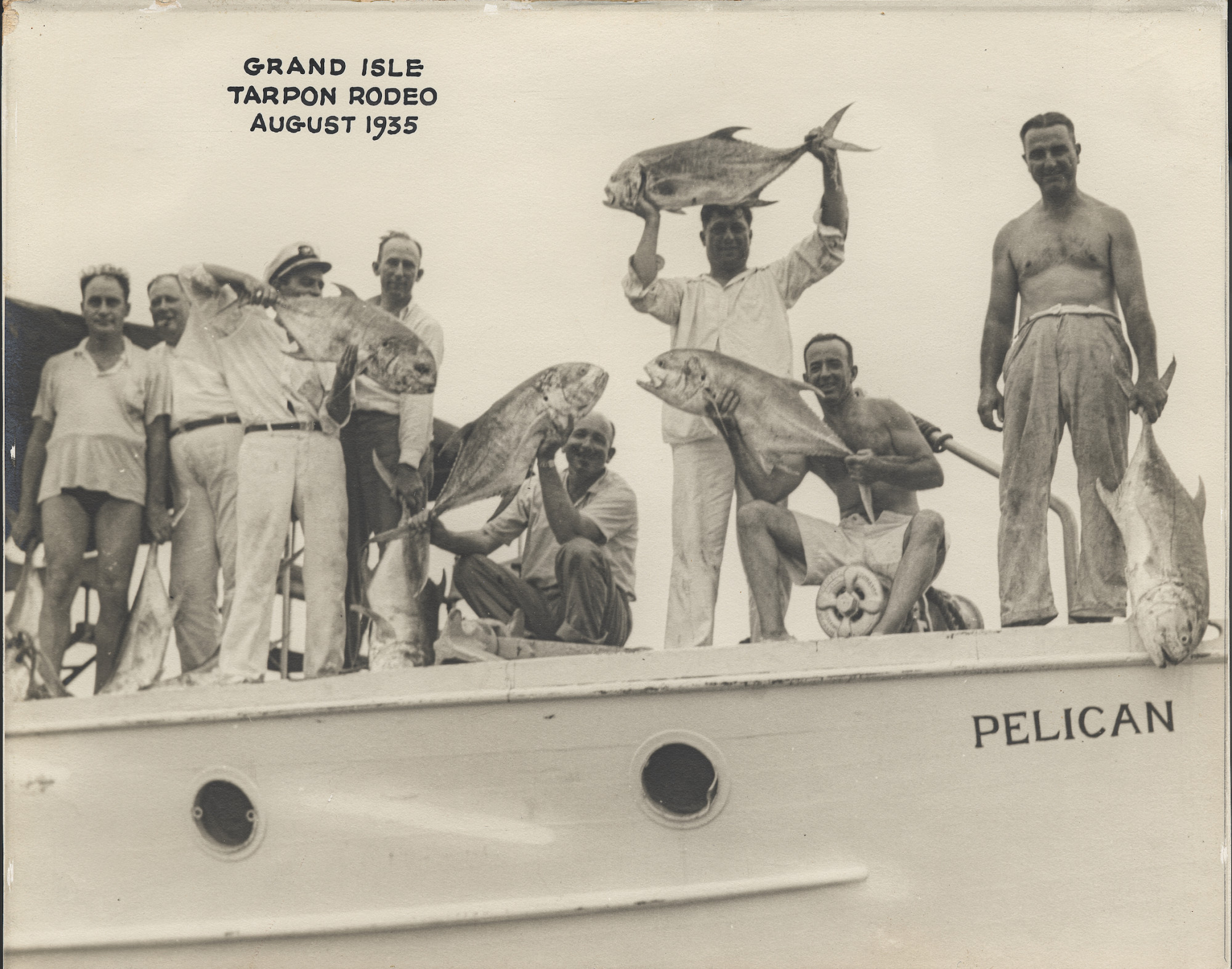

Tarpon Rodeo, Grand Isle, 1935. Photograph courtesy the Louisiana State Museum, Gift of Ms. Roberta Maestri, 1986.103.02.003

Reign of the Silver King

By Christina Leo

All across the island, subjects swear fealty to the king. They ready themselves at dawn. They brandish their hooks. They drink to his health. They wear his name on t-shirts and caps, and show them off in the Starfish Restaurant where his image flashes, airborne, in the paintings on the plastered walls. To stand beside him is the highest of honors—while he swings above the dock, curls above mantels, or gapes beneath blankets of ice. Few will meet him in the wild, but as the sun rises, they seek him out in the ruins of the oil fiefdoms and worship in the hunt through the old pirate bay. They find him dancing there. They pull him up, embrace him, then let him go. And though he goes, the storms still come, churning him far from his island as they will his subjects, who flee instead to the skeletal mainland or else defend lookouts with sandbags and plywood wondering if this rain, this wind, this surge will be the conquest the histories foretold.

Such is the routine of the International Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo, the oldest saltwater fishing tournament in the United States. Not that ninety-six years of existence means much to the contest’s titular “silver king” of sport fish, the swift-swimming, high-jumping behemoth drawing competitors to Louisiana’s barrier islands every last weekend of July since 1928 (or 1932, depending on who you ask). After all, tarpon have been flashing their opalescent scales, watchful eyes, and cavernous mouths long before the hooks of humans dropped into the Gulf of Mexico, owing their record size of eight feet and 280-plus pounds to ancient sharks and mosasaurs chasing them through Cretaceous seas. Their species has seen the shorelines change more times than have the thousand or so permanent residents and thousands more festivalgoers crowding onto Grand Isle’s 7.8 square miles each summer. But the residents and the festivalgoers are not ignorant. They know that change will come again. They know that change is happening now.

The journey to Grand Isle, which is approximately 108 miles south of New Orleans, takes travelers through a network of marshland by way of LA-1, a state highway that also serves as the main roadway through the island. Fog-trailing trucks descend on the island’s turf as if from clouds, tinged by the blue neon light of the Bridge Side Marina’s convenience store windows and cabins for rent. Tilted telephone poles link arms over ditches and driveways slick with mud. Houses rise up on stilts to meet them, quivering under the half-restored wreckage of storm after storm. In pockets of yellow, dune sunflowers clamor for the sky, lining the arteries of side streets and drive-thru daiquiri shacks and the grassy paths to the brown-sand beach.

Once referred to as the “bouquet” of Louisiana’s barrier islands by the nineteenth-century nature writer Martha Field, Grand Isle, then a seven-to-eight-hour steamer ride down the river from New Orleans, made a name for itself as a rare paradise off the coast of a state lacking in the sandy beaches of Texas and Alabama. In the 1920s and beyond, students and faculty of Louisiana State University’s zoology department made regular trips to observe the marine fauna around the island, and had even planned to establish a biological summer camp on its shores (in 2022, the university’s architecture program also got in on the action, with the course “Grand Isle Studio” designed to “address the challenge of architectural permanence in an environment of continual transformation, while encouraging imagination and innovation amongst a dwindling paradise”).

The beachcombers and wranglers ferrying south might once have gazed out from the terraces of lodging like the Oleander Hotel where they slept and ate for $3 a day, or from resorts like the Grand Isle Hotel, reported by the New Orleans Times in 1866 as built to “not only excel in architecture and comfort all the public houses thus far built at Southern watering places, but also to equal, if not surpass, those of Newport, Saratoga, Niagara Falls, etc.” Though efforts persist to restore the bones of those that remain, most visitors now find humbler accommodation at roadside inns or private rentals more hidden from view—but never from view of the sea, which can be seen by looking left or right from many points on the island. And the sea seems to grow closer each year.

Perhaps that’s why, in recent iterations, the rodeo has identified less with its infamous persona of a debaucherous bacchanal. Travel ten years back in time, before Facebook and Instagram turned partying into permanent records, and visitors might bolster themselves for evenings of illicit drugs and even more illicit affairs, shining with sweat to match the slick scales of the fish they sometimes stopped drinking to catch. Now, the rodeo concerns itself less with kegs and more with kids—namely their parents, who have said so long to midnight DJ sessions to notice, instead, that the hour grows late. All walks of life, from inland lawyers to local offshoremen, toast beers at the cornhole yard. Yachts bob peacefully at the docks beside dinghies and pontoons lit by sunsets, and from the long tent where the day’s winning redfish, snapper, catfish, and flounder—as well as any contending tarpon—lie frozen on display, visitors line up as if for a museum exhibit. They stare and they murmur. Under the rodeo pavilion, the announcer on stage signals the start of the crab races—time is of the essence. Wranglers pull up on their boats with their catch, and where once at the weighing station the sight of a beast from the deep drew cheers and guffaws, it now draws the whispered awe of children half the beast’s size, wondering when and if they will ever see such a sight again. Ten-thousand-dollar prize be damned—it’s the marvels of the island they come to see.

Pierre Villere of Mandeville shows off the 123 lbs 13 oz. tarpon he caught at the Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo in July 2007 © The Courier/USA Today Network

Because of this, the Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo has remained something of a Madonna of fishing tournaments, known by loyalists simply as “the Tarpon” and hailed as the Super Bowl of the island’s never-ending spring and summer contests. Amidst a regular stream of environmental disasters, including 2010’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, 2021’s Hurricane Ida, and the subsequent explosion of insurance costs, Grand Isle has nonetheless maintained the event as more than an excuse to take a photo with a fish—it is a cultural institution known throughout the state, a consistent symbol of resilience in the face of loss. It has to be. Due to a swath of natural and human-made problems, whether the physics of coastal erosion or the weight of financial burdens, the Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo—and the unique island that hosts it—endures a present risk of sinking beneath the sea and ending its distinction, perhaps in our own lifetimes.

Whole chains of barrier islands once neighbored these docks. They served as summer retreats for the leisure classes of Louisiana with sand, sun, and shrimping offering luxury and escape from a mainland more famous for bayous than for beaches. Now, only one—Grand Isle—remains habitable, no longer the Gilded Age resort of lore, but a hurricane-battered outcrop playing host to its unexpected superlative.

One might argue that the rodeo is what keeps it habitable. In fact, the festival has remained such a draw to mainlanders that most people who attend the Tarpon Rodeo have no intention of fishing at all.

“I refuse to be a competitor, since that’s not really the environment I enjoy fishing in,” says Todd Cooper, a Baton Rouge native who has attended the rodeo as a spectator for the past several years, and whose in-laws own a vacation home on Grand Isle. Still, he says, the rodeo holds a status akin to Mardi Gras for the island, which has reportedly seen its population expand by the thousands for the span of just a few days.

Cooper’s interpretation checks out with the locals, who claim that the rodeo has drawn upwards of twenty thousand visitors in some years, though that number, like much of the rodeo’s lore, remains debatable. The impact of the population boom for an island indebted to tourism, however, remains an important part of sustainable island life.

Jean Landry, project manager for Grand Isle’s branch of the Nature Conservancy, moved to the island with her family as a teenager, and was not allowed on the street or on the beach during Tarpon Rodeo weekend. “But the Tarpon Rodeo has carried Grand Isle in the summertime. It was always our biggest event. And it helps the businesses, the little mom-and-pop motels, the restaurants, the service stations, the grocery stores. It helps them all to survive the coming winter until the spring comes and the visitors return.”

The daughter of a driller and wireline operator for the oil and gas industry, Landry has spent twenty-five years at the conservancy witnessing the transient lifestyles that drew many people to the island in the first place, whether as Victorian-era shrimpers, contemporary oil harvesters, or stewards of what remains of the island’s natural beauty. And what remains has been enough to draw in some new residents even as more and more leave each year.

For Jimbo Adams, who retired to the island with his wife six years ago, the sands of Grand Isle superseded the more popular, more protected beaches of Gulf Shores, Alabama, where he had lived previously. He even stayed on the island during the brunt of 2021’s Hurricane Ida, hunkering down in the local fire station until he emerged, he says, “into the quietness of nothing.”

“Even so, it’s a fantastic place to live. We’re quiet people, we like the beach. Everyone is welcoming and willing to lend a helping hand, no matter what you need,” he says. “As for the rodeo, it’s what brings people into the grocery stores and the restaurants—that ensures they’ll do well. Long-term growth is another question, though. The island is going to need to find additional resources if they want more people to stay here.” In other words, the more people wandering the streets and beaches during Tarpon weekend, the better. For visitors like Cooper, this means the joyful curiosities of makeshift parades, snow cones from Mayor David Camardelle’s beloved stand Meagan’s, crab-chasing along the beach, and people-watching from the marinas. Even for these humbler escapades, the most popular accommodations on the island must be paid for months to years in advance due to demand.

In some ways, this change of pace harkens back to the childhood of some of the rodeo’s biggest supporters, like 2023’s Tarpon Rodeo president Frank Besson Jr., who grew up on the island.

“You couldn’t do much wrong in those days because it’s only an eight-mile island—my mom and dad would find out pretty quick [if I got into trouble],” he says. “[In the summer], I’d wake up, go find my friends…and we’d go fishing or crabbing. There’s just so much fun growing up as a kid down there.”

P. B. Candies, whose late grandparents Otto and Juanita Candies are pictured on a memorial plaque outside the aforementioned pavilion full of artists, games, and merchandise just beside the Grand Isle Marina weighing station, agrees that the rodeo is evolving.

“It definitely used to be a male-dominated event where guys would get together to spend time away from their wives,” he says, “but now it’s much more family-driven.” In 2022, Cynthia Lee Sheng, president of Jefferson Parish (of which Grand Isle is a part), became the first female Tarpon Rodeo president in history, an honor as part of a family long entrenched in those southern sticks of the state. And at the hour of midnight on the weekend during last year’s festivities, nary a ne’er-do-well could be found; in the light of the Bridge Side Marina, only a few adults, some young children, and a dog remained in the glow, grilling late-night barbecue to the crooning of a boombox.

Whether or not the majority of festivalgoers enjoy the family-friendly change, many remain loyal simply for the leisure of fishing on and around Grand Isle, with families often casting lines for their dinner straight from the beach, or else from the decks of boats ignorant of jet skis or parasailers. For frequent visitors like Jacob “Crawfish Jake” Mouton, a former charter boat captain and full-time crawfish farmer from Lafayette, Louisiana, the charm is enough to keep him coming back.

“It’s so much fun to go out there,” says Mouton, who now captains private boats off Grand Isle for one family of wranglers out of Baton Rouge. “There’s an element of surprise that keeps things interesting, and bringing people to do something that they’ve never done before is always exciting.”

Still, despite attending the rodeo for several years and even hooking a tarpon every now and then, Mouton doesn’t count the silver king among his usual pursuits. Those who do, he says, are in a clique of their own. Maybe because unlike tuna or red snapper, which are among the many edible fish also caught at the rodeo, the tarpon’s reputation rests solely on its status as a trophy fish. The prize for the largest tarpon ever caught in U.S. waters belongs to David Prevost, who in 2015 landed the 246-pound record-holder several miles off the coast of—you guessed it—Grand Isle. But good luck trying to prepare a fish fry with these monsters, or even the smaller members of the family. Sinewy muscles and countless tiny bones mean that their flesh is destined instead for regional research labs or the Second Harvest Food Bank if enough volunteers can be found. Teaming up with the Louisiana branch of the Coastal Conservation Association during the rodeo, the food bank serves the population of Jefferson Parish and still rolls into the island for distributions outside of festival season, proving an especially valuable resource for the estimated thirty percent of Grand Isle residents living below the poverty line. Members of the Grand Isle Tarpon Club have also done their best to avoid waste and promote catch-and-release by teaming up with Louisiana State University and Mississippi State University to study tarpon migration patterns via satellite tracking. Whereas large cash prizes were once doled out only for tarpon weighed at the Grand Isle Marina, now catch-and-release tarpon are just as eligible for reward, incentivizing competitors to leave in the water the fish that still have room to grow. Even so, this meeting between death and progress leans into a fitting metaphor for Grand Isle itself, where organizations like the Coastal Conservation Association and the Nature Conservancy strive to maintain the tarpon’s fragile coastal and marine habitats, which absorb a hurricane’s direct hit at least once every seven or eight years.

That part can’t be helped. Martyrdom is the name of the game for barrier islands, their existence designed to uphold a particular ecosystem of hardy vegetation to slow the force of seaside storms before they reach the mainland.

The same can be said of some animals, too, which in spite of the harsh environment remember and return to the place of their birth to make way for the next generation. In 2015, biologists with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries detected the first loggerhead sea turtle nests to appear on the island in thirty years. In 2022, Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority announced the first evidence of egg-laying by the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle—the world’s smallest and most endangered sea turtle—on the nearby Chandeleur Islands for the first time in seventy-five years.

“We are the only inhabited, live oak–forested island along the coast of the Gulf,” says Landry, whose team has helped preserve one hundred twenty-eight acres of salt marsh and a protected maritime forest of fifty-six acres. “[The island also sits] almost dead center of the Mississippi flyway for the migration of songbirds in the springtime and fall.” In 2023, Landry also helped facilitate the island’s twenty-fifth Migratory Bird Festival, which has been known to welcome hundreds of visitors from as far away as Washington State. Grand Isle, she says, represents an important ecological stronghold of maritime forest and marsh that the conservancy has protected and restored for decades.

Grand Isle mayor David Camardelle, who has held the post since 1997, has also spearheaded multiple efforts to slow the rate of destruction through a continued push for government grants and stone jetties. In spite of the island’s unique “burrito levee,” the thirteen-foot-tall tube of sand lying along the shores, Grand Isle still suffers from the state’s accelerated rate of land loss—an area any Louisiana schoolchild has been taught is the equivalent of one football field every one hundred minutes.

“If we don’t protect Grand Isle, I predict that the next big storm will have Bourbon Street under eight to ten feet of water,” says Camardelle. “I want people to understand that I’m not begging all the time; I just want to do it right and let Mother Nature heal itself.”

Unfortunately, Mother Nature is much swifter at tearing down her accomplishments than she is at growing them. Landry’s beloved forest growing on the sandy beach ridges—a unique habitat referred to as a chenier, named for the French word chêne, or oak—once pulled the island’s soils together and protected songbirds and other wildlife from high winds. But now many of their relatives stand bare and leafless, not nearly the all-encompassing environment that gave way for the development of human habitation.

But if humans can take things away, maybe they can bring them back. Regardless of the inevitable struggles that come with living at the mouth of an ever-hungry, ever-warming sea, people keep coming back to Grand Isle generation after generation, which means that building projects extend beyond a mere stabilizing of the coast—all those people traveling down for the rodeo need a place to stay, after all.

The current iteration of the island’s resort culture little resembles its black-and-white, archival photographs of wide plantation-style porches, sparkling gas lamps, and linen-draped promenades. Instead, visitors more often stay in comely single-family rentals, or else in cabins like the aforementioned Bridge Side Marina. As for the permanent residents, many of them reside in what the locals refer to as “camps,” or the stilted homes rising high above the line of anticipated floods. Even more continue to reside in a neighborhood of FEMA trailers supplied by the government after Hurricane Ida, their rows parked near the dune grasses around the bend from the beach. No formalwear needed; nearly every diner in the island’s handful of fry-laden restaurants can be found lounging in the comfort of t-shirts advertising one fishing competition or another, if not the purple and gold of the LSU Tigers.

Toward the center of the island sits what might be considered the most luxurious of the resort-style accommodations—the Hurricane Hole, a multi-unit, Caribbean-inspired resort named for natural inlets where boats can be docked to find protection from incoming storms. An on-site restaurant serves higher-end dishes and drinks, while an attached bar hosts live music and a scenic view of the condos, luxury pool, gym, and marina. A short walk away along the docks sits another bar where twenty- and thirty-somethings gather for music, cornhole, and daiquiris.

Watching the well-dressed, coiffed, and made-up guests walking around the docks, diners from the upstairs restaurant might look down and wonder where on the island such gussying up would be necessary—only to see them disappear into the polished wood cabins of glistening white yachts, ready to watch the troubles of the landlubbers disappear behind them.

It’s easy to understand why someone would rather come and go than remain stuck on land here. Because of a combination of development and inevitability of natural disaster, Grand Isle risks the same devastation suffered by what was once one of the largest and most impressive of Louisiana’s barrier islands, Last Island, which was split in two and destroyed by a hurricane in 1856. The disaster, which killed hundreds of vacationers, inspired the New Orleans travel writer Lafcadio Hearn’s 1889 novella, Chita: A Memory of Last Island, one of several texts to depict Grand Isle as what the writer once referred to as “the prettiest island of the Gulf.”

But the most famous representation of Grand Isle’s heyday almost certainly belongs to the writer Kate Chopin, whose pre-Modernist, proto-feminist portrayals of class, race, and naturalism appear on many a high school syllabus and would pave the way for the likes of Hemingway, Faulkner, and O’Connor. In Chopin’s 1899 novel The Awakening—itself theorized to be a response to the island’s devastation caused by 1893’s Chenière Caminada hurricane, the deadliest in Louisiana history—the despondent New Orleans socialite Edna Pontellier finds her domestic life challenged during a holiday on Grand Isle. Chopin’s island is a place depicted in all its “slipperiness,” in the words of scholar Jessica Bridget George.

“By revealing how a storm or a flood can create and then douse an entire world in a matter of minutes,” George writes in the Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, “Chopin materializes places which otherwise appear as fantasy—places which exist only temporarily in the perpetually changing landscapes of the Louisiana coastline.” It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that the surrounding waters of Barataria Bay take their name from the imaginary kingdom bequeathed to the foolhardy Sancho Panza in Don Quixote.

The lure of the island’s transient nature expands beyond the written page, too. Famed photographer Fonville Winans documented the people and places of Grand Isle in the 1930s, and even Nicolas Cage starred in a campy thriller, Grand Isle, in 2019, hanging loosely onto the island’s mythic status as a hotspot for scruffy vagabonds with a vengeance. And why not? One of the most enduring legends surrounding the island and its neighboring waters revolves around the famed pirate Jean Lafitte, who, rumor has it, buried treasure in the sandy soil of the barrier islands.

Whatever treasure may have been buried, though, it almost certainly no longer exists. Louisiana’s barrier islands have fallen on the sword of storms countless times, losing land and everything that stands on it in the process. The most recent deluge came from Hurricane Ida in 2021, a Category 4 storm whose one-hundred-fifty-mile-per-hour winds and up to fourteen-foot storm surges obliterated or damaged nearly every building on the island and left residents without power for four months. Ida ties with 2020’s Hurricane Laura and 1856’s Last Island Hurricane as the strongest to have ever hit the state.

“I was probably one of the last people who had communication with the mayor on the island when Ida hit,” says Cynthia Lee Sheng, president of Jefferson Parish, which contains Grand Isle. “The mayor would have to go to the bridge to try and get reception to me. Eventually we lost radio contact. All we had were screens of video footage, watching the weather rolling in and feeling so vulnerable and helpless.”

After the storm dissipated, Sheng finally set foot on the island to observe the wreckage.

“It looked like a bomb went off,” she says. “There was no color—just a white-gray. You couldn’t even see the extent of the destruction because there was no evidence of it; it was just gone.”

Unfortunately, Mother Nature is much swifter at tearing down her accomplishments than she is at growing them.

Two years afterward, at the time of the writing of this story, visitors to the Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo still faced an apocalyptic scene. Every other structure down the main Highway 1 withdrew behind shallow, muddy ditches, reduced to rubble. Across the street from the yellow plaster of the Starfish Restaurant sat a series of broken poles and a slanted foundation strewn with wreckage. Down the side streets named for flowering trees and fruits—as well as sentimental addresses like “Memory Lane”—carpenters clambered on surviving rooftops in the heat. On the beaches of Grand Isle State Park, whose wet, silty shores were once believed to cure various ailments, the remains of Camardelle’s stone jetties stared boldly out to sea. In the near distance, the severed ruins of the nine-hundred-foot boardwalk languished like the discarded plaything of an absent giant, unreachable and impassable by the few families wading in the near-waveless surf or splashing in the tide pools beneath the occasional circling of a pelican. Back inland, Hurricane Hole gleamed only because it was among the first to recover from millions of dollars of damage caused by the storm. It looks brand new because it basically is.

The result is a generally battered appearance from the west to the east ends of the island, but the aftermath did more than upset the aesthetics of the place. It upset the finances.

These days, most of the new constructions—and there are many—belong to wealthy mainlanders who can afford to rebuild without the grants Jefferson Parish desperately needs, with many native residents (who can no longer reap a living from the sea as their ancestors could) forced to live in government-acquired trailers at the state park. Standing outside the quiet parking lot of the Bridge Side Marina on Highway 1, looking left to right across a strip of land so narrow you can see the ocean on either side, one can’t help but wonder: Why stay at all?

“The insurance people might use the word ‘stupidity,’” laughs the captain Mouton, “but I’d use the word ‘resiliency.’ The resiliency is unmatched. If you like Grand Isle, you probably love Grand Isle.”

The subjects understand; to live under the reign of the silver king, one must be prepared to pay tribute. And while those tidal tithes may one day fail to save the last sentries of Grand Isle’s dwindling kingdom, for now, the sea continues to send its ambassadors; the ancestral nesting grounds have not been forgotten, and the shining giants know better than anyone how to prepare for the leap from obscurity to emergence and back again. Any angler will tell you: When the tarpon jumps, the rod must bow down.

“We love this place,” says Mayor Camardelle, preparing for yet another meeting to determine the island’s next move. “As I always say: As long as there’s one grain of sand where we can plant the American flag, we’re not going anywhere.”

This essay was published with support from The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.