The Machine in the Garden

After decades of unchecked hazardous waste pollution, a Florida hamlet fights the developers eager to build homes there anyway

By Jordan Blumetti

Front entrance of the abandoned Florida Solite plant. Photograph by Jordan Blumetti. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are by the author from June and September 2024

FISSURE

First came the notices for rezoning and the announcements from development companies that wanted to “build your dream home.” NEW MODELS OPEN and NOW SELLING and $0 DOWN beckoned from streamers and billboards. The new neighborhoods were given dulcet, meaningless names advertised on foam-core signs, evoking a fantasy of pulling up stakes and moving to this leafy sanctuary away from the cities and snowbirds and coastlines—back to the country, where there’s still enough forest to hide your sins—and planning out the best days of your life. But that message is complicated by a different type of sign across the street, one that has you preparing instead for the end of your life, with visions of biohazard symbols, skulls and crossbones, and the words STOP TOXIC SOLITE alongside LEAD, DIOXINS, AGENT ORANGE, ARSENIC, and CYANIDE.

The neighborhood of Russell Landing is old world, as far as Florida goes. It stands against the tide of shoddy new construction in tattered, eclectic defiance. I crossed the train tracks guarding the lone entrance, passing a few dozen houses along a two-mile elbow of blacktop intersected with russet dirt lanes that had been stamped out of the surrounding longleaf pine forest. It was a Sunday afternoon. Trucks were parked in front yards, aprons of dried oak leaves around them, next to a cruciform PVC sculpture marking buried septic tanks. After a bend in the road, I stopped in front of a farmhouse painted a cheery eggshell color. It had side gables and a deep porch where a compact woman with dirty-blond hair waited to pull me inside. I’d seen Kristen Burke’s name in the local paper and read of her quarreling with real estate developers and the Florida statehouse about a toxic mess lurking next door to her house. From 1959 until 1995, a mineral company that produced a lightweight concrete aggregate used as construction material operated an industrial plant on an adjoining property. The company, and the product itself, was called Solite.

Kristen introduced me to the two men standing sentinel in her kitchen: Harold, her husband, and next to him, Mike Zelinka, a former employee of Solite who appeared more than a little circumspect, rocking on his toes, hands stuffed into his front pockets. On the dining room table Kristen had spread maps, enlarged satellite images, and aerial photographs of the roughly thousand-acre forest separated from her backyard by a narrow pond and a man-made berm. Then as now, that all belongs to Solite, Kristen explained, but the main area of production was only about one-third of the property set in the middle of a dense upland swamp. The photographs showed a transformation in that clearing over a span of half a century, beginning in the late 1950s and looking ten years later like a bomb had gone off. The land was chewed up and brown from pit mining; piles of clinker and slag, catwalks, belts, and ditches draining into shallow ponds all surrounded the plant’s beating heart of colossal rotary kilns where raw clay was baked at two thousand degrees.

This story was alien to Kristen when she moved to the neighborhood twenty years ago. “Things changed pretty fast in 2018,” she said. “That’s when the first of the rezoning signs appeared.” Kristen and her neighbors learned of a public hearing with the local planning commission where a developer and the former plant manager—a man called Albert Galliano, who still works for Solite’s parent company—were proposing changes to the zoning codes to allow for residential building on the property. Homeowners packed the county chambers, and a torrent of long-standing grievances followed. The company had disappeared in 1995 when there was known pollution on their property. That was bad enough, homeowners said, but since then, Solite has claimed that the contamination was confined to the central node of about two hundred and thirty acres. The community had reason to believe otherwise, alleging that decades of unchecked air, soil, and water pollution had migrated farther afield and contributed to a pattern of environmental cancers, heart disease, birth defects, and rare genetic disorders spanning generations. The way they saw it, the company drained mineral resources, made its money, and absconded without answering for what it left behind. Now it was back, twenty-three years later, to cash in on Florida’s housing market—colloquially known as the last crop.

“The primary concern is that construction equipment will stir up all the toxic sediment that had settled in the ground and in the lake beds all those years ago,” Kristen said. “We couldn’t let that happen.”

The planning board ultimately turned down the proposal, but developers made clear they weren’t going anywhere. Kristen became the de facto spokesperson, which turned into a campaign for county commissioner, a seat she has held since 2020. “I figured out [Solite] was private property, and the county can’t really do anything about it.” By the summer of 2023, she’d helped start a citizen advocacy group dubbed the Solite Task Force. This was the group responsible for the foreboding panel signs I’d seen up and down County Road 209.

She approached the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) for soil and water sampling of the entire property. The state balked, saying it had no reason to believe allegations that the pollution was more widespread than Solite had led regulators to believe. So she paid for the testing herself. The results brought a grim validation: cadmium, barium, lead, chromium, and arsenic, among other metals and acids (some below and others above the legal threshold), were detected in their own yards, including the pond behind Kristen’s house, which had formed many years ago from drag lines digging out a vein of clay.

On Kristen’s table, we turned to the more recent satellite imagery. One structure—a hollowed-out former office—was still visible through a sparse canopy, but new vegetation had reclaimed most of the clearings. Splashed across the map was a series of nine irregularly shaped lakes. One looked like a giant puzzle piece with blunt peninsulas jutting out from its banks; one looked like a duck head; one looked like the state of New Jersey.

Mike Zelinka stepped forward and landed a broad finger on a lake next to the office. “That was the scrubber pond, but we called it ‘the nightlight.’ It glowed greenish yellow,” he said.

The glow was the result of contaminated water that drained through a series of unlined ditches. Even from the old photocopies, the lake had a milky green vibrance. The ditches were supposed to prevent water from overflowing when it rained. “It wasn’t deep enough. Whenever there was a nasty storm, that water went everywhere, all the way down to Russell [Baptist] Church.”

Mike traced his finger to another lake opposite the scrubber pond. “That’s where everything went when they left in ’95,” he said. I asked him to clarify. Into the lake, was what he meant. “That’s right—nothing ever left that property.” All the machinery from the plant, everything visible in the old aerial photographs—catwalks, kilns, trucks, chemical tanks—was reportedly dumped into that lake, where it remains today. “See them peninsulers?” he continued, pointing finally at the largest lake on the property. “Those are man-made. And they’re all there for a reason.” In his yawning drawl, Mike submitted that the “peninsulers” were created as interments for fiberglass drums filled with overflow waste. “I put dirt over top of ’em,” he said. “I was told they were empty and clean.”

Aerial image of Florida Solite. Colored dots indicate dumping sites and similar areas of concern. Courtesy Kristen Burke

One of the ongoing controversies is the persistence of these blue barrels, which are technically called “burials,” a provocative term of art in hazmat parlance. Whether through erosion or having not been sufficiently buried to begin with, they are visible outside of the Solite boundary. Kristen asked if I wanted to see one. We loaded up in the Burke family golf cart, and Harold drove to the end of the street. A thin rain drummed the plastic roof, and the pines nodded in concert. Harold pulled off at a three-way stop where the woods began. I could see a warped chain-link fence through the trees, metal signs bleached from the sun dangling from its rusted fabric. Behind it loomed the fifteen-foot berm.

“There’s one,” Kristen said moments after stepping over a narrow ditch and into a thicket of palmetto trees. But it wasn’t just one. There was a raft of deteriorating blue barrels half-entombed on a random axis along the fence, like Bud Light cans chucked from a car window. Steel and fiberglass barrels have been one of the chief hazardous waste containment and disposal methods since the 1940s. “By the 1980s, the 55-gallon drum was synonymous with hazardous waste and the problems posed by late industrialism,” writes Rebecca Altman in the Atlantic. “The drum signified the long-term consequences posed by short-term fixes and society’s failure to manage a cascading problem.”

Associations with Love Canal, an abandoned dredge project in Niagara Falls, New York, come easily to the fore with the image of the blue barrel. In the 1940s, under government sanction, a chemical company began using the partly dug canal as a hazardous waste dump. The landfill consisted of 21,000 tons of toxic chemicals and carcinogens, dioxins among them, and was capped with clay then sold off to the Niagara School Board and later to developers. By the 1970s, the water table had risen and the chemicals had filtered into the basements and yards of the adjoining working-class neighborhood and the public-school playground that was built over the dump. Kristen hadn’t wasted much time before invoking the environmental and health catastrophe in Niagara, where, as Altman writes, thousands of these barrels had been interred.

Mike Zelinka lowered himself to one of the drums that had been split open and pointed at the rim. Whatever was inside had long since leached into the soil. The contents had corroded the fiberglass. “You see the dark brown? Normally the inside of fiberglass barrels are white, or an off-white. But that’s brown. That tells you it’s a very hazardous acid. They didn’t care where they dumped, they just dumped.”

We crawled out of the scrub to find that the rain had stopped and the sun was beginning to tuck behind the trees, throwing most of the neighborhood in shadow. There was a row of houses across the street that all backed up to a narrow band of water—what the Burkes referred to as a canal, though it was more of a glorified ditch—running for a half mile and emptying into Black Creek. “Do you hear that?” Kristen said. The faint sound of rushing water. She pointed to a culvert underneath the road that was built to convey stormwater from Solite into this canal. The outfall of that culvert was another of the recent test sites where arsenic, barium, cadmium, chromium, and lead were discovered.

Before we lost the rest of the daylight, I suggested a trip to the main entrance of the plant. Harold returned us to the house and stayed behind while we traded the golf cart for our cars. I followed Mike and Kristen as they turned a corner and crept down a dead-straight and busted service road overgrown with crabgrass. To my right were simple wood-frame homes and trailers; opposite them were the train tracks I’d crossed on my way in. As we got closer, I saw two columns of cement blocks climbing diagonally toward a twenty-foot-high metal gate that looked like the driveway of some B-movie recluse. Two white NO TRESPASSING signs were affixed to the top panel, which at a distance looked like a set of inquiring eyes. We left our respective vehicles and stalked in front of it. An impression of the words SOLITE and OLDOVER could still be seen on the facing of the concrete pillars.

Kristen said she should be getting back, and then it was just Mike and me listening to the crickets and frogs in the marsh. His once-sturdy military frame had gone slanted and rotund. Mike had done two separate stints at Solite in the early 1990s, broken up by his Army service. He explained the process of making concrete aggregate while staring vacantly over my shoulder, as if visualizing the raw clay spinning in hoppers, hearing the whine of the kilns and watching their slow revolutions as the cooked aggregate fell rhythmically to the ground. One of his jobs was to crawl fifteen feet underground to grease the triangle belt drives. He said employees weren’t instructed to wear protective gear, and his skin would tingle and burn when he climbed out. “You see these funny colors?” He pulled on his collar and pushed up his shirtsleeves. The skin was speckled and pitted like terrazzo. “That’s from chemical burns.” The chemicals were stored openly and spilled often, he said. They’d burn through shoes—“two pairs a week”—and the heat from the kilns ate through metal catwalks. “Got so hot you’d feel it twenty feet away,” he said. “You’re not supposed to feel that.”

Mike Zelinka, former Solite employee.

Mike’s story takes a further unhappy turn. He had a heart attack in his late twenties that nearly killed him. It happened on one of his days off, when he was grocery shopping with his wife. He pulled at his collar again, a little more this time, to reveal a lateral scar on his chest from surgery. He said the doctors found high levels of arsenic in his blood, a known cause of cardiac failure. Once he’d recovered from the heart attack and returned to work, Mike started questioning management about the episode. “I said, ‘if we’re dumping chemicals around here and you’re not doing anything about it, then you’re in the wrong, not me. I’m only doing what I’m told.’ I’m ex-military, I’m a soldier, I do as I’m told. But that manager, he just looked at me and said, ‘Give me your hard hat, you’re done.’”

Six months later, the plant was closed.

The next time he saw his manager, Albert Galliano, was at the 2018 planning commission hearing. After the meeting, he cornered Galliano. “I looked him square in the eyes and I told him: ‘You’re a sorry son of a bitch.’” He was spitting mad. “You allowed this shit to go on and you didn’t do a damn thing about it. So if you want to kill me, then kill me now. I’m already halfway there.”

Mike was given to histrionics. I’d noticed this had a certain effect on people, made them uneasy, like you never knew what he was going to come out with. It was that and his physical presence—a perpetually knitted brow, unsmiling mouth, likely because of his teeth, which were barely there. Like the bad heart, he chalked this up to the years of arsenic exposure. Though I’d be remiss not to mention that he often spoke through a cloud of cigarette smoke.

He grew up a mile from here, next to the Baptist church, where his father was the longtime caretaker. He’d since moved a few towns away, but this fight against his former employers seemed to provide a renewed sense of purpose. “It’s a nightmare, especially for these people around here. This is my community,” he said. “We’re going broke doing this, but right now my conscience needs to be fully clear.”

Top: Demolition in Love Canal, June 17, 1982. Bottom: Children play in a backyard adjacent to rising toxic waste in Love Canal, Niagara Falls, New York, ca. 1978.

Both courtesy University Archives, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

MINERAL

Russell Landing is in a town called Green Cove Springs in north Florida’s Clay County: over six hundred square miles of amphibious pine forests hugging the west bank of the St. Johns River between Jacksonville and St. Augustine. Founded in 1858, Clay County is named after Henry Clay, the Kentucky congressman and ninth U.S. secretary of state, despite the congressman having no connection to Florida and never visiting in his lifetime. I’m told by local historians that the presence of vast mineral deposits of clay was just a coincidence vis-à-vis the county namesake. The deposits formed twenty million years ago beneath the floodplains of St. Johns tributaries. Very old basement rocks and the slightly younger chalk-white limestone slab of the Floridian aquifer were covered with soil and peat terraces from ancient seas all overlain with quartz, coquina, and clay.

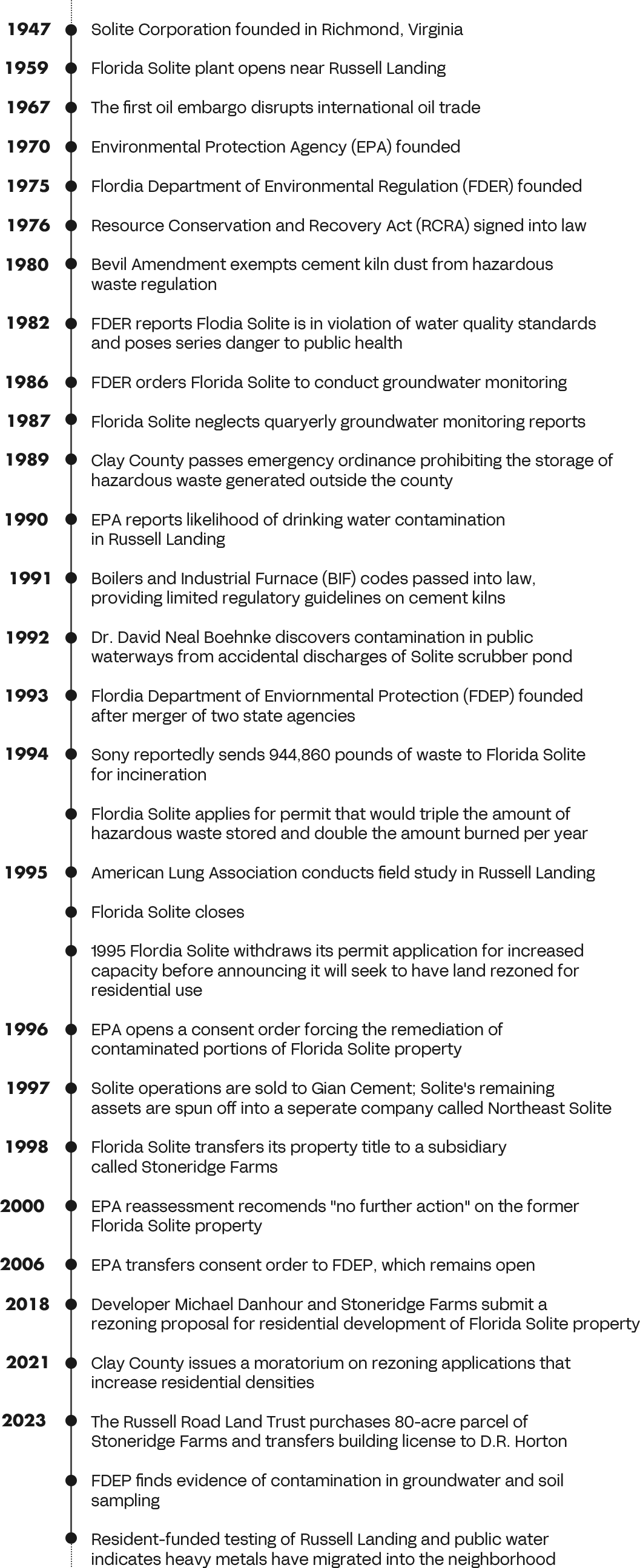

By 1950 turpentine and industrial logging had denuded the blackjack ridges of oak and pine beyond recognition, leaving bare, inky creeks and dime-sized lakes shining like cow pupils. Around that time, a forty-year-old engineer from Richmond, Virginia, named John Watts Roberts traveled to north Florida on a prospecting mission. Roberts had recently acquired a patent for 190-foot-long, twelve-foot-wide rotary kilns that superheated shale to produce a porous, lightweight rock. The heat chemically altered the clay, expanding its water content, allowing for a durable and more cost-effective alternative to cinder blocks, at the time the industry standard for construction. All he needed were the raw materials, which he found in spades. Armed with the patents, and under the auspices of his newly incorporated Southern Lightweight Aggregate Corporation (later shortened to Solite), he negotiated the sale of several hundred acres of the Russell Landing community from one of Clay County’s pioneer families. In the summer of 1959, the plant opened for business, feted in the newspaper for the economic promise it brought to an indigent backwater.

The birth of Solite (the company and the eponymous material) coincided with the greatest construction boom in American history. More than forty million homes and forty-one thousand miles of highways were built between 1945 and 1975. The benefits of Solite relative to heavier, more expensive concrete production were received as a breakthrough on the scale of Romans learning how to make mortar out of volcanic ash and seawater. At the height of operations, there were plants in New York, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Alabama, and Florida. Thirty-two in total. Roberts’s product was everywhere—in highways, high rises, bridges, stadiums, and residences; in landmarks like the Brooklyn Bridge, Lincoln Center, Yankee Stadium, the UN Plaza, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim, the House and Senate chambers of the U.S. Capitol, and D.C.’s Union Station, among countless others. By the time he died in 2016, John Watts Roberts—whose sole remaining plant is still in business today under the banner of Northeast Solite—had transformed the American skyline. The National Ready Mix Concrete Association named its lifetime achievement award after him.

Yet there was another innovation for which Solite became better known, at least for those unlucky souls who shared a property line. The cement aggregate industry depended on fossil fuels for power, but beginning in the late 1960s, price hikes, embargoes, a Gulf War, and a doubling of world oil consumption precipitated a global energy crisis, leaving Solite without an affordable fuel source. At the same time, the U.S. government was flummoxed by the novel problem of hazardous waste management. Pollution began capturing public attention; the Cuyahoga River Fire in Ohio in 1969 was a clarion call for the nascent environmental movement. Richard Nixon federalized the issue, establishing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, which was tasked with crafting and enforcing regulations to meet Congress’s intent for pollution control.

“When Solite first built that place and started mining clay, the EPA didn’t exist, and there were almost no environmental regulations,” Bruce Reynolds told me at a strip-mall coffee shop near his home in Green Cove Springs. He’d worked as an environmental protection specialist with the U.S. Navy, but has since retired, and now he volunteers his time to the Solite Task Force. “Over the years the regulators did, quite frankly, a piss-poor job of going back and retroactively trying to figure out whether or not Solite met their requirements.” Enforcement of new regulations—such as the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) of 1976, which gave the EPA oversight on hazardous waste from the “cradle to grave”—led to steep fines and processing fees for America’s largest hazardous waste generators and relatively poor planning for the lifespan of the waste. In its early years, the EPA permitted Shell Chemical Co., DuPont, Ethyl Corp., and GAF Corp. to dump more than 2.5 million tons of hazardous industrial waste (in blue barrels) into the Gulf of Mexico. This was considered responsible management at the time.

Top: Aerial photograph of Florida Solite from the May 1967 issue of the Clay County Crescent. Courtesy Clay Today/Osteen Media Group. Bottom: Construction of U.S. #1 super highway near Jacksonville, Florida. Courtesy the State Archives of Florida

Solite came forward with a two-pronged solution: Their plants would burn America’s waste in the kilns as fuel, thereby keeping it out of landfills and off the ocean floor, saving waste generators money, and propping up their industry during a period of insolvency. Though severely degraded as sources of energy, materials like spent jet fuel, waste oils, solvents, and acetones still had fractional BTU power and could be blended with clean fuel and fed with the clay to power the kilns. The EPA green-lit the plan and outlined a set of guidelines under RCRA that, years later, became known as the Boilers and Industrial Furnaces (BIF) codes.

“Unfortunately, the enforcement of those regulations was grossly insufficient. We believe that they were burning hazardous waste that they were never permitted under the regulations to burn,” Bruce said. An amendment to RCRA passed in 1980 that opened a wider loophole. Cement kiln plant operators argued that they were burning hazardous waste for fuel, which fell under the EPA’s “beneficial use” category instead of waste disposal. The kiln dust byproduct was explicitly exempted from hazardous waste codes and regulations.

The first time Bruce remembered hearing the name Solite was in the mid-’90s when he still worked as the hazardous waste manager at Naval Air Station Jacksonville. He’d received a phone call from one of his regional managers who wanted to know if NAS JAX had ever sent hazardous waste to the plant in Green Cove Springs for incineration. Bruce checked the ledger and discovered that, in fact, they had, though he wasn’t with the station at the time.

The U.S. military is one of the leading generators of hazmat in the country, and their disposal methods have long been a wellspring of scandal. The catastrophe at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina is a prime example. Marines and their families drank and bathed in high concentrations of contaminated water for over thirty years due to solvents seeping into residential wells. There are over 1,300 active Superfund sites in the U.S.—an EPA term for former landfills and mines in need of extensive remediation—and roughly 130 of them are military bases. (Solite was classified as a Superfund site immediately following its closure but was abruptly removed from the list in 2006.)

Bruce suggested that the lax regulatory environment and the spate of exemptions prompted Solite Florida and its other plants across the Southeast to accept more waste than their facilities could handle and, eventually, to take materials that had little to no BTU value: poisons, corrosives, acids, and even medical waste, a classification that includes dental amalgams, tissue samples, and body parts. At the height of production, they were receiving twenty-five tanker trucks and ten railcars filled with waste each day. The waste was received and handled by a sister company called Oldover, which shared the property with Solite and was the entity permitted by the state of Florida to store the materials. All of it was chopped up, mixed with virgin fuel, and transferred to be burned in the kilns. Not only was Solite getting a fuel source, it was also being paid by the waste generators to take the materials off their hands. As Bruce said, “It got to the point that, in the mid-1980s, [Solite] realized they could make more money burning hazardous waste than making the aggregate.”

The abandoned Solite plant, ca. 2018. Photograph by Aaron Browse. Courtesy the Save Russell Landing/Stop Toxic Solite Facebook group

In the 1980s, residents of Russell Landing started noticing an increasing number of trucks bearing skull-and-crossbones insignias. A chemistry professor from Jacksonville University heard about the operation and warned regulators that cement kilns didn’t get hot enough to completely destroy some of these materials, especially heavy metals, which can’t be fully incinerated due to chemical elements remaining in the bottom ash and fly ash after burning; incineration residue is therefore widely considered to be hazardous waste. The plant was never kitted to adequately capture the dirty exhaust. As a result, he said, toxic chemicals were more than likely being released into the environment through three different channels: There were the particles emitted by the smokestacks, ash and debris dropped from the kilns, and runoff that cooled the aggregate after processing, which bled into the surrounding creeks and lakes. In addition to heavy metals, compounds of dioxins and furans (of Agent Orange notoriety) were alleged to have been present in the exhaust.

The plant burned the heaviest at night to obscure the thick clouds of black smoke. A former employee said he was instructed to “sock” the air-quality monitors around the perimeter of the property so they wouldn’t take readings overnight. Memories of the treetops pulsing in orange and red light and soot left over in the morning have become indelible local lore. Everyone talks about it: seeing their homes and cars and clotheslines saturated in biblical drifts of fly ash. It was mostly thought of as a benign nuisance, something to spray away with a garden hose. It took years to understand the implications.

One of the men responsible for that understanding was Nelson Hellmuth, a solar engineer who moonlighted in the 1990s as a consultant for hazardous waste management and incineration projects in north Florida. He now runs a health-food store out of a home in Orange Park, a quiet former resort town in northeast Clay County. I walked past a display of valerian root and up a set of mahogany stairs to find Nelson upside down on an inversion table. He offered a strangulated greeting before the blood returned to his bare feet and he welcomed me to the chair beside his desk. The house was built in the 1880s, part of a complex of colonial homes that was later used as a primate research facility. Nelson was happy to save it from demolition, as it was one of the last remaining historic buildings on Kingsley Avenue, which took its name from infamous slave trader and American turncoat Zephaniah Kingsley, whose former plantation was nearby.

Nelson’s office was crowded with old wiring harnesses, solar panel prototypes, model airplanes, and New Age literature. A homeowner in Russell Landing had seen his name in a newspaper article after he’d consulted on the high-profile closure of a waste incinerator at a military base in Mayport in the 1980s. He began receiving documents and testimonies in the mail denoting strange health circumstances in the Russell Landing community. “I was probably the only professional engineer that would do all this for free,” he said with a rueful laugh. In time he made his way to the property to investigate. There, he saw the candent glow of the lake (“the ducks were smart enough not to land on it”), noted concentric circles of dead trees around the processing area, and heard from the families of the sick and dying. Of the health surveys conducted in the neighborhood, he said, “The sicknesses in children were off the charts.”

While on site, Nelson had found manifests that tracked the waste stream trickling in from all over the country, documents I thought had been lost or destroyed after 1995. In his office, he stood up, did a grandfatherly back stretch, and walked to the accordion doors of his closet, pulling out cardboard boxes stuffed with brittle yellow papers. He handed me one: Kodak, Revlon, Black & Decker, Sherwin-Williams, General Electric, University of Florida, St. Luke’s Hospital, Jacksonville Naval Station. Dozens of companies sending a combined two million pounds of waste to Green Cove Springs per year. Nelson’s records indicate Sony alone sent 944,860 pounds over an eight-month period in 1994, despite the fact that Clay County had passed an emergency ordinance in 1989 prohibiting the siting and storage of hazardous waste facilities except for waste generated solely within the county. “There were hazardous waste sites around back then, but they cost a lot, and [the companies] didn’t want to pay. So they ended up shipping it here to get burned,” Nelson said.

The Solite railroad bridge on Black Creek.

Apart from the manifests, there were hundreds of pages of environmental reports written by the EPA, the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation (predecessor to the FDEP from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s), and independent investigators describing the fallout. In 1982, the FDER found contamination of public waters in Russell Landing as a result of “industrial discharges” that were “carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic to human beings or […] wildlife or aquatic species.” In 1990, an EPA report noted the possibility of drinking water contamination from groundwater and surface runoff from the scrubber pond. Most of the homes in the region used wells, as did the dairy farms along US-17. By 1991, Nelson had learned that 6,323 pounds of waste per day were being deposited into the scrubber pond. Concurrent sediment testing by the EPA found that the pond contained roughly 50,000 tons of toxic ash: twenty-two heavy metals (many of the same that pinged on Kristen Burke’s most recent testing), PCBs, arsenic levels fourteen times higher and iron one thousand times higher than the legal limit.

In the early ’90s, the EPA concluded that six of the seven aggregate facilities in America burning hazardous waste belonged to Solite, and each one benefitted from the same regulatory exemptions. Buried in Nelson’s closet were manifests from the plants in Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Alabama. Millions of pounds were sent to facilities in these states each year. They all had the same geographical accommodations: railroad access, natural irrigation from rivers and streams, dense forests, sparse populations, and untapped underground reserves of clay and shale. Complaints like those in Green Cove Springs—about the pollution, adverse health effects, and workplace malpractice—had been likewise documented. An employee death in Kentucky, a high probability of dioxins settled in the Ohio River. In the small town of Aquadale, North Carolina, state agencies had tried unsuccessfully for fifteen years to bring the Solite plant into compliance with its toxic discharges, which were reported at 159,887 pounds of heavy metals emitted from its smokestacks annually in “fugitive emissions.” The citizens of Aquadale asked for comprehensive health studies. But despite their county having a higher rate of leukemia and lung, brain, and prostate cancer than the rest of the state, and the country, North Carolina health officials refused to identify Solite’s “industrial pollutants” as a cause.

Nelson became a founding member of a proto–task force in Clay County, alongside representatives from the American Lung Association, Greenpeace, and the Sierra Club. “But I gave all that up over twenty years ago. I would get physically ill at the administrative hearings listening to these professional engineers lying,” he said. “Solite violated environmental regulations almost every year. But [regulators] still wouldn’t shut them down.” He attributed this to the laundering of the company’s reputation in the local chamber of commerce. “And the state was on Solite’s side because they issued them a permit.” The company took out full-page advertisements and wrote editorials in the Clay Today newspaper. The entire town of Green Cove Springs was invited out to the property for Earth Day celebrations and company anniversaries, where Solite handed out free hot dogs and extolled the virtues of hazardous waste incineration. Local schools took field trips there to learn about aggregate production.

After a couple hours poring over the files and searching his own memories, Nelson started to grow despondent. He said he wouldn’t be able to look at the material much longer. When his granddaughter was dropped off at the store after school, he took the opportunity to excuse himself and left me to sort through the rest of the documents on my own.

There was a newspaper article about the closure within Nelson’s records. Early Monday morning in July 1995, local reporter Susan Armstrong stood in front of the Solite gates on assignment with Clay Today. She’d heard that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was planning an inspection of the plant, and she wanted to be there to report on it. By 8 A.M., the dew had burned off, leaving a wilting humidity. But the road was quiet. No grinding machinery or smoke from the furnaces.

“We waited and waited for someone to open the gates,” Susan told me. One of the people waiting with her jumped the fence to see why no one had shown up to work. “When he came back, he said they’d actually pushed the kilns, some of the buildings, and the equipment into the lake,” Susan said. Although Solite would later cite a rise in operational costs as its reason for shutting down, she was convinced its closure was due to the heat from citizen and environmental activism, pending litigation and fines, and a threat from regulators to commence more frequent inspections.

On the Sunday night before their closure, Susan said, “everybody who lived around there said they heard heavy equipment all night, but they didn’t see any of the trucks leaving. Employees told me they were instructed to push everything in [to the lake]. Solite was gone.”

Gone, but not without immediate plans for an encore. The company announced just four months after closing their Florida plant that it was seeking to have the land rezoned for single-family homes. In 1998, the property title was transferred to a shell company called Stoneridge Farms, which shares the same board of directors as Northeast Solite, including chairwoman Joan Roberts Cates, daughter of John Watts Roberts. The Stoneridge Farms gambit was likely an attempt to wipe the name Solite from the public consciousness; yet, with its flaccid evocation of English manor life, Stoneridge Farms also seemed to telegraph a day when the property would be covered in tract homes.

CINDER

A potential connection between the air, water, and soil contamination and Russell’s high rate of illness was first reported in the early 1990s. Prolonged exposure to the contaminants named in Nelson’s reports is known to cause cancer, induce genetic damage, and bind to DNA. Data from the National Cancer Institute and the Florida Department of Health indicates that Clay County has a consistently higher cancer rate than both the state of Florida and the country. The American Lung Association conducted a limited study in 1995 that found the fugitive emissions from Florida Solite contained dioxins and furans, as well as other toxic compounds. That same year, a data scientist from Orange Park compiled survey information and field reporting on public awareness of waste incineration and public health in Russell Landing, but her home was burglarized and the research stolen. There was never a comprehensive, targeted study of the illnesses in Russell Landing, specifically, or of their possible origins. When I asked the Clay County Health Department if they had plans to investigate a high incident rate of cancer, the spokesperson said no, and to contact the Florida Department of Health for more information. When I contacted the Florida Department of Health for more information, the spokesperson said no, and to contact the Clay County Health Department. In lieu of an official tally, Kristen Burke keeps a presentation board with a crudely drawn map of her neighborhood annotated with every person who, to her knowledge, has developed a health problem—cancer, heart disease, immune disease, birth defects—and believes it to be caused by environmental factors. The list includes Burke herself, after a colon cancer diagnosis in 2022.

The Solite plant on May 29, 1995, weeks before its overnight shut down. Photograph by Charlie Strayer, a resident of Russell Landing. CourtesyKristenBurke

There weren’t many people left who’d been there when Solite still operated. One was a past employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity and only if I didn’t betray key biographical details. “Everyone will know who you’re talking about,” he said. We sat outside his trailer in the gloaming as the mosquitoes drained our ankles. It was a stilted conversation. He said he emptied the tanks that came in off the train. “That was pretty much it.” We shook hands and I turned to leave, but before I did, he suggested I try a woman down the street.

I dropped a letter in Debi Spradlin’s mailbox, and Debi sent me an email in response. She’d lived with her husband off County Road 209B since 1984, in a home that backed up to the same lake as the Burkes’. It was clear from the letter that she’d followed the story closely over the years. She wrote about the first time she saw the waste shipments, noticing the smell from the smokestacks morphing into something more acrid, hearing the dump trucks early in the morning throwing fresh dirt on the burials. In the ’90s, she developed two gastrointestinal diseases, which she attributes to Solite, and still receives infusions every six weeks to maintain remission from colon cancer. “I don’t know how many of our wonderful neighbors or children have died due to this contamination, but I am certain the numbers are staggering,” her letter read. Toward the end she recalled an interaction with John Kuiken, a former manager of the plant. “[John] told me personally that there was so much hazardous waste buried in barrels all over Solite property that it would not be habitable in our grandchildren’s, their grandchildren’s, or their grandchildren’s lifetime! Sadly, he passed away from cancer last October.”

I’d heard countless similar testimonies, although a causal relation was virtually impossible to establish at this point. But there were two contemporary and potentially explosive pieces of evidence. When Kristen Burke’s daughter was thirteen, she lost her ability to walk. A CT scan revealed that her hip was deteriorating. It looked like the bone of an eighty-year-old woman. “No one knew why,” Kristen said. She underwent a hip replacement, and when the surgeon removed the femur head, Kristen said, “he told me that’s what heavy metals do to bone.” They hadn’t yet done the soil and water testing in the neighborhood, but a flag was planted by this offhand comment. Two years later, as part of the broader neighborhood testing, samples were taken from the lake behind Kristen’s house, where her daughter swam as a kid. The results turned up barium, cadmium, and lead.

The other piece of evidence came from a woman who left town in 1982 but gave me the single most stirring portrait of Russell Landing I’d heard. Leaving gave Theresa Petty a perspective the others didn’t have. The memories became stronger; the acute sense of joy and heartbreak ensured it would never be a place she could completely leave behind. I spoke with Theresa last June. It had been about a year since a heart transplant narrowly saved her life. “It’s been a long journey, and I’m still going through it,” she said, her speech somewhat garbled. We sat in the living room of her light-filled home along the Matanzas River, an hour east of where she grew up. Her slight frame was swallowed by a floral-print armchair. A diamond crucifix danced around the scar on her sternum.

Her family had lived in a trailer separated from Solite by the lonesome right-of-way for the Atlantic Coast Line railroad. She had two older sisters and one younger brother. They grew vegetables, grazed cattle, dug their own well. “We were always outside,” she said. “Country people. Just country people.” A dozen families had settled around her on adjoining tracts. There was a butcher, a doctor, and a Baptist preacher; descendants of pioneer families who had lived off Confederate pensions; descendants of an enslaved family living in a house made of cornstarch and newspaper; dairy farms as far as the eye could see. The glades were dappled with shallow ponds that formed from the aquifer seeping into forgotten barrow pits. Theresa and the rest of the neighborhood kids treated them like hog wallows. The drinking water was of the same origin. A stream draining from the property irrigated their orange trees. She was describing the 1970s. Excepting modern comforts, it could have been one hundred years before that. The region operated on a kind of frontier economy of limited resources but immense comity. She called it Eden, and you could almost believe her. Until, as she remembers it, the ponds started turning up with mutated, lesion-ridden bass.

“My heart failed when I had my first child,” she said. “The doctor thought it was just the stress of pregnancy.” Her brother, Tony Barber, had been experiencing similar symptoms since leaving the Air Force and returning to north Florida in the mid-’90s—edema in the legs, extreme fatigue—but dismissed these things. His doctor didn’t express much concern either. “I could have saved his life if I had known,” Theresa said. “But in turn he ended up saving mine.” In 1999, Tony went into cardiac arrest and died at their mother’s feet. He was twenty-nine years old. His doctors said it was a freak accident, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, but circumstances pointed elsewhere. Heightened exposures of heavy metals like lead, arsenic, cobalt, and mercury are associated with an increased probability of the condition. (A recent study from the Katanga copper and cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo demonstrated as much.)

Months after Tony died, Theresa went into cardiac arrest again. She’s since had four different defibrillators and lost a child during her second pregnancy. Her youngest son had childhood heart failure (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) but recovered. She believes her sister had an undiagnosed heart condition that led to her passing in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Her surviving sister has a thyroid disorder. There have been myriad health issues throughout her extended family. Theresa maintained that none of this was congenital. “I’ve had a hard life,” she said. “I dealt with it, but I’ve lived in fear every day.”

A partially emerged toxic waste barrel at the abandoned Solite plant, 2023. Photograph by Will Huey. Courtesy the Save Russell Landing/Stop Toxic Solite Facebook group

The fear mounted in the spring of 2023, during her most recent trip to the hospital. She was admitted on March 14th with the understanding that she would not be leaving unless a heart donor came through. The good news came at the end of May. She showed me pictures from inside her hospital room, family crowded around her. In a photo, she smiles lazily, lank hair matted to one side of her face and coursing down her hospital gown.

Between the general exhaustion and dopey medication, it’s been a slow, tenuous road to recovery, but the Florida summer was treating her well. Her old heart is in a refrigerator at the University of Florida research hospital in Gainesville awaiting tissue sampling that could establish a connection between her family’s succession of infirmities and the heavy metals she was likely exposed to as a child. Theresa said the doctors and labs have been reluctant to get involved. “And I haven’t been able to get an attorney to sign a letter of representation.”

These procedures—the handling and testing of tissue samples that could become evidence in a lawsuit—are often stymied by complicated legal preconditions and internal review boards. Not to mention the financial cost. Kristen faces a similar problem with her daughter’s hip. She had the surgeon preserve it for the day that she’ll be able to have it tested. But the sense I got from both Kristen and Theresa was that doctors and surgeons can be averse to testifying in court, if it comes to it, or implicating themselves in what is certain to be a period of bitter litigation. Still, the women haven’t given up hope. “I think that’s pertinent information that we need,” Theresa said. “That’s real proof.”

The task force with Kristen Burke at center, 2018. © Devon Sarian

EDIFICE

One of the most baffling footnotes in this long, ignoble saga has been the response from state and federal environmental agencies. Regulators would file a damning report, “and then the trail went cold,” Bruce Reynolds told me. “In some ways, I think they are almost as culpable as the company.” My experience has been largely consistent. I was invited to send a list of questions to the same external affairs director at the FDEP on two separate occasions six months apart. In each case, I gave detailed reporting notes and a chance to respond to the claims. And in each case, I didn’t get a response.

This lack of transparency was a constant topic of discussion among members of the task force. I joined one of their meetings in late 2023, held at Russell Baptist Church, a sprawling brick campus one mile west of Solite. An icy draft filtered through the open doors, carrying with it the shrieks from a youth basketball game taking place in the church rec center. Bruce peered at some documents over the bridge of his glasses. Next to him was Chad Weeks, the head pastor, and Kristen Burke. Mike Zelinka sat a few rows down, arms folded, bouncing his knee. Fifteen or so residents fiddled on their cell phones. Bruce and Kristen had just returned from Tallahassee where they presented the test results to the FDEP deputy secretary and several officials. “That’s when we sprung the information on them that we had done our own privately funded testing outside property lines,” Bruce said. “Which did surprise them.” But they still didn’t want to commit to a plan for remediation. “The biggest issue is just getting the state to acknowledge the possibility that contaminants migrated from the Solite property and affected people’s health.”

He asked when there would be a resolution to the consent order, which had been opened by the EPA in 1996 and transferred to the FDEP in 2006. They couldn’t jump to conclusions. “The consent order is twenty-five years old. I’m not sure why it’s too soon to conclude what that resolution is going to be.” Plans ranged from a full scrub and removal of all contaminants from the property to signs and fencing restricting access to the most contaminated parts. The former is the most expensive and the most comprehensive, but the state seems to be at least entertaining the latter, which is the plan preferred by Stoneridge Farms. In any event, the cost for remediation would be incurred by whomever purchases the property.

Those in attendance agreed that this was a letdown. Bruce and Kristen wished they had better news. In fact, the news got even worse. A seventy-eight-acre parcel of Stoneridge Farms had sold right under their noses, despite the county commission roundly denying the proposal for rezoning back in 2018. And this new property was now under contract for development with D.R. Horton, America’s largest homebuilder. D.R. Horton would have to work around the county-wide moratorium on rezoning that had been in place since Kristen joined the commission in 2021. Still, the company had bottomless resources and one of the worst environmental and health and safety track records in the country. Standing at the lectern, Bruce brandished a stack of fines the company had received over the last five years. Everything from violations of the Clean Water Act to disability discrimination to dangerous construction defects. “We’ve won a couple of skirmishes, but the war has just begun,” Reynolds said in parting. “We’re going to be dealing with Horton for a long time.” (D.R. Horton did not return a request for comment.)

There was one more thing he wanted to mention in closing: Amid the D.R. Horton sale, Bruce discovered that the Clay County School Board purchased one hundred acres across the street from Stoneridge Farms, less than one hundred feet from where testing had revealed the presence of heavy metals. The task force recommended extensive soil and groundwater testing to the school board. So far, there was no word back.

The attendees were in a lather now. Before the meeting adjourned, the conversation had broadened to an indictment on new development writ large. I realized that their qualms were manifestly bigger than the mere fate of Solite. A reverse migration inland due to overcrowding and inept urban planning of more populous coastal environs had resulted in the destruction of their rural bubble. As more people moved in, longtime residents felt abandoned by the agencies nominally in charge of guarding their way of life. The result was paranoia and cynicism on behalf of the residents, and more terrible city planning on the part of municipal politicians. This is not an uncommon circumstance in Florida. What protects a way of life better than any building codes or planning boards or irate citizens is tradition and a long memory. But we have neither.

Growth-drunk politicians like to remind us that one thousand people are moving to Florida every day. Homes are built on the speculation that this trend will never stop. At the same time, the state, which was one of the hardest hit during the 2008 recession, still has the highest number of vacant homes in America, roughly 1.7 million. This inversion is an effect of “housing starts”—the number of new construction projects that begin in a certain timeframe—serving as a key metric of Florida’s gross state product, and pre-sale developer profit margins being significantly higher in states like Texas and Florida due to lower land costs and favorable zoning laws. A cursory look around town suggests that Green Cove Springs has fully given way to the infernal slog of construction purgatory. Much of this western stretch of Clay County, a former dairy belt, is trapped somewhere in the arc of transformation into a corporate housing development. The prairie grass has been turned over to dirt. All that’s left of the clear-cut forests are thin wooden stakes marking future utility lines.

The new neighborhoods already have grand entry monuments bearing their rustic-sounding names and commercial tags: Cross Creek by D.R. Horton, Lennar at Russell Retreat, Edenbrooke at Hyland Trails by Lennar, White Oak Estates by Richmond Homes, Eagle Crest by D.R. Horton, Kindlewood Forest by D.R. Horton, Oakleaf by D.R. Horton, and my personal favorite Lakes at Bella Lago by Meritage Homes. (The Stoneridge Farms moniker fits neatly into this lexicon.) These names seek to remind us we are out in the country, when the reality is a commercial hallucination of the country devoid of character or history. “These housing ‘products’ represent a triumph of mass merchandising over regional building traditions, of salesmanship over civilization,” writes James Howard Kunstler in his book The Geography of Nowhere. “The places they stand are just different versions of nowhere, because these houses exist in no specific relation to anything except the road and the power cable.”

Eighty percent of everything that has been built in America came in the last fifty years. “Most of it is depressing, brutal, ugly, unhealthy, and spiritually degrading…[t]he whole destructive, wasteful, toxic, agoraphobia-inducing spectacle that politicians proudly call ‘growth.’” Kunstler wrote these lines thirty-two years ago. Difficult to imagine how he might put that today. The 1990s seem quaint by comparison. My own neighbors were still cattle back then.

In addition to poorly designed cities, he trains his polemic on the sprawl of single-family homes in the post-war years, arguing that we are forever chasing the optimism and unmitigated growth of that period. Our built residential environment now resembles a burlesque of suburban ideals. The nature of that growth has been reduced to a simple formula: “Speculation became the primary basis for land distribution—indeed, the commercial transfer of property would become the basis of American land-use planning, which is to say hardly any planning at all. Somebody would buy a large tract of land and subdivide it into smaller parcels at a profit.”

A real estate agent in Green Cove Springs, Helena Cormier, recently pointed out another troubling paradox: There’s never been more housing inventory, but it’s never been more difficult to own a home. “There’s a big cry for affordable housing, but we have affordable housing. It’s just getting swallowed up by investors,” said Cormier. The 2008 recession was driven by sub-prime mortgages; today the trouble is corporate rentals. The “investors” mask their identities through limited liability companies (LLCs), a business structure that offers tax breaks, legal protections, and anonymity. “The LLCs make box offers on hundreds of homes, and then sell them off to another LLC,” Cormier said. “Price manipulation is a natural result of that.”

If you spend enough time on Florida’s division of corporations internet database attempting to track down the identities of shell company owners, you might experience temporary psychosis like I have. The feeling is that of a never-ending game of three-card monte. Corporations like D.R. Horton may be pulling the strings, but I began to notice a pattern, with the same handful of local developers and attorneys shuffling around money and real estate through various LLCs. One of these developers, Michael Danhour, was the man who brokered the sale of the seventy-eight-acre tract of Stoneridge Farms. His business partner controlled a separate, smaller piece of land also purchased from Stoneridge Farms. These were the only two pieces of their property that have changed hands to date.

Danhour and I kept up a limited correspondence for about four months in late 2023 into the spring of 2024. He confirmed that a development license had been sold to D.R. Horton, and that he’d been strategizing with the company as well as “many consultants” on how to get the property build-ready. He told me the best way to ensure proper remediation was to offer developers a path toward purchasing the land and rezoning it for housing. In return, the seller would set aside a portion of the sale price for land remediation, which was the case here. He said $2 million of the $3.3 million purchase price of the D.R. Horton parcel was earmarked for cleaning up the contamination, as stipulated by the FDEP consent order. (Bruce Reynolds has been quick to point out that the $2 million was based on an environmental assessment from twenty years ago, with incomplete testing.) “We’ll be working alongside Stoneridge Farms to accelerate the cleanup efforts,” Danhour said.

There was a precedent here. Thousands of homes in America have been built on remediated Superfund or brownfield sites, usually funded by the federal government. Last year, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provided another $1.5 billion to the EPA’s Brownfields Program, which according to the EPA, transforms “once-polluted, vacant, and abandoned properties into community assets while spurring economic revitalization in underserved communities.” Yet there are estimated to be over nine thousand homes in America within one mile of Superfund sites that haven’t been cleaned up. Most of these homes are publicly subsidized rentals for low-income occupants.

Northeast Solite’s operational plant in Saugerties, New York

In the case of Solite, the land is already selling, but no one can agree on the scope of contamination or to what extent it still poses a threat. The task force has already proved the contamination is worse than anyone thought, but it can’t afford to pay for more testing, and the state won’t assent to it either. There would have to be a tremendous upside to pursue land with these kinds of associated risks. For instance, Danhour pointed me to the billion-dollar First Coast Expressway—the toll road project that everyone in town was complaining about—connecting Jacksonville and St. Augustine with Clay County. “As the Expressway became a reality, it was clear this part of Clay County would be home to a lot of Jacksonville’s population growth,” he wrote in an email, citing a municipal planning document that projects a 25% increase in population by 2040. Stoneridge Farms represents one of the last sizable chunks of land along the expressway corridor in Green Cove Springs that remains unaccounted for. Once the toll road is finished, property values will likely climb even higher. Danhour was aware of this—plus the benefit of the kickbacks from wetland mitigation credits—and he was up to the task.

Danhour eventually stopped responding. So I asked around town for anyone who might have had business dealings with him. From what I could tell, he didn’t have much of a reputation in the area despite his assertion of being a local leader in redevelopment. (But he was involved in a condominium project in Hawaii that’s embroiled in its own scandal.) No one in Green Cove Springs had heard of him before 2018. That was consistent with the other “consultants” I’d identified. No one had heard of any of these people. When I did a tour of the addresses listed on the business licenses of Danhour and his associates, it turned out to be a lot like my internet database search come to life. I found empty storefronts, peeling carpets and upturned furniture, a desk calendar that hadn’t been changed for three months. Buildings that conveyed no affiliation with the world of real estate investment or city planning and consequently had nothing to answer for. Phantoms on paper and in person.

FAULT

Detractors of the task force have implied that its motives smacked of NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard). This was echoed by Albert Galliano, the former plant manager of Florida Solite who now works as an environmental manager for Northeast Solite. During our brief email exchange, Galliano mentioned that, as recently as five years ago, some longtime residents of Green Cove Springs still hunted deer and hogs on that property. In other words, they couldn’t have been too worried about their health. It had crossed my mind: Maybe they just didn’t want any more neighbors, and the whole offensive was a canny articulation of NIMBYism. This was a charge leveled against Kristen Burke and the task force quite often. But, in publicizing the contamination, they were effectively tanking their own property values. This was not in the NIMBY playbook.

Not everyone in Russell Landing was thrilled with the tactics of the task force. In such a small community, there were bound to be a few dustups. Gary Clark lives on ten acres, one of the many residents whose property backs up to Solite, but he took a dim view of the task force initiative. “You have a commissioner who lives at the end of the road, and she is very anti-development because it will affect their generally peaceful area,” Gary said over the phone. In a notable departure from the rest of the neighborhood, he believed that the contamination was “blown out of proportion” and that “most of it is being cleared up by nature,” though he said that he didn’t want to see the property developed until any remaining pollution was addressed.

Gary had particular problems with the STOP TOXIC SOLITE signs installed along the heavily trafficked section of Russell Road, across the street from signs heralding new subdivisions that told a much different kind of story. “The arrows are supposed to be pointing toward a QR [code] where you can get more information. But the way the arrows look, they’re pointing at the new subdivision and people are freaking out [when] they drive by and see ‘Agent Orange.’” He was right. I recalled my initial reaction to seeing these signs. What else are you meant to associate the words “dioxin” and “cyanide” with? Admittedly, the controversy has not been a boon for his work. Gary was a photojournalist with the Florida Times-Union for twenty years before starting a home-inspection company. Now, in semi-retirement, he sells real estate. “It’s a negative selling point,” he said. “They’re hurting the real estate business.”

The person who hammered these signs into the ground had a different opinion. One of the more recent entrants, Randy Gillis moved from Jacksonville to Russell Landing in 2011 with his wife, where they planned to retire. There was an immediate sense that he’d been let in on a secret. We sat outside on his back deck and he held his arms out, invoking the beauty of his surroundings and its relative affordability. “No Realtor said a word when we moved here,” he said. “There were just all these beautiful woods.” Randy was a large man with flush cheeks, a bushy white beard, and china-blue eyes. He was also very sick. In June 2023, his doctor discovered a rare and aggressive form of metastatic prostate cancer. The prognosis was not good, and the chemotherapy made him feel “bad all the time.” His treatment cost around $20,000 a month. He said that his employer had graciously un-retired him so he could qualify for their health insurance, which was a life-saving gesture.

A low creek runs through Randy’s backyard that’s fed by stormwater runoff from Solite, through the same culvert that Kristen had pointed out when we were viewing the burials. “Anytime it rains, we’re getting a fresh dose of that water,” Randy said. If the contamination settled at the headwaters of the creek, “then it’s settled right here too.” He pointed to the sediment at the base of his dock. Not long ago people swam, boated, and ate the fish out of the creek freely. Randy considered the possibility that his cancer was environmental, but as a retired data analyst, he was too pragmatic to say for sure. “But I can’t deny the fact that Don died from cancer, that his wife died from cancer, that the couple right there have cancer. Ms. Pat’s husband died from cancer, on and on and on,” he said, swiveling in his chair and pointing at the homes of his neighbors.

He knew he could gum up the construction machine for only so long. After more than four years of dealing with what he called the “parry and thrust” of Danhour and the developers, his greatest frustrations lie with the FDEP, the EPA, and the county. “There’s a set of facts that seem puzzling for groups whose charter is to protect the health and welfare of its citizens,” he said. “Where’s the protection?” He was likewise puzzled by the lack of accountability from real estate agents. Randy considered it the responsibility of both sellers and sales agents to make crucial disclosures about potential contamination. Short of that, he had to take matters into his own hands. One of Randy’s neighbors tried to sell his home during the initial development proposal and rezoning hearings in 2018. It was one of the pricier houses in the neighborhood, on a point of land with generous canal frontage. The seller had a deal in hand when Randy put one of the infamous signs up at a nearby intersection. The buyer saw it and backed out. Randy had little remorse when the neighbor confronted him. “That’s your Realtor’s problem. That’s your problem,” he said.

CONDUIT

The community has been looking for incontrovertible proof of malfeasance for over three decades. And for just as long it has eluded them. In truth, thirty years of erosion caused by subtropical wind and rain, the maturation of pine tree plantings, and the rewilding of upland marshes have all done a number on the principal evidence.

Even when proof was seemingly within reach—most recently with the test results—that hasn’t been enough. One of the only times anyone had seen state regulators in person was on the property of Ben Gesell, who purchased a small clapboard home in Russell Landing in 2022—the one closest to the main entrance of the plant that I’d passed a dozen times. Soil samples were taken from his property in 2023, and there was a positive hit for cadmium, chromium, and lead. One morning last spring, he found two FDEP inspectors poking around his front yard, thinking that he wasn’t home. When confronted they admitted to being ordered to investigate the testing site and, as Ben remembered it, said the results didn’t matter because “you can get cancer from all sorts of things.” A deputy secretary of the FDEP later called him to apologize for state agents trespassing in his yard. She asked if he wanted to press charges. He said no; he just wanted them to do their job.

Nevertheless, the search for proof was what brought me to the mouth of Black Creek and the St. Johns River last Labor Day weekend, where Harold Burke was idling his flats boat after a bad storm. He doffed his sweat-ringed visor to welcome me aboard. Harold works as a charter fisherman, and we were motoring out to examine the back half of the Solite property from the water. Harold and Kristen had been out on a joyride late that summer when they noticed a stream they’d never seen before running off the property and draining into Black Creek. In its latest correspondence, the FDEP avoided questions about a culvert or a separate diversion from the scrubber pond—“the nightlight”—that would allow contaminated water to flow out to public waters, but former employees claimed a ditch had been dug years ago on the east side of the railroad bed to prevent the tracks from flooding. The existence of this stream, coupled with new evidence from the creek behind Randy’s house, would puncture the state’s argument about containment. In short, it was another potential breakthrough.

As we passed through the shadow of the Highway 17 bridge, Harold remembered this channel being a toxic stew back in the day. I’d found a corroborating report in Nelson’s closet. There were at least six documented breaches of contaminated water caused by storms during Solite’s tenure. Hundreds of diseased and mutated fish were gathered by a local organization aptly titled C.R.A.P. (Citizens Reaction Against Pollution) and given to a chemistry professor at Jacksonville University. Dr. David Neal Boehnke concluded that the fish contained “excessive amounts of heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and PCBs” in his findings, which were presented to the FDER in 1992. He also remarked on a legacy of noncompliance with emergency monitoring and permit regulations and implored the state to conduct a comprehensive groundwater study, which never came.

Harold brought the boat on plane and slalomed through the creek. The water on the surface was blacker than fresh asphalt but splashed crimson in the wake. The banks were lined with lily pads and armored gator spines, pine trees listing diagonally above them. A mohawked kingfisher followed us close behind. Harold had a lilting, boyish laugh and a great affinity for the creek. It was deep for its size, he said, up to sixty feet in some places, and it once gave naval ships safe harbor during hurricanes. The creek basin encompasses most of the county and has always been the center of life in this part of the world—plied by Native Americans, early Spanish ironists (who called it the Rio Blanco), slave traders, Union soldiers, and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Harold pointed out the dock of Ronnie Van Zant and Allen Collins’s red tin-roofed rehearsal space, nicknamed Hell House, where they fished, trapped gators, and composed “Free Bird” when they were still in their teens. The cover art of their third album shows the band members perched on a railroad trestle above the creek, right before the tracks disappear into Solite.

“I’ve been out here on this water since I was eight years old,” Harold said. “They were burning so bad you couldn’t see out of your windows at night. You wake up in the morning and it looks like you live next to a volcano.” He slowed as we approached the banks of his neighborhood and cut the engine as we crossed over the invisible line separating Russell Landing from Solite. The northern half of the property was all wetlands that sloped gradually down toward the creek. “It’s all chewed up and grown over now,” he said. The shoreline runs for nearly a mile in a tangled mess of oak and cypress. Aside from the scant indications of human contact—like the line of rotting pilings where boats used to tie off—the landscape was raw, impenetrable bayou. Hard to imagine it bending to the greige monotony of a housing development.

“Here it is,” Harold said, motioning toward a cleft in the hard-packed shore. “Now tell me why there isn’t nothing growing in that?” He nosed us into the stream, and we could see there was nothing to see—no signs of life that were otherwise abundant along the way, only the slow churn of water. “And you know what you won’t catch in there? No fish,” he said. “Tell [F]DEP that—just go test. What makes you so mad is how much they drag their feet.”

In a recent email, the FDEP implied that they wouldn’t have jurisdiction over the water bodies on private land; therefore, the waterway was not theirs to test. “For the purposes of investigation, I’m at a loss for why that matters,” Bruce had said weeks earlier. “It sounds like a stall tactic.”

Regulators appeared to have no record of this stream, and it was not on GPS maps. Yet here we were, gawking at it. Harold and I took our time examining the water from different angles and noting the industrial detritus that lined the banks—a broken apart dock and what looked like the open maw of a blackened storm drain, or maybe it was a burial, Harold said, shrugging. After, he piloted us back to the marina in silence. It was by and large a successful trip, but the task force still needed to pinpoint the source of the diversion on the property itself to build their case.

SHIELD

Harold and Bruce had arranged to meet at the Solite gates the following morning to locate and photograph the headwaters of the diversion with a drone, but later that night it started raining and didn’t stop for two days. I repaired to my hotel room at the Club Continental, a moldering Gilded Age palace on the banks of the St. Johns River—and former winter home of the heir to Palmolive soap—that was long past its prime. I waited out the storm reading a book John Watts Roberts had written and self-published in 2011: a biography of his late wife, Jane, who had died a year earlier. It blended tender recollections of their seventy-year marriage with a dry corporate history of Solite to the extent that it felt like an elegy for both. He gave Jane credit for encouraging him to become a leader in the “hazardous waste business,” accounting for “22 percent of the nation’s volume that was beneficially burned.” In 1987, the couple are pictured at the Green Cove Springs plant celebrating the forty-year anniversary of the company before decamping to Miami for stone crabs and a performance by Dolly Parton. In 2002, the same year environmental and citizen groups filed air quality petitions with the EPA against the Virginia plant, Roberts writes about his stockholder meeting at a seaside resort in Maryland where the “soft-shell crabs were stacked 18-inches high on the buffet table.”

Entrance to Northeast Solite, Saugerties, New York

John and Jane traveled the world together indulging strange whims. “In our early 60s we decided to take up a sport together and we chose hot air ballooning. We ballooned from Vézelay and Beaune in the Burgundy country. What a life—sightseeing in the morning—having a relaxing lunch—ballooning and chasing in the afternoon—dinner served in imaginative places such as on a Roman bridge or a castle courtyard.” But his greatest passion, aside from his wife and business, appeared to be volcanoes. He tracked them all over the world: Sicily, Iceland, Costa Rica, Hawaii. “Volcanoes were magnets,” he writes. “The heat emanating from the lava flow, the flames at night that acted as beacons, and the plumes of dust told us that the earth is a living entity put here by God for those who followed Adam and Eve to use and enjoy.” He recalls crisscrossing the Carolina Slate Belt hundreds of times, tapping the metamorphic rock that had formed there as a result of ash spewed from ancient Archean volcanoes. “The sulfur and pyrites included in the ash cause the slate to expand when heated in a rotary kiln to the point of incipient fusion. Jane and I studied the best locations to build a plant as we traversed the slate belt.”

God made earth, earth made stone, stone made Solite. This type of natural resource dominionism pervaded John’s book. It was part of a continuum of economic extraction that, in places like Green Cove Springs, began with logging and turpentine, transitioned to clay, and for its final act belched another odious suburb onto the earth’s surface. John tied his own mythology to the divine creation of all things. In that sense the volcano obsession didn’t really stand apart from his wife or his business. They were all one. I don’t know if he always felt this way, or if it was something that came during these late moments of nostalgia and grief, but he showed no indication of having anything but a spotless conscience. And that was why he evangelized his creation so thoroughly. Look at what I gave us, the book said over and over. Look at all these buildings.

On the morning the rain had cleared, I checked my phone and saw that we were ready for flight. I walked out on the lawn, which seemed to have grown a foot in the last twenty-four hours, and watched as the sun lit up the Palladian windows of the lobby. At least the grounds of the hotel still held a feeble charm. The wife of the quarterback of the Jacksonville Jaguars was in the dining room with a hive of her friends decorating for a Downton Abbey–themed luncheon as I ate my continental breakfast. A waitress pointed this out sotto voce. “I think the Jaguars’ stadium was built with clay mined a few miles from here,” I said in response. I was beginning to think like John. This was news to her, and she politely feigned interest.

I drove to meet Harold, Bruce, and the drone operator, who turned out to be Pastor Chad Weeks of Russell Baptist Church. The pastor comes from a long line of Clay Countians; his children are sixth generation. His family lives on twenty acres across from the church. By his lights, they are the last family to still graze cattle on his road. He has no intention of selling, though the encroachment of subdivisions has made things uncomfortable. “We’re literally surrounded on all sides,” he said.

Harold was a no-show. “Should we get started without him?” Bruce asked. Pastor Weeks shrugged and got the bird in flight. He had a rough idea of where to find the diversion and set the coordinates, watching the tree line and negotiating a cell tower that had already cost the neighborhood two remote-control drones.

After the whir of its tiny plastic propellors abated we heard a vehicle creeping down 209A. “Must be Harold,” Bruce said without turning to look. But it wasn’t Harold. It was a CSX railroad employee in a white truck who drove right past us and stopped in front of the entrance. He climbed out and gave a quick nod in our direction, unlocked the heavy chains, and secured the gates behind him once he’d pulled through to the other side. Bruce suspected he was going out to service a signal box. The three of us traded glances, unable to hide the minor embarrassment in watching someone waltz onto the property when we were still stuck outside trying to get a bead on the place. But most of all I was jealous. I’d spent over a year returning to where this spalling county road met with hard-packed mud and the forest began, listening to stories of what lies on the other side of the gates, and this dude was getting it all to himself.

Pastor Weeks shook me from the trance. He’d located something, but his remote was cutting out, which caused him to spurt a few minced oaths.

“Don’t sacrifice your drone,” Bruce said warily.

“I’m just going to snap a couple photos,” Pastor Weeks said, the electronic shutter firing a burst of images. He barked orders: “Stop, stop”; and then, “Please, no”; and then a dejected, “We lost signal.” A minute later the drone appeared above the trees, flying homeward and, to the pastor’s great relief, landing gingerly on its launchpad. We crowded around his cell phone as the images loaded. They showed the scrubber pond diversion and streams that ran along both the east and west sides of the railroad.

“Oh, that’s perfect” Bruce said. “That’s absolutely perfect.”

As of this writing, it has been five months since our flight. Bruce delivered the images and data collected on the diversion to the FDEP in October and was greeted with silence, but the property has not been quiet. Residents spotted a Bobcat being trailered through the gates of the property early one Sunday morning in December. Not long after, Brent White (a local developer with ties to Danhour who purchased the smaller parcel from Stoneridge Farms in 2022 via his LLC and whose Potemkin storefront I’d visited earlier in the year to no avail) was seen exiting the main entrance of Solite frocked in Mossy Oak gear and toting rifle cases. Hours later he posted a photo on his Facebook page of a preteen boy, presumably his son, in the woods doing the buck pose with a four-point yearling. Florida law stipulates that a lease is required for hunting on private property, and leases are a matter of public record. The entity in charge of licensure—the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission—has no record of any active hunting lease for the Stoneridge Farms property.

The most recent entries in the public information portal on the FDEP website show correspondence between Albert Galliano, the geoscience engineering firm Stoneridge Farms hired to advocate on its behalf, and state functionaries. But there was no resolution here. Only Stoneridge Farms, via its proxy, requesting “no further action” to be taken on three “areas of concern” within the property and Bruce Reynolds writing back to tell them that was unacceptable, providing various dryly convincing reasons why.