Photograph by Kendrick Brinson

Jazze Pha and Cee-Lo Green’s Lost Album

Revisiting the never-released “Happy Hour” LP

By Michael A. Gonzales

It was after 11:00 P.M. on a Saturday night in the fall of 2005, and Jazze Pha and Cee-Lo had just performed at a Baton Rouge nightclub. Riding on a long stretch of lonely highway, these two soul bros were barnstorming through the South promoting their upcoming album-length collaboration, Happy Hour. “I’ve had to turn down a few production jobs [while working on Happy Hour], but it’s been worth the sacrifice,” Jazze said, talking to me on his manager’s cell phone. “When it comes to music, me and Cee-Lo are kindred souls.”

The rap magazine XXL had assigned me to write a story about Happy Hour. Having spent a considerable amount of time in Atlanta covering the r&b and hip-hop scenes in the ’90s, I’d met both men before, and was disappointed that this wasn’t an in-person interview. Still, I made the most of my phone call with the duo, who were in their tour bus returning home after a gig.

In 2005, Jazze and Cee-Lo were celebrated residents of Atlanta contributing to the soundtrack of the city. Pha was the discoverer and primary producer of then-teen star Ciara, also known as “The Princess of Crunk & B,” and whose triple-platinum 2004 debut Goodies was one of the more popular (and bestselling) albums of the new millennium. Meanwhile, Cee-Lo’s work with the Goodie Mob and the Organized Noize family, which included OutKast, Joi, and Cool Breeze, was critically acclaimed.

“Me and Cee-Lo both grew up fans of different kinds of funk and soul,” Jazze said. In the background of the bus, I could hear loud conversations and PlayStation noise. “So, when we decided to work together, we knew the songs had to have that kind of sweet mack daddy appeal that we loved so much.” Jazze passed the phone to Cee-Lo.

“Let me say I’m very proud of the Happy Hour project, because, although it is quite entertaining, me and Jazze were also trying to create tracks that would broaden the musical horizons of the listeners,” Cee-Lo explained. “You know, incorporating our own inner visions with what folks want to hear in the clubs and on the radio.” Indeed, it sounded as though the duo had mixed a recipe for aural success—Happy Hour was slated to be released by Capitol Records a few months after our conversation.

As with most urban projects in the aughts, early copies of albums and mixtapes were sent to various music critics and magazine writers. I was living in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn that year, and I remember blaring the Happy Hour advance at party-over-here levels. My two favorite tracks were the mid-tempo joint “Enjoy Yourself” and “Man of the Hour,” a gangsta-slick song that sounded like it could’ve been a blaxploitation film’s theme music.

“That project just felt like such a perfect partnership,” music journalist Amy Linden recalled. “Both artists had a tangible place in hip-hop and r&b—it just felt like a winner.” However, after putting in the work, including marketing the title track as a single and video, Capitol pushed the release date back. The album was delayed a few more times, until it was ultimately never released.

In the history of music there are many shelved projects that could’ve been classics: Jimi Hendrix’s Black Gold suite, Joi Gilliam’s Amoeba Cleansing Syndrome, Marvin Gaye’s Love Man, Dr. Dre’s Detox. In 2006, Happy Hour joined the pantheon of unreleased discs that might’ve been cultural contenders. Happy Hour made an impression on me as a fan of both artists and the soul music they made that has lasted since 2005. My advance CD disappeared years ago, but damn near two decades later, whenever I spin the leaked version—which is up on YouTube at the time of this writing—I’m struck by the “what if” possibilities, in terms of influence and legacy, that might’ve spawned from the project had it been given a proper release.

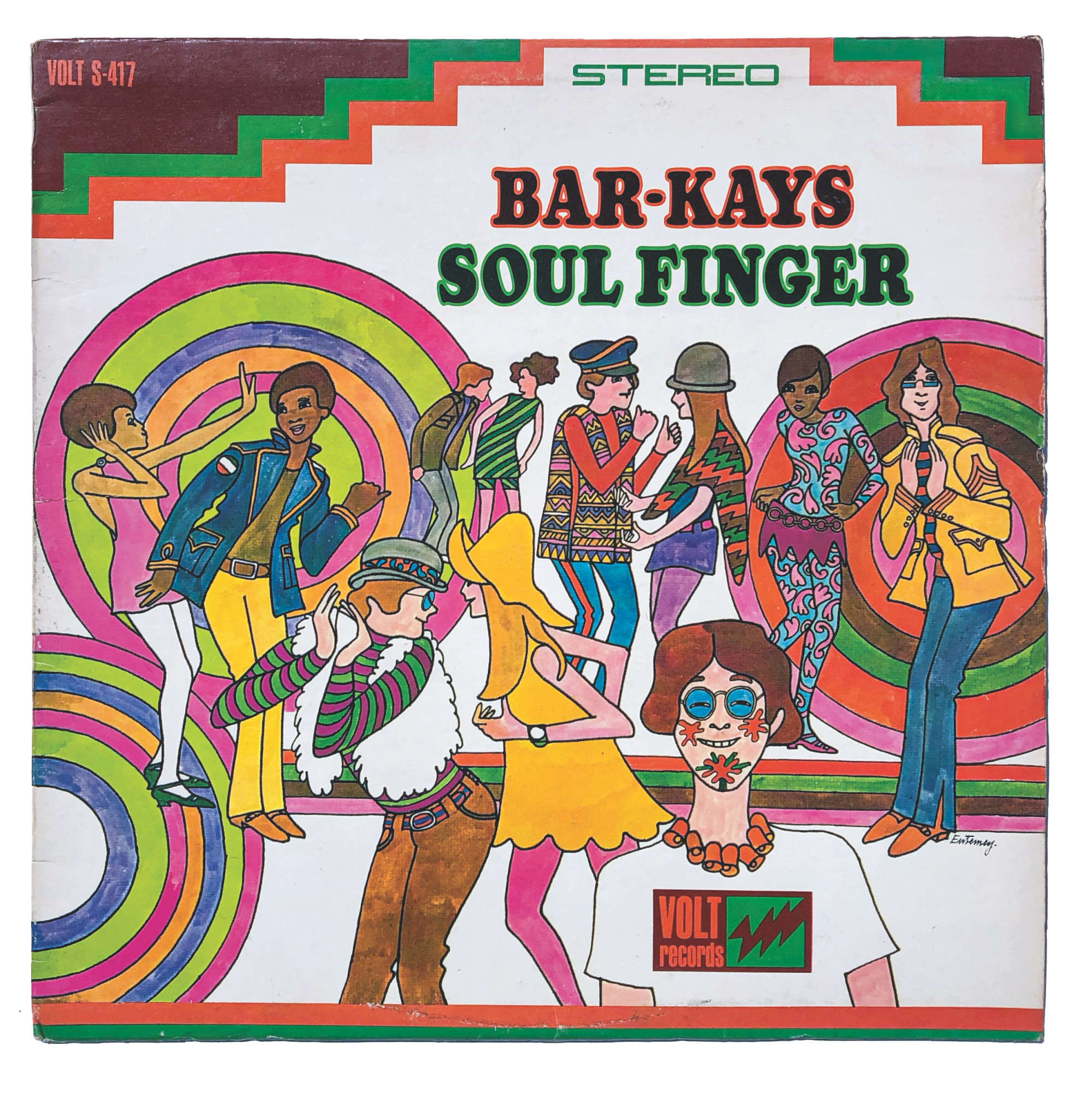

Jazze Pha met Cee-Lo in 1996, when they were both twenty-two and Jazze had recently moved to Atlanta from his hometown of Memphis, Tennessee. The son of Bar-Kays bassist and Stax Records star James Alexander, Jazze’s government name is Phalon Alexander. He was named after his father’s friend and Bar-Kays saxophonist Phalon Jones, who was eighteen years old when he died along with most of the original band in the tragic 1967 plane crash that also killed soul master Otis Redding.

The Bar-Kays were recent high school graduates who had released their first single, “Soul Finger,” just eight months before the plane went down in the icy waters of Lake Monona. Since there wasn’t room for Alexander, who was only seventeen, he had been booked on a commercial flight. Trumpeter Ben Cauley was the only survivor of the crash. Alexander was given the brutal job of identifying the bodies.

“With considerable determination James Alexander and Ben Cauley didn’t let the name of the Bar-Kays die in the plane wreck,” British journalist Tony Cummings wrote in Black Music magazine in 1974. “They formed a new group. Ronnie Gordon was the first organist but he was soon replaced by Winston Stewart. Similarly, Vernon Smith took over from guitarist Michael Toles after a short spell, while the new drummer was Roy Cunningham, brother of the deceased Carl.” (Cauley left in 1971 but continued to play on sessions for Candi Staton, Gregg Allman, and B. B. King.) The new band was dynamic both in the studio and on stage, as they proved in the 1973 concert film Wattstax, which featured the Bar-Kays performing their own material as well as backing up former mentor Isaac Hayes, who they’d accompanied on classic discs Hot Buttered Soul (1969) and the Academy Award–winning Shaft (1971).

A year after the Wattstax release, Phalon Anton Alexander was born, on April 15, 1974. “He [Alexander] had a great effect on me,” Jazze Pha told Memphis Flyer in 2013. “Not only was he my dad, but I really was a fan of [the Bar-Kays’] music, and a lot of the people that were around them… I just think of great lineage. A great foundation that they built for young folks as a reference to go back and see what the real music sounds like and go back and see what a real performance looks like, and what real imaging is. They were their own individuals. They weren’t like anybody else.”

Jazze’s mother Denise was a former session singer. Because of her maiden name of Williams, Jazze explained to me over the phone in 2005, interviewers often ask if his mom is the classic r&b singer Deniece Williams, who sang ’80s anthem “Let’s Hear it For the Boy.” Years later, Jazze described his mother as “a background wizard” who provided vocals on albums by Barbra Streisand, GAP Band, Earth, Wind & Fire, and D. J. Rogers.

His parents separated when Phalon was a boy, and Williams moved with her son to Los Angeles. During the summer months, he went on the road with his pops and met his father’s funky contemporaries: Cameo, Luther Vandross, the Jacksons, among others. Jazze’s most vivid memory of this period is the night he met a purple-clad man. “I got the biggest thrill when my father introduced me to Prince,” he said. “I was just a little kid who was supposed to be in bed, but my father let me go to an after-party just to meet him. It was the night the Bar-Kays opened for the Time, and Prince walked into the room with Morris Day and Jerome. I remember he was wearing purple pajamas.”

Back home, his mom tried to be stricter. “Against my mother’s wishes, the first record I bought with my own money was Parliament’s Motor Booty Affair,” Jazze said, laughing. “I loved that song ‘Aquaboogie,’ but I had to hide the record between my mattress, so she wouldn’t find it.” Yet once the school bell rang, it was all about being cool. “Anybody that knows about Memphis knows that it’s a real player city,” Jazze said. “I grew up around a lot of older cats, but where I come from even the little kids listened to P-Funk, Isaac Hayes, and Curtis Mayfield while daydreaming what color Cadillac they were going to buy when they got older.”

Jazze’s own music career started early with Coast to Coast, an aspiring hip-hop duo he formed with his younger brother Derek. In 1990, he transformed himself into a young new-jack-swing-styled singer/rapper and signed as a solo artist to Elektra Records. Modeling himself after Bobby Brown, Jazze co-produced his debut Rising to the Top, which he recorded under the name Phalon in Memphis at Kiva Studios. Once owned by the Bar-Kays, the Rayner Street sound lab also hosted sessions with Stax star Rufus Thomas and soul-stirrer Solomon Burke.

“Since he was a boy I tried to teach him the foundation of Black music, and the production lessons he learned at Kiva Studios were his training ground for what came next,” James Alexander told me over the phone in 2024. “He watched me, the engineers, and the whole process.” Alexander also taught his son to be courteous even when giving orders: “You don’t have to be imposing to get your ideas across.”

Rising to the Top didn’t sell well, and Phalon was soon dropped from Elektra Records. Meanwhile, 384 miles away, there was a musical revolution bubbling. In the 1980s, Atlanta had become the adoptive home of soul/funk pioneer Curtis Mayfield and Cameo leader Larry Blackmon. By the early ’90s, some of the hottest artists in the country (TLC, Kriss Kross, OutKast, Toni Braxton) and producers (Babyface, Dallas Austin, Jermaine Dupri, Daryl Simmons) were operating from there as well. Music industry folks were jetting down to ATL on the regular, hoping to soak up some of that flavor for their own projects.

“Whatever you’re trying to do, you have to take it to the tenth power to be successful,” Jazze once told Memphis Flyer, explaining the thinking behind his 1996 move to Atlanta. “It’s the Hollywood of the South, and I wanted to pursue my dream,” he said. “I would’ve gone anywhere to do it.”

Jazze soon began producing singles with LSG (“Let a Playa Get His Freak On”), T.I. (“Chooz U”), Ludacris (“Keep It on the Hush”), and Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes (“Jenny”). In 2003, Jazze produced the funk bop “Bowtie” for OutKast’s instant classic Speakerboxxx/The Love Below. It was on these songs that Jazze began refining the soulful but laidback sound that would define his production style. Of course he could bring the high-energy grooves, as heard on Ciara’s Goodies. But Jazze wasn’t afraid to show his smooth side.

While Jazze perfected his sound, Cee-Lo continued to work with Goodie Mob and released two avant-soul/neo-funk solo albums, Cee-Lo Green and His Perfect Imperfections (2002) and Cee-Lo Green…Is The Soul Machine (2004). Although both discs appealed to his hardcore fans on the eclectic side, sales were low, and he was soon dropped from Arista Records. Though Cee-Lo publicly viewed himself as a “free agent,” to an industry that judges by an artist’s platinum success, his future looked bleak.

Jazze and Cee-Lo connected again when they worked together on Cee-Lo Green…Is the Soul Machine. “Jazze did a song called ‘The One,’ and it was from that experience I knew we would work well together,” Cee-Lo told me in 2005. The track, which Jazze co-wrote and produced, is built around a bounce beat and also features guest-rapper T.I. “Last year, we bumped into each other at the Miami Airport and he asked me to join him in the studio. After that first night, it was on.”

Cee-Lo Green (left) and Jazze Pha (right). Photograph © Mark Mann/AUGUST

H appy Hour succeeded in capturing the essence of a smoky bar, the kind of place where people blared the jukebox while talking smack and slurping drinks. Recorded in a mere month at Atlanta’s famed Patchwerk Studios, the album was a sonic celebration, a dazzling display of grooves perfect for both dancefloor strobe lights and bedroom red lights. “When we started working [on the project] I was recently divorced, so I had the luxury to let it all hang out and be as wild as I wanted to be,” Cee-Lo told me in 2005, laughing. Listening to his funky-fresh Rick James homage “Disco Bitch,” which featured the velveteen purrs of the Pussycat Dolls, it was obvious that he had no problem letting his freak flag fly.

As Jazze and Lo’s album’s name indicated, Happy Hour had a “grown & sexy” groove, a quality that was becoming acceptable (and desirable) as the 1990s era of hip-hop kids began to mature. On the title track, Jazze perfectly blended cool r&b and a funky rap bassline with a mature swagger. Lyrically, the song served as an anthem to hardworking nine-to-five women looking for a good time and a cocktail—“Apple martinis, cosmopolitans, piña coladas…”—before they went home.

“It sort of reminded me of [Kool and the Gang’s] ‘Ladies Night,’” Cee-Lo said in the press materials. The song got a blinged-out video directed by Fat Cats, the same cinematic duo who had done clips for Ciara’s “Oh” and T.I.’s “Bring ’Em Out.” Shot in a fancy nightclub and released in September 2005, the clip featured slick cars, beautiful extras, and tailored suits, plus cameos from Mannie Fresh and Ciara.

In 2005, Richie Abbott was the senior director of publicity at Capitol Records in Los Angeles, where he worked closely with Jazze and Cee-Lo and loved every minute of it. “Capitol went into a full swing campaign,” the West Coast publicist told me recently. “I flew the guys out to the East Coast where we set-up cocktail bars in some editorial offices and served drinks while playing the album.”

Happy Hour’s multifaceted vibe gave Jazze the opportunity to work with more artists he admired. A potent cocktail of ’70s disco, ’80s new jack swing, and, of course, hip-hop, the project featured guest appearances from Keith Sweat, Mannie Fresh, Aaron Hall, and more. “They did a song [“Enjoy Yourself”] with Nate Dogg that I thought could’ve been a huge single,” Abbot told me. “Enjoy Yourself” is danceable, but cool—the kind of soul jam you can boogie to without breaking a sweat.

“Working with Cee-Lo is like working with my favorite brother,” Jazze Pha told Billboard in November 2005, a few weeks before the album was supposed to be released. “We shared so many of the same interests already that once it got to the music it was like second nature. You’re looking at a perfect match.”

Soul Finger by the Bar-Kays. Photograph by Carter/Reddy

By the spring of 2006, with Happy Hour still sitting unreleased, Cee-Lo had joined forces with producer Danger Mouse (Brian Joseph Burton) and released the brilliant track “Crazy” under the name Gnarls Barkley. The first single from the duo’s debut album St. Elsewhere, “Crazy” became a megahit, won a Grammy, and made Cee-Lo a bigger star in the eyes and ears of the world. In the November 11, 2006, issue of Billboard, Jazze Pha confirmed that he and Lo had finished twenty songs, but that the album wouldn’t be completed until the rapper/singer came off the Gnarls Barkley tour.

However, even after Cee-Lo’s newly acquired “Crazy” fame, Capitol neglected to release Happy Hour. “Everybody at Capitol was excited by the success of ‘Crazy,’ and the plan was to build off of that,” Richie Abbott remembered. “I don’t recall there being an official company meeting about shelving the project, but suddenly so much time went by and there was no still no Happy Hour.”

In the nineteen years since the project wasn’t released, it has been a “best of times, worst of times” scenario for Cee-Lo. From 2011 to 2013 he was a judge on The Voice. In 2012 he was accused of rape (the charges were dismissed due to lack of evidence). In 2014 he was convicted on drug charges. In 2020 he released the Dan Auerbach (Black Keys)–produced album CeeLo Green Is Thomas Callaway.

Jazze Pha is currently working with gospel artists Jevon Dewand and the Trap Starz. Having been involved in church life and listening to gospel artists like the Clark Sisters and Andraé Crouch since he was a kid, Pha’s genre shift is a return to roots. As he told one interviewer, “Even when I started rapping as a youngin’ I would integrate those [gospel] melodies in my music.”

For years I thought I was the only one who mourned the shelved status of Happy Hour—until Jared Boyd, a columnist at the Daily Memphian, included the project on his 2017 list “25 Southern hip-hop albums that should have been classics.” Boyd wrote, “Where those two projects [Cee-Lo Green and His Perfect Imperfections and Cee-Lo Green…Is The Soul Machine] are avant-garde, this one felt prime for the party. At the helm of production, Jazze Pha is arguably hip-hop’s purest soul man… His signature production style is the basis for the album’s single, as well as leaked tracks that have floated around the Internet. It’s hard to say ‘what could have been,’ but I’m willing to go out on the limb in saying this collaborative album would’ve shattered expectations.”

Without a doubt, I agree. It feels bittersweet now to revisit that 2005 conversation, during which Jazze and Cee-Lo’s creative energy and excitement were palpable. “Like the albums I listened to when I was younger, Happy Hour is about something more than the music,” Jazze said. “Hopefully, what me and Cee-Lo have created will become a movement.”

This story was published in the print edition as “Last Call.” Subscribe to the Oxford American with our year-end, limited-time deal here. Buy the issue this article appears in here: print and digital.