Ellen Gilchrist’s Real Man

An interview with the iconoclastic author

By James McWilliams

Someday We’ll Meet, 2023, oil on linen by Jess Allen © The artist. Courtesy Sens Gallery

In October of 2019 I drove from New Orleans to Ocean Springs, Mississippi, to interview the writer Ellen Gilchrist, who died last January at eighty-eight. Among her lifetime achievements—including the National Book Award in 1984—Gilchrist rejected two years of my requests to interview her about her relationship with Frank Stanford, the Arkansas poet whose biography I was writing.

“Absolutely not!” she would yell into the phone. “That all happened forty years ago and it’s none of your damn business anyway!” Sometimes she’d hang up in the middle of her own sentence. Then one afternoon, without warning or explanation, she called me and said fine, come to Ocean Springs. I left the next morning.

The quid pro quo was that I had to bring Ellen Gilchrist lunch. A Southern Salad from Newk’s sounds like a simple request. But Gilchrist revised this order with no less than seven specifications—half the dressing on the side, no croutons, extra tomatoes, go light on the chicken salad, so on—turning Newk’s Southern Salad into Ellen Gilchrist’s Southern Salad. As the topical ease of her prose masks underlying idiosyncrasies, so went her salad order from a strip mall in Mississippi.

Regarding those deeper idiosyncrasies, Gilchrist’s New York Times obit was gentle, noting her “lightly ironic” take on the “Southern upper bourgeoisie.” But Gilchrist’s loyal readers know full well that her idiosyncrasies—expressed in over two dozen books of fiction and nonfiction—were not lightly ironic at all. They were, like Ellen herself, absent of irony, bold, and critical of many progressive shibboleths.

A classic Gilchrist idiosyncrasy: Men are astounding. Men are worth losing your freaking mind over. And yes, men will almost always let you down. Men will, as Gilchrist’s character Rhoda Manning learns in Victory Over Japan, lead you into the woods and take your virginity and walk off with your cigarettes and ditch town. But they were still worth swooning over, those manly men, worth losing weight to impress, worth being at the center of your attention, worth the drama of lust, love, fidelity, infidelity, and the inevitable catastrophes men create for women dumb enough to care about them.

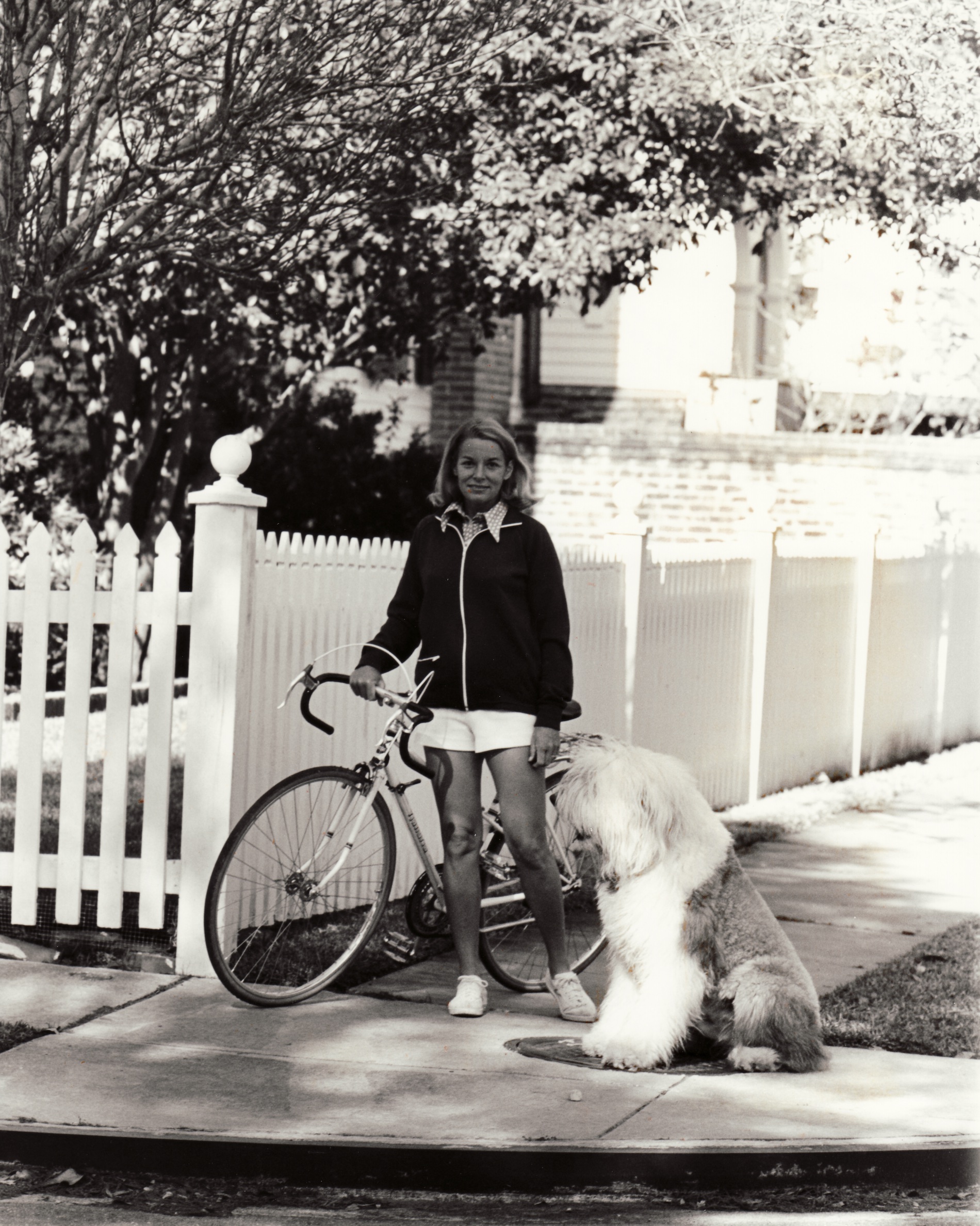

Photograph of Ellen Gilchrist courtesy Arkansas Memories Collection, Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History, University of Arkansas

“I like men,” Gilchrist wrote in Falling Through Space. “I suppose I should modify my statement,” she added, “and say that I like good-looking men who will kill or die for me.” For those who persist in seeing irony, she clarifies: “Down through the countless ages of human life, women have held the babies in their arms while men fought for them. This is not some sort of joke or cartoon. This is the reality of who we are and where we came from.”

This is, in other words, a conviction, and not necessarily one that expands the progressive mindset. Instead, it conforms to a larger worldview that, at least in Gilchrist’s fiction, celebrated a largely heteronormative ideal while failing to examine racial assumptions that smacked more of noblesse oblige than Black Lives Matter. Critics sometimes lampooned her for these blind spots, but she kept writing as if she could not have cared less.

To say that I find Gilchrist’s retrograde convictions ridiculous is irrelevant. Writing a biography, I’ve learned it’s best to take people and their work as they come. So as I stood there knocking on the door of Ellen’s oceanside townhouse, I sensed that not only was the heavily edited lunch order I held a litmus test of my manhood, but that Ellen Gilchrist—who answered wearing black tights, a baggy white t-shirt, her long red-gray hair in two pigtails, Bob Dylan booming on her CD player, and hips swaying—well, Ellen Gilchrist was bringing Ellen Gilchrist.

And what that meant—what it meant to be the writer Ellen Gilchrist—owed a debt to a man who loved women as much as Ellen loved men, a man Ellen would hug close for the last time on the morning before he went home and put three bullets into his chest: the poet Frank Stanford.

Ellen Gilchrist and Frank Stanford met in September of 1976 in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Stanford, who had taken two MFA classes as an undergraduate at the University of Arkansas back in 1969 and ’70, was a Fayetteville legend. He had recently returned to town to start his small press, Lost Roads Publishers, with his lover, the poet C. D. Wright. In the intervening years, Stanford, who was twenty-seven when he met Ellen, had lived in and surveyed the backwoods and small towns of the Ozarks (Eureka Springs, Busch, Rogers) and published seven books of poetry—crazed poetry of wild originality praised by the likes of John Berryman and Allen Ginsberg. Aglow with a national reputation, Stanford came back to Fayetteville as a long-lost hero. “To see Frank in the streets,” one grad student recalled, “was like meeting Marco Polo back from Cathay.”

Ellen arrived shortly afterward. She came to escape. At forty, she had done her time as the wife of a Harvard-educated corporate lawyer who had given her everything a good marriage was supposed to offer: ample resources, a big house in Uptown New Orleans, support for her healthy teenage kids (from a previous marriage), a maid, and plenty of free time to jog in Audubon Park and play tennis.

But she was miserable. As she began her MFA classes at Arkansas, she wrote to her friend (and father of Lucinda Williams), the poet Miller Williams: “I am abandoning as quietly and as neatly as possible this ridiculous marriage—it is very destructive to me to live with this nice decent capitalist jerk.” She wanted to be a poet. Just as urgently, she wanted to live the way a poet was supposed to live—cavorting and collaborating with other poets.

Gilchrist got what she came for in Fayetteville. With the help of Jim Whitehead, a poet and founder of the Arkansas MFA program, she discovered the crucible of the town’s artistic scene and was charmed by its bohemian plentitude. Fayetteville embraced her in return. Her friend, the artist Tracye Wear, remembers how “she was just always around.” Jessica Slote, a writer in the MFA program, recalls how all these young writers loved Ellen because she had already lived a life. “She had been divorced, married, and had children…she had life experience.”

She got plenty more of it in Fayetteville. Gilchrist studied Molly Bloom’s Ulysses soliloquy alongside a young guy from Montana, allowing how, after class, “I made love to him in an eighteenth-century graveyard on top of a hill near the campus. We were laughing the whole time.”

Other rendezvous were less successful. “Why are so many poets impotent?” she asked Miller. “All the ones you introduce me to are.” But these were rendezvous, nonetheless, adventures pursued among artists in clothes they hadn’t washed in three weeks rather than society ladies in pressed tennis skirts. Plus, who could complain when you were among so many young people who “were letting their hearts sing”?

It was Jim Whitehead who introduced Gilchrist to Frank Stanford, the charismatic nucleus of the whole Fayetteville fumarole, the man who would model for her more than anyone else the Byronic intensity of the poetic life.

Here was, after all, a real real man, a man who had written a single poem without punctuation that was over 15,000 lines long (The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You); a man who had once in a rage burned 10,000 pages of his work; a man who made an award-winning autobiographical film; a man with a wife and a mistress and a slew of lovers; a man who’d been institutionalized for losing his mind over poetry.

Frank was stunningly beautiful; his ear for poetry was beyond belief; he had gorgeous wild hair. Gilchrist saw in Frank not just a man who could kill and die for her, but a man who could recite Keats and kill and die for her. An early Gilchrist biographer called Stanford “the most influential person” in her life.

Gilchrist could be outspoken in her preferences. She was not shy about her politics. “I have always been a conservative,” she wrote. Her conservatism was more libertarian leaning than proto-Trumpish, and it could culminate in a smug sense that her success derived not from wealth or white privilege but exclusively from her individual work ethic. “You can’t be a pussy in this game,” she said, noting how tough it was for a writer to survive on her own. She combined her pull-yourself-up meritocratic sensibility with sexual politics that, in their liberated emphasis on pleasure—“nothing on earth, with the exception of great sex, feels as good as having written well”—complicated any effort to pigeonhole her as anti-feminist. Rather than reconcile her possibly contradictory positions, she was more content to be openly contrarian about them.

But she was shy about Frank. While she did tell the New Yorker in 2000 that “to know Frank then was to see how Jesus got his followers,” all she ever otherwise divulged about him was some version of this:

I knew a poet once and spent many days and nights with him and took walks with him and went into shops with him and watched the world with him and learned to adore the beauty of the world and despise its sadness. I must write about him someday…

Gilchrist’s moment in the MFA program was as brief as it was influential: She went back to New Orleans after less than a year in the program. And she never did write about Frank Stanford. Which is why I’d spent two years begging for an interview. Gilchrist let me into her house and walked me into the kitchen and lifted the lid on her lunch order, checking my work. She turned off Dylan, and our interview began with her answering a question I didn’t ask, nor even intend to. She pointed at my chest and declared, “I did not fuck Frank Stanford!”

First, I thought, Who cares! Second, I thought, So you’re the one person who didn’t! Third (since you brought it up!), I thought, Nobody believes you! I had it on good authority that Ellen and Frank did have sex, just once, and only because, as a close friend of Ellen’s explained to me, “she let him put it in so they could see what it felt like.” I adore this detail. I adore it not because it’s in any way salacious, but because it’s the opposite—so sweet and honest, so precisely what two curious friends might do to prevent the anticipation of carnal pleasure from interfering with what mattered.

It is hard to overstate how much what mattered for Ellen Gilchrist in the fall of 1976 really mattered. She came to Fayetteville as a woman on the verge of middle age needing liberation from bourgeois comfort through literature, and Frank was the only man she’d ever met who fully embodied the artistic freedom she envisioned. Here was a man whose manliness made art more exciting than sex.

For the next two hours in Ocean Springs I attempted to burrow into the sacred and life-defining connection between Ellen and Frank. I got nowhere. The more I asked Gilchrist precise questions about Frank the more she avoided answering them. In the meantime, a great deal of work got done: We ate our salads; I carried some heavy boxes from her living room into a closet; we drove to the post office to get her mail; we stopped by Walgreens to pick up medication. I took out Ellen Gilchrist’s trash.

By early afternoon, more than a little frustrated, I finally got her to sit down and be still at the dining room table and at least assume the position of two people acting as if they were going to do an interview. Then things got weird. She handed me a book and told me to turn to page 416 and read the nine-page story aloud. The book was Ellen Gilchrist: Collected Stories and the story was “The Uninsured,” a funny little piece about a woman who writes letter after unanswered letter to “Blue Cross, Blue Shield” discussing the implications of allowing her coverage to expire. Ellen laughed as I read, her eyes gleaming when I laughed with her.

The woman in the story’s name is, again, Rhoda Manning. The name appears no less than twelve times in the story and, yes, what was happening at Gilchrist’s table was gradually dawning on me: Ellen Gilchrist was indeed bringing Ellen Gilchrist, but she was doing so via Rhoda Manning, an autobiographical stand-in who animates much of Gilchrist’s fiction.

The only downside to this elliptical form of communication was that I now had an ample reading assignment. Fortunately it didn’t take long for Ellen’s (somewhat repetitive) bibliography to reveal that Rhoda Manning had a thing for a male poet named Francis Alter, and it took even less time for me to recall that Francis Alter happened to be Frank Stanford’s name before his mother, Dorothy Alter, married Albert Franklin Stanford in 1952. In “A Wedding in Jackson,” Rhoda says of Francis Alter, “He was my first true writer friend. The first blessed, gifted, cursed poet that I knew. Also, the most beautiful human being I have ever seen.… He dedicated his life to beauty, to art, poetry, freedom. Then he killed himself.”

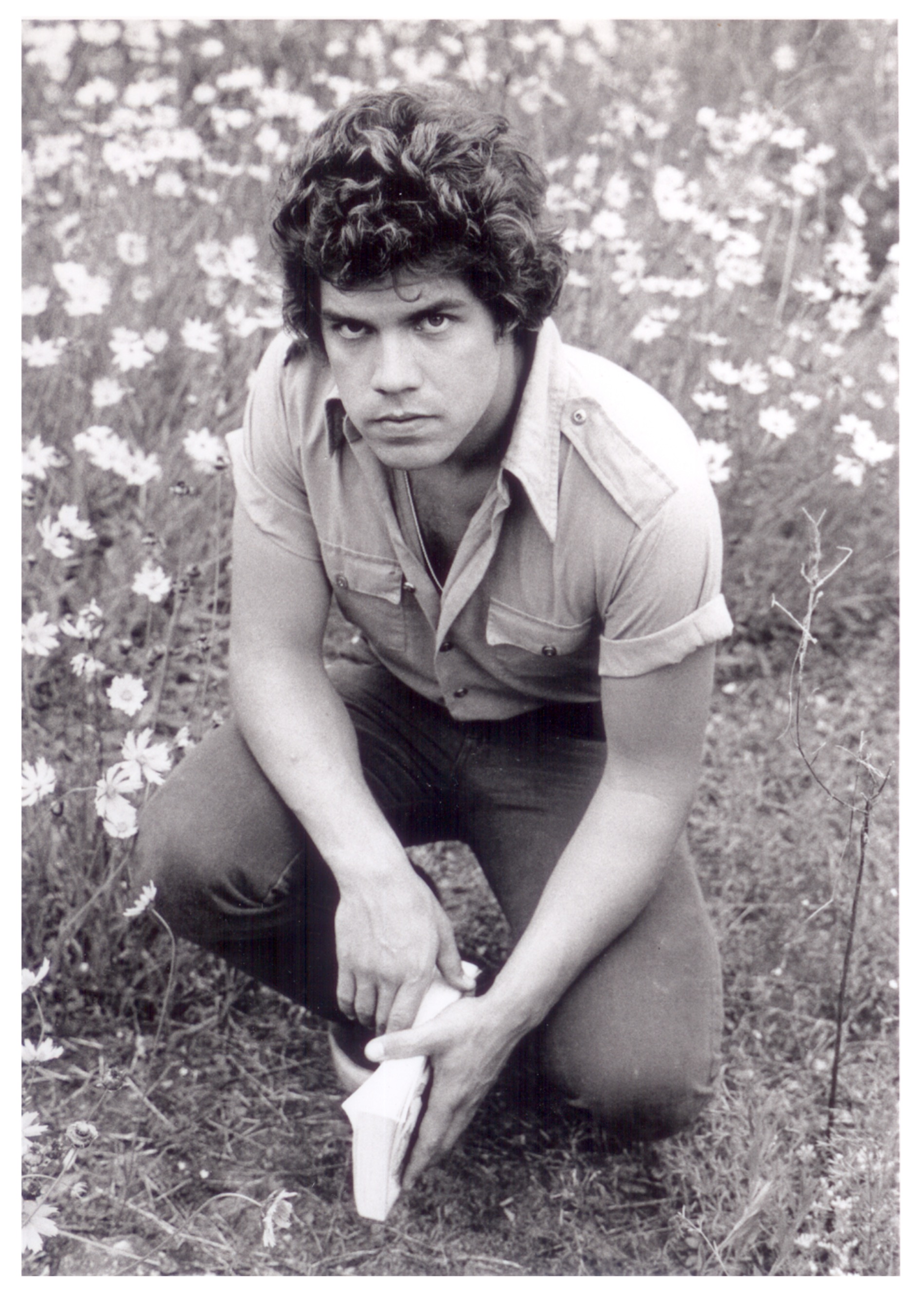

Photograph of Frank Stanford, 1973, by Ginny Crouch Stanford. Courtesy the artist

Right before he did so, Frank Stanford visited Gilchrist for two weeks in New Orleans to put the final touches on her first book. This thin volume is a selection of poems called The Land Surveyor’s Daughter, and Lost Roads would publish it in 1979. During this visit, Frank and Ellen (and others) went to hear music at Tyler’s Jazz Club and the Maple Leaf Bar, buy books at Maple Street Bookshop, and see a performance at Rosy’s Jazz Hall. Frank rode the streetcar alone at night, up and down St. Charles, enthralled.

Gilchrist told me that Frank went over her poems hundreds of times, getting them as right as he could. “He had the perfect ear,” she said. As for Rhoda, Gilchrist writes in her story “Going to Join the Poets” that “she had [Alter’s] friendship and his help with her work. It was a gift she had longed for all her life.” And in “A Wedding in Jackson,” Rhoda further says of her beloved Francis Alter, “He showed me how to make my first book.” Gilchrist, if only through Rhoda, was being as clear as she could be with me: She became the writer she did because of Frank Stanford. As we talked at her dining room table, she told me she remembered him sitting on the floor of her house in late May of 1978, scribbling away on a legal pad, page after page. How beautiful he looked. She could not have known then that he was likely writing one of his suicide notes.

As I prepared to leave her townhouse, I handed Gilchrist my 1979 first-edition Lost Roads copy of The Land Surveyor’s Daughter, a rarity valued around $600, and asked if she would sign it. She nodded, took it from me, and dropped it into the trash. Then she told me something I did not know.

By late May of 1978 Frank and Ellen, after hours of close reading together in New Orleans, had gotten her book’s thirty poems right where Frank wanted them. He seemed thrilled. But between Frank’s death and the publication of The Land Surveyor’s Daughter in 1979, something happened that forced Ellen to disown the Lost Roads version of her book, which was why my copy was sitting in the trash can.

The poet C. D. Wright, Frank’s lover, ran the press alone after Frank’s death. Before sending Gilchrist’s book to the printer, Wright cut two poems from the manuscript and tinkered with a few others. The alterations were quite minimal and may even have improved the book. But, as Ellen saw it, that wasn’t the point.

To make sure I understood what her point was, Ellen Gilchrist ended our interview by doing two things. First, she handed me a copy of her self-funded revised edition of The Land Surveyor’s Daughter (1980), a book restoring the text back to what she had done with Stanford. Second, she invited me upstairs to her bedroom.

In her boudoir she sprawled on her bed and had me sit in a chair at the foot of it. She gestured to the small bookshelf to my right and had me take down What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford. Before she asked me to read Stanford’s poem “Linger,” Gilchrist told me that on the morning of June 3, 1978, after she and Frank had worked on getting her book ready for prime time, they went to breakfast on Magazine St. and Frank, before heading to the airport, gave Ellen an unusually long hug and said, “Goodbye, this is really goodbye.”

Then Ellen ordered me to read the poem, noting that she was about to fall asleep and, when she did, I was to lock the door from the inside and let myself out.

My god she chose a beautiful poem. I read it slowly, anxious to prove myself capable, a real man, if not a real real one, and when I got to the last stanza—

The animals wade the creek

And eat blackberries

The wind blows through the trees

Like a woman on a raft.

Ellen was asleep. She was smiling. Quietly, I went downstairs, made a pass by the trash can, wrote a brief note of thanks, and then, doing exactly what Ellen had been asking me to do for two years, I left her in peace.