Mae Glover’s Songs and Hoodoo

The eminence gris of Beale Street

By Cynthia Shearer

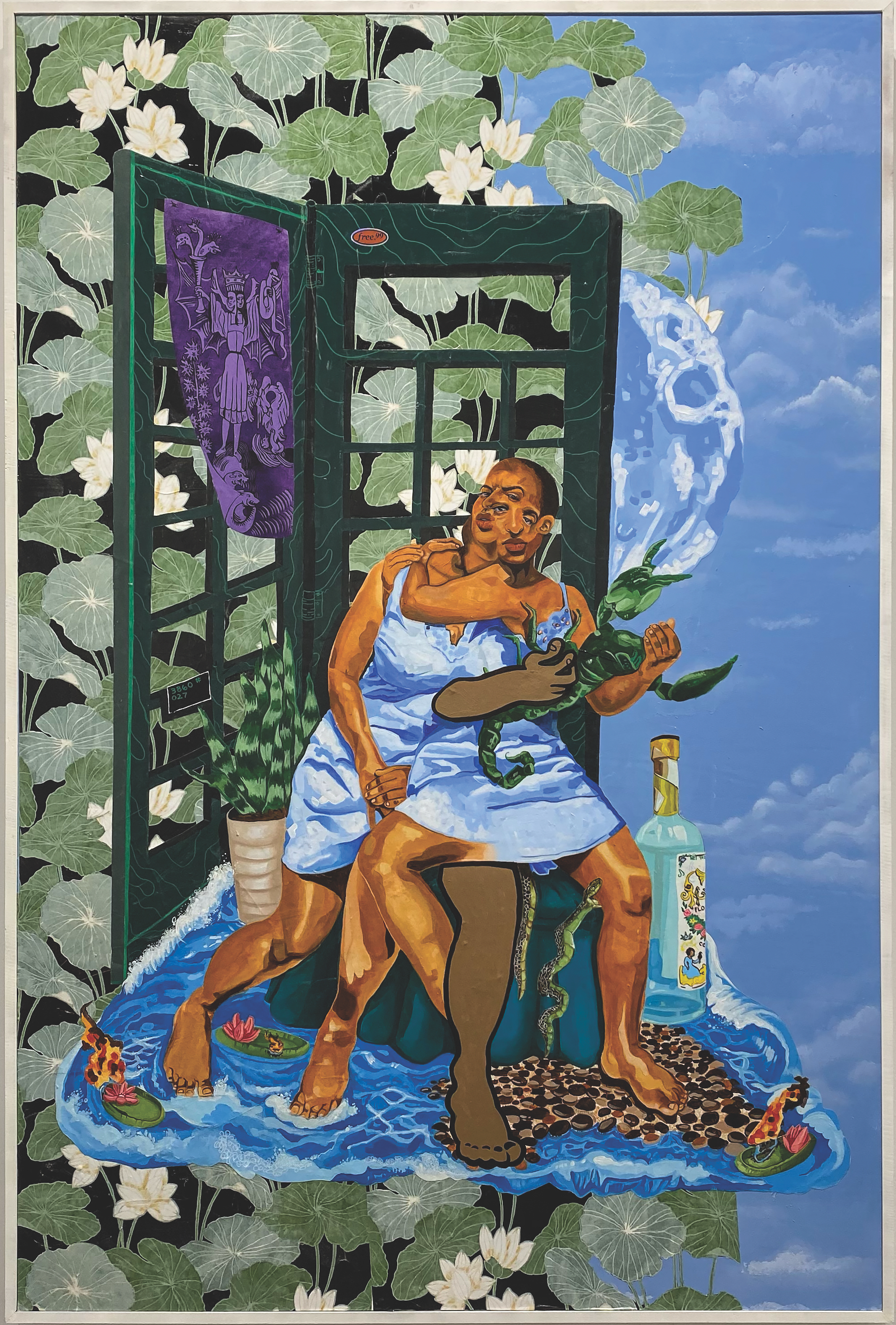

Scorpion & Frog, 2021, acrylic and Polytab on panel by Ahmad George

Once upon some decades ago, Memphis was the confluence of two holy rivers, one made of muddy water and the other made of Black souls in transit. Many were musicians passing through on the way to opportunities elsewhere; some decided to stay. By the 1920s, the song lines emanating from Beale Street clubs both gave voice to the distinctive forces that shaped them and laid the foundation for popular music over the next hundred years:

“If it keeps on rainin’, levee going to break”

“Well, I lost my money at the Jim Kinane”

“I’m going to send you a ticket, hoping you will come”

“They ’rest me for murder, I ain’t harmed no man”

“The judge decreed it, the clerk he wrote it”

“I’m going to Memphis, stop on Fourth and Beale”

“Good mornin’ little schoolgirl”

“Mr. Crump don’t ’low no easy riders here”

Among the arrivistes in 1928, twenty-year-old Lillie Mae Hardison, at that time a performer affiliated with the Nina Benson Traveling Medicine Show. She met her husband, Willie Glover, and took his name. Soon Mae Glover’s voice became part of the early Memphis blues mix along with Gus Cannon, Furry Lewis, Memphis Minnie, and many others whose lyrics often alluded to hoodoo. Gus Cannon’s jug band sang about Aunt Caroline Dye, one of the most trusted and powerful hoodoo practitioners in America, who lived just off the Rock Island Line in Newport, Arkansas. She was the “gypsy” in W. C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues.” Memphis Minnie may have been thinking of her when she sang, “Hoodoo Lady, you can turn water into wine; I’ve been wondering, where you been all this time?” In Black Magic, religion professor Yvonne Chireau offers, “The blues were the first commercially produced music to explicitly embrace the culture from which conjuring traditions emerged.”

Mae Glover’s first recording, “Joe Boy Blues,” will make you wonder what she knew about hoodoo. The song has the stately gait of a Ma Rainey country blues, but it’s about second sight, about extrapolating meaning from a sign, thereby being able to foresee the loss of a man’s love.

I had a dream last night; it’s got me worried in mind.

I was crossing muddy water, and that is sure a bad sign.

For anybody interested in the divination of dreams, the song still resonates almost a hundred years later, whether your hoodoo of choice derives from the African ancestors, the Old Testament prophets of the Mediterranean, or a Viennese gent named Freud.

Mae Glover cut twenty-two songs on various labels between 1927 and 1931, using various names. Her recorded oeuvre shows the range and professionalism of someone fluent in both downhome and vaudeville blues, but her recording history drops off abruptly after 1931. Where did she go, we might wonder, seeing that curtailment in the discography?

Fast-forward fifty-odd years, to one winter night in Memphis in the early 1980s, when African American literary scholar Hortense Spillers was back in her hometown for the holidays. At Blues Alley, she took in the performance of a woman of advanced years wearing a knitted cap and singing old-school blues. The singer was an eminence gris on Beale, tough as a barnacle in a neighborhood where the less tenacious had been swept away by a tide of precarity and “urban renewal.” Patrons called her “Ma Rainey.” At first Spillers assumed she was the real one. She later learned the Memphis woman’s true identity while reviewing Sandra Lieb’s 1983 biography of Gertrude Pridgett, the original Ma Rainey. In seeing Glover performing as “Ma Rainey No. 2”, Spillers had felt the presence of a “visible structure of cultural descent,” an avatar of some force larger than either original or duplicate: “It is as though the name was never exclusively the subject’s, but the property of a culture, specifically, the culture of the Mississippi Delta, in tireless patterns of rebirth and renewal.”

There’s a story here. We will likely never know the whole of it, but her presence in Memphis is marvelous to consider.

“H

oodoo has endured numerous definitions,” writes Katrina Hazzard-Donald, a dance scholar whose erudite interdisciplinary study Mojo Workin’ documents the sacred side of hoodoo and offsets a long tradition of white demonization of it. She says that hoodoo is the “reorganized remnants” of ancestral West African spiritual belief systems such as Bambara, Yoruba, and Bakongo. What we have left are fragments that survived the efforts of white enslavers to eradicate them. One of hoodoo’s surviving precepts is that we inhabit two worlds simultaneously, the visible physical one and the invisible spirit one. Human malady can issue from the spirit world. Events in the visible world can be adjudicated through formal consultation with a practitioner whose methodology might include the use of symbolic images, objects, and substances, as well as music, incantations, and dance. Hazzard-Donald has called for contemporary researchers to delve deeper into the impact of hoodoo on African American cultural life, especially the protection of health. “The blues is full of references to Hoodoo, root work, conjuring, and fixing of enemies, rivals, mates, potential mates, and situations,” she states, “but we must have more than a simple documenting of Hoodoo references as found in blues lyrics.”

Here’s an outsider’s definition of hoodoo, from Harry Middleton Hyatt, an American white man so hoodooed by hoodoo itself, he was compelled to systematically interview 1,605 African American informants and one white one in the 1930s, on the subject of hoodoo. After this somewhat quixotic exercise of interviewing informants who may have taken oaths to keep hoodoo safe by keeping it secret, he cannily offered this: “To catch a spirit, or to protect your spirit against the catching, or to release your caught spirit—this is the complete theory and practice of hoodoo.”

That sounds mighty like the blues.

If you ask, blues practitioners will often define blues as a feeling rather than just a fixed twelve-bar form. “It’s not just about bad times. It’s about the healing spirit,” contemporary bluesman Taj Mahal has said. “Blues is a deep sentiment that all of humanity has. It doesn’t matter where you come from, when you hear that sound, if you’re alive, if you are a real person and you don’t have all these false walls up around you, you’re going to feel that.”

“See, the blues was borned in me,” Mae Glover said. She made her debut as Lillie Mae Hardison in the U.S. Census in 1910 at the age of two, listed with her father Campbell Hardison and her mother Nancy along with older siblings in Columbia, Tennessee. Cam was a “laborer” in the census, but also a Sanctified preacher who moved the family to Nashville. By 1920 Mae’s mother had died. At thirteen, she ran away with the Tom Simpson Traveling Medicine Show, wherein a man named Jim Hayden showed her the ropes, including how to mix products they sold as medicines.

So Mae’s early life offered two possible points of contact with hoodoo: the Sanctified church and the floating demimonde of traveling medicine shows already entering their slow death rattle phase with the advent of 78 rpm records and radio. Her résumé included the Bronze Mannequins, Georgia Minstrels, Harlem in Havana, and Vampin’ Babies, as well as F. S. Wolcott’s Rabbit Foot Minstrels—Ma Rainey’s former outfit.

Mae first crossed paths with the fabled “Mother of the Blues” Gertrude Pridgett at the Frolic Theater in Birmingham, Alabama. She said:

Now she was hard. Her people, she couldn’t get along with her people. She drank, and you know quite naturally when you drink, you don’t do so well with your people….I was wild about her. She had me doing a whole lot of her songs.…She stayed high so I’d have to do her songs.…She wouldn’t be feelin’ bad or nothing, she’d just go on and let me sing.

Glover’s role may have transcended that of an understudy; her adoption of the “Ma Rainey” name could indicate an apprenticeship to a master artist, a vital connection and transfer of gift of the sort Julio Finn writes about in The Bluesman: The Musical Heritage of Black Men and Women in the Americas. Blues and hoodoo are sacred at the same time they are secular, says Finn, despite being viewed as “devil’s music” in Glover’s time. This can manifest as an initiation like the assumption of a second name, as when McKinley Morganfield became Muddy Waters. A new name is more than a marketing stratagem; it can be a necessary consecration or a claim to a lineage.

In perennial Beale Street lore, “Ma Rainey No. 2” carried a pistol, sometimes dressed like a man, engaged in fisticuffs, bar-hopped with Bessie Smith, and may have been the “Madame Glover” who ordered her hoodoo supplies in person at Schwab’s. Census reports show her always close to Beale, renting rooms on Fourth Street and Gayoso, a widow working as a “maid” in offices or private residences. The 1940 census lists two Lillie Mae Glovers inhabiting an apartment at 113 Fourth Street. One occupant is male, the other female.

“I ruled that street between Fourth and Hernando,” the Los Angeles Times quoted her in its obituary in 1985.

A lot of what we know about Glover’s hoodoo life comes from an interview with Margaret McKee and Fred Chisenhall, Memphis Press-Scimitar journalists who interviewed her in 1974. If she had been one of Harry Middleton Hyatt’s anonymous informants interviewed in the nearby Eureka Hotel in Memphis in the late 1930s, she didn’t mention it. On that occasion she asserted that hoodoo was just “junk” and told funny stories about unnamed clients who had consulted her about man trouble. One wanted her man to leave, the other wanted her man to come back. Solutions to each would require the gentlemen’s socks. When the clients brought clean socks, she had them procure dirty ones; otherwise, the fix would be futile.

Even if Glover called herself a charlatan, she may have known some authentic Black Belt hoodoo from a time before it was commodified—her insistence on dirty socks recalling the foot-track magic of Yoruba and Bakongo belief systems. According to Michael Edward Bell’s 500-page dissertation on Hyatt’s hoodoo files, dead skin and other foot-sole detritus were prized as “primary products,” ranking right up there with nail parings or hair. “Sympathetic magic” is the anthropological term for this: The practitioner manipulates an object or material once closely associated with the target, and then symbolically suggests a fate for the target. Mae Glover instructed the client who needed to rid herself of an abusive man to throw his dirty socks into a creek: “And just like the water take away that sock, the spell is gonna take away that man.” Mae Glover’s everyday household hoodoo could have offered troubled clients a sophisticated formal opportunity to embrace closure or to express a wish, during which she served as officiant and witness. To those who would object to her practices as “primitive” because they were not empirically proven, it’s helpful to recall that neither were Freud’s.

Mae Glover’s early recordings are available via Document Records in Mae Glover: Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order 1927–1931 (DOCD-5185). In these twenty-two songs, a young newcomer to Beale Street surveyed the toll that diaspora, Jim Crow, and the Great Depression were taking on relationships between Black men and women. She assumed an advisory stance on the perennial human cycles of loving and leaving. For someone so young, she had some sharp counsel on offer.

In “Don’t Beg Your Man Back,” Glover offered a strikingly modern warning about stress management:

We don’t have to worry if our men treats us right.

Just don’t give a doggone if he stays out both day and night.

Women that have the blues are just hurtin’ themselves,

And if they keep it up, death’ll be knockin’ at their door.

“Skeeter Blues” and “Shake It Daddy” are risqué but restrained, so they pale in comparison to works by Trixie Smith, Lucille Hegamin, or other queens of the double entendre of that era. “Gas Man Blues,” performed with John Byrd, is a comic vaudeville sketch in which a resourceful woman in arrears with her payment barters her body: “Mr. Gas Man, please call ’round here after dark.”

Beale Street, Memphis, TN, 1940 © Southern Stock Photo/Alamy

“The County Farm Blues” is Glover’s rendition of “Chain Gang Blues” by Ma Rainey. This lyric presents a Black woman’s point of view of being imprisoned during the Jim Crow iteration of the American carceral state. Glover’s narrator is doing time because her man could not pay her bond. “Hoboken Prison Blues” amplifies that theme, asking, “Mercy, mercy, mercy, where can mercy be?”

One of Glover’s most interesting recordings is “Forty-four Blues/Big Gun Blues.” Glover was the first woman to record it, noted by the English blues don Paul Oliver in his 1958 book Screening the Blues. The “Forty-four” referred to an Illinois Central train that ran along the levees parallel to the Mississippi. Its whistle could trigger thoughts of leaving in a lover. In 1929, a piano virtuoso named Roosevelt Sykes from Arkansas rehabbed it to include a “Forty-four Special” Smith and Wesson revolver: “Lord, I walked all night long, with my Forty-four in my hand; I was lookin’ for my woman, found her with another man.”

Two years later, Mae Glover flipped the song to a woman’s point of view, removed the image of the gun, and bent the song back to the equanimity of some earlier versions. The only trigger is the Illinois Central train whistle:

Now, baby, when you get loaded, think that you want to go.

You ain’t no better, baby, than the sweet man I had before.

Some of these mornings, daddy, and it won’t be long

You gonna look for your mama; baby, I’m going to be gone.

“The blues woman is the priestess or prophet of the people,” liberation theologist James Cone writes. “She verbalizes the emotions for herself and the audience, articulating the stresses and strains of human relationships.”

There is more to learn about Glover’s late-period Blues Alley performances and her seven-year gig at the rough and white Cotton Club in West Memphis. Though that work was an important income stream for her, we can only conjecture how wide her influence was, evening by evening conjuring up an aperture into a different era, year after year. Who are we to say Mae Glover was not a priestess or a prophet? We have no empirical proof she was not. Those evenings could have been for some white audiences the first contact with the synaptic magic of a live African American blues performance, even if they would never encounter that Yoruban word, ase, life force. Whether your own holy river of choice is history or hip-hop or psychoanalysis, we live in two worlds at once, the one we can see and the one we can’t.

This story was published in the print edition as “The Eminence Gris of Beale Street.” Subscribe to the Oxford American with our year-end, limited-time deal here. Buy the issue this article appears in here: print and digital.