“In the Kitchen with Celia” & “For Me: A Sweetelle”

New poems from the Food Issue

By Sean Hill

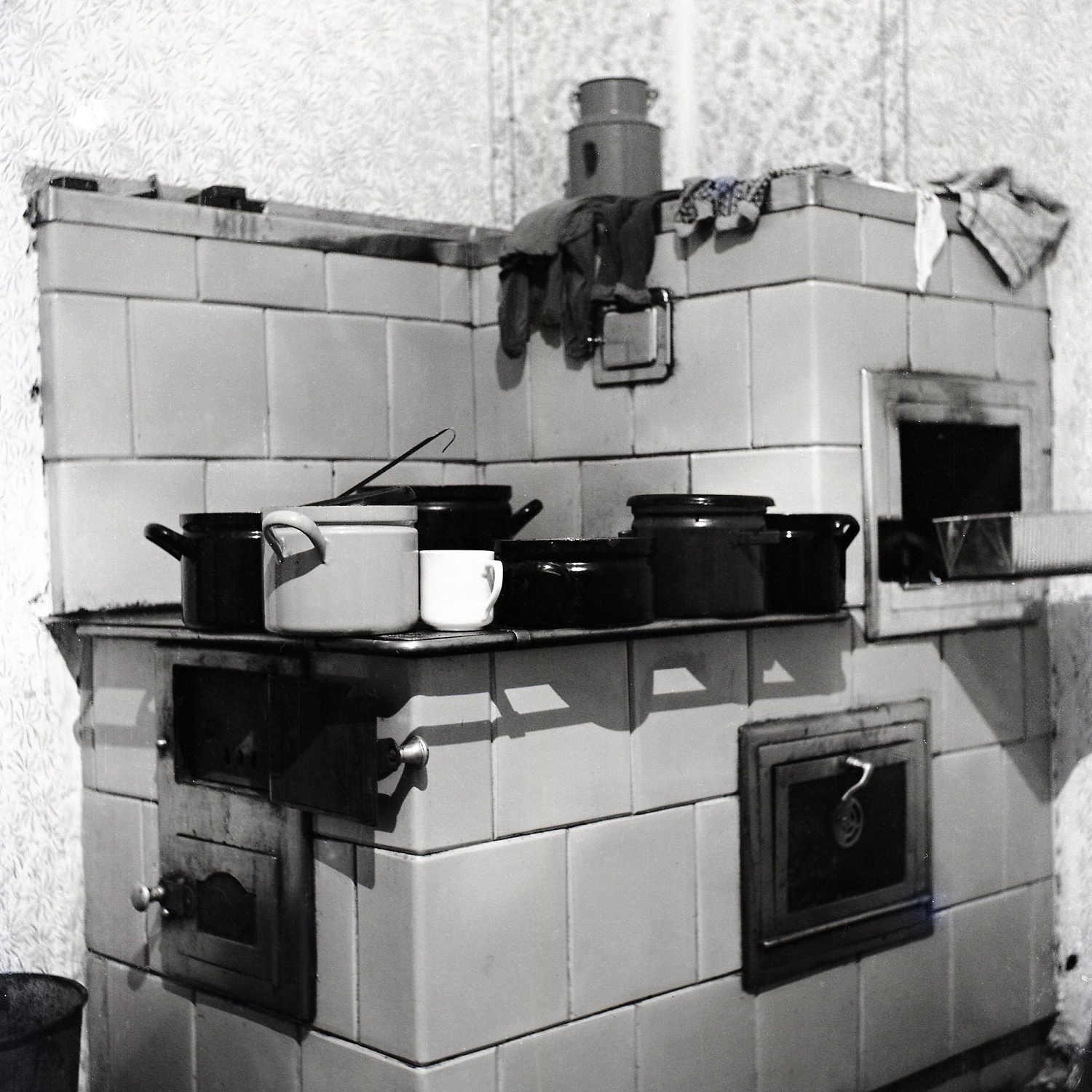

© Jasiok K. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

IN THE KITCHEN WITH CELIA

The kitchen her domain, a hot continent

of her own as much as can be, as long as

she keeps the house, the Browns, well-fed.

——

kettle

hooks for hanging things

rod

Dutch oven

cannisters

table

sifter, mixing bowls, and measuring spoons & cups,

whisk

knives, forks, spoons, the dinner service

bread box

patterned oilcloth

cutting board

flyswatter, dustpan, and broom

ash bucket and shovel next to the wood

spit in the hearth

dumbwaiter to serve the rest of the house

butter churn with dasher for the clabber

grinder

larder

——

Some kitchen objects have handles worn smooth by hands, an incidental rubbing with sweat and oils, and pots and pans carry seasoning (contain processes and eventualities—kitchen memories) and their heft has weight, can transport us with a touch or a taste of the food from them. Objects bear witness to kitchen witnesses—cooks.

——

I wonder what Celia makes of that man

from Macon come here to bake when

company, what they call a State gathering,

demands. They love his specialty, Apples à la

Parisienne. I wonder what Celia makes of that

Mister Freeman, that Negro and his freedom.

I wonder if Celia sees herself as governor-fueler,

greasing the machine, though her food nourishes

this politician up to and through what they’ll

call a rebellion to keep to their ways including

foremost the holding of Celia and vast hosts of

Negroes and their generations to come in bondage.

I wonder what Celia thinks about the fact

that Governor Brown would rather have her

cook shad pulled fresh from the Oconee at

the end of Jim’s cane pole or something Jim

shot in the woods around with his flintlock than

any of the fancy dishes she makes for their levees.

I wonder what she prefers to cook and what dish

her dear Emma most desires from this kitchen.

——

I see Celia in line with other Black cooks; some we know like Hercules Posey, held by Washington—sent back and forth from Mount Vernon to Philadelphia—from slave-holding state to free and back again to keep him according to the laws and to keep him cooking, and Jefferson’s chef, James, James Hemings, Sally’s brother, whom TJ took to France to be trained. James, he brought back macaroni and cheese for the president and now it’s for the people. James had to train his brother to take his place before he could leave the place, Monticello. Zephyr Wright was LBJ’s cook at the White House and before that when he was a representative, and she had his ear and told it like it was for her and hers. And before that and after the war Malinda Russell published A Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen in 1866, the first cookbook known to be written by a Negro woman. In 1881 Abby Fisher, another Negro woman, published the second known Black-woman-authored cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. This is what we know and what we got receipts for. Negroes learned to cook where they did. Most in the quarters, many in the plantation kitchens, in the mansion, some at home, some in college, a few in France now—many putting they foot in it like my grandma and aunties, reminding us to put okra in the stew if you know what’s good for you. Cooks—the hands and hearts that make the food—tell of journeys, hold our heritage, and bear witness. I’m grateful for what receipts we got and for what we know.

——

A Negro cook’s recipe for

Freedom in the Slave-holding

South calls for 1 very first

breath and 1 pinch of the

independence we’ve all

at one moment felt and ½

mindful of the ancestors’

struggles and 1 heavy needful

of respect for the Negroes’

bodies & loves and ½ a playful

of leavening care and 1 runaway

returned (you, a loved one,

someone new to the place,

or a story told of one whose

decisions and actions open

a space to consider questions

of home) and 1 last breath

(preferably not your own)

and 1 heaping joyful of

the ability to go see your

people and not have to rely

on the person who claims

to own you to relate your love

to your friends and kin (this

last is optional). Season to taste.

FOR ME: A SWEETELLE

After Allison Joseph

For me the struggle was the pig; it’s spelled P-O-R-K

but sounds real close to “poke” in my mother tongue (mother’s

mouth) like what you might put something precious in like a pig.

I forsook the toothsome sweet hell flesh for health decades ago.

For me the struggle’s still the pig; it’s spelled P-O-R-K

and seems to be the favorite meat of my home—Georgia.

I’ve moved to Alaska, sat at the Thanksgiving table

of a man who’d raised a pig, and gratefully eaten his ham

—twenty years’ memory seasoned that savored sweet hell flesh.

For me the struggle is the pig; it’s spelled P-O-R-K.