The Life, Death, and Memphis Blues of Jay Reatard

Remembering a punk visionary and the songs he left behind

By Andria Lisle

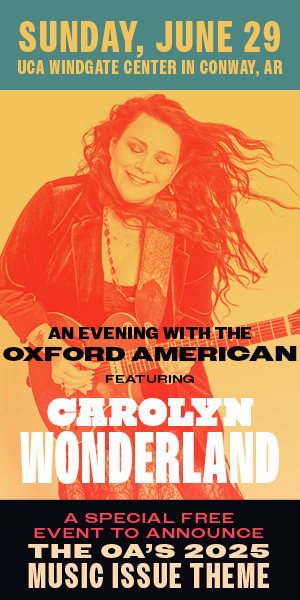

Jay Reatard in Memphis, TN, 2006. Photograph by Dan Ball. Courtesy the artist

In the fifteen years I knew Jay Lindsey, I could have filled a book with the beautiful and terrible things he did, or was said to have done. He experimented with everything—music, sex, drugs. He was ruthless and mean, a lover of women and a hater of them. Generous to a fault, but cold whenever it suited him. Brilliant, careful, yet prone to wild and reckless acts. He created with precision, but lived with chaos. He feared being belittled, but no one cut him down quicker than himself. I think of Jay almost every day. I miss the mayhem, the humor, the drive that pushed him forward until his heart stopped one night. My memories of him could fill an ocean. His absence grows heavier as time passes. Who would he have become? How would he have changed?

Some nights, I sleep well, knowing that Jay is at rest. His grave, a few feet from Isaac Hayes’s plot in East Memphis’s Memorial Park cemetery, has frequent visitors. I drop by every so often and note the guitar picks neatly laid at the edge of his marker, which says JIMMY LEE LINDSEY JR. AKA JAY REATARD at the top and MEMPHIS PUNK ROCKER at the bottom. On other nights, I lie awake, staring at the ceiling, wrapped in regret and loneliness. I’ve lost too many friends—to drugs, booze, disease, bad decisions. I don’t know what to make of heaven, the afterlife, or whether we go on in some way. We’re all going to die, but Jay’s death was too soon, too spectacular. Often, it haunts me.

By the time I crossed paths with Jay, I’d attended thousands of punk rock shows. He was born, in my opinion, a decade too late. Scenes had come and gone, and by 1995, the year I met Jay, local bands had splintered into multiple camps: garage rock, gutter punk, and indie, with a rainbow of variations in between. From my perch behind the counter of Shangri-la Records, the Midtown Memphis record shop, I saw—and heard—it all. I loved some bands, hated others, and was bored by much of it. So I had to laugh that spring when a broad-shouldered fourteen-year-old with a shaved head burst into the shop to buy an issue of MAXIMUMROCKNROLL, the bastion of DIY punk rock that had, in my opinion, long outlasted its usefulness.

I remember the incident, not for Jay, who resembled any Memphis kid who had scratched beneath the surface of grunge, but because of what came next. I watched as he thumbed through a few album bins, then stopped in front of the magazine rack. The door swung open again, and in came a large woman, Shelley Winters in a muumuu, swinging a big purse like a rolling pin looking for its mark. Later on, I’d come to know her as Devonna May, Jay’s mom. She aimed at the kid, but he slipped the punch like a professional. While she hollered a litany of threats, he nonchalantly ambled to the register where I sat, taking it all in. There was no dignity in any of it, but he kept his head high. In a show of support and some secondhand embarrassment, I refused to acknowledge her presence. The scene repeated ad infinitum that year.

Jay’s early life was marked by trauma—though its full extent remains obscured. What is certain is that he transformed his pain into music, using creativity as a means to escape poverty and as an attempt, mostly unsuccessful, to heal personal wounds. His drive was fueled by the belief that a better life was always within reach. In Jay’s case, it appeared to lie, aptly, just inside the door of Shangri-la, which was in a repurposed bungalow a few miles northwest of his childhood home on Dunn Avenue. Opportunity came via Devonna, who seemed to willingly drive Jay to Shangri-la, only to yank him out by his ear minutes later. Regardless, within weeks of that first visit, Jay had built a network of friends who could, and would, offer a lifeline.

Jay Reatard in Kassel, Germany, 1999. Photograph by Pete Jay

Jay’s first friend, as far as I know, was a lanky brunet kid named Jonathan Boyd, another Shangri-la regular who called the record store an “audiotopia” for disenfranchised youth. Jonathan was in eighth grade with Jay at White Station Middle School, where the two formed an intuitive connection centered on music: specifically, the Memphis band the Oblivians and their first full-length album, Soul Food, a hot seller at Shangri-la in 1995. Years later, Jay and I discussed his discovery of Soul Food during a formal interview, conducted amid the press run for Watch Me Fall, his final album.

“Everyone had been telling me that if I wanted to play guitar, I needed to listen to the Ramones,” Jay told me. “I bought a copy of Ramones Mania on CD, but it sounded too together, too intimidating, and too professional. I heard the Oblivians, and they sounded drunk and out-of-tune. The first thought that went through my head was, wow—this is completely achievable! I can do this!”

It’s easy to imagine Jay in his bedroom on Dunn, gleaning clues from the record collection he had begun to assemble. Like the rest of the properties on the block, Jay’s home was a small, squat, working-class residence that, more often than not, had the shades drawn, plastic covering gaps in the small windows. Built in the 1940s, it was purely utilitarian, designed for efficiency rather than pretension. It was just one of the eighteen houses Jay lived in between the ages of eight and sixteen. The Lindseys—Jay; his father, a roofer named Jimmy Lee Lindsey Sr.; his mother; and his two older sisters—had moved to Memphis from Lilbourn, Missouri, in 1988. A few years later, when Jay was eleven, his parents divorced. Devonna had suffered from postpartum depression, and from Jay’s account, he and his sisters mostly raised themselves. His discovery of underground music, specifically the blues-informed din made by local punks like the Oblivians, marked a turning point.

“I wouldn’t have known about the majority of music I later got into if it hadn’t been for a Rolling Stone interview with Kurt Cobain,” Jay said. “He talked about Black Flag and the Meat Puppets. It’s weird how, even though I started listening to that stuff, my biggest musical influence was right in my backyard.”

I wasn’t there when Jay invited Jonathan out to his dad’s house, a suburban ranch-style home tucked into a street lined with broken-down campers and rusted-out pickup trucks. Even so, I can picture the scene: two boys, one wiry and bookish, wielding a black Fender guitar, and the other sturdy and energetic, bent over an overturned bucket on the bedroom floor.

“It’s a vivid memory, because it was astonishing to witness,” Jonathan says. “I remember sitting on the carpet in that little house and watching him pound away on that bucket, very earnestly recording material.” I picture Jay fiddling with his tape deck and a tiny microphone, trying to filter out the noise from the living room where his stepmother sat chain-smoking and watching game shows. “I was embarrassed because I didn’t have the confidence to play with him or write songs together,” Jonathan says. “He had such an intense drive and focus to make something, and he took himself so seriously at fifteen years old.”

Left to right: Stephen Pope, Billy Hayes, and Jay Reatard in Oakland, CA, 2008. Photograph by Chris Anderson. Courtesy the artist

Within weeks, a fan letter Jay mailed across town to the Oblivians led to a more assertive music partner: Greg Cartwright, aka Greg Oblivian, who was twenty-three at the time.

“I picked up Jay from his mom’s house and we hung out for an afternoon,” Greg remembers. “At fifteen, I’d thought I was pretty into music, but he was even more so than me. He was having a hard time; he didn’t seem to have many friends. When a fifteen-year-old is looking to adults for guidance, it tells you something about the adults in his life at the time. Although musically, Jay was sharpened to a very fine point, he was having a hard time adjusting to the world.”

Jay was reserved at that first meet-up, but the crucial outlet that music provided for the emotions roiling through his nervous system was undeniable. While the older Oblivians saw their band as somewhat of a punk parody, Jay was viscerally experiencing disillusionment and rebellion. Like all of us who encountered Jay early on, Greg quickly ascertained that he was the real deal. “Give that ugly, most deranged part of yourself a microphone, then turn around and see how ridiculous it is,” Greg says. “It was a part of me I was revisiting and reexamining, but Jay was in it. He was still figuring out what he was singing about, but he wasn’t playing around. He had the skill to construct songs and lyrics. He already had his own kind of voice, which had an earnestness that told me that something deep was going on with him.”

Zac Ives was a twenty-year-old student at Rhodes College when he met Jay at a show that same year. The two exchanged phone numbers, and, says Zac, “the next time there was a band playing, I got a call asking if we could pick him up. Jay was fifteen, doing things like getting into fights with his mom and getting kicked out of the house. I remember picking him up one day and seeing his crap all over the lawn. He told me he’d busted his guitar through the wall. The next week, he’d have a song that recounted his story.”

“When I’m mad, I’ll break anything / ’Cause I don’t give a fuck about anything,” Jay howled on an early recording. “Oh this time I went too far, I did / I picked up a motherfucking guitar / I busted in a big ass hole in the wall / Why did the police have to get called?”

“You could watch it happen in real time,” Zac marvels. “He was coming from a place of pure angst and adolescence.”

By mid-autumn 1996, Jay had lost interest in school. He was still at home, although life under Devonna’s roof was fraught. Already a provocateur, he began to preemptively call himself a “Reatard” before anyone else had the chance. He also dubbed his first band the Reatards, long before he’d recruited other members. He added an ‘a’ to the name because, he later told me, “the Oblivians had an ‘a’ in their name, and I liked how it looked. It’s aesthetically better.”

That October, shortly before Jay left home for good, he mailed a Reatards demo to me at Shangri-la. Recorded in his bedroom with Greg on a four-track cassette recorder, these early works mined the Oblivians’ lo-fi, garage punk sound, with a brattiness that was wholly and utterly Jay. The production quality was rough and amateurish, which added to its appeal. Jay’s songs mimicked the Oblivians while also eclipsing them in power and sheer emotion. His talent for crafting memorable hooks was already in full effect, as was his take-no-prisoners vocal style—a furious, nasal tenor that was simultaneously abrasive and remarkably on key.

From my first listen, Jay’s demo tape managed to straddle the timeline of punk rock itself, beginning with Iggy and the Stooges’ 1973 album Raw Power and running right up to the contemporary indie punk band Lil Bunnies; he may have stumbled across a CD or a 7-inch by the latter at Shangri-la, who knows. Thanks again to the Oblivians, Jay demonstrated a healthy interest in Memphis music history. He included three “blues” numbers on that first cassette and reprised one, “Chuck Taylor Blues,” on the second tape he mailed me, which was memorably titled Fuck Elvis, Here’s the Reatards. He covered Fear and the Beatles, and he had the nerve to rip off a song I co-wrote with Eric Friedl, aka Eric Oblivian, called “Jim Cole.” The lyrics of our version, which we wrote about a friend of ours who worked at Sun Studio, went, “Jim Cole’s got too much soul / I can’t stand it.” Jay’s take was Nietzschean by comparison: “You took away my soul / Now I ain’t got nowhere to go,” he snarls over a heavy riff and a makeshift rhythm track. Jay was pounding a pickle bucket, and I was blown away.

The seriousness with which he assembled the packaging of that first tape tickled me. Jay was, by all accounts including his own, a poor student who was on his third attempt to pass eighth grade. Yet he’d done his rock & roll homework and included a hand-drawn cassette cover, an insert with songwriting credits, and a typewritten press sheet for which he interviewed himself. WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE BEVERAGE, Jay asked. THAT’S A STUPID QUESTION, Jay answered, BUT IT’S PINK LEMONADE SNAPPLE.

When I mention that interview to Greg, he laughs. “In Jay’s mind, he’s already arrived: he’s got interviews, shows, recording sessions. He’s simply filling in the blank space as a fantasy. He was so driven that he already saw himself at that next level.” With a bucket, a mic, and a barely functioning four-track recorder, Jay had soaked up what made the Oblivians great and sculpted it into his own form of self-expression. Even though we were half a generation older than him, we were all jolted awake by his singular ambition.

“For me, making music was important,” Greg tells me. “But for Jay it was an absolute necessity.”

When school started back up after the Christmas holiday, Jay was a no-show. “He’d stopped coming regularly, and eventually, he disappeared,” Jonathan says. After leaving home, Jay tried to move in with Greg, who was a father with a young son of his own. He then crashed at Zac’s house, before eventually moving in with Alicja Trout, a Memphis College of Art student who was already understood as a fiercely individual figure in the Memphis music scene.

“When I met Jay, he was living at home,” Alicja says. “There was a little buzz, probably from the Oblivians, about this kid who plays rock & roll and plays drums on a bucket. From then on, he was just around, a member of the crew of musicians around Midtown. Then he told me he was trying to get out of his house.”

At the time, Alicja was in her early twenties. She had just ended a long-term relationship with Jack Yarber, aka Jack Oblivian. “I said, ‘Well, I have an extra room,’ and I made Jay a pallet on the floor,” she remembers. “After he had lived with me for a while, I made him get a job. At the time, he was just my roommate. I wouldn’t have considered dating him. After four years with Jack, I wanted to be independent. And because of Jay’s age, he wasn’t on my radar, even though he was dating friends of mine. Eventually, our relationship turned into something more.”

I have no idea how Devonna felt about Jay moving out. She would call me at Shangri-la if too much time had passed without hearing from him. She called the rest of us too. You tell my Jay to call home, she’d cajole. Sometimes she sounded more threatening, echoing the words of the truancy officers who regularly dropped by her home.

By the end of 1998, Eric Friedl had released two Reatards records on his label, Goner Records. The first was an EP titled Get Real Stupid, which Jay described as “punk-n-roll from Memphis [with] songs about ramen noodles, Chuck Taylors, getting laughed at, and soul, which this record has lots of.” The second record was a frantic, rage-filled full-length called Teenage Hate. By now, Jay had recruited Ryan Rousseau and Steve Albundy to form a trio—another nod to the Oblivians, also a three-piece band—that pounded through a diverse array of covers, from the Dead Boys to Buddy Holly, and delved into more personal themes of self-loathing and parental chaos that reflected Jay’s tumultuous childhood. “Sitting in my bedroom, wasting away my youth / I probably need to get a life and stop dreaming of you,” Jay shout-sings on the breakneck teenage anthem “Memphis Blues.” Reflecting on fleeting adolescence like a millennium-era Wilfred Owen, he spits out the line, “These are the best days of my life / They would’ve said if they knew,” interjecting a sneer that underscores the disillusionment of trying to live up to clichéd expectations. Jay’s final declaration serves as an introduction to the way melancholy and rebelliousness coexist across the majority of his work: “I’m a rock & roll kid with the wannabe blues…baby, I got the Memphis blues.”

The sound was raw and exciting, Eric remembers. “Jay’s force of nature was dangerous. It’s also what made him so creative and super interesting. It was right up my alley. Whereas the Oblivians had an ironic take on punk rock, Jay was using our energy as a blueprint to create music that was powerful and unironic.”

The passion Jay brought to the scene was intoxicating, but he was already cementing his reputation as a shit-starter. He couldn’t hold his liquor. He had an opinion about everything, especially other local musicians, who he frequently deemed “a bunch of old dudes playing the same blues-derivative garage shit.” He was constantly agitating other people and disrupting shows (memorably, he used a fire extinguisher to put an end to a performance by Greg’s band the Compulsive Gamblers). It troubled me that Jay ran the Reatards like a tightly wound martinet. It wasn’t a show unless someone was fired onstage by the end of the night, and I didn’t always find it funny to watch. I’d begrudgingly hang out, but I didn’t need Jay pooh-poohing my record collection or throwing beer bottles off my second-floor balcony.

Some nights were even darker.

“Jay had massive anxiety when things didn’t go his way,” Alicja remembers. “He was drinking like crazy, and whenever something triggered him, he blew up. I remember watching him play with the Reatards. Something, anything, happened. Maybe someone’s guitar strap fell, and he went off, microphone against the forehead. People were laughing and saying stuff like, ‘Oh, he’s so crazy.’ Later that night, Jay cried that he had no friends and said that nobody cared about him. He was peeing on himself, and I had to take him home. We were at a stoplight, and I don’t remember what I said, but Jay punched me and tried to crash my car. He said he was gonna kill himself, and he was trying to ram my car into the curb. He wound up bending the axle. I parked as best I could and ran up the street. Jay went inside and started throwing plates and ripping things up. I was expecting a big confrontation, but when I went in, Jay was in bed, snoozing. That experience made any onstage spectacle of his too hurtful to watch, because I knew what was going on in his mind—[thinking] that nobody loved him. It was very un-entertaining. It was painful.”

The connection between Jay’s behavior and his mindset is a big part of my conversation with Greg. “There was a lot of insecurity baked into him,” Greg says. “As much as he loved the Oblivians and full-on copied us, he also said we were the worst band he’d ever heard! With people like that, I think they act that way expecting to get a rise out of others, wondering when people are gonna say ‘I hate you.’ When they act out and their friends keep accepting them exactly as they are, that means they’re safe. Jay would act so outrageously that everyone would back away, and the people who stuck around were who he considered his friends. He was acting in self-defense, trying to keep himself safe by looking so scary.”

I think back to a conversation I had with Jay years ago, in which Greg’s theory was confirmed by Jay himself. “Any milestone in my life has come from completely alienating all the people around me and then putting the pieces back together,” he said in a moment of self-reflection. “Every time I’ve done that, I’ve grown as a person.”

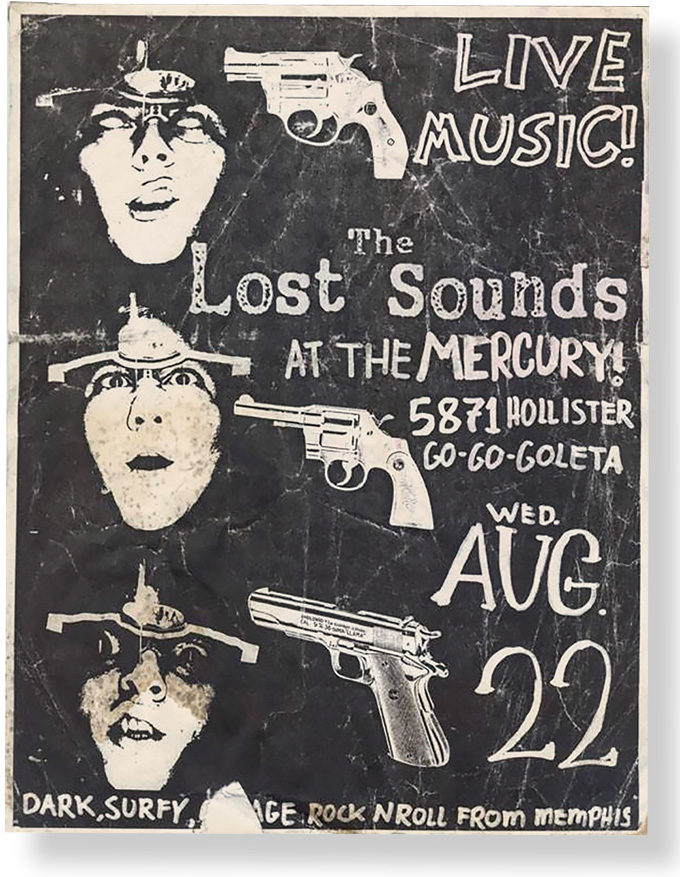

Lost Sounds flyer by Aron Ives. Courtesy the artist

By 2001, the Reatards had temporarily disbanded. Jay had several bands cooking, including Bad Times, C.C. Riders, and Lost Sounds, an experimental synthesizer-based project he created with Alicja and drummer Rich Crook.

“Jay wanted to take a break from the Reatards,” Alicja remembers, “and Lost Sounds was just what happened next. We were drinking all night at parties, and hanging out at home with all this energy, and we set up some amps in the kitchen and started making music. Being in a band that he wasn’t in charge of was maybe a little better for him, or at least it provided a distraction.”

Alicja references other musicians while describing Jay’s talent and process: Howlin’ Wolf, Chuck Berry, the Dead Kennedys’ Jello Biafra. Each one, I realize, is a convention-shattering iconoclast who blended raw emotion and musical innovation to redefine the landscape of American music.

“Jay was a natural songwriter,” she says. “While I’m a natural visual artist, when it came to making music at that time, I felt like I was struggling. I had to force a lot of songs, but when Jay was ready to create something, he was successful every time. It wasn’t without work, because work was a big part of what he did.”

Jay worked hard on and off the stage. He was renowned among local musicians for his professional tour books, compiled long before mobile phones and GPS were ubiquitous. “He had this head for being a manager,” Zac recalls. “He kept a Trapper Keeper with MapQuest maps and phone numbers for everyone. He was a really smart dude, too smart and too big for school. He was constantly observing.”

Alicja remembers that some of Jay’s concepts of how the music industry worked were wildly off the mark, from both the business side and in terms of production. “When he’d record, he’d roll around on the floor screaming into a microphone,” she says, laughing. “He was alone in the house, delivering his vocals.”

In Lost Sounds, Jay’s aptitude for composing shone. The group’s catalog includes hellishly dark numbers like “Soul 4 Sale” and “Blackcoats/Whitefear,” which Alicja cites as two of her favorites. And then there’s the dystopian nightmare of “1620 Echles Street,” named after the address of a Memphis duplex Jay once lived in with Devonna. “Breathe the desperation / And I feel it in the air / Everything’s fucked up and no one even cares,” Jay sings, asking, “Is this life or hell? / I swear I can barely even tell.” The song, Jay later revealed, was about eavesdropping on crackheads as they raped a woman in the adjoining apartment.

I have so many Technicolor memories from that era. First up: Lost Sounds’ performance at the 2001 Memphis Music and Heritage Festival. While most bands played on makeshift stages in downtown streets, Lost Sounds were sequestered to a stage inside Tower Records, which was located a few yards west of the Peabody Hotel. Despite the panes of glass that separated the band from the sidewalk, the noise stopped passersby in their tracks. Somewhere, I have a photograph of two police officers peering in at the spectacle as Jay lambasted the audience with a caustic line. “Spare the women and children,” the twenty-one-year-old snarled, “but I hope the rest of you fuckers go back to Germantown with your ears ringing.”

Next, a show at Murphy’s, a Midtown Irish watering hole. Jay played drums for the Final Solutions, a straightforward punk band he formed with Zac Ives, Justice Naczycz, and Tommy Trouble, though he frequently abandoned his post for sheer debauchery. On this particular evening, he became infuriated by his bandmates’ lackluster efforts, kicked over his drum stool, and made his way around the stage to demonstrate how he wanted them to play. He screamed into the mic, slammed the bass down to the ground, pulled a taxidermy swordfish off the wall and strummed it, nearly smashed a guitar into an autographed portrait of the Who’s John Entwistle, and capped things off by yanking down his jeans and shoving his drumsticks up his ass. At the time, I thought it was just another of Jay’s tantrums. To this day, Zac believes otherwise.

“Our idea was that it should be a show,” he says. “Put it this way: a show can be great for two reasons. Either the musicians are completely on, and it’s a once-in-a-lifetime performance. Or, it’s great because it’s a complete trainwreck because the band is fighting and falling apart. The Final Solutions aimed low more often than not. He’d be Coach Jay, back there just yelling at everybody, we’d make it more ridiculous, and Jay would push it overboard. It was performance, but there was always something a little dangerous about it that would get weirder [based on] whatever toxins people were on.”

By 2004, Jay and Alicja had broken up, though their creative relationship continued—for a time at least. “As much stress as there was in our relationship, at the end of it, we managed to create one of my favorite songs,” Alicja says of the restrained pop-punk number “You Can’t Change,” which was released under the name of Jay and Alicja’s two-piece group, Nervous Patterns, in 2004. “Jay recorded the guitar and drums, I put bass and vocals on it, and he was like, ‘okay, that’s perfect.’ And as frustrated as we were with each other—it was.”

For a while, Jay lived in a cavernous Midtown building dubbed the Peoples Temple, which evolved from a punk rock crash pad into a semi-legitimate performance space. A no-frills room, strictly BYOB. The stage area was in a bunker-like space with low ceilings and a brick wall that absorbed sound. I caught the Japanese garage-punk trio the King Brothers there one wild night that culminated in madness. I showed up with two friends from New Orleans and a full bottle of bourbon. The only thing I remember is standing behind Jay, who gripped his signature Flying V in one hand while swinging from a doorway with the other. He was tall and muscular, and his legs bent to fit the space as he swayed. With someone’s belt in hand, I playfully swatted his ass as he swung back and forth, until we both lost our balance and tumbled to the ground.

The Black Lips, an Atlanta band, played at the first-ever Gonerfest in January 2005. It was the night before my thirty-sixth birthday, and Jay and I fake-brawled on the makeshift dance floor at the Buccaneer Lounge, a ramshackle pirate-themed bar in Midtown. In the absence of a stage, the bands performed on the hearth of an elaborate fireplace. As the night progressed, the line between the audience and performers dissolved into raucousness.

Alix Brown, Jay’s coolly mysterious new girlfriend, was in town. An Atlanta native, Alix played in the early 2000s pop-punk band the Lids, spun rare 45s at DJ nights, and dominated the dance floor like a yé-yé girl magically transported from late 1960s Paris into the American South.

Alix was dancing with us and surfing through the crowd. Halfway into the Black Lips’ set, Jay and Canadian musician King Khan began pissing on guitarist Cole Alexander. “Oh god—here we go,” I remember thinking. Wanting no part of it, I navigated to the back of the room.

“I looked down, and I was covered in pee, too,” Alix remembers, laughing. “It was so gross, but it was so fun—even with the pee. After the show, we all went back to our house, but Jay went on a tirade and we had to get out of there. We tried to leave, but he grabbed some logs in the backyard and wouldn’t let us past him.” As so often happened, a night of destructive fun came unraveled, with Jay’s lifelong fears and mistrust to blame.

“The next morning, he filled out an apology card for me. It was like a Mad Libs: ‘Dear blank, I’m sincerely sorry last night when I blanked.’ That was his way of apologizing, then afterwards we probably went to get Vietnamese food.”

That spring, Lost Sounds toured Europe for several tense weeks. “Jay’s anxiety level was through the roof,” Alicja remembers. “We were a very tight band and we worked really hard, with weekly rehearsals. But if anything deviated, it would set him off.” Alicja, Rich, and bassist Patrick Jordan walked lightly, concerned about what might cause Jay to spiral. Still, Alicja turned down the security of a full-time job for the return trip to Europe. Once in the van, she began to question Jay’s behavior. “It was one thing to watch him flip out with the Reatards, but I started to wonder why he didn’t stop [with Lost Sounds],” she tells me. By the end of the tour, Lost Sounds had broken up. “I decided I was an enabler, trying to pacify his lack of control in the wrong way, which ensured his lack of control,” Alicja says. “Enabling starts with good intentions, but it only agitates the problem.”

I remember seeing Jay and Alicja after their flight landed in Memphis. They both bore physical souvenirs of the end of their band: black eyes, swollen noses. They agreed to share custody of their favorite restaurant, a North Cleveland Street Vietnamese joint called My Thanh. It was funny at the time.

“I found a way to move on,” Alicja says, citing the strong relationships she built with new bandmates in River City Tanlines and MouseRocket. “Jay would call me, not very often, just to talk. We wouldn’t chat for long, but we’d have these very level-headed, rational conversations. He talked about how Lost Sounds was his ‘last real band,’ in the sense that it was a group effort, and he would ask me to listen to his new solo music and tell him what I thought.”

Meanwhile, Jay and Alix’s relationship flourished despite the pissing incident and other manic episodes. The couple bounced back and forth between Memphis and Atlanta. Together, they founded a vinyl-only label called Shattered Records, and a new band called Angry Angles.

“We were staying home a lot and recording music,” Alix confirms. “It was a honeymoon period, and everything happened organically. Jay was always making music, recording things, layering guitars, and bashing on drums. Being around him, you just got sucked into it. He invited me into that world, and I felt really lucky to be part of it. I had been living with Mark Naumann who runs the label Die Slaughterhaus, which inspired me and Jay to start our own label. Then [in 2005] we put out the Angry Angles 7-inch. On the cover, we’ve both got black eyes. They aren’t real—I did that with makeup.”

Musically and visually, Angry Angles was a visceral reaction to the experimental, doom-obsessed aesthetic of Lost Sounds. Angry Angles distilled 1980s New Wave, à la Devo and Wire, into aggressively minimalist pop-punk. With Jay on guitar, Alix on bass, and former Reatard Ryan Rousseau and New Orleans musician-turned-chef Paul Artigues taking turns behind the drums, they recorded a slew of 7-inch singles, most notably the kinetic “Things Are Moving,” an apt description of Jay’s apparent evolution as a musician and a romantic partner. The shifting dynamics expressed in the song, which Alix co-wrote, seemed to underscore Jay’s embrace of new ideas. I remember listening to it and thinking, optimistically, that Jay had grown from his previous experiences, realized what he wants and needs in a partner, and achieved a kind of emotional maturity. Then as suddenly as they emerged, Angry Angles broke up.

“It was fun until we went on the road,” Alix says today. “Jay had anger issues, and people wanted to see that. Playing with him, and seeing him work out those issues, created a volatile environment. In some ways, he felt indebted to be what people wanted to see, and it was harder for him to disassociate once he got back home.”

Jay Reatard in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 1999. Photograph by Pete Jay

During what Alix dubbed their “honeymoon” phase, Jay was building the music that would become his debut solo album. Initially released on the garage rock label In the Red in 2006 and later reissued by the Mississippi-based Fat Possum Records, Blood Visions stands as the defining work of Jay’s career. The album cover features a photograph of Jay, stripped down to his underwear and covered in raspberry syrup. Thematically, Blood Visions is rife with paranoia and nihilism, with urgent lyrics that touch on Jay’s ever-present anxiety, alienation, and penchant for self-destruction. It’s melodic yet incredibly fast-paced, with most tracks clocking in around two minutes or less. “I look into your eyes / And try not to cry / Think about time gone / Let’s hope it’s not wasted,” Jay sings on “Oh, It’s Such a Shame,” a catchy and complex manifestation of pure melancholia. Feelings of disappointment, longing, and a Night of the Hunter–esque battle between love and hate stretch across the album, especially on the tracks “Waiting for Something” and “My Shadow.”

Blood Visions introduced Jay’s music to a legion of new fans who were attracted to the album’s raw energy and Jay’s reputation for ferocious, unrelenting live shows. High praise from music critics who fell over each other in their attempts to laud Jay’s craftsmanship and intensity, combined with the indie credibility of In the Red, solidified the album as a cult favorite. Jay recruited bassist Stephen Pope and drummer Billy Hayes from the Memphis garage scene to back him when performing his new solo material live.

“I remember sitting in the Buccaneer parking lot inside Jay’s car, a 1993 Ford Taurus,” Stephen Pope tells me. “We did Ecstasy. We were trying to buy cocaine, but okay. We listened to Blood Visions ten times in a row, and then Jay asked us to join the band. Our first tour together was seven weeks in Europe. After the first show, Jay told me he’d fire me if I ever wore khakis onstage again, and he bought me a pair of jeans. I’d never even put any thought into what I wore before, but Jay told me I looked like shit.”

Although Jay was at his most prolific during this time period, his antics on and off stage were increasingly controversial. “Jay was really out there,” Zac says. “He was testing his own boundaries and seeing how far he could run with it. He went one hundred fifty percent with everything, which led to some greatness and some colossal disasters.”

In 2008, while performing the Blood Visions cut “My Shadow” at the Silver Dollar in Toronto, he threw a punch at a stage diver. It was, in many ways, a shot heard around the world. Music blogs big and small reported on it, and at the time of this writing, a YouTube video of the incident has over 77,000 views. Following the Toronto gig, fans felt empowered to confront Jay in the middle of his shows.

Stephen notes how proud Jay was of Blood Visions—and how everything changed once the video of the fight at the Silver Dollar was posted online. “Instead of enjoying the music, people just came to shows to see Jay fight or blow up. It made us a bigger band, but it took the focus away from a great album and it made Jay into a clown. He was easily provoked, so it happened a lot.”

Around that time, Jay and I had an earnest on-the-record conversation about everything that was happening—the toxicity, the fighting, and his proclivity for cocaine use, which fueled other negativity—all of which I considered a huge distraction from his craft.

“I used to be able to see a distinct line between me as a person and me as an artist, but they’ve both moved towards the center until I don’t feel like there’s a difference anymore,” he told me. “The only thing that limits me is my skill as a musician.”

Jay began trading his Flying V for an acoustic guitar as a way to antagonize those so-called fans. “I have people coming to my shows and asking, ‘Why aren’t you bleeding every night and why aren’t you screaming at the top of your lungs and why aren’t you pissing your pants onstage?’” he told me. “All these antics, which weren’t antics when they originally happened. I’ve felt a need to clean house, and I figure that the easiest way to get rid of them is to do exactly what I want to do. It just took a level of confidence to go, you know what? Fuck these people and their sense of entitlement. Fuck off—I just want to do what I want to do.”

Nevertheless, Jay would call me from the road to verify that yes, he’d parted ways with his rhythm section, Stephen and Billy, which he announced via Twitter (“Band quit! Fuck them!”). Or yes, he’d kicked someone in the face onstage in Las Vegas. At the time, I was writing a music column for the Memphis Flyer alt weekly. Fodder from Jay kept me busy for weeks.

“For Jay, the spectacle was ingrained, although it didn’t always come out,” Stephen says. “If he was in the right mindset, which he was for the majority of 2006 to 2008, he was very focused. We practiced all the time, and we toured all the time. He wanted the band to be very tight, but he could only stay focused for a certain amount of time before he had to find some kind of release.”

In early 2008, Jay had signed a six-figure multi-record deal with the indie giant Matador Records, the label that helped launch the careers of Cat Power and Pavement. Beginning with “See/Saw,” which was released on April 8, they cemented the relationship with six 7-inch singles. “Jay was a killer songwriter, a dynamic performer, an awesome guy,” Matador co-founder Gerard Cosloy says. “We liked Jay exactly as he was—it was a no-brainer for us, provided we could make a deal, and we did.”

I was so happy for Jay. In hindsight, he was internally and externally raw. I missed the cues initially, but today, the lyrics on the twelve Matador sides leave me cold. “A see-saw, a-back and forth again / You don’t like what you see / You must not care for me,” Jay sang on his first Matador single, a rhyme that echoes the insecure paranoia that Alicja told me she couldn’t unsee. “When I was a young boy, I didn’t need much / A kind word or two, or a warm touch / But instead, I got a man / With an empty beer bottle in his screaming hand,” he sang on another. His words stand in sharp juxtaposition to the bright and happy music beneath them.

I asked Jay about that contrast once, and he responded by saying, “People always think the Beach Boys were the happiest band in the world.” Today, when I listen to the lyrics of “Screaming Hand,” I think of the overbearing Murry Wilson, who allegedly forced his son Brian to shit on a plate and once hit him so hard that he caused permanent deafness in one ear, and I feel sick.

Lamplighter Lounge, September 2022, Memphis, TN. Photograph by Mark Murrmann

Jay and I saw a fair amount of each other in 2009, but that Beach Boys anecdote was the closest we came to discussing his new lyrics. He told me he was sick of partying, though. After a turbulent tour with the Black Keys, Jay briefly quit drinking and bingeing. I was saddened to see his last meaningful romantic relationship—with Lindsay Shutt, a visual artist who had relocated to Memphis from Cleveland, Ohio—grind to a halt.

Jay came to a dinner party at my house and pulled one of his old tricks, feigning tiredness and crawling into my bed until the other guests had left. Then he came to life, playing records and eating leftovers and talking until dawn. We were both new homeowners, and we planned a trip to the nearest IKEA, which at the time was over four hundred miles away. One magical night I walked into the Lamplighter, a Midtown dive bar, with the producer Scott Bomar, once a short-term bassist for the Reatards, and encountered Eric, Zac, and Jay. Even though there was a pair of young filmmakers in tow documenting Jay, it felt like old times.

Watch Me Fall was released on Matador that August. It was a polished, vulnerable album that marked an artistic departure from everything that came before it. The music was simpler and more poppy than I expected. I wrote at the time that the melodic break at the end of “Hang Them All” was a big “fuck you” to anyone who ever purchased a Reatards record. It’s a beautiful LP, but Jay sounded more lonely and frustrated than ever. From the album title, which sounded like a doubling-down on Jay’s antagonistic posturing, to a conversation we had shortly before its release, Jay seemed fatalistic. He was, he insisted, continuing to play with listeners’ perceptions.

“With my solo music post-Blood Visions, everything I’ve done is a juxtaposition,” Jay said. “You hear a song and think, ‘oh yeah,’ and then you listen a second time and you realize it’s about hanging yourself or something.” The interview was for a major feature in eMusic, and Jay willingly opened up about whatever I wanted to ask.

“Up till now, I just wanted to get to make the next record, and as long as I could survive until then, I could make that one and then survive until I made the next one,” Jay told me. “That’s as far ahead as I ever worked—about twelve months. If I’d been goal-oriented, I wouldn’t have done everything I did, because I was focused on being youthful and ignorant, feeling immortal and thinking I could get away with doing whatever I wanted. Post twenty-six years old, I started thinking about it a little differently. I’m not gonna live forever, my health is gonna fail, I need a place to live.”

We were sitting knee-to-knee at my kitchen table. I probably made coffee; I remember Jay had a brand-new MacBook he brought to show off. I commented that the frantic kid I’d met at Shangri-la was long gone.

“Either I grew up, or society broke me down,” he said. “Either way, I started thinking more about my future, which is the opposite of everything else I’d done up to now. I’m not gonna be thirty-five years old, still going around getting people to call me ‘Reatard,’ because it immediately turns people off. But I’m fine with it for now—I look at it as a filter, a litmus test for assholes. If you can’t get past the name, then you can’t afford the price of admission.”

The conversation reaffirmed everything I understood about Jay—all the positive things he offered, plus all of the bullshit that came along with them. At every stage of his too-short life, Jay was a walking dichotomy, his psyche exhausted by the constant battles between his opposing values and behavioral contradictions. Jay’s actions were extreme and complex because inside, Jay was extreme and complex.

I only saw him a few times after that. I caught him onstage at a handful of shows, including one in Portland, Oregon. Jay seemed like he was racing against time, performing his songs in sheer cathartic release while keeping one eye open for confrontations. The band sounded especially tight, and, despite the volatility that had marred so many gigs, Jay seemed confident.

In December 2009, two concertgoers were arrested for attacking Jay during a performance at Emo’s in Austin. Two months earlier, I remember Jay jumping onstage during the San Francisco queercore band Hunx and His Punx’s Gonerfest 6 performance and pantomiming fellatio with frontman Seth Bogart and several other exhibitionists. There was nothing sexy about it, but it remains one of the funniest rock & roll moments I’ve ever witnessed.

To promote Watch Me Fall, Jay embarked on a month-long tour that consisted of free in-store performances at independent record shops. I thought that was cool, but he was apparently annoyed by the whole situation. He intentionally binged before every show. Most of the times we crossed paths, he was blitzed out of his mind or surrounded by sycophants. I didn’t want to appear overeager about his newfound fame, or overly concerned about his drinking and drug use. In hindsight, I really fucked up.

We never made it to IKEA. Jay died in his newly purchased Midtown house in the early morning of January 13, 2010. He was twenty-nine. I heard he thought he had the flu; as it turned out, he died of an overdose of cocaine and alcohol. Before the news got out, I’d already driven across town for another memorial—Poppa Willie Mitchell, the iconic soul producer at Royal Studios. After the service, I turned on my phone and saw the flood of missed calls and messages.

Jay’s funeral, which was held three days later, is a blur. I have a vague recollection of seeing Devonna for the first time in over a decade and listening to Eric Friedl delivering a stunningly sad eulogy that, above all else, spoke truthfully about Jay’s life and what has become his legacy. After the memorial, we went across the street to watch, graveside, as Jay was interred with his Flying V.

Since then, monuments to Jay have come and gone. In 2014, artist Lance Turner painted a mural of Jay in downtown Memphis. In his artist statement, Turner notes that “the out-of-focus pixelation depicts a memory that is simultaneously fading away and becoming legendary.” Around then, they tore down Jay’s childhood home on Dunn Avenue. It was from that house he’d mailed me his first two demos. Both things startle me: Jay’s oversized visage glaring out over South Main Street, and the wound of a driveway leading into an empty lot.

This story was published in the print edition as “Rock & Roll Kid.” Subscribe to the Oxford American with our year-end, limited-time deal here. Buy the issue this article appears in here: print and digital.