Rude Angel

We’re all in the backseat of Lorette Velvette’s V8 Ford

By Stephen Deusner

Photograph by Trey Harrison

Lori Godwin drove her Chevette to Memphis the first chance she got. Growing up in Savannah, Tennessee—just two hours away but a completely different world—she visited the big city during family trips in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and the place stuck in her imagination. Her older sister, who married and moved to Memphis, would call home and place the phone next to the radio so that Lori could stay up late listening to WEVL. Those were calls from a planet many galaxies away, full of new wave, punk, blues, pop, and other strains of music that hadn’t trickled down to her small town. In January 1982, just months before she would have graduated high school, Lori couldn’t take it anymore. She packed up her hatchback, crossed the Tennessee River, and sped down Highway 64, through Selmer and Bolivar and Somerville, until she hit the Antenna Club.

Within days she was entrenched in the local music scene, and within weeks she traded her beloved marching band flute—severely dented after she slammed it in the car door—for an electric guitar, a trusty and mischievous Gibson Challenger. She still plays it today, but at the time she barely knew any chords. Her new beau—Tav Falco, already tweaking old blues and rockabilly tunes by then—taught her the basics and the rest she picked up studying recordings by the old bluesmen themselves, in particular Jack Owens and Fred McDowell. “Special Rider Blues,” the Skip James version, became her favorite song. “It seemed like a style that you could be pretty loose with,” she says, more than forty years later. “You didn’t have to be precise. As someone just learning guitar, I felt very connected to it somehow.”

Through Tav she got an audition with Jessie Mae Hemphill, the hill country blues she-wolf who had just recorded her debut album at sixty years old. Lori nervously performed Billie Holiday’s “Fine and Mellow,” after which Hemphill laughed cryptically and gave the young woman two things: a nickname, Mellow Yellow, and her first gig. Lori backed Hemphill a few nights later at the Antenna Club. “I was very super scared. When I got up there, I turned my amp basically off and just tried to play along with her—it was terrifying.” But it was also thrilling.

Upon joining Tav Falco’s renowned backing band Panther Burns—whose members were either virtuosic or barely capable on their instruments, but rarely in between—Lori Godwin adopted a new stage name, Lorette Velvette, and never turned her amps down again. Thus was born one of Memphis’s great unheralded guitar heroes and performers: an artist who covered David Bowie and the Stooges alongside Eddie Floyd and R. L. Burnside and who sounded utterly convincing and compelling in every setting. She made great records with her bands in the ’80s as well as a trio of excellent solo albums in the ’90s, but they’re almost all out of print and difficult to find. She has been elusive, never as popular as her peers but absolutely essential to the story of local music. Like Falco before her and like so many after, Lorette Velvette showed how Memphis might reach beyond the city limits for new sounds and ideas, how it might bring its own past forward into the future.

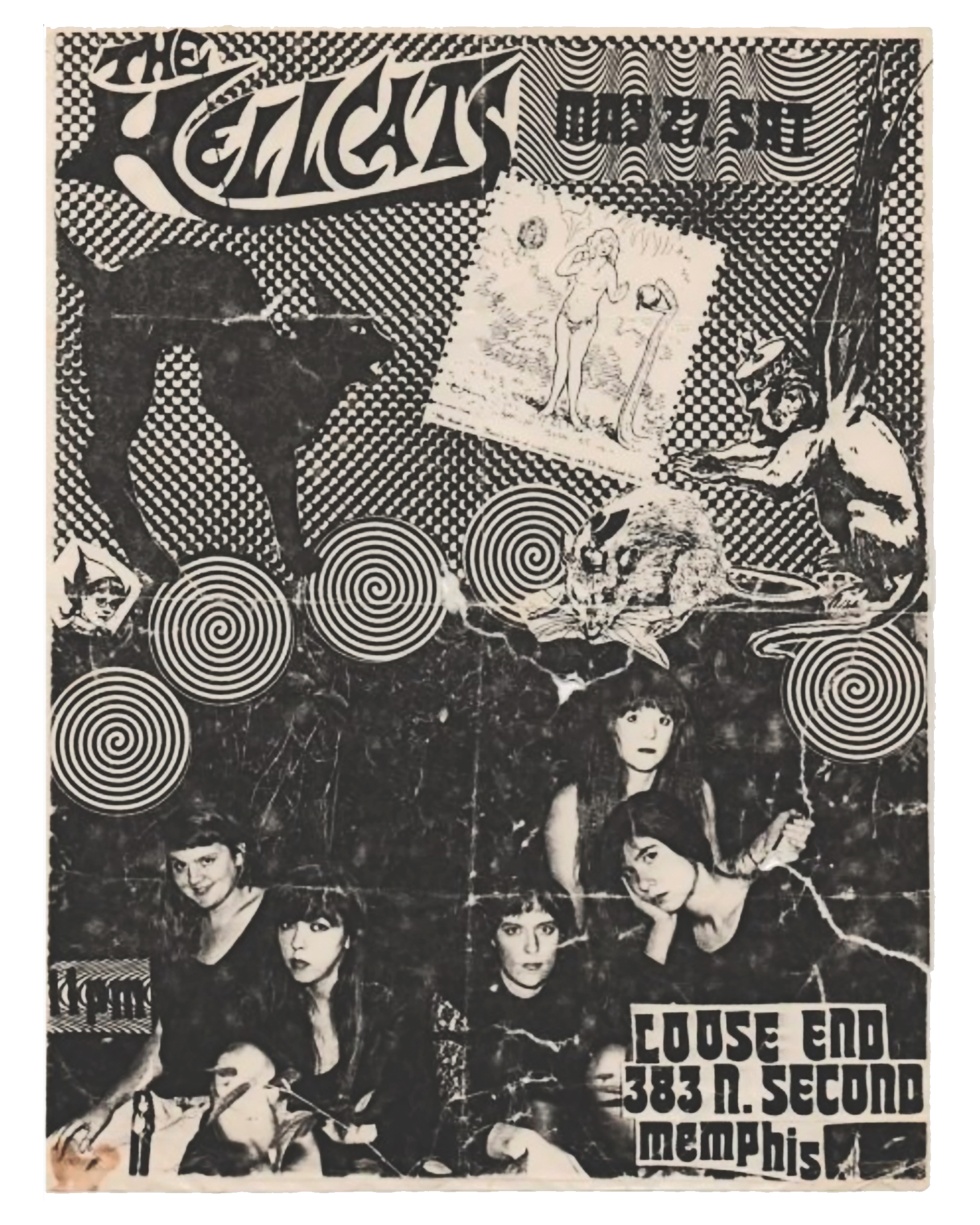

Flyer courtesy the Hellcats, ca.1990

She brought glam to the blues and vice versa, a little bit of punk to everything. She knows it’s all based on stomp and swagger. Just listen to the way she underpins “Come On Over” with a snaking snare rhythm learned from the Mississippi fife-and-drum legend Otha Turner, whom she visited many times at his Mississippi home and even opened for in Memphis. Or listen to the way she bends her voice on Floyd’s “Oh How It Rained,” dropping it down to a low, intimate recitation, recasting a cover song as her own internal monologue. Or listen to her singing Bowie’s “Boys Keep Swinging” and T. Rex’s “20th Century Boy,” redefining both songs not only with the ferocity of her performance but with her refusal to change the nouns from masculine to feminine. Every Lorette Velvette song struts, even the slower ones.

Her bravado helped revitalize—creatively if not commercially—what had become a ghost town in the 1980s: Elvis Presley was dead, Chris Bell was dead, Alex Chilton had skipped town, Stax had shuttered, and the local music infrastructure had withered. She says, “It was pretty depressed, and there weren’t a lot of places to play. There weren’t a lot of places to hang out. But there were some bright spots.” One of those bright spots was the Antenna Club, which had opened less than a year before Velvette arrived in Memphis but had already become the locus for the local rock scene. Another was Decadence Manor, a thrift store whose owner lent Velvette and other punk kids clothes to wear to the Antenna, whether they were performing or not.

Velvette spent the ’80s backing Falco in Panther Burns (and the Burnettes) and co-fronting an all-girl group called the Hellcats—all of whom were rip-roaring singers and players. When that band dissolved, she toured Europe as part of a lineup with Townes Van Zandt and Alex Chilton at the top of the bill and Memphis oddballs the Country Rockers near the bottom, and she can still regale you with wild stories of early-morning drinking jags and back-of-the-bus poker games. When a German label expressed interest in releasing a Lorette Velvette solo album, she sheepishly asked Chilton if he would produce it, not expecting him to actually say yes. “What he did was, he brought a set of drums and a bass to my little duplex. I already had a piano and a guitar. He showed me how to use a four-track recorder to make some demos, and that was the basis of that first CD.” That was 1993’s White Birds, which includes Velvette’s ode to Memphis “Godforsaken Town,” her cover of Burnside’s “Going Down South,” and one of her finest songs, “Eager Boy.”

Featuring Chilton playing bass, “Eager Boy” is a blues plaint dressed up as a sloppy rockabilly toss-off, with Velvette’s guitar constantly steering against the skid of the groove and interrupting her vocal: a devil on her shoulder. She injects every lyric with a casual, almost sarcastic lust, conveying as much of the story in her sighs and caterwauls as she does in the words themselves. But the words themselves contain so many fraught blues images you might suspect the song’s a cover rather than an original. “Awwww eager boy in the backseat of my V8 Ford,” she moans. As soon as she finishes this song, she’s climbing back there with him.

Lorette Velvette at Barristers, Memphis, 1996, with Melissa Dunn (guitar), Doug Easley (bass), and Kurt Ruleman (drums). Photograph by Dan Ball. Courtesy the artist

Velvette made two more solo albums in the ’90s—1995’s Dream Hotel and 1997’s Lost Part of Me—and she also sang backup for Sonic Youth, hung out with Jeff Buckley, and played in a band called the Kropotkins with the Velvet Underground’s Moe Tucker. She released a badass career retrospective, Rude Angel, on the short-lived label Okra-Tone in 2000, and then…she went back to Savannah. Or, more precisely, thirteen miles past her hometown, to the small community of Olivehill, said to be one of the darkest spots in Tennessee and therefore the best for stargazing. There she stayed for two decades, raising two kids and sending them off to their own big cities. In February 2023, Velvette dusted off the Challenger, reacquainted herself with old tunes, wrote some new ones, and started performing again in Memphis, usually at low-key venues like Bar DKDC. “Now I do it for myself in a big way. It’s a practice in the same way that any art is a practice, yoga is a practice. Being creative is a practice that you do to keep yourself vital to yourself. It keeps you healthy, which is why I’m back at it.”

Even with new shows on the books and new music in the works, there remains a bit of mystery to Lorette Velvette, whose records were scarce in the 1990s and are even more elusive thirty years later. She worked almost exclusively with European labels, including the legendary New Rose Records in France, Au Go Go in Australia, and Veracity in Germany, not out of any creative consideration but because they were the ones who first expressed interest in releasing her music. As a result, she’s not understood the way Alex Chilton or Tav Falco are understood—as someone so closely associated with the city that they’re inseparable from the place. But Velvette still exudes a very particular kind of Memphis cool, still embodies a rebellious impulse that feels very local. Her songs are rooted in the past—the region’s past, her personal past—but she herself remains in the present, in whatever feeling she finds in the lyrics or in the riff. Listening to her songs today is like hearing a transmission from a faraway place, similar to what teenaged Lori Godwin heard over the phone lines so many years ago.