The Flirt

By Rebecca Bernard

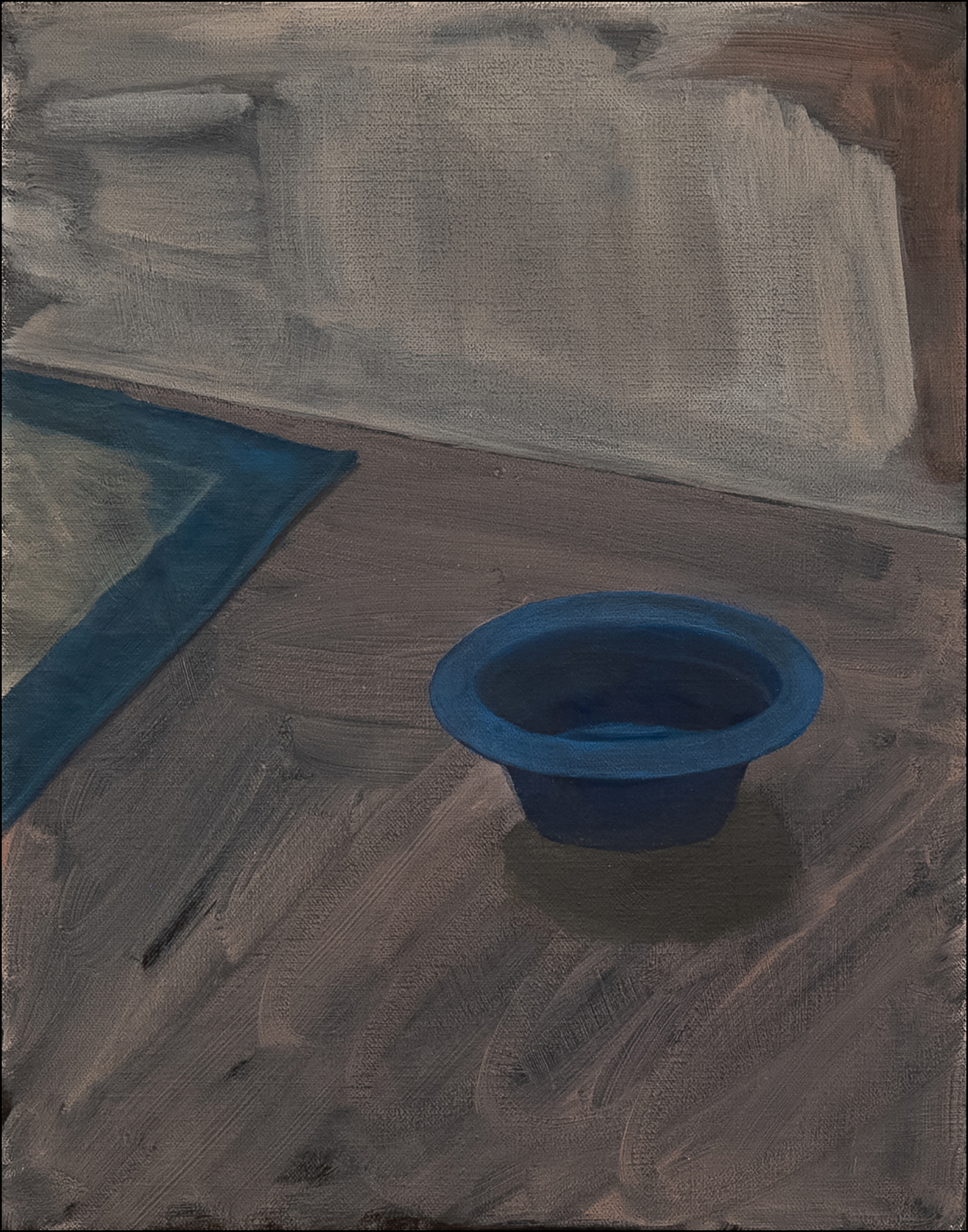

Well-grounded, 2023, oil on canvas by Erica Vincenzi. Courtesy the artist and La Loma Projects

A t forty-five she has become what she never was before: a flirt. A holder of eye contact, biter of lower lip. A woman who laughs to expose her throat, still taut somehow thanks to early sunscreen, to neck exercises when she does the dishes, to holding her head high despite the desire to shrink or weep. Meaning, despite all odds, she still feels pretty. Prettier even than when she was in her twenties honking loudly at the world: hair in braids down her back, bell bottoms fraying where they met the earth, tinted Beatles glasses settled on the tip of her average-sized nose. A caricature of a hippie, but she believed in everything she said, incensed by the world’s inequity. She feels freer now, as if losing her teenage son were akin to dropping the ballasts and there goes the balloon, up up up. There goes Marcia Marcia Marcia. A name she’s just coming around to loving, if not in her own mouth, on the tongues of strangers.

Because what are strangers if not a kaleidoscope of possibilities, other lives, sliding doors, people that her son might have become. Given the chance.

Tonight she wears a suit: tight pencil skirt, soft off-white silk blouse, black blazer, black pumps with a modest two-inch heel. Nothing fast about her fashion, she likes to joke. And this is the audience for it—the climate crowd. Her train to Philly got in late, taxi to the conference hotel, strategic seat at the not-yet-crowded-or-no-longer-crowded hotel bar. She orders a chicken Caesar salad, a gin martini with olives. Closes her eyes for a dramatic, decadent minute, then opens them. Sips.

Up in the room fifteen minutes earlier, dropping off her bag, she’d called her husband from her new cell phone. Useful these cell phones, helpful tethers. How was their daughter Erin doing? Asleep at a friend’s house. Good good. What had he eaten for dinner? A baked potato and a steak on the grill, some baby carrots. You miss me? He did. And she missed him too. A missing palpable as a lump on the throat, a goiter. Call me tomorrow? She would. Then I love yous, which she knew both of them still meant, lucky ducks. To still love your person five, ten, twenty years down the line. How few loves, she knew, were capable of surviving a child’s death.

She drinks enough of the martini to feel wispy before she takes her first bite of salad. Crunches the greens in her teeth, the end of a crouton.

People are scattered around the bar tables—high two-tops and some low-slung glass numbers with armchairs pulled up. A few people sit at the bar like her, but no one sits on either side of her. A chair away to her left are two younger women, maybe mid-twenties, with glasses of pink wine. At the far end, an older man with an open laptop. Three seats to her right a young man, late twenties just shy of thirty, sitting with a tumbler, watching a screen above them. She studies him for a moment longer than necessary then checks the screen. Basketball. Men running in swishing red shorts. Floor squeaks she can’t hear with the sound off. She takes another bite of her salad. Someone at a far table laughs loud enough to make her think to turn, but she doesn’t. Lights from traffic outside periodically cast beams through the windows.

“You here for the conference?”

Everyone’s opening line. The timing, maybe a record. She turns to the man to her right and nods. “Not presenting anything, just for a couple meetings. I’m with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. You?”

The man nods, still looking at the screen. Brown hair in need of a cut or it’s intentional, the drifting over the forehead into the eyes. He smiles, maybe from her gaze. “Pennsylvania Sea Grant. And I’m on a panel about community involvement.”

She takes a bite of chicken, feels the sharpness of her teeth tearing the bird’s flesh. Her next sip finishes the martini, and she signals for one more. Three-day conference, so it’s best to go easy the first night.

The man returns to his game. Peace again.

Or something else. Anticipation. The game before the game. She wiggles her toes in her pumps. Imagines the bed upstairs, a waiting king. Allows herself her once-daily thought of Ryan—not as he was as a baby, toddler, boy, teen—but as what he might have been. Say at forty, his own son strapped to his back, hair thinning like her grandfather’s. Look what I gave you, she’d think, running her fingers over his scalp, the chance to grow middle-aged and ugly. To be someone else’s worry.

She sighs on accident, the escaped air a little piece of herself—something utterly private, molecules that have been inside her body’s deepest reaches.

“You come to a lot of these?”

Just wait, little boy blue. She takes a moment before she turns to the man and nods. “Lately, yes. You?”

“Same.” He shakes his head. “One good side effect of Bush at least. People are angry, they start to care about the environment. More money floating around.”

Marcia pushes her drink against her lips. “It’s nice when people care.”

“You been doing this long?”

A couple comes up to the other end of the bar, and the man from the Sea Grant points to the chair beside Marcia. “You mind?”

She doesn’t.

He settles beside her. He raises his empty glass toward the bartender. She can smell him now, something nerdy, earthy.

“I’ve been with the Bay five years. But doing this work for…twenty? I took breaks when my kids were born.” She sucks an olive into her mouth. “Got into my current position three years ago when my oldest, my son, died.”

The man studies the screen overhead. Accepts the new drink and swallows before he says anything. “Jesus. I’m sorry.”

She doesn’t reply. His eyebrows are thick, a cowlick causing the left one to rise unruly. He’s not classically handsome, but his nose is well-shaped, his eyes probably his best feature. Face clean-shaven in a boyish way.

“What’s your current position?”

She moves her tongue slowly over her lips as if feeling for her lipstick. “I’m a grants manager.”

“How old was he?” The man turns to look at her. Yes, his eyes. Gray-green like her husband’s, her son Ryan’s. “If you don’t mind me asking.”

“Fourteen. Almost fifteen. It was an accident. A fire.” She sucks at the inside of her cheek. “I only say something because it’s funny not to, if that makes sense.” She picks up her new martini. “Like I’m lying.”

“I think I understand that.” He pops an ice cube into his mouth. Returns his eyes to the screen.

A strangling feeling in her throat that she soothes with another sip of her drink. She rolls back her shoulders. The thoom of her heart settling to its banal normal. She calms herself imagining her husband placing his single plate in the dishwasher, the cool breeze drifting in from the open window over the sink. A suburban dog barking its suburban bark.

“I’m newly separated. That’s my secret power.” The man’s returned his gaze to her now, leaning slightly closer. His gray blazer hangs on the back of his chair.

Marcia considers his revelation. Considers the gold band on his left ring finger. At her look, he self-consciously turns the band.

“It’s new, still.”

“I get it.” She reaches over and pats his wrist. Acute, motherly.

“It’s nice to have this excuse.” He gestures at the bar, the hotel. “To travel, I mean. Keep myself occupied, away. I could see that in your case, too.”

She presses her lips together, allows a faint smile at the corners. Imagines the man before her as a boy, a high schooler, what would he have been like in college? Good to women, she senses. Divorced now from marrying too young—she’d have advised them to wait if she’d been asked.

“Did you grow up in Pennsylvania?” She shifts her body a degree away from him.

He shakes his head. “Delaware, but I went to Temple, so.”

“I’m from upstate, but we’ve been in Maryland, Silver Spring, for what feels like forever.” She swallows more martini. “A stint in New York, then D.C., and voila, the suburbs.”

The man turns to her and holds out his hand. “I’m Brian.”

A tinge of perspiration on her palm, she takes his hand, squeezes. “Marcia.”

“Marcia, Marcia.”

“Something like that.” She rolls her eyes, forgiving. “How did you get into working with the Sea Grant?”

He swishes his drink, then swallows. “I’d guess it’s the same as most of us here.” He looks up at the screen, milk mustachioed Angelina Jolie beams down. “I loved nature as a kid, the ocean and all the animals. And my aunt had a connection.” He shrugs. “I’m grateful to do something I care about.”

She nods, understanding. He isn’t as earnest as he might be, but there’s something she likes about him. Maybe the sloppy hair or that he still wears the ring. “I think I’ll have one more.” She taps on her glass.

The bar begins to fill up again with the late rush and the energy buzzes around them. An older woman with neat, white hair takes the seat to her left. The couple beside Brian lean close together, fingers entwined on the bar top. The two women’s glasses refilled, bright bubbling.

The sound rises, happy energetic hopeful. Talk of saving the earth, the turn of the millennium still fresh in everyone’s mind, Y2K one threat never materialized, maybe the others just as liquid?

“Let’s play a little game?”

“What’s that?” he leans closer to hear her.

His breath—mid-priced bourbon, familiar, like the backseat of a parked car. “I said, want to play a game?”

“A game?” He blinks, then looks to either side of him, teasing her. His eyes just a titch glassy. He turns back, places both hands on the bar, palms down. “Why not?”

"Great.” She takes a final bite of her salad then pushes the plate away, pats her mouth with her napkin.

“What kind of game?”

She gives him a long dissolving look, tries to, her eyes also her best feature, face canted just so, faint smile, left eyebrow raised, lips suggestive. “You’ll see.”

He blushes, eyes down to his ring finger, twisting. A sweet tic. “Guess I picked the right seat at the bar.” He moves his hand toward hers but she pulls away. “Sorry I?”

“Do you smoke?” She sits up, straightens her blouse.

“Sometimes. When I drink.” Sheepish face, errant boy. “I have a pack of American Spirits if you want one?”

She takes her new drink and taps it against the man’s drink. “Why not?”

She drains the glass, feels the muscles of her neck contracting, doesn’t stop till the gin’s all gone.

Ryan as a baby, seven months old. A fever just low enough to remain unconcerned, just high enough to cause panic. She remembers blowing on his face, wanting to rub an ice cube against his belly. How silent he was in his suffering, hot little hands flapping but not even a single yowl. Her boy, a seashell, a hermit crab. How she went to their bathroom to weep with the door closed after passing him off to his dad—ashamed at her failure.

That she could think of that as failure. Imagine.

Awful, 2023, oil on canvas by Erica Vincenzi. Courtesy the artist and Giovanni’s Room, Los Angeles

She remembers blowing on his face, wanting to rub an ice cube against his belly.

Ryan at nine, a Christmas in New Jersey at Uncle George’s house, and no one could find him for a full hour. How he’d tucked himself behind the stairs with a Rats of NIMH book. How when she finally discovered him, he’d tearfully explained that the book had made him sad and he didn’t want his sadness ruining anything for Erin, his little sister. Yes, he’d heard them calling his name, but he felt embarrassed and he hadn’t known what to do. His mouth half open, his body paralyzed, though that wasn’t the word he used. He’d said stuck. How she folded him into her arms. I will always unstick you, silly. Silly.

Ryan at fourteen, sensitive, sure, but well-liked. Careening around the cul-de-sac on his skateboard with Tommy and Malik, ripping a hole in his jeans and offering to sew it up, to learn how. Together deciding that rips were cool—it’s okay, Ry. A girl, she thinks there was even a girl he liked who liked him back, is grateful he had that. Remembers her heart-shaped face at the funeral, curly hair, prominent freckle on her collarbone. Ugly in her grief, but lovely too. Had her son kissed that freckle? Known the intimacy of touch in that way?

She hopes so.

She and Brian find a sheltered spot to stand beneath the hotel’s awning. Early spring and the air’s on the chilly side, wet with the promise of spring.

She allows him to shield the flame from the breeze, turning away to exhale once the cherry glows red. The wind whips and how wonderfully exposed she feels. Raw and dangerous.

He inhales like a real smoker, and she appreciates this, just as it worries her. Would her boy have smoked? Likely as a social grace, but quit later, hopefully without too much trouble. As she had done, as his father.

“You shouldn’t do this.” She gestures with her cigarette. They stand close together, maybe a foot apart.

The man gives a wry smile. “Which part?” Meets her eyes and she feels a stickiness in her chest that makes her turn away.

“I’m kidding.” He brushes her shoulder, reassuring pat. “I’m quitting on my birthday—I turn thirty in October, so, goodbye bad choices.”

“What a birthday gift.”

Brian, the man, laughs. Easier to think of him as the man. Like any boy could one day become any man.

“So what’s this game we’re playing?”

She exhales. Feels briefly luxurious, French. Her new slimness a side effect of death, one day nothing in the closet fit, her prior self dissolved. “What were you like in high school?”

“High school?”

“Sure. What kind of boy were you?”

The man considers. In his blazer, he looks younger still, the fit imperfect.

“Is this the game? Twenty questions about my life?”

“Not exactly.” She feels the buzz from the cigarette keenly. The headiness makes her smile, and the man steps closer to her. Their edges touching.

“You’re pretty.” He smooths her hair. “I mean, I find you quite striking.”

“Are you flirting with me?” She tilts her head back, knocking his hand away. Exposes her throat, lifts her chin to him.

“Am I?” He steps back, shakes his head. “I thought so, but I’m out of practice.”

“I could be your mother.”

“But you’re not.” He faces her, takes her free hand and pulls her so that she’s inches from him, so little space between their bodies.

She’s surprised by his roughness, his directness.

“What if I said the game was about roleplay?” She steps back, freeing her hand from his. Takes a long drag on her cigarette then squashes the butt with the toe of her shoe.

“You want another?” He holds out the pack, and she shakes her head. He pulls out a fresh one and lights it with the end of his first.

She watches him bend down to pick up her butt and walk over to place it in the urn along with his. “Thank you.” And here the thoughtfulness. A tearing feeling in her chest, paper doll ripped at the edges.

He returns to her and shrugs. “The earth and all.” He studies her and she does her best not to move, not to let her face betray herself. “I was a bit of a punk in high school, honestly. Not too bad or anything, but I liked going to shows, safety pins. Cigarettes and all that.”

“Did you skateboard?” She blinks, the wind wetting her eyes.

“How’d you know?”

“A hunch.”

He takes a drag and blows the smoke above him. Then he moves toward her again, gets so close he’s upon her, overtaking her almost. “So who is it you want me to be?”

She swallows the saliva in her mouth. Reaches for his cigarette and takes a drag, the intimacy of the wettened filter. “Do you want to come up to my room?”

He takes back the cigarette. Turns to the street. Cars pass even though it must be close to eleven by now. Fully night. People, tourists, wandering out for late meals, drinks. He turns back to her, his face a little sad, if she’s honest with herself.

“Or is it that you want to be someone else?”

She pictures her husband in their bed, snoring, turning. Waking to her absence and back to sleep, trying to.

“No. I’m me. A version of me, at least.” She hesitates, then takes his hand. “But you could pretend I’m someone else. I don’t need to know.”

“Consider me intrigued.” He puts out the cigarette, half finished.

She turns toward the hotel’s entrance. He’ll follow, she feels it.

She straightens herself, walks carefully, one step then the next. The way we walk when we know someone else is watching. Her body the lure and for how much longer.

He’s behind her. “Can I ask his name?”

The automatic doors swoop open, the warmth of the interior bright, alive.

She shakes her head. “No. You cannot.”

Ryan at four, lying on the soft carpet of the family room, gently petting Tammy, the calico stray they’d adopted the month before. Gentle pets, truly, which was not typical she knew. Other kids grabbed, squeezed, unaware of their budding strength. But Ryan was slow, careful. The doorbell rang and startled the cat, startled her as well, a neighbor returning a casserole dish. A long scratch down Ryan’s bare arm, but no cries. Silence so that she didn’t realize he’d been hurt until she asked him if he wanted a snack, and there was the streak of red blood, the eyes wet, his mouth mumbling sorry kitty, I’m sorry. Sorry. Always her little boy blue.

Ryan at eleven, home sick with the chicken pox. Apologizing for making her miss work. Complaining not of the itching but that he’d spread it to Tommy not knowing that he was sick, nothing yet on his skin to mark him. Baby, it’s not your fault. But she could not convince him. He sat in the bathtub alone, too old for her care, refusing the oatmeal, the calamine. Telling her he deserved it, and how powerless she’d felt. Powerless to the point of anger—she’d yelled at him, hadn’t she? Made it all worse.

Ryan at fourteen and eleven months. Unrecognizable beneath white wrapping, gauze. A sulfurous smell like brie forgotten for months in the fridge’s deepest recesses. A howling that was her own voice. Vomiting daily, like morning sickness. Mourning sickness, a thought she couldn’t bring herself to say aloud. And yet just before, fourteen and ten months, a beautiful child, kind, sweet, eating a slice of watermelon over the sink, red juice dripping, babysitting his little sister, taking out the trash without being reminded, maybe engorged with sadness, maybe. But maybe not.

“Why did it end?”

They ride alone in the elevator, a grace she’s aware of. Standing apart as the floors tick upward.

“She fell in love with someone else. A woman actually. I guess maybe she and I were always just really good friends, and I mistook it for more. Or I wanted more.” He looks at his shoes as he speaks. Black dress shoes, a little scuffed.

“I wonder if that makes it more painful or less. That it was a woman and not another man.”

Brian turns to her. The elevator lights golden, casting halos on both of them. “I lost the person I loved. I wonder if it doesn’t matter how.”

She blinks. Looks at her reflection in the mirror. Smooths her skirt. Ignores the wrinkles at the corners of her eyes, how prominent they become the more tired she gets. “It can matter.”

At the door to her room, she fingers her keycard, hesitating. Pivots so her back is against the door. The man looks at her curious, maybe surprised by this hesitation. “You still want to come in?”

“I followed you up here.”

She closes her eyes. He leans forward as if to kiss her, but she stops him. Pulls him close instead, hugging him to her. “You should know I probably won’t sleep with you.” She whispers this, has to say it, she knows. Otherwise.

She’s not really a flirt, not really. But flirting gets her what she wants.

“That’s okay.” Brian holds her back.

“All right. Come inside.”

The first time, five months after the death, in a hotel in Reno, a man her own age who’d lost a daughter in a car accident. I’ll be her if you’ll be him. They held one another. Asked questions. Tell me about your wedding, the birth of your first kid, the promotion at work. Basic, banal, wonderful realities to live in. If only briefly, if only fantasy.

The second time, a man in his sixties in Connecticut. Well-groomed, kind. Willing to pretend to be her son, strange how many people were willing, though some weren’t. Some gave her wild looks, sick woman, when they realized what it was she wanted. But this man had waxed on about his career, an environmental lawyer, talked about the island in Maine he visited, how happy he, Ryan, was in this alternate life. Often the ones who lost someone understood best. What harm in pretending for an hour or two, to get to meet her boy all grown up, or on the way.

The fifth in Philadelphia, a man almost thirty, recently heartbroken.

Another drink might be useful but there’s no minibar, only a bed, a chair, a desk. He sits on the edge of her bed so she takes the chair, and he looks confused at her distance, but she smiles, slips off her shoes, exposes her stockinged feet.

She takes a breath. “You look a little bit like him. If I can say that.”

“You mean your son?”

She nods. Sees him glance at the door. But he doesn’t move.

“I can’t really think what it must be like for you.” He kicks off his shoes, one then the other. “I mean, I can try, but not really.” He squeezes his hands together. “My aunt had a stillborn, and it messed her up for a while, but that’s different. I mean she never got to know her.”

“It’s still a loss.” She bites the inside of her cheek. “What’s she like? Your wife.”

The man lays back so she can’t see his face. His arms stretch overhead. “She’s funny. I mean, really funny. She wrote for our college humor zine. I don’t know. Her hair is close to your color, shorter though. She likes to eat. Not even good food or anything, but like she won this hot dog eating contest once.” His arms drop to the bed. “I really don’t want to think about her.”

Slowly, Marcia stands. Drapes her blazer over the chair. She moves to the bed and lies down beside the man, slightly more than a foot between their bodies. “I’m sorry. Sometimes it helps to remember, but not always.”

The man turns on his side, propped up on his elbow. He stares at her and she accepts his gaze. Closes her eyes. Feels a pain in her throat, but doesn’t swallow, stays perfectly still.

He says, “You know. They say confidence can make people appear more beautiful, but I think grief does the same thing.”

His hand on her hair, her side, tracing her. She sucks in her breath, a piece of glass on the table, breakable, that’s what she is. His hands on her back, her throat, tracing the edge of her ear. Then a retreat. His hand gone. Her body all alone.

“Her name’s Amelia. I forget how lucky I am that she’s still alive. Even if she doesn’t love me anymore.”

She can’t speak but she nods, eyes still shut tight.

“Do you want to tell me what he was like?”

She shakes her head.

“You want to keep that for yourself.”

Yes.

“You want to pretend I’m him? If he’d lived this long? Is that the game?”

She gasps. Whatever’s dammed up, breaking. Neck loose, mouth open. She sits up. “Can I hold you?” She opens her eyes, and he’s before her. Gray-green eyes on hers, hand reaching out, hair in his face. He nods.

She cradles him, holds him tight, too tight at first and he resists her, but then readjusts himself in her arms, and then gentle, gentler. His head against her chest. Almost too big for her, but not quite; she can offer comfort yet. “I’m sorry, baby. I’m so sorry.”

The man sighs against her. She strokes his back, it’s okay, it’ll be okay.

“What do you want to know?” he asks her.

“Oh, Ryan.” Tell me everything.