The Frogs

By Kaylie Saidin

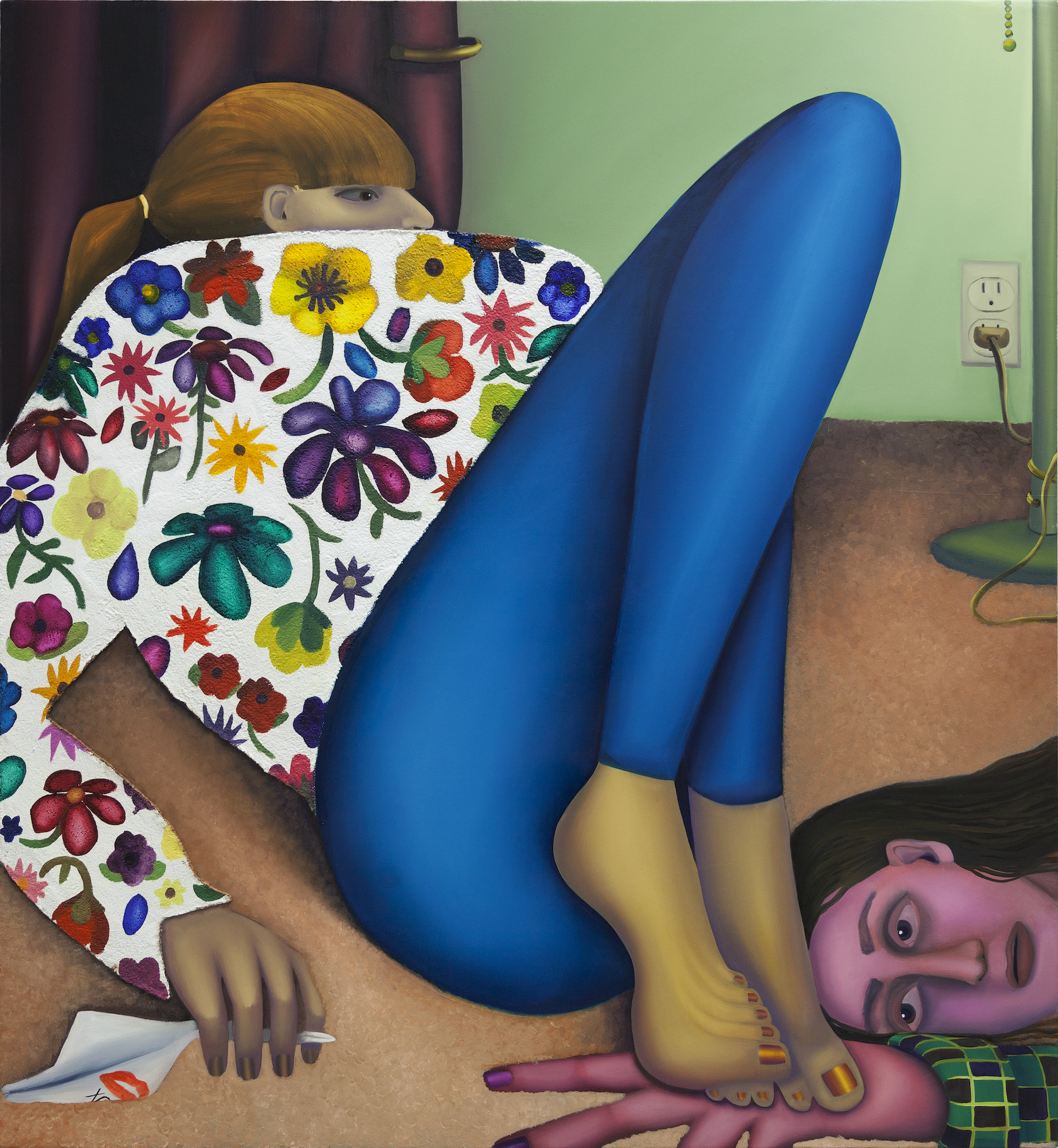

Rumors, 2019, oil and sand on canvas by Coady Brown. Courtesy the artist and Nazarian / Curcio

In the year after college, a rotund and mossy-colored toad stood at the bottom of the wooden steps of our condo every evening without fail. I’m not saying I’m a toad expert, but it was the same toad each time. You’d know him if you saw him. He would come out at dusk and stare at something imperceptible, occasionally letting out a bloated croak. By morning he would be gone.

My roommate and I argued about what to name him. She wanted Fabio and I wanted Alexander. We compromised by referring to him as “Our Friend,” or sometimes “His Highness” when we were feeling silly. After she went to bed, I’d sit at the bottom of the stairs and drink a beer, staring at Our Friend. I almost expected him to speak to me, but he never did.

Each night when the sun receded behind the trees, the water and grass and swampy vegetation around our complex would become covered in frogs of every shape and size. They were deafening at night, but we were used to hearing their chorus at all hours. So, when they seemed a bit quieter one day at dusk, I noticed.

“Hey,” I said to my roommate. “Is it me, or are we missing some frogs?”

Her phone was buzzing, blaring the intolerable ringtone meant to sound like a piano bar, and she held up one long, manicured finger. I hated that—when she communicated with me via hand signals. Her face was apologetic, though. She had one of those faces that gave away what she felt.

“It’s Stacey,” she said, and stepped onto the balcony with her phone pressed against her sunburned cheek.

My roommate was in the midst of a sordid love affair. The man she loved was named Stacey, which was humorous enough, though I never said so to her face. He was the president of the local beekeeping society. He was handsome in a boyish way, and I always imagined him with hands that were perpetually sticky, a face obscured by a dark protective net. I had only met Stacey twice: once early on, when he showed up to court her, and then when he appeared at the door holding a bouquet of zinnias to apologize for something.

The problem my roommate faced was that Stacey was engaged to someone else and had been since the summer after college. “It’s an issue of his love,” my roommate said. “He has too much love to give.” He loved my roommate and wanted to be with her, she explained, but he could not leave his fiancée: he was afraid to break her heart.

“Say he never leaves this girl,” I’d tell her, in my bolder moments. “Say we wake up one day and we’re thirty, and he hasn’t left her. Then where will you be?”

“Can you stop calling women girls?” she’d retort. “We’re twenty-three. We’re women, not girls. It’s so…entrenched in the patriarchy of you.”

Then we’d spiral into a different argument, one that was really about something else, and I’d leave the room and walk down the stairs to the pond and talk to the frogs. They listened better than anyone else did.

It didn’t really feel like we were women. One morning I’d opened the dishwasher and been hit with a wall of water, like a small floodgate had burst. Our galley kitchen floor was then covered in a one-inch-deep pool, which we’d soaked up with every towel we owned (a total of six). The garbage disposal was broken, the sink overflowing with brownish water. When I stuck my hand down the drain, I touched glass. I siphoned up a shard of a shot glass we’d used the night before. It had once read CANCUN in neon letters, and now the shard simply read UN.

“Deus, trois,” my roommate said, walking in with a messy bun and holding a mug of scalding tea. She’d studied abroad in Paris, and subsequently had never stopped talking about it. She looked at the kitchen. “Fuck. We’ll have to text Robert.”

Robert was theoretically our landlord. We had never met him, nor had we spoken to him on the phone. The condo had been passed down to us by elder college students who, coveting the cheap rent, had moved back to their quaint hometowns after graduation. None of them had met Robert either. Actually, we had no real evidence to indicate that he was a real person and not a robot, or perhaps an alien.

Sometimes, after eating too many gummies, my brain circled back on the notion that we were part of an alien study: that the condo functioned as a diorama, with microscopic cameras and microphones throughout, and extraterrestrial scientists stood above us with clipboards as we interacted with our simulacrum and fumbled our way through our lives. Robert wasn’t the head scientist; he was probably just the communications director, the one who had the best grasp of the English language and the nuances of email etiquette. The situation reminded me of sitting around and waiting for Godot.

My roommate held her phone out for me to see. She’d typed a message that read, Hey, Robert! It seems that something is not right with our garbage disposal, and there is water everywhere! If it’s not too much trouble, could we perhaps have a plumber come take a look?!! Thanks!

He responded, uncannily, within moments.

Plumber coming tomorrow Text if any problems Robert

“Isn’t it weird he never uses any punctuation?”

“As opposed to your exclamation points?” I said. “Your message was like, a minefield of exclamation points. In the musical of your life, you’d have an exclamation point at the end of the title.”

“I’m being pleasant,” she said. “You could try it sometime.”

Neither of us were employed in any real sense. My roommate was a hostess at a fancy seafood restaurant that catered mostly to tourists, and I made paltry money working as a driver for a courier app, delivering college students’ fast food at odd hours. She was constantly doing job interviews for marketing positions and similar jobs that valued her cheer and exclamation points. I, on the other hand, was content with both my minimal-commitment job and with being unpleasant—nothing was worse to me than being false.

My roommate and I had not been friends in college. I’d known who she was, though. She’d been in a sorority with housing adjacent to my dorm building. She led some sort of weekly aerobics group on the lawn, and on Sunday mornings, I’d peek out the window and see her and ten other girls lifting tiny pink weights.

We never had class together—she was a business major—but she was well known in the journalism department, because she had gone viral. In what started as a makeup tutorial on highlighter, she name-dropped a fraternity brother who’d been known to dose drinks and accused the Title IX coordinator of burying complaints about assaults at the on-campus frat parties. The video was titled “Why the fraternity system should be abolished.” It got nearly a million views and some national press coverage, and the Title IX coordinator resigned.

We didn’t have opinions of our own, as journalists—we were trained not to by our formidable department chair—but we were all in awe of my future roommate. Our interview with her about the video brought the highest-ever campus engagement with the newspaper.

As the years went on, I saw her at the bars around campus, always surrounded by girls wearing strikingly similar outfits. She ordered Long Island Iced Teas, which I felt was a signifier of an unstable personality. I also heard that she had a pet rat named Sartre, after the French philosopher, which further bolstered my theory.

I learned, upon moving in with her, that she was ambitious and often talked about moving to New York someday to work in brand marketing. She was funny, but mostly in action—like her facial expressions when she tried to clean the oven. She used an arsenal of bath and skincare products that lined the tub and the countertops of our shared bathroom. She always said how she felt. I got used to her emotions being perpetually visible, a bloody heart beating on her sleeve, and balanced them with the emotional state I knew best: stone-like placidity. The only thing we had in common was that neither of us were going back to our hometowns, because there was no home for us there anymore and hadn’t been for a long time.

The condo was in the north center of town. Our building crawled with small cockroaches that we killed by pressing our fingertips to the counter. Several acres of woods surrounded the complex; they’d been set aside for development that had stalled for years. The rest of the city was booming, a college town turned trendy city after the recent economic upturn. New buildings were going up every day, microbreweries and dog parks and tattoo-parlor-sandwich-shops, but where we lived was still untouched. There was a murky retention pond visible from the balcony of our unit, where small black turtles sunned themselves on rocks. The woods surrounded the pond, and we could hear coyotes howl on hot summer nights.

Once, a few weeks after we’d moved in together, we went to Blind Tiger’s. The bar was known for having been a speakeasy during Prohibition, before the college even opened, when the town was still a small shipping port. It had a pool table with plywood on it, which after midnight people often stood on and danced, and an old photo booth that produced grainy black-and-white photo strips. My roommate hated this bar—she preferred a slightly classier college bar that boasted a popular wine night—but I loved it.

When we were three drinks deep and toying with the idea of dancing, we saw a group of guys who had also gone to our college. I only vaguely recognized some of them, but my roommate seemed to know exactly who they were. Her demeanor changed, face hardening. The highlight of sweat along her cheekbone glowed.

“Stacey’s friends,” she mumbled. At this point, she and Stacey had newly been seeing each other, and she’d only recently discovered that he wasn’t single after seeing a social media photo of his engagement dinner celebration. The boys at the bar were probably in that photo, though they were indiscernible to me.

I nodded at the toad, and felt that after this night, no harm could come to me.

She left to use the bathroom, and I waited at the bar, sipping my vodka cranberry. One of the guys—I recognized him from a freshman year class, was it Kyle? Ben?—approached me.

“You know that girl?” He gestured to the direction she’d walked off in.

“You live with her?” he said. His friends around him laughed like crows. Then, earnestly, as if it were a reasonable thing to say: “She’s an untrustworthy whore, you know. Going after Stacey.”

I threw my drink in his face. The cranberry stained his white shirt pink. He jerked backward and shoved me in response, probably on instinct, and I drunkenly fell sideways. My face scraped against the corner edge of the table, which was serrated with peeling plastic. “What the fuck,” I said, my voice coming out oddly flat, like a robot’s.

The bouncer kicked us both out, like we’d come together, and then we had to awkwardly walk through the gravel parking lot. He tried to speak to me, but I just shook my head and tuned him out until he walked in the opposite direction.

My roommate came outside. Her makeup was smeared in the corners of her eyes, black smudges of eyeliner now extending to her temples. She sat down next to me on a parking bumper at the edge of a willow tree.

“You really didn’t have to do that,” she said.

I could feel blood congealing alongside my left eye, but I didn’t touch it. I heard a croak and looked down at my shoe. A small brown toad was there, looking up at me with round eyes. I thought perhaps he could have been a relative of Our Friend; the woods surrounding the bar led to the same ones that surrounded our condo. Why had I so immediately jumped to the defense of my roommate? She was becoming my best friend, I realized, even though I hadn’t consciously chosen it. I nodded at the toad, and felt that after this night, no harm could come to me.

I wandered into the kitchen, my hair wrapped in a towel and my feet still wet from the shower. There in front of the cabinets stood the plumber. He wasn’t even plumbing. He was just standing there in overalls, staring at the Post-it notes and magnets on the fridge.

He gestured to the area where the sink had flooded, to the waterlogged towels that lay haphazardly on the floor.

“You really fucked it up,” he said. “Gonna need a whole new sink.”

“Did you tell the landlord that?”

“That you need a new sink? Yeah.”

He paused. “I just said to him that it needed to be replaced. Didn’t say nothing about the glass in the drain.”

“I’m going to put on some clothes, but help yourself to a beer from the fridge,” I said.

I combed my hair, blow-dried it, and put on a pair of olive-green cloth overalls that I privately called my “sexy without trying” outfit. Meanwhile, I could hear the grunts and sighs of the plumber as he labored away at the glass-filled garbage disposal. He spent upwards of an hour fixing the sink, kneeling in the sour-smelling water that had flooded around his legs. I lay in bed in the other room, fondling my labia absently.

I wasn’t turned on by the plumber—instead, I was thinking about something my roommate had told me about Stacey. She was tight-lipped about him now, since she knew I didn’t approve, but when they’d first started seeing each other, she’d come home one winter evening red-cheeked and wine-drunk. She told me that he had requested something of her during foreplay. He had asked her, “Who do you wish I was?” When she told him, he closed his eyes and his face grew blank. He asked her all about the person’s mannerisms, and then he did an uncannily accurate impression, as though possessed by the spirit of another. It was the best sex of her life, she told me breathily.

“I’m all done,” the plumber called.

I removed my hands from my crotch and wiped them on the side of my overalls. I was feeling strangely ripe and sensual. There must have been something going on with the moon.

“Your outfit kinda reminds me of Luigi from Mario Brothers,” he said when I walked into the kitchen.

“I think it’s more like Yoshi.”

“The froggy thing?” He laughed and cartoonishly wiped sweat from his brow. “Did you say you had beer?”

I handed him a bottle from the fridge. We sat down together on the balcony, looking out on the retention pond. That day it was green and silty, reflecting the clouds above.

It turned out the plumber’s name was Pual. It was pronounced like the ordinary biblical name Paul, but there had been a typo on his birth certificate. He didn’t drink the beer I gave him. He just swished it around in the glass.

“My buddy works in construction,” Pual said. “They’re starting work on clearing out and leveling these woods next week. Putting up a whole bunch of condo units and a storefront, too.”

“Yeah, and the storefront is going to be made of repurposed shipping containers.”

I took a sip of beer. “Why? Wouldn’t that look like shit?”

“’Cause it’s cheap. In the cargo industry, those things have a lifespan of only a few years before they get too banged up and can’t be used. I guess the developers are going for the urban repurposed look.”

“Like the Barge.” Downtown, there was a new cocktail bar that had opened on a floating barge (it was aptly named). It had pop-up streetwear vendors and late-night DJs who spun real vinyl. There was always a line out the door, and if you got sick from too many martinis, it was easy to throw up over the side directly into the river. I had gone there only once, with my roommate one night after Stacey had committed some injustice against her. We danced and drank in the way only scorned young women can.

Pual shrugged. “This whole town’s gone crazy. Everyone wants to live here now.”

I often had the sensation that I was standing just outside of a door to a party, unsure of whether I should open it.

I looked out at the woods and tried to imagine them replaced with a series of cheaply built rentals, parking lots, and mangy dogs on leashes. A stream of bubbles emerged from the retention pond, likely the resident alligator I suspected we harbored. In an hour, the sun would sink and the cicadas would start up their choir. The land was swampy, the kind of soil that your shoes sink into, and littered with ticks and vines and all kinds of snakes. It was no place for people—that much was true—but from my balcony above, I liked to hear it, to know it was there, a parallel universe governed by the frogs that sang for no one but themselves.

One week later and I heard no coyotes, even though it was June. Pual was right—a construction truck had appeared on the dirt service road that cleaved through the woods. It had a smiling cartoon man in a hard hat on the side of it, which I knew to be a bad omen. Neither my roommate nor I had seen Our Friend in several nights. We were concerned he had died, been squished by a car or carried off by one of the red-tailed hawks that circled above us.

In between her job interviews, I complained to my roommate on the balcony about the new construction. She was formatting her résumé while I smoked a clove. I didn’t even like those things, but they made me feel earthy.

“Once they build up this area, they’re sure to raise the rent,” I said, after a long-winded rant about the differences between marsh, swamp, and bog.

She looked up at me, startled. “You think?”

“Yeah. Pual said the rent is going up all across town because of the construction in the swamplands. There’s like, growing industry here or something.”

“Our plumber.” I flicked ash from the clove into a broken seashell. “We need to call Robert. He’ll know what’s going on.”

We did not call him, of course. Doing so would have broken our mutual code to never acknowledge the other’s possible humanity.

My roommate stood up and shook her hair out. It glinted in the sun, a result of the streaks she’d had her hairdresser put in, and I understood for the first time the value of such a service. “I gotta go. I have an interview in fifteen.”

I didn’t want her to leave. Smoking a clove alone was an entirely different act than doing it in the presence of others. Around someone else, it said, I’m a fun and quirky hippie! Alone, it said, I probably have a serious addiction to the simple physical act of inhaling smoke. “What job are you applying for?” I asked her.

“A product manager at a bank.”

“Oh,” I said. “So, what would you do?”

She laughed. “I guess I’d manage product.”

Twenty-three was a reasonable time to get a real job, I supposed. I often had the sensation that I was standing just outside of a door to a party, unsure of whether I should open it. As the minutes went by, the party got louder and drunker, and more and more people came and opened the door. “After you,” I kept saying to them, gesturing. “After you.” They went in, but I stayed, listening, watching through the frosted windows, and the longer I waited, the harder it got to just reach out my hand and open the door. “Twenty-three is the same vibe as nineteen,” my roommate had said once, abstractly. I knew what she meant.

Soften Up, 2020, oil on canvas by Coady Brown. Courtesy the artist and Nazarian / Curcio

Despite advancing to the final interview, my roommate did not get the job. They chose someone who was more pleasant, perkier and brunette. “I read a study once that people perceive brunettes as more trustworthy,” she said. She cried briefly, then shook out her tears, took a long shower, and washed her hair, coating it in some exotic oil that made it shine. I hid my relief through nonchalance.

We were on a budget due to our lack of real jobs, so we didn’t go out to drink that night the way we usually would in response to the rejection. Instead, we finished the leftover vodka on our pantry shelf and mixed it with the juice of several grapefruits that were about to go bad. My roommate tied her hair up in a bun and threw an assortment of ingredients into the silver margarita shaker her aunt had gifted her when she graduated high school. She liked to play hostess: liked to cook, make cocktails, create elaborate cheese and salami spreads, even just for the two of us.

After three of these concoctions it seemed of the utmost importance that we go down to the grass and then woods by the pond and look for Our Friend and the frogs. We could still hear some of them, the chorus croaking on, though their numbers had clearly dwindled. It was the quieter part of a symphony, I told myself, the sad part before the finale when everything becomes loud again.

By the murk of the water, the song of the frogs became clearer. I heard their ribbiting and hopping over the dewy grass. Small black turtles sank into the water when they heard us approach. We were giggling and leaning on each other, recognizing the absurdity of the moment. All the animals were still here, the moon was still the same moon above us, the woods were still the same woods, I told myself. It would be okay.

A frog hopped onto my bare foot above my sandal, gummy and fidgety. In a panic, I flicked my foot so the frog flew off. It made a bizarre noise as it flew.

“What was that?” my roommate asked.

“Did it get dizzy or something?”

We spent the next ten minutes testing our theory by picking up frogs and spinning them around a few times. Then we’d gently set them back down on the grass and listen to them as they hopped away, disoriented. The ribbits had morphed into a distorted waaaaa-ooooh, waaaaa-ooooh. We laughed at the sounds until we cried. We laughed until we peed a little bit in our pants. We left the woods and lay on the grass, feeling the investigatory poking of bugs at our backs.

I glanced over at my roommate to see her face bereft of the grin she’d worn moments before. She had become sad, suddenly, the way alcohol often made her. Years later, she would announce her sobriety on her social media page. I would find out one morning, scrolling through my feed, and respect for her would fill into my chest like a liquid.

“I want my real life to begin,” she said.

“Isn’t this real life?” I asked her.

She smiled. Her eyes glittered with tears. The whites of them shone under the silver of the moon. I wanted to reach out to her, but I didn’t.

We lay there until the bugs had chewed a ring of red dots onto our skin. We decided to crawl our way back to the condo, lather ourselves in anti-itch cream, and escape into the television together. A wilderness survival reality show was on, and we spent the next two hours discussing what we would do differently if we were contestants. Of course, we overrated our shelter-building abilities and our general outdoorsmanship, but we were certain that if given the chance, we could weave a really good fishing net.

Eight days later, a message came from Robert in the form of an email.

I am writing to tell you of important news Due to a variety of factors the rent for your unit will be increasing by five hundred dollars when the lease renews next month There are many new amenities and developments happening in this area and the complex has become more lucrative for investors This is in consideration of the fact that rent has been the same for ten years while cost of maintenance has been rising Please direct any questions to me Thank you Robert

“It sounds like he’s thanking himself,” I said. We were sitting together on my bed, reading and re-reading the email.

My roommate sneered. “Yeah, Robert! Thanks for making this place unlivable!” I had never seen her be truly spiteful before. She was always so pleasant and proper, even when she talked to the people from the electric company on the phone about overcharging us. But now that our inertia was threatened, there was a cascade of anger from her.

“We can find another place to live,” I ventured.

“I’m researching where I can buy cockroach eggs to plant in the condo as we speak.” She tapped away at her phone.

“We could still live together, even if we move,” I said. But she’d wandered into the kitchen already, distracted. I stared at the ceiling. The beige popcorn coating stared back at me. We had only been here for a year, but it felt like I’d given birth to three children in it, painted its walls and cleaned its baseboards, broken its sink with the glass shards and then built it back up again.

My roommate wandered down the hall. “Stacey says he wants to talk,” she said, her eyes still glued to her phone. “Fuck. Do you think he’s breaking up with me?”

In the distance, a lone coyote howled. “You have too much love to give,” I said.

“I’ve got to go and see him,” she said. “The German cockroach eggs will be here in three to five business days.”

The door slammed behind her and I heard her hurried footsteps down the wooden stairs, the quick scream of her car’s belts as she pulled away. When the sun sank into a muted, hazy yolk, I took a beer from the fridge and walked down the stairs. I sat on the bottom step, waiting for Our Friend to come out. As if nothing had gone wrong, as if there were no bulldozer coming to these woods and no alien landlord screwing us over, he emerged on cue. I could have cried when I saw him. The toad stood there, staring at the wall, thinking things I couldn’t possibly understand. Occasionally, he let out a high-pitched croak that was swallowed by the chorus of the crickets.

As I listened, my thoughts were spiraling. What if I was wrong? What if Stacey really did leave his fiancée in order to be with my roommate, and what if she moved in with him? I pictured her donning a beekeeper’s net as if a veil, her hands covered in golden honey that he drizzled all over her naked body. She’d get a different job as a product manager, and so she would manage the product of money, handling neatly folded stacks of cash as they moved in and out of the bank on golden serving trays. The trays of money would go on those wheeled carts that servers roll in fancy restaurants, and then they would roll away from me, picking up speed, growing farther and farther away, while I, running toward them, grew exhausted and slowed down.

I was surprised to feel wetness on my cheeks. I didn’t feel the throat-choking snot that usually comes with tears. It felt placid, a silent cry, like in a movie. I probably looked pretty crying like this, but there was no one around to see.

“Come on,” I said to the toad in front of me. “Please. Tell me what to do with my life.”

Our Friend looked at me. His throat quivered a little, bulged slightly outward then back in. If there ever were a moment for him to speak to me, it was now. But he said nothing, of course. He was only a toad. His eyes looked in two different directions, one east, one west. After a long moment, he hopped away.

Just after midnight, my roommate came home and her face was streaked with charcoal-colored tears. I poured her a glass of Boone’s Farm and put on Superbad, her favorite movie. I held her on the couch while the waning chorus of the frogs croaked on. The door was opening, we had to walk through it. We only had so much time before the outside world closed in on us.