Maati Jone Primm, owner of Marshall’s Music and Bookstore, Farish Street, Jackson, MS © Timothy Ivy

A Walk With Ancestors

Inside a pre-integration, Black Belt, Black-owned bookstore

By Adria R. Walker

When I walked into Marshall’s Music and Bookstore in my hometown of Jackson, Mississippi, for the first time as an adult, I recovered a warmth I hadn’t even realized I’d lost. It was 2020 and, in a few weeks, I would be moving out of Mississippi for a newspaper reporting job in western New York. I wanted to get a copy of Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells as I trekked out of the Magnolia State—the same trek my idol Wells had made over a century before me. Though I hadn’t been to the bookstore in years, I called Marshall’s before calling any other local shop—the charming, independently owned Lemuria Books or the Book Rack, a favorite used bookstore of mine—to see if they could order the book. Better than having to order it, Maati Jone Primm, Marshall’s owner, had the book in stock. I drove to the bookstore the next morning, shortly after it opened, to purchase my copy.

Walking in, I was touched by two things. Firstly, I was moved by the familiarity of the store, though I couldn’t remember the last time I had visited. Secondly, I felt the comfort of the elders and ancestors in photos lining the walls of the shop. Ida, yes, but others too. So many Mississippians, from Annie Devine to Henry T. Sampson, so many Jacksonians, Charles Tisdale and Margaret Walker Alexander, among them. The store is small, the center row extending from front to back. On either side, books are stacked three rows deep on tables that stretch back several feet, but the space feels cozy instead of cramped.

Like familial ancestors who have long since passed, images of Black leaders and guides covered the room’s white walls, forming a phalanx of support. Printouts, some black and white, some color, were centered on sheets of white copier paper, each bearing a hand-lettered caption describing the figure pictured. In between the images, a sign spelled out YOUR HOPE HEADQUARTERS.

Images from the civil rights movement and historical images of Farish Street, the once renowned segregation-era Black economic hub and the street where the bookstore is still located, line the center wall. Hannibal of Carthage gazes out between Aaron Henry and Frederick Douglass. Ann Moody is to the right of the University of Timbuktu. To the far right are Alexandre Dumas, Nina Simone, Marcus Garvey, Mansa Musa, and Bo Diddley.

A different Black-owned bookstore regularly claims the title of oldest Black-owned bookstore, but it did not originate in the Black Belt, in a segregated, Jim Crow–era Black mecca. Marshall’s predates it by decades. And as independent, brick-and-mortar bookstores across the country—Black-owned and otherwise—are struggling to survive, Marshall’s near-century of existence is all the more remarkable.

Having opened in 1938, Marshall’s is most likely the oldest continuously operating Black-owned bookstore in America. The bookstore primarily focuses on Black history and culture. Copies of We Will Shoot Back, Death of Innocence, and Jubilee line shelves. The children’s section is just as rich; I Never Had It Made, Jackie Robinson’s autobiography; Brown girl, Brown boy, What could you be?; and Alphabet of Black Cultures beckon young readers. Churches and parishioners are some of Marshall’s longest-standing customers and one of the biggest reasons the store has been able to weather the changed fortunes of the surrounding district, so there are ample copies of Bibles, hymnals, and church supplies. The surplus of sacred texts is such that Marshall’s is often described as a Christian bookstore, rightfully, Primm said, fueled by a base that has sustained the small but mighty store as Amazon and big-box bookstores have pulled customers away. Marshall’s is a key character in the history of Jackson and the state and region at large—proof of the importance of community relationships and support.

Jackson, Mississippi, is the Blackest city in America, with Black people making up over eighty percent of the population. The city, which celebrated its bicentennial in 2022, has long been a hotbed of Black activism and culture. Consistently a small city as compared to other Southern capitals, Jackson has produced literary giants like Mildred D. Taylor, Richard Wright, Margaret Walker Alexander, and Kiese Laymon.

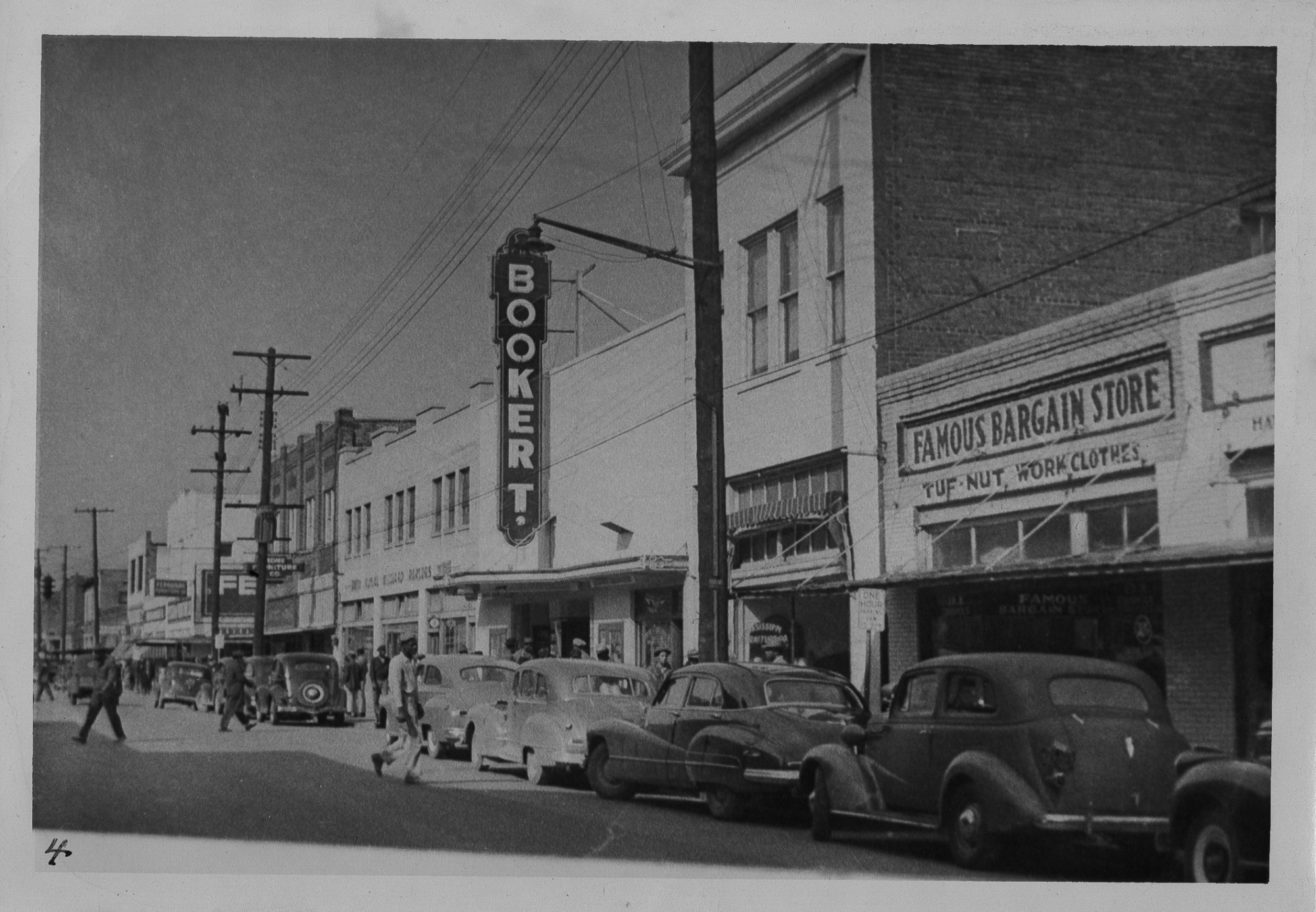

Farish Street, 1947, a photograph by Charles C. Mosely, Jr. Courtesy the August Meier Farish Street Photograph Collection, Margaret Walker Center, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS

Prior to integration, Jackson’s Farish Street, a 125-acre district, was a bustling hub of Black economic and cultural wealth. The street from which the district gets its name was full of flourishing shops, nightclubs, and theaters. At least two record labels and theaters called Farish Street home, including Trumpet Records and the Alamo, while Jackson State University was located there for a year before moving about a mile and a half away to its current location west of downtown. In its heyday, Farish Street was the largest economically independent African American community in the state. It was still remembered fondly decades later, when I was a little girl. Elders in the beauty shop where I got my hair done as a child regularly conjured up vivid images and memories of it, doing so in such a way that I understood the magnitude of what was lost as Farish Street declined.

This is the district in which Medgar Evers had his insurance office—still visible at 507 N. Farish—and operated the NAACP’s first field office, until it moved to nearby Lynch Street in 1955. It is where, during Jim Crow, Black people could exist with dignity and respect, where, in the early 1910s, Black people had access to almost a dozen Black attorneys, four doctors, three dentists, two jewelers, two loan companies, and a bank, along with two hospitals and a plethora of retailers.

And it is the street on which Louis Wilcher, then pastor of Greater Pearlie Grove Missionary Baptist Church, opened the store that was then known as Wilcher’s Music and Bookstore.

Customers who visit today, many of whom have not learned about these figures or sites before, feel a deep sense of pride when they look at the Black history wall, Marshall’s owner Primm said. They come in and take pictures or bring their children and grandchildren with them to see it.

The wall started years ago as a Black History Month display. At the end of February, Primm asked her customers if she should take it down. “They were like no,” she said with a laugh. “Some of them looked at me like, ‘I’ll get a switch if you do. I’ll spank them legs if you touch that wall.’”

In the years since, Primm has touched the wall several times. But instead of removing images, she continues to add to it.

Sixteen years ago, Primm would not have imagined how firmly planted she would be in Mississippi. She was content working for corporate America while living in Chicago. Her mother, Louise Marshall, was at the time the owner of Marshall’s Music and Bookstore. She did not see herself living elsewhere, though she knew of her connection to Mississippi.

During the Great Migration, approximately six million Black Americans left the South, many ending up in what would become the Rust Belt. Hundreds of thousands of Black Mississippians, traveling on the Illinois Central Railroad or via car on I-55, ended up in Chicago. Like a southern live oak, whose branches sprawl in complicated and dizzying ways, those migrant Mississippians left tracks across the country.

Nearly two decades ago, Primm’s family’s branches called her home, from Chicago to Mississippi. Answering that call, she became the fifth-generation owner of Marshall’s Music and Bookstore.

From the beginning, members of Primm’s family worked at the store. When Wilcher decided to retire, he sold the bookstore to Ora Page Marshall, Primm’s grandmother, who had worked as a bookseller at the store. Ora Marshall was a force of a woman whose legacy lives today. On one of the walls there is a photo of the 1908 graduating class of Utica Technical Institute, now part of Hinds Community College. Ora Marshall is third from the left. Her steady, proud gaze greets all who enter the store. She had six daughters, two of whom also worked in the business of bookselling.

When she was prepared to retire, Marshall sold the bookstore to her daughter, Beatrice Walton. Walton owned the bookstore for thirty-seven years before selling it to her sister, Louise Marshall, Primm’s mother. Louise had marched with Martin Luther King Jr. at the original March on Washington in 1963. Primm remembers with a laugh that she “had an attitude” because her mother was out marching and not with her.

“We were born to protest and be intolerant of injustice. We were never supposed to accept that, and that’s the way I was taught,” Primm said.

Louise Marshall owned the bookstore for eight years before selling it to her daughter, Primm, who has owned it for sixteen. “That continuity is really, really important, regardless of who you are,” she said. “That’s what makes everything functional and how you can elevate.”

And yet, despite that continuity and despite the store’s legacy, it is largely ignored and erased outside of the city of Jackson and outside of the state of Mississippi. Every few months, specifically in February or on Juneteenth, lists of Black-owned bookstores go viral. Multiple publications feature lists in each city and state, but there is one name that is often conspicuously missing: Marshall’s Music and Bookstore. Googling “oldest Black bookstore in America” may not lead you to Marshall’s, and even Wikipedia fails to acknowledge Marshall’s existence.

Primm doesn’t necessarily think the exclusion is intentional. The 1960s brought a naming tradition in which Black cultural stores or businesses specifically and intentionally referenced Black historical figures. Even now, Black-owned bookstores regularly reference Black culture, history, and authors in their names. For example, Raleigh, North Carolina, is home to Liberation Station Bookstore, while Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is home to Hakim’s Bookshop, that city’s oldest Black-owned bookstore. But Marshall’s predates that naming tradition by a couple of decades. “When you look for Black bookstores…typically there’s something about the name that would suggest that it’s Black, which ours doesn’t,” Primm said. “The only thing is our address.”

As people across the country continue to crave representation and an acknowledgement of Black history in the face of efforts to suppress it, recognizing Marshall’s history, its longevity, and its role in such an important Black city becomes all the more necessary.

“Marshall’s was there in the height, in the heyday, and the fact that it is still there to remind us of how integral Farish Street was in any success you see in the realm of Black creativity, Black business, economic, and political autonomy—it started there,” Ebony Lumumba, department chair and associate professor of English at Jackson State University, said. “I’m grateful that the store has been able to withstand so many waves of opposition to Black progress, and it’s truly our talisman that we have still with us today to remind us of what we can achieve and what we have the desire to achieve as a community.”

In the novel The Help, white shoppers purchase a tell-all novel about Black domestic workers in Jackson at a bookstore on Capitol Street. Black shoppers purchase the book at a bookstore on Farish Street.

“We’ve been the only bookstore,” Primm said with a smile.

Marshall’s remained on Farish Street even as other businesses and community members began to abandon the area. “[Marshall’s] lives in a place that is so representative of Black genius and ingenuity. The Farish Street District was our Harlem, it was our Black Wall Street before integration… It was the epicenter of so much rich culture,” said Lumumba.

Following integration, many of Farish Street’s businesses shuttered. Newly able to access shops that had formerly excluded them, younger generations spent their money elsewhere. As older generations who had been loyal shoppers and patrons passed away, the younger folks were not there to replace them. Farish Street today is rife with empty and collapsing buildings; marked by faded signs for stores that have long been shuttered; and, except for on Sundays when the churches are full or when there is an event, largely quiet—something unimaginable only a few decades ago. In the decades since integration, Jacksonians have repeatedly been promised new development and revitalization in the area that have yet to come.

Photograph of Marshall’s Music and Bookstore © Shelley Justiss, adroitimages.com

The Farish Street District was our Harlem, it was our Black Wall Street before integration.

“The devastating part of that rich narrative is once integration took place and Black folks could take their business and money elsewhere, we saw the decline of Farish Street District until present day where it is truly a shell of what it formerly was,” Lumumba said. “But for our community members, those elders, and even those of us who remember some of the businesses as they were fizzling out, it’s still such a source of pride for us that it existed and was there.”

Farish Street does still have its mainstays: Big Apple Inn, where customers can get a classic pig ear sandwich; Johnny T’s Bistro and Blues; Central United Methodist Church and Farish Street Baptist Church; and Marshall’s Music and Bookstore—all of which have weathered the changing times. Marshall’s survived the Great Depression, the Second World War, Jim Crow, the Vietnam War, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and every other event in recent American history. The bookstore’s relationship with churches and its focus on serving the community have helped it survive. Now in its eighty-fifth year, the store welcomes customers—churches, specifically, Primm says—who have patronized the bookstore since the beginning and continue to do so today.

The relationships that Marshall’s early leaders developed with local churches’ leadership and parishioners have carried on through the generations. “We have churches that have been with us for so long that see what we’re doing in the community and call up and say, ‘We’re going to buy from you,’ just to support,” she said.

Shady Grove Missionary Baptist Church is one of those churches. When Frank Figgers, seventy-three, once a child patron of the store, grew up and became active in the church, he continued patronizing the bookstore that his mother had frequented before him. Figgers, a lifelong civil rights activist, worked with the Jackson Human Rights Project and has remained active at Shady Grove. He noted that since Primm has owned Marshall’s, the store’s collection has included more culturally centric materials.

“You can buy What Manner of Man, you can buy books about theology, you can buy books about history… There is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America,” he said. “You can buy books like that, which I think is a tremendous asset… You can get Kente cloth, dashikis. She has expanded the bookstore’s offerings.” He added, “They have a broad segment of books and related liturgical supplies that reach everybody, whether you are Baptist, Methodist, Apostolic, Church of God In Christ, Christ Holiness, USA—they have supplies that will meet anybody’s needs,” he said.

“That kind of commitment to community and the reciprocating of that community back to Marshall’s Music and Bookstore is what has kept us going,” Primm said.

Since moving to Mississippi, Primm has made her own mark on the state. Almost immediately after her arrival, she began getting involved with local politics. She worked on the campaign to exonerate the Scott Sisters in 2011 and also to free Willie Manning, who became one of six death row exonerees in 2015. More recently, she’s participated in efforts to highlight Jackson’s water crisis. The bookstore has been a key element in Primm’s activism. In addition to the constantly growing Black history walls, people know that they can come to the shop for her help, advice, and support.

Prior to the pandemic, each year she hosted Ashé Day, a nineteen-hour tour of the state of Mississippi. Starting in Jackson, participants rode a coach bus up to Utica, Mississippi, where Primm’s great-grandmother founded the aforementioned church, school, and burial ground. From there, they toured the state, stopping at sites until they reached the Gulf Coast.

“As a result, we would reconnect with ourselves,” said David Mosley, who participated in two Ashé Days. “It’s like reconnecting with your divine Black self.”

Now Primm, who comes from a long line of educators, looks to start a brick-and-mortar school, at which she plans to teach students true, in-depth Black history, as well as occupational and life skills. Although her great-grandmother started a school, her grandmother was an educator, and her mother and sister (both PhDs in education) were educators, Primm has chosen a less formal path, doing movable schools and teaching out of the bookstore. Until she opens the school, Primm will still be behind the desk at Marshall’s Music and Bookstore. There, she’s eager to educate anyone who comes in.

Each time I enter Marshall’s now, I’m greeted by Primm and the wall of Black history, yes, but also by a warmth that leaves me nostalgic for my elders and ancestors. Like generations of Jacksonians before me, I arrive ready to learn and to find knowledge I didn’t even realize I was seeking.