Suffering Embarrassments in a Small Town

By DW McKinney

No Longer Peter Cohen’s Property #5, 2020, archival inkjet print, by Alayna N. Pernell from the series Our Mothers’ Gardens © The artist

Halfway through my artist residency in Paonia, Colorado, I am struck with the fleeting sense that it’s already over and I have accomplished nothing. I haven’t finished outlining my travel essay collection, my proposed project for the residency. I haven’t visited the Bross Hotel, the town’s famed historic bed-and-breakfast, to ask questions about how the hotel accommodated Black travelers during Jim Crow segregation. I haven’t been to the town’s museums to do similar research—they’re never open during the listed operating hours. The weight of these tasks burdens me as I walk to the espresso café.

The sun casts me in sharp relief against the dusty road behind the residency’s studio. Being a Black artist-in-residence in this small Colorado town means that almost everyone pegs me as a visitor. Most people deduce where I’m staying in town without me having to open my mouth. At our first greeting, the florist; two different grocers; the clerks at the organic food shop; and random customers at bakeries, thrift shops, and wherever else I occupy space want to know: “What brings you here?” A cashier blurted, “You don’t live here,” then stumbled over her correction: “Do you live here? I haven’t seen you before.” Others confuse me for another Black woman, a doppelgänger who they’ve spotted at the gas station, the community theater, or other places they’re sure they’ve seen me despite my protests. I am often reminded of my displacement.

The café is the only place in town that feels genuinely welcoming. The small building sits on a street corner and shares its indoor space with a bicycle repair shop. Morgan, the café owner, bustles behind the counter when I arrive, and his vibrant energy permeates the room. His charm is undeniable as he balances filling orders and engaging in conversation with customers, all while offering lightning-quick smiles to everyone who walks in. When it’s my turn, Morgan asks about my writing project—casually, as if we’ve never stopped talking since my last visit. His question is a delightful change of pace from my conversations with everyone else. Morgan and I have only ever chatted about our mutual appreciation for comics and graphic novels. He pauses to take an order from a blond woman. She disappears into the neighboring bike repair shop while the coffee brews, and Morgan signals for me to continue.

“My project’s about travel and Black identity,” I explain, “while also combining aspects of the Green Book. Have you heard of it before?” Morgan hasn’t, and as he asks me to tell him more, a tall sun-worn man with a trucker hat announces himself in the doorway. The man cradles a rooster in his arms; the glossy feathers on its breast are black and green. I’M OK is inked in black on the man’s left forearm. Morgan and I gape at the man and the rooster.

“He’s my friend,” Rooster Man says. “He helps me with my anxiety.” Rooster Man states that he’s “never been here before,” as if he’s just been beamed down to earth a few minutes ago. I scrutinize his wide belt buckle and dusty work boots, the way chaotic energy ripples through his lean, muscled body as he paces in front of the register. Dread pools along my spine, and I scoot away until the window counter digs into my back. Rooster Man reminds me of someone dangerous from my past. The blond woman appears from the bike shop, and Rooster Man mutters in her ear about his coffee order. There’s a disagreement about whether he wanted it hot or cold before he resigns himself to a hot drink—“I’ll come back another time for a cold one!”—then leaves with his rooster. The woman trails behind him with their coffees.

“So, the Green Book,” Morgan says.

“Yes, the Green Book was created for Black travelers to know which places were safe to visit in the U.S. during Jim Crow.” The idea of the Green Book stuns Morgan, but he recognizes its use, especially in the context of this small town that is, he admits with a nod and sweep of his arms, “very white and not very diverse.” It’s a relief to hear someone acknowledge Paonia’s homogeneity full stop. He does so without also emphatically adding, “But racism doesn’t exist here,” as other locals had said to me. Or as a bookstore clerk clarified when pressed, “But we have diversity of thought.”

A breeze curls overhead as I settle into my project at a table outside, near the fence that runs along the town’s irrigation canal. I am farthest away from everyone, but with the canal behind me and trees blocking access to the adjacent road, there’s only one way in and out of this patio section. Crowing disrupts the quiet. I turn to see the rooster pecking the ground. The blond woman from earlier makes eye contact with me from across the patio where she sits alone on a bench; Rooster Man is nowhere in sight. She and I laugh over the absurd interruption. I turn to my laptop. The rooster crows. My thoughts stutter. The rooster crows again. Expletives swarm my mind.

“Jesus fucking Christ!” shouts Rooster Man. His sudden appearance startles me, and I offer a cursory nod and close-lipped smile in his direction that I immediately regret. “Hey, can I talk to you?” he asks. I try to ignore him as the gravel crunching underfoot sounds his approach. “Can I talk to you?”

I don’t want to talk to him. The dread along my spine has now stretched across my back. I don’t know what to say. I’m worried that our interaction will become a tidbit of gossip to pass around town. And as a woman who’s rejected men’s advances and received verbal abuse in response, I don’t want to invite violence into this situation. But Rooster Man is already reaching out to grab the chair next to me when I mumble a shaky “yes.”

Victor Hugo Green published The Negro Motorist Green Book travel guide in 1936. It was the first of what became an annual publication. Green, a postal worker, mapped out locations in New York City that were safe for Black motorists, which made up the first edition of the guide before high demand for the book led to the inclusion of additional states and international destinations in later editions. With time, the guide—colloquially known as the Green Book—provided easier navigation for Black Americans traversing the racially segregated South and hidden sundown towns. In the 1949 facsimile edition that I own, the introduction mentions that the book allows Black motorists to travel “without embarrassment.” Embarrassment was, of course, a euphemism for worse ills to suffer during a time when segregation was violently enforced. With this guide, Black travelers reduced the possibility of suffering lynchings, facing harassment, and encountering the Ku Klux Klan and its harbingers of death.

Hollywood sank its talons into the publication with the 2018 film Green Book, directed by Peter Farrelly. In the movie, Mahershala Ali portrays Black musician Don Shirley, who hires Italian American Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga (played by Viggo Mortensen) to be his driver through the American South in 1962. Deterred by critical reviews asserting that Green Book centered Vallelonga over Shirley despite being inspired by a book about Black survival, I chose not to watch the film. I instead turned to my maternal grandparents for their experiences using the Green Book.

My grandparents are from Alabama and Louisiana. They had been living in Kentucky when they moved to California with my mother, then two years old, in the same year Shirley was traveling with Vallelonga. Too late to ask my grandfather—the more reliable historian in our family before his passing—I ask my grandmother about their travels through the South.

The first time I call my grandmother about it, she pretends not to understand what I’m asking her, or to know about the Green Book. I wait a few weeks then ask again. This time my grandmother acknowledges the book’s existence but tersely claims that she and my grandfather never used it. It’s possible. Not every Black person used the Green Book, but it’s the dismissive way she responds that strikes me as false, as if I’ve broken some taboo by suggesting a need for the book at all. Her explanation is also noticeably absent of the reality of racial segregation during that time.

“We didn’t even think about it,” my grandmother says. “It” is the racism she refuses to address. According to her, they lived a life without the Green Book’s foretold “embarrassments.” In fact, when I rummage through the archives of my memory, I can’t recall my grandmother ever mentioning how racism hounded her day-to-day life. Maybe it did, but the experiences didn’t taint her with the type of shame that so many of us can’t shake, and so it never seemed worth mentioning. It’s a type of charmed life that I can’t fathom.

I don’t remember the first time I asked the internet if I was safe in a city that was not my hometown. Yet the question became so frequent and so regular that I didn’t think twice when I typed, “Are Black people safe in ___?” or “What are race relations like in ___?” Travel forums unfolded years-long discussions about culture shock and discrimination. Blog posts and articles detailed the existence of Black expat communities abroad. In this way my travel guidebook was the historical compendium of life between Black folks and everyone else. I referred to this record often, whether the place was an unfamiliar U.S. city I was visiting for an overnight trip or a potential study abroad destination. For weeks ahead of traveling, I would spend dozens of hours researching racist incidents at my destination until I compiled a dense history of irrefutable racism. To my obsessive mind, it was proof that what I read would happen to me, in some form, and I had to be prepared for it.

At the start of the residency in Paonia, Colorado, it had been two years since I had asked the digital-verse, “Does anti-Black racism exist in ___?” I don’t realize that I’ve abandoned this habit of excavating the possibilities of danger until one of the residency’s board members is driving me from the Grand Junction Regional Airport to the studio. I ask him how people in town might react to challenging ideas. I wonder to myself how I might be received, how my safety might be jeopardized, while I researched the history of Paonia’s Black citizenry. “Well, people are pretty good about it,” he begins, “but it is a small town so we try not to step on too many toes.”

I’m still trying to figure out how to ask the necessary questions for my project without upsetting the townspeople and their delicate toes when we finally arrive at the studio. It’s a century-old building that once supplied the town’s electricity. After a tour, I ask for keys to lock the front door while I’m away.

“There are fifteen hundred people in this town,” the board member says. “Most leave their doors unlocked. Crime’s not really an issue here.” The implication is that I too should be okay leaving the door unlocked. I too should be okay adopting the town’s implicit rules regarding community responsibility. Yet I’m the only one remembering that there are other rules that only apply to Black people like me, and they most often revolve around others’ perceptions of safety. Still, I ask for the keys. I’m given a set that I have to share with the other residents.

Being asked to adopt a standard that cedes my needs to those of the majority exemplifies the kind of curated comfort the town prides itself on. “It’s not like anywhere you’ve ever been,” a local remarks. Others describe it as “wonderful,” “utopian,” and “special.” It is the smallest town I have ever lived in (even if temporarily), but it is like so many other places in this country: The obvious erasure of Blackness is heavy-handed.

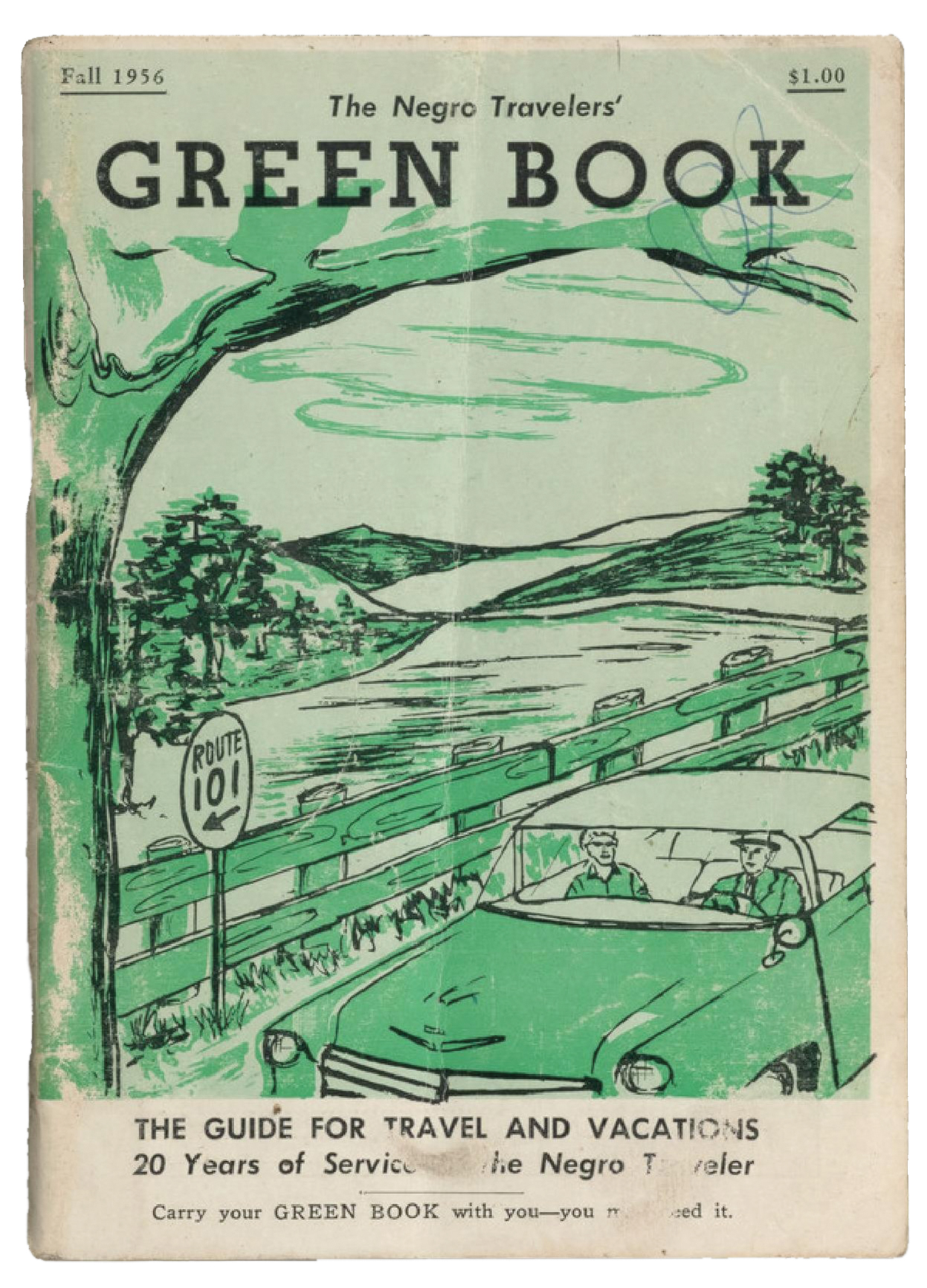

The Negro Travelers’ Green Book: The Guide for Travel & Vacations, Fall 1956 edition. Publisher: Victor H. Green & Co. Courtesy New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

“God you’re so damn beautiful,” Rooster Man says. He compliments my skin as his eyes trace the length of my body. Rooster Man says he loves my hair, the same black-and-silver braids that a woman at the farm supply store called “dreads” before asking if I ordered them online. He catalogs everything that he loves about my body. In his exuberant fetishization, I sip my chai. I’m too emotionally exhausted to do anything but accept what’s happening.

“I could use more color in my life,” Rooster Man says. “I mean seriously. I’ve lived here all my life, and there are just no people like you here.” As he stares and leans forward, I sense that he wants something from me, for me to do something. I look to a brunette woman at the table nearest us for help. We’re directly in her line of sight. She does nothing except tilt her eyes downward at her laptop screen.

“We could all use more color here, you know,” Rooster Man says. “Like I know a Black guy.” I ask Rooster Man where this guy works even though I’m sure I already know the answer. While conducting research at the town’s library the week before, I met its lone Black librarian. She whispered how excited she was to see “another one of us,” even if it was for a short visit. The librarian then enumerated the eleven Black people who she knew lived in town, including “the little girl being raised by Mennonites.”

“He’s at the hardware store,” Rooster Man says. “He keeps a knife on him. That’s fucked up. I don’t—I don’t want anything to happen to you here. I’ll kill anyone who tries to hurt you. I’ll kill everyone! Just tell me if someone tries to hurt you, and I’ll kill them.”

I nod. I empathize with this Black guy I’ve never met. A box cutter costs $6.99 at the local market. I priced it on my second day in town after a Colombian friend asked if I had packed any weapons to protect myself. I wish I had bought it. Soon Rooster Man heads toward the café so I can finish working. Minutes later, the rooster crows and as if on cue, he returns.

“Hey, can I show you a song I just made?” Rooster Man asks. Now that he’s turned at a different angle, I read I’M SAFE inked on his right forearm. What about me? Rooster Man wanders off to take a phone call and the bird crows again. Maybe it’s been warning me this entire time. I uncoil my body, shove my belongings into my backpack, and flee—taking a meandering route to the artist studio in case Rooster Man decides to follow me.

Lehna, the other Black artist-in-residence, is in the kitchen making breakfast for her daughter when I return. I tell Lehna what happened. “That’s so racist,” she says. She’s furious and devastated. Lehna’s apologies affirm me, but she shouldn’t be the one saying them. We unfold ourselves a little in the kitchen, discussing the discomfort we feel in town. The way vulnerability is raw against our skin when we walk around alone. How a car slowing down beside us unsettles us to the bone. The quiet, scenic paths we take to the river to feel safe. The places where we no longer want to eat because there are too many people staring, watching. But we have to keep moving forward. We’re allowed to exist in this utopia just as much as anyone else.

Every time I apply to a writing residency, I think about Jill Louise Busby’s essay “Writing Black Essays in White People’s Houses.” It’s not the Green Book, but in criticizing the writing residency industrial complex, Busby issues her own kind of warning about temporarily residing in historically white spaces for financially supported creative productivity. In the essay, Busby writes about the implied expectations placed on Black artists from those who endow them with the residencies, most often white people. A performance of gratitude surrounds the artists as they are in these spaces “doing the black arts,” and they are expected to do them in a way that assuages the egos of their white benefactors.

Residencies are a space for creative freedom, and yet there is this baggage looming in the background. When I read Busby’s essay, I had just returned from attending my first two writing residencies, two months apart. Both were in isolated places where I negotiated the safety of my presence with trying to complete the work I had been invited to do. Busby writes, “As it grows dark outside, the ocean view becomes implied, and we become less implied. We are reflected back to ourselves in the glass under the dim light of a low-hanging fixture, more easily seen by the neighbors…” And in her words I saw myself sitting at my desk in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, the woods disappearing into the evening and the lamplight illuminating me for those passing by on the sidewalk below. “The black artists are here doing the black arts, remember?”

If others had forgotten, I hadn’t. Beyond writing Black essays in white people’s houses, we are also doing so in white people’s towns. I prefaced both of those first residencies with exhaustive searches for news articles related to hate crimes and racial discrimination in the areas surrounding my destination—and the residency institutions themselves. I emailed previous writers of color about their experiences, their perception of safety, and their (dis)comfort—all while I packed my luggage and followed in their footsteps, hoping for a better outcome.

I visit the café the day after the encounter with Rooster Man because I want to reclaim that space. The town gossip does its job and people slowly discover what happened. In turn, I learn Rooster Man’s real name. I learn that he is a dutiful husband and father, and that his wife just gave birth to their second child. When Morgan’s not working, a barista at the café mentions that Rooster Man is the brother of one of her friends. He is vouched for, and all of this proffered information creates a portrait of an upstanding citizen that excuses his behavior.

“That’s not who he is,” the barista says. He’s allegedly having a mental health crisis. “Not to diminish what you experienced. He’s just making everyone uncomfortable right now.” I wonder if everyone else is checking over their shoulders or altering their daily routine. The barista’s words sow doubt in the back of my mind, and I begin invalidating my own experiences. I vacillate between talking about what happened to avoiding all mention of it. But if the people who came before me stopped talking, if they let their experiences become erased, there would be no Green Book. There would be no markers to guide us along the invisible trailways toward our communal safety.

The weight of my experience never leaves. I push it off me every morning when I wake up. I drag it down the quaint streets while I shop for groceries and attempt several more visits to the museums that are never open. I try to wash it away in the swirling waters of the North Fork Gunnison River. Yet it’s still there when I drop mail off at the post office and finally see the woman who I suspect is my doppelgänger, though our only similarity is that we are Black women wearing box braids. I catch her eye and smile, but she only glances at me before turning around. I think of Busby, who wrote, “If I lived in this town, I would have no special occasion or collective camouflage to save me. There would be no other black person to pay the price for my compromise. No black person who could’ve easily been me instead. I would be immediately identifiable, the only one mistaking myself for someone else.” The only one suffering under the unimaginable burden of accumulated embarrassments.

I decide that I am unwilling to suffer in anyone’s utopia. If only for a moment, I want to pull back the veil and expose a harsher truth that some people are unwilling to face. The other artists and I are required to host a public exhibition at the end of the residency to present our art to the community. One artist sets up a table by the entrance with several ceramic pieces that symbolize life, childbirth, and death alongside a bouquet of flowers—a memorialization of grief and the artist’s recently deceased mother. Lehna adorns an alcove with neon-colored paintings, a fabric tapestry, and ancestral photographs decorated with bright ribbons and beaded strings. The third resident presents a rock installation and above it hangs small landscape paintings in honor of Colorado’s Ute Indigenous tribe, with which she shares ancestry.

A public reading would be expected of me as a writer, but in lieu of one, I take a line from one of my essays and project it in bold black letters against one of the studio’s white walls. It reads: “THEY DID NOT KILL ME HERE…” I accompany the projection with two captions representing a hypothetical conversation between attendees and me. The first caption reads:

I answer: I’m reflecting on an excerpt from my essay “I’ll Be Seeing You: A Black Woman Travels in 2017,” published with Hippocampus Magazine in 2020. This sentence came to me, again, in the wake of a racist encounter on July 18, 2023, in Paonia, CO.”

I answer: Toni Morrison once said, “The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being” (1975, Portland State lecture).

My projection is squeezed in between the ceramic vases and a large photograph of a Black woman’s smiling mouth. Low chatter fills the room as people shuffle between the installations. Many attendees are grim-faced while they read my words, stark against the blank wall. I receive a few apologies. One woman still asks, “What happened?” then awkwardly walks away when I smile and refuse to answer. Mostly I take pleasure in subverting this particular embarrassment in front of everyone. It is theirs to carry. But whether anyone else cares or not, it’s also a public proclamation that I am still living, still thriving, still traveling through this world.