Memphis Funk’s Second Life Overseas

Ebonee Webb was big in Japan

By Jared Boyd

Disco Otomisan by Ebonee Webb. Photograph by Carter/Reddy

In the waning days of 1975, following years of social tensions and economic peril, federal marshals enacted a near-violent takeover of Stax Records’ headquarters in Memphis. The physical coup that spelled the company’s foreclosure marked the bitter end of a soul music titan—one that had not only shaped radio and onstage success, but also pioneered the Black avant-garde and even delivered an Oscar-winning movie theme. Decades later, speculation lingers about whether lenders, along with record industry executives, conspired to stifle the growing sociopolitical influence of African American musicians who had risen from poverty. Whether or not there was a coordinated effort, Stax’s collapse incapacitated the local music industry, as its dominance had sustained Memphis’s studios, theaters, mastering labs, and rehearsal halls.

For every veteran musician left wondering what was next after Stax’s collapse, countless other hopefuls were searching for where to begin. Among them were the young bands following in the footsteps of lauded Stax luminaries the Bar-Kays—groups that embraced a new wave of funk by prioritizing syncopated grooves, stylized vocals, and outlandish visuals rather than the smooth harmonies of the previous decade. Lineups formed and re-formed, vying for attention and strategizing toward a breakout moment. In 1973, a then unknown group called Con Funk Shun left their gig as a backup road rhythm section for Stax’s rising stars, the Soul Children, to make a name for themselves. A new group stood in position to support the Soul Children on the road: a collective of youngsters named Ebony Web. The group had started as the Del-Rays in the halls of George Washington Carver High School, situated in South Memphis, not far from where Stax Records planted its flag in what would come to be known as “Soulsville, U.S.A.” However, it was nearby rival Royal Studios and its soul music architect, Willie Mitchell, who gave the teenagers their first shot at recording. Founding members—guitarist Willie McClain, drummer Curtis Steel, and bassist Ray Griffin—filled out the Del-Rays’ lineup with a revolving door of young musicians, including vocalist Charles Liggins and keyboardist Perry Michael Allen, already an apprentice under Mitchell, before recording their first sessions. After discovering a similarly named group in the marketplace, Mitchell insisted on a name change, prompting the band members to mint Ebony Web.

The teenage core of the group had already conquered much of the city’s night scene, packing out hole-in-the-wall event halls and playing grander stages like Beale Street’s historic 5,000-seater the Hippodrome. “I had to get parental permission to play because I was about sixteen, still in school,” Griffin remembers. “We all had to stay in the dressing room when we finished the gig.” But recording in the studio with Mitchell, the producer who’d recently made a star of Al Green on Hi Records, felt like higher stakes.

“Knowing I was with the group, I became less nervous because we’d been together so long.” Griffin adds, “Someone of the caliber of Willie Mitchell, who was kinda hot at the time, being interested in us was exciting.”

The musical encounter was also uncharted territory for Mitchell. His signature sound had yet to flirt with the stretched-out psychedelia that the group hinted at on tracks like “The Time of Me,” penned by Perry Michael Allen. Mitchell was eager to work with the group, but the label’s promotion side proved less enthusiastic. “At the time, Hi couldn’t handle that kind of stuff,” Allen says. “But Willie gave it a shot. He was never closed-minded. But the office let it go with no push or nothin’.”

Seemingly as a compromise, the group recorded “I’ll Still Be Loving You” in a style resembling the signature Hi Records sound made famous by the likes of Green, Ann Peebles, and Syl Johnson: centered around a sparse, lush rhythmic base with warm, robust accented horns. They even cut a rendition of the Temptations’ “The Way You Do The Things You Do” in 1972 before departing the label the following year. That’s when they made the jump to Stax, although Allen would stay behind with Mitchell.

Only a couple of years later, the seismic demise of Stax left Ebony Web without a home once again. Griffin ceded the group’s leadership to focus on becoming a session player. That vocation proved prolific for him, as his bass guitar lays the foundation for ubiquitous hits such as Bobby Bland’s “Members Only,” Z. Z. Hill’s “Down Home Blues,” and Anita Ward’s “Ring My Bell,” to name a few. But headliner recognition for Ebony Web still seemed out of reach.

“I didn’t have the insight on how to make the group more popular than it was at the time,” Griffin says. “We were successful locally. But everyone wanted to be national, be worldwide.”

In fact, they’d already made an impression globally in support of Rufus Thomas in 1977. After a short tour with the showman in Africa, the band made an even more significant splash while accompanying the singer in Japan.

“[Japan] fell in love with us and brought us back a couple of times. We ended up playing at the Mugen, the number-one disco club in the world,” says Charles Liggins.

A rejuvenated version of the group signed with management and forged a new direction, promoting Liggins to lead vocalist, setting their sights on capturing the growing appetite for Black music abroad. They even debuted with a revamped name, warping the letters into a more striking Ebonee Webb.

“I first met the group at the end of last year when they came to Japan as the backing band for Rufus Thomas,” reads the rough translation of liner notes included in the album jacket for Ebonee Webb’s first full-length LP Disco Otomisan, released in 1978 on Seven Seas, a subsidiary of Japanese juggernaut King Records.

“They were performing at Mugen in Akasaka and quickly became a hot topic, gaining popularity among disco people,” the notes continue. Their writer was Ueda Ka, an arranger who takes credit for introducing the band to the staff that would produce Disco Otomisan. Further into the notes, Ueda expresses uncertainty that the collaborators’ language barrier could be overcome, considering that the traveling musicians mostly didn’t read music. But after distributing charts for a cover of Stevie Wonder’s 1966 single “A Place in the Sun,” he found his pretensions undone at the hands of the seasoned funksters’ undeniable, organic instinct for the source material.

“Why did this happen? Of course, it was because the song was by Stevie Wonder and was much more familiar to them,” Ueda writes of the cover tune, which showcased the band’s new vocalist and pianist Patricia Henderson.

“However, what they realized for the first time through this rehearsal was that for them, who cannot read music, it is much easier to understand the arranger’s intentions through the arranger’s own piano playing in the same rehearsal room as them, in other words, through the raw music itself, than by being handed a single impersonal piece of paper. Moreover, it directly strengthens the degree of communication between them as people in a common musical circle.”

“We learned the language [eventually], because there were at least five or six times that we flew over. [At one point], we were there as often as we were at home,” Liggins says. The demand for the group’s music was high among Japanese listeners. “It was hard for us to go to the fast-food places to get anything to eat because we gathered a following and a crowd anywhere we went.”

Soon, the group recorded a second album for Seven Seas titled Memphis Soul Meets Japanese Folk Songs. Soaked in the sort of funky sophistication then associated with the likes of Earth, Wind & Fire or Weather Report, the album makes good on its very straightforward billing. Across its eight tracks, the band not only flexes their musical ability, but also delivers linguistically, performing Japanese lyricism over a disco-jazz bed. A cover of the Niigata Prefecture folk song “Sado Okesa,” featured on this magazine’s companion LP, showcases that versatility. Ebonee Webb pairs what otherwise might’ve been a schmaltzy soprano saxophone solo in the song’s opening with a resounding harmonic vocal workout. By the climax of the composition, a symphony of rhythm guitar and dreamlike keyboards fuses together, forming an uncanny blend of synthetic and organic sound.

Ebonee Webb would eventually be routinely greeted in Japan by several other Memphis funk bands of their generation, acts who’d previously battled with them back home for the coveted number-two spot behind the heralded Bar-Kays.

“There were a lot of Memphis bands back and forth to Japan,” says Ekpe Abioto, formerly Peter Lee of Galaxy, a rival group signed to Arista Records in their heyday. “We would overlap at clubs like Mugen or the Bottom Line in Osaka. Some of us would be leavin’, and somebody else would be comin’. Straight out of Memphis, but we got to see each other on an international level.”

Abioto remembers admiring the growth of Ebonee Webb’s repertoire after their departure from stages back home, noting that even the male vocalists in the group would perform a compelling version of “Lady Marmalade.”

“They were one of the tightest show bands you ever wanted to see anywhere, and they could play any kind of music,” Abioto says. “They were a top band: I’d rank them with the Bar-Kays, Con Funk Shun, or any of them. We looked up to them.”

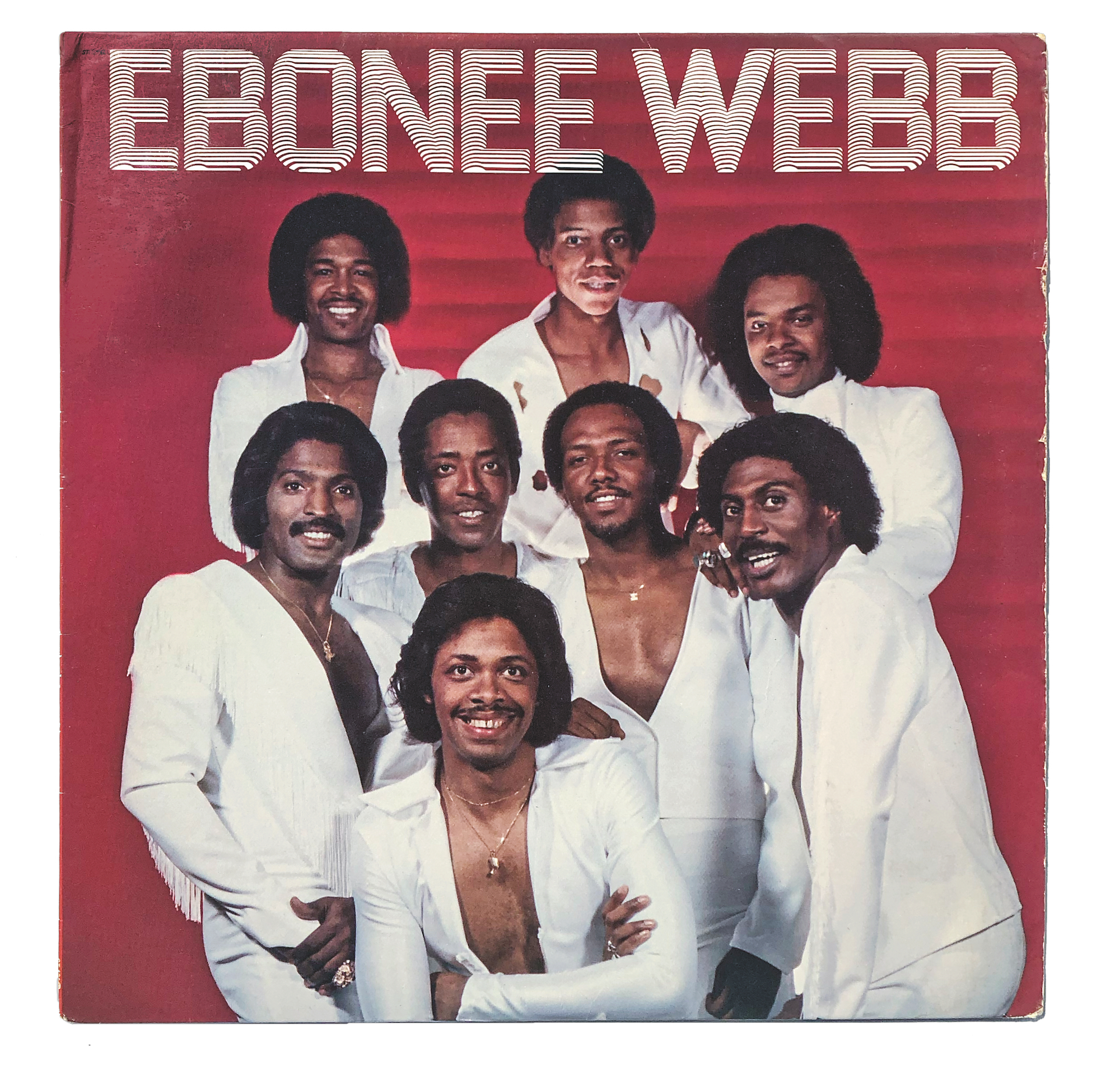

Ebonee Webb’s self-titled album. Photograph by Carter/Reddy

Coincidentally, the Bar-Kays had taken notice. Memphis’s reigning funk authority found more success with a new label home at Mercury Records. In 1978, they managed two competing chart hits: “Shine,” on Mercury Records, and Fantasy Records issue “Holy Ghost,” an infectious demo recording that had been left behind in the final days of Stax Records. With two new albums on two separate labels, each boasting an otherworldly sound previously unfamiliar to fans of soul music from the South, the band’s leadership was courted to build a production house. Kays’ manager Allen Jones, at the helm of Unisound Productions, snatched up Ebonee Webb and secured a deal with Capitol Records for the group’s first LP to be released domestically.

Jones is widely credited with shifting the image of the Bar-Kays, who initially fashioned themselves as a junior version of the drastically more reserved Booker T. & the MG’s. In the same vein, he goaded Ebonee Webb into the hypersexual, Afrofuturist androgyny that was commonplace in the Black music cosmosphere of the approaching 1980s. On looks alone, Jones and the Bar-Kays preceded Prince, Rick James, and the many more to come.

“We took on a flashy look like the rockers of the time,” Liggins says, “but we still played funk and r&b. That was our makeup, our sound.”

Another change was the ascendance of saxophonist Michael “Chico” Winston to lead vocalist, as his falsetto was suited for the genre-bending finesse popular with the glam crowd. His high register stood out on singles that employed kick drums and deep, driving, post-disco bass licks, like “Something About You” and “Anybody Wanna Dance.” Besides, the sound of soul music was beginning to abandon hornwork altogether, favoring brand name synthesizers like Moog, Oberheim, and ARP.

Keyboardist Andrew Jackson says he’d long admired Ebonee Webb before being invited to audition for their traveling road band. Supporting the group’s second LP on Capitol, 1983’s Too Hot, Jackson was treated to the perks of being in a popular band touring Japan in the 1980s. “The Roland Juno-60 had just come out,” he remembers. “I bought it in Japan and brought it back to the States. I know it was the only one in the city at that time because I was getting booked for session work just so people could hear its sound.”

That trip to Japan, after the release of Too Hot, would prove to be the group’s last.

“We were going pretty strong when we came back from Japan,” Liggins says. “We had a lot of ideas about the direction we wanted to take the group in, but we weren’t making a lot of money at the time.”

Jackson says the band was looking to make another leap, leaning deeper into their rock influences, even asking management to tap the white engineers in Memphis who’d already recorded the likes of Big Star and ZZ Top, often in the same studios.

“Our production company wasn’t havin’ it,” Liggins says of the residual power struggle.

The pecking order was well in place. Jackson and Liggins say Ebonee Webb was asked to fall in line with other acts on the Unisound roster, along with an increasing number of local funk contemporaries garnering major-label attention. Con Funk Shun became darlings on Mercury, and groups like Xavion, Sho-Nuff, and Brothers Unlimited brought up the rear.

“I think that, on the surface, everybody really respected one another and were very intrigued by the gifts and talents of the other band,” Jackson says. “But everybody was vying for that spot under the Bar-Kays, for a chance to be number two. That was the unspoken part of the competition.”

Ultimately, the popularity of club DJs in the Memphis circuit may have been the competitor none of the rival bands saw coming, with hip-hop soon on the rise behind it. With attitudes and behaviors changing, the same nightclubs that were once brutal battlegrounds for funk groups maintained their weekly crowds while promoters cut costs by employing radio personalities and turntable jocks to turn the party out. In the process, bandstands emptied across the city’s night scene.

Disillusioned with their production company and unwilling to take on the costs of going at a third LP as an independent venture, Ebonee Webb disbanded.

“You know, I thought Ebonee Webb would make it big,” says Melvin Jones, a popular DJ of the time on Memphis’s WLOK and later Magic 101, the local radio property at the frontlines of the rapid transition from funk to disco and hip-hop. “The record company has got to be in your corner to break you nationwide. You have to be exceptional to make it without a major push from a record company.”

“We never had a big enough record to take us to Soul Train,” Liggins says of the group that captivated both Memphis and Japan. “But our records did take us all over the world. And we had a hell of a ride.”

Ebonee Webb’s “佐渡おけさ (Sado Okesa)” is Track 6 on the Memphis Music Issue LP. Click here for full song credits and liner notes.

This story was published in the print edition as “Big in Japan.” Subscribe to the Oxford American with our year-end, limited-time here. Buy the issue this article appears in here: print and digital.