Lena Richard’s New Orleans Cookbook

A portrait of America’s first Black cooking show host

By Mayukh Sen

Collage by Carter/Reddy

One night, the chef Lena Richard dreamt of fruit.

She pictured a dessert fashioned in the likeness of a watermelon, only one that you could eat “clean through the rind,” as she told the Times-Picayune in 1938. When she awoke, she actualized her vision: She blanketed the bottom of a crescent-shaped mold with whipped cream—the lower half tinted with green food dye, the upper half white—to simulate the fruit’s rind. She then ladled three cups of ruby-red strawberry sherbert into the mold, bespangling it with raisins meant to represent the seeds, before piling the mixture with two more cups of sherbert. (She considered, for a moment, either chocolate chips or prunes in lieu of raisins, but neither felt right.) After hours over a bed of ice and salt, it set. What emerged was a confection that Richard dubbed her “dream melon.”

That dream melon became one of the signature dishes Richard served at her catering gigs for wealthy white socialites throughout the 1930s in New Orleans, the city where she’d spent the majority of her life, a Black woman working against the segregative realities of Jim Crow. It was a time when the watermelon was the subject of nasty racist caricatures, weaponized by white folk to malign her people.

Such was Richard’s genius: She could take a food so symbolically charged, stained with prejudice, and find authorial agency in it. That dream melon wasn’t just a dessert; it was a reclamation.

You could consider that dessert a precis for Richard’s culinary career, one she spent working across registers—running food businesses, teaching, writing a cookbook, and even hosting her own television show—while negotiating the demands of both Black and white audiences. Before Leah Chase was nourishing heads of state at Dooky Chase’s; before the likes of Paul Prudhomme, Justin Wilson, and Kevin Belton were spreading the gospel of New Orleans cooking on public television; and long before Nina Compton parlayed a stint on Top Chef to opening renowned restaurants in the city, Lena Richard was perhaps New Orleans cuisine’s most prominent ambassador.

WDSU filming Lena Richard. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy Lena Richard papers (NA-071), Newcomb Archives and Nadine Robbert Vorhoff Collection, Newcomb Institute, Tulane University

The question of where and when, precisely, Marie Aurina (later Anglicized as Lena Marie) Paul was even born remains a matter of dispute. Baptismal records, census documents, Social Security applications, and her autobiographical statements often tell conflicting stories. Dr. Ashley Rose Young, a scholar who is co-authoring a book on Richard with Richard’s granddaughter, Dr. Paula Rhodes, explained this to me.

“That’s not uncommon when you’re studying the history of people born in the late nineteenth century or early twentieth century,” Young said of the discrepancies. This was especially true of rural communities. “One just has to be comfortable with ambiguity.”

Census records suggest she may have been born in New Roads, Louisiana, hours outside New Orleans, in 1892 or 1893 to Francoise Laurent (Frances Laurence) Paul and Jean Pierre (John Peter) Paul. Hers was a large family, though many of her siblings passed away young. Richard herself would contradict her widely accepted birthplace in a two-page autobiographical sketch she wrote in 1944, wherein she claimed she’d been born in New Orleans; she would sometimes even say that she was born in 1900, which may very well have been a self-mythologizing embellishment she used to maneuver the barriers of the era—especially in a time when the domestic service industry “often portrayed Black women as motherly or grandmotherly figures,” Young said. The decision to sometimes label her birthplace as New Orleans, Young suspects, may have been a survival tactic, too, in a period “when some in the city were quite xenophobic and suspicious of people born in other parts of the country.” No matter the reasoning, Richard’s potential obfuscations may also have signaled the power she found in telling her story on her own terms, when structural forces otherwise stymied Black women.

What is certain, per census records, is that by 1910, she was living in New Orleans with her family. There, her mother was in the employ of white families as a cook, a vocation common for Black women of the era, whose employment options were limited by Jim Crow. Richard’s earliest culinary education came at her mother’s side, and by the time she turned fourteen, she had taken on cooking duties herself. She began working for an elite white woman named Alice Baldwin Vairin. (The archival record is, again, contradictory here: Some sources state her mother had been working for Vairin all along, while Richard’s own writings maintain that a cousin of hers worked for Vairin.)

No matter how the job fell in her lap, Richard relished this work. She started out by working for Vairin before and after school, preparing her children’s lunches. Her responsibilities incrementally increased with each passing year until she turned nineteen and the family’s hired cook left. They asked Richard if she’d want to make meals for their family of seven. Richard said yes. Her initial salary was $10 a month, around $300 today.

“Mrs. Vairin was amazed that I could prepare such good food since I was so small,” Richard would later write, referencing her wiry, ninety-nine-pound frame. She and Vairin forged a relationship that was, by most accounts, highly copacetic. Vairin, an avid cook herself, encouraged Richard to hone her culinary voice, giving her carte blanche over shopping and menu conception. “I got chicken, made stew and had fruit for dessert,” Richard recounted in writing. Vairin was so pleased with Richard’s work that she soon raised her pay to $15 a month (just under $500 in today’s dollars). Vairin then let her buy whatever cooking utensils she wanted, also allowing her a day off each week to pore over cookbooks and test new recipes. She offered to give her cooking lessons and send her to demonstrations, even schools—all of which Richard took advantage of enthusiastically.

“If no other colored women could get places I certainly could,” Richard wrote. If this may seem like a point of tension for Richard—who would later publicly uplift her fellow Black chefs while still interfacing with white audiences—the question of how she felt about such contradictions is not one that the archive can easily answer, Young said.

“My gut instinct is to say that she likely always felt compelled to help other African Americans in the domestic service and food industries,” Young said. She added that Richard had come of age in a culture where there was “an informal apprenticeship among Black women in kitchen spaces,” meaning she may very well have recruited neighbors and friends to assist her in various endeavors. She seemed aware that such material support like the kind Vairin gave her was rare, and far removed from what other Black women would have experienced in her time. Richard certainly knew that such patronage from white folks could help expand her possibilities in an otherwise hostile era.

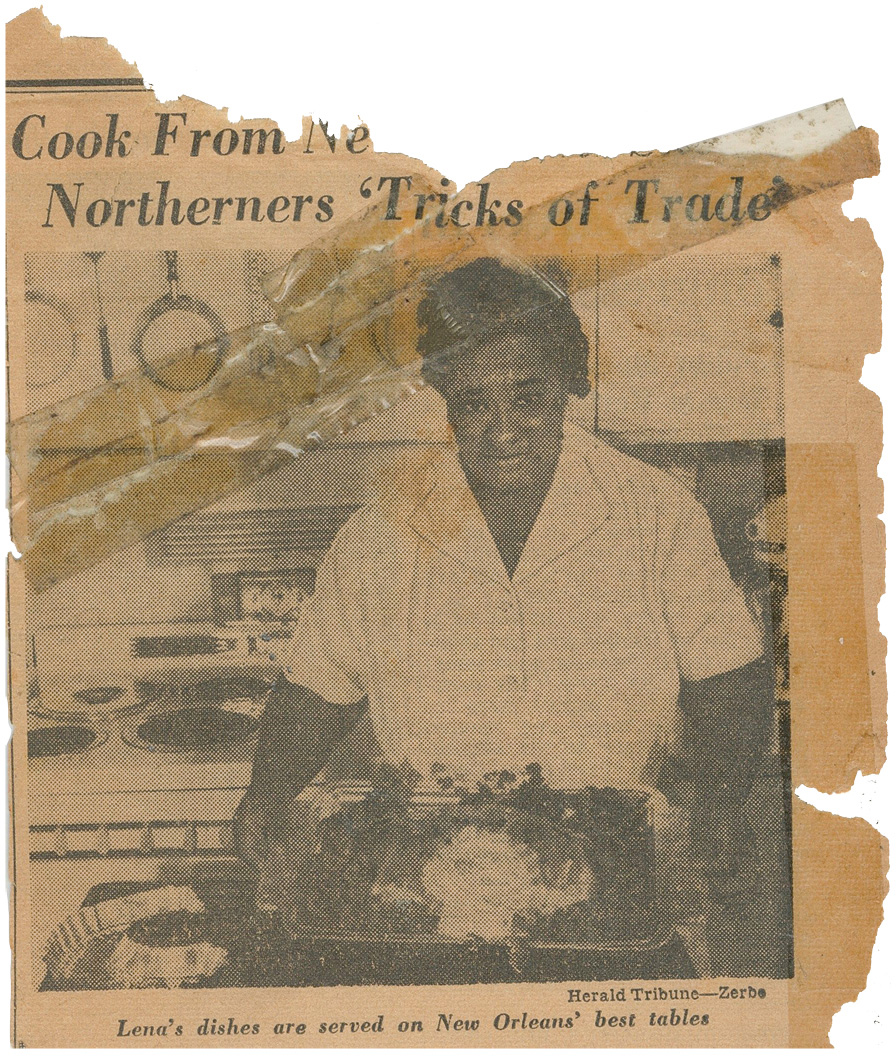

Clementine Paddleford article on Lena Richard from the New York Herald Tribune, 1939.

By the time Richard was around twenty, she had honed her culinary voice considerably with those stews and fruit desserts she made for her employer. Vairin encouraged the young woman to trek to Boston to attend the prestigious Fannie Farmer Cooking School, promising to bankroll Richard’s studies there. For a Black woman to attend a cooking school up North was “extremely rare,” said Theresa McCulla, author of Insatiable City: Food and Race in New Orleans (2024). (Jefferson Evans, widely considered to be the first Black American to graduate from the Culinary Institute of America, did so in 1947—a full generation after Richard’s education at the Fannie Farmer Cooking School.)

Richard knew that her education at Fannie Farmer would give her credibility in the eyes of a wealthy, overwhelmingly white food establishment. But she soon found that the racial hierarchy that governed her life in the South was reified up North with de facto segregation. To start, Richard had to obtain written permission from each of her white classmates to even participate in the school. She also had to eat meals in a separate room.

“This was a time when Black Americans were purposefully exiting domestic service,” McCulla explained. “They were trying to leave kitchen work behind rather than trying to train professionally for kitchen work. And so because of this, many white Americans were going to culinary schools, and they were publishing cookbooks in order to prepare recipes that had previously been prepared for them by enslaved or free Black chefs or cooks.” Such titles included the first edition of Picayune’s Creole Cook Book (1900), whose collective of white authors “recognized the skill of Black women kitchen workers but acknowledged their knowledge to be oral and therefore perishable,” as McCulla put it. The text itself expressed the authors’ imperative to document recipes “from the lips of the old Creole Negro cooks and the grand old housekeepers who still survive, ere they, too, pass away, and Creole cookery, with all its delightful combinations and possibilities, will have become a lost art.” Implicit was the racist notion that Black cooks did not have the intelligence to write down these recipes themselves.

Despite the structural impediments she faced, Richard found her eight-week coursework at Fannie Farmer a proverbial breeze. “But when I got ’way up there, I found out in a hurry they can’t teach me much more than I know,” she later recalled. Sure, she confessed, the experience opened a world of new desserts and salads to her. “But when it comes to cooking meats, stews, soups, sauces and such dishes we Southern cooks have Northern cooks beat a mile,” she boasted. “That’s not big talk; that’s honest truth.”

Classmates were enamored of her thick Creole gumbo and her chicken vol-au-vent, the bird encased in a round puff pastry. These dishes conjured her upbringing in New Orleans. The response was an early sign that Richard possessed an interlocutor’s gift to reach others far more privileged than her, and to tell them who she was, through her food. The other students scribbled down her recipe instructions with such fury that Richard wondered if they’d gone crazy.

“I think maybe I’m pretty good, so some day I’d write down myself,” she later recalled of her thinking at that moment. Richard began to ask herself if she had a cookbook in her, though it would take some time for her to answer that question.

Lena Richard’s Gumbo House.

Little documentation attests to the years following Richard’s studies at the Fannie Farmer Cooking School, after which she returned to New Orleans and continued working for the Vairins. It was through word of mouth that Richard began to build a reputation for herself amongst elite New Orleans families as not just a reliable cook but an extraordinary one. She began a catering business around this period, too—primarily serving white high society—adjunct to her work with the Vairins.

We do know that she wed a man named Percival Richard in 1914, and that, seven years later, she gave birth to her only child, Marie. Richard asserted, in her own autobiographical statement, that she had struck out on her own by the time she turned twenty-eight, leaving the employ of the Vairins. She opened an eatery called the Sweet Shop, selling sandwiches, red beans and rice, and watermelon salad. Because Richard ran the Sweet Shop out of her home, Young surmises that her clientele would primarily have been Black, far different from the demographic who patronized her catering business, thus evincing Richard’s growing ability to navigate two racial milieux. By 1930, during the Great Depression, census references suggest that she even enjoyed employment as a teacher, possibly as a home economics instructor at a Black public school in New Orleans.

The frequency of records picks back up around 1931, when Richard experienced the death of her former employer, Alice Vairin. Though little archival evidence can tell us how she processed this news emotionally, she would retain a fondness for Vairin that stood the test of time. Her relationship with the family would continue even after the death of its matriarch, and she would lean on them for support when necessary while walking her own path.

By this point, Richard’s catering business was in full bloom, buoyed by the reputation for excellence she had crafted among New Orleans’s white socialites. That same year, 1931, she was named head chef of the Orleans Club, a swanky social circle then populated by white women. Her work at the organization involved preparing food for luncheons: Think straightforward potato or crab salads. The network there expanded her audience, and she began to field requests for even more catering gigs, which she found provided her greater artistic latitude than her rote work at the club itself.

By 1936, however, Richard’s focus shifted. She began hosting large-scale cooking demonstrations for all-Black audiences. A year later, she left her post at the Orleans Club and opened the Lena M. Richard Catering School—the first cooking school operated by a Black woman in New Orleans, and explicitly for Black men and women.

“My purpose in opening a cooking school was to teach men and women the art of food preparation and serving in order that they would become capable of preparing and serving food for any occasion and also that they might be in a position to demand higher wages,” Richard would later write. The school’s rigor was intentionally meant to match that of the Fannie Farmer Cooking School. Students would attend lectures and classes and, if their work was deemed satisfactory, obtain a diploma that celebrated their competence “in the Art of Plain and Fancy Cooking.”

But Richard continued to interact with white audiences, too, in this period. One of the Vairin daughters helped Richard mount an analogous school for white housewives. She would also conduct similar demonstrations for white audiences, who would cart home samples in limousines. By this point, Richard was straddling two distinct racial universes, Black and white, at a more public level than ever before in her career. Young, the historian, told me that she has found little in her research about how Richard felt about walking this particular tightrope. “But I think it is pretty clear that she was savvy enough to navigate both worlds successfully and that she remained committed to providing African Americans very similar opportunities to whites,” Young said.

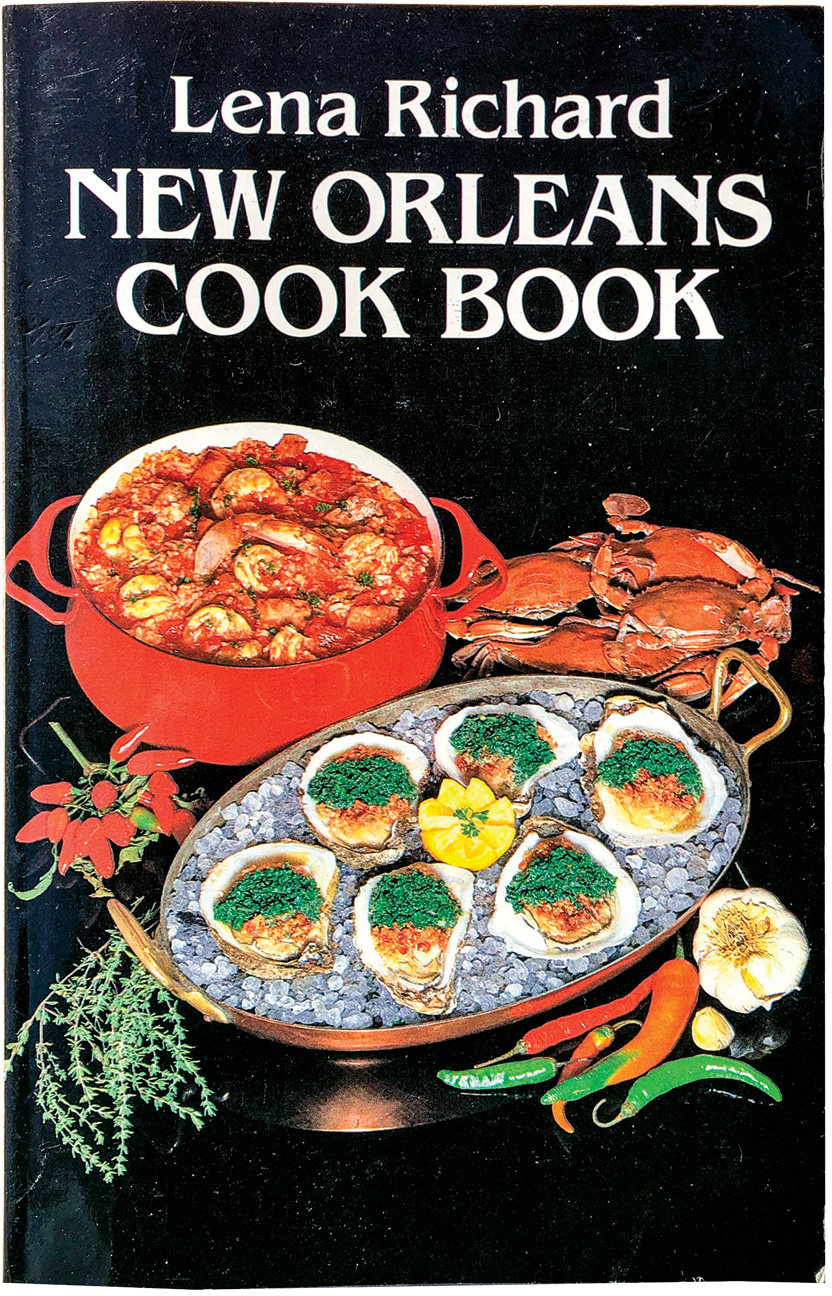

Meanwhile, Richard had also been working to realize her dream of writing a cookbook, an idea that had been gestating since her Fannie Farmer days. With the help of her daughter, Marie, she spent two years and one month compiling the self-published Lena Richard’s Cook Book, which she sent to the printer in 1939. Richard felt so passionate about seeing this project through that she sunk into debt to the tune of $1,200, what would be just over $27,000 in today’s dollars.

Lena Richard’s Cook Book broke barriers, as Creole cookbooks prior had been the domain of white authors. The trend from an earlier era of white New Orleanians anointing themselves the stewards of the city’s Black culinary knowledge—premised on the belief that Black cooks were illiterate and therefore incapable of transcribing their own expertise—had continued well into Richard’s adulthood. The white writer Natalie V. Scott’s Mirations and Miracles of Mandy (1929) trafficked in stereotypes about Black women. Even the title reflected this racist condescension, as Scott would write that the “Mandy” in the book’s name was “a composite” of Black domestic workers employed by white women like herself: “My own Mandy’s name is Pearl,” she wrote. “There are the Mandys of all my friends—Mammy Lou, and Phrosine, and Tante Celeste, Venida, Felicie, Mande, Titine, Elvy, Mona, Relie.”

Richard’s cookbook was a forceful riposte against such currents in cookbook publishing, even as Richard seemed to have little interest in putting her biography on the page. The foreword is spare, a mere paragraph long; headnotes—even for that dream melon of hers, which was recorded in her cookbook simply as “watermelon ice cream”—are nonexistent. Richard appears in the book photographed from the shoulders up in a three-quarter profile, smiling gently. Her dedication—to the late “Mrs. Nugent B. Vairin, whose kindness, advice and assistance has made this book possible”—is one of the few indications of the journey that brought her to this cookbook.

What spilled forth in the 139-page book was a compendium of over 300 recipes. At its core, Lena Richard’s Cook Book is primarily a teaching book—one without presuppositions about its reader’s skill level. “This book is an attempt to put the basic facts concerning the art of cooking into a form that may be easily understood by the youngest housewife as well as the most experienced chef,” Richard wrote in her two-paragraph preface. She taught her readers how to take five pounds of crawfish and turn them into a bisque cooked over a slow fire; how to make a proper roux for a vat of gumbo; how to poach red snapper in a spiced broth for court-bouillon. These foods had once been the province of the city’s moneyed class. Like Richard’s cooking school, this cookbook democratized access to culinary pleasure that had long been gatekept. The best way to fight such discrimination, Richard understood, was through the transmission of knowledge.

Within a week of the book’s publication, she had found herself inundated with letters from New York, as well as Philadelphia and Boston, inquiring about ordering it. So in July 1939, Richard stuffed her bags with ten pounds’ worth of dried shrimp, pure cane syrup, shelled pecans, and brown sugar—tucking a copy of that blue book of hers underneath her arm—and headed up to New York. Having debts to pay off, Richard needed to work indefatigably to make sure her cookbook reached readers well outside New Orleans. Maybe, she thought, she might even find the book a proper publisher.

During that trip, Richard scored a meeting with Clementine Paddleford, whose renowned column at the New York Herald Tribune made her America’s preeminent food journalist. Richard prepared the journalist a showstopper called a scale fish. She boiled and flaked a firm-meated fish, preserved its stock in gelatin, and then filled a fish-shaped mold with the flake-and-gelatin mixture, along with a pattern of black and green olives. The fish’s tail, fins, gill, mouth, and eyes were all composed of slices of pimiento. Like her dream melon, this was a whimsical dish meant to subvert a diner’s expectations.

“Cook From New Orleans Shows Northerners ‘Tricks of Trade,’” read the resulting headline from Paddleford that ran in the Tribune on July 8, 1939. With the help of Paddleford’s powerful pen, Richard, who had been recording sales of her book diligently in a notebook, sold 700 books during her month-long stay in New York. Her debts disappeared.

By the time Richard came back home from that New York sojourn, her book had attracted the interest of an up-and-coming editor named LeBaron “Lee” Barker, who worked for the publisher Houghton Mifflin. Barker had visited New Orleans in December of 1938 and was utterly taken with Richard’s cooking. With Barker’s advocacy, Houghton Mifflin offered to republish her book with an introduction by the white Southern writer Gwen Bristow, who praised Richard as “a great cook, by which we mean that she is a great creator of joy.” Though there is little indication of how Richard felt about the endorsement from Bristow, or even the extent of their relationship, attaching the respected, nationally recognized name of a writer like Bristow would have validated Richard’s book in the eyes of white America. That was precisely the response upon the book’s national publication in the summer of 1940, an occasion noted by the likes of the New York Times, the New York Herald Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times. As the book gained national traction, some journalists were delighted by the precision of her measurements—no vague “smidges” that were de rigueur in other cookbooks of the era.

Not everyone was impressed. The book was “uneven and disappointing,” in the estimation of Town & Country, “for, as is often the case, the author has scaled down some of the recipes’ richness to the limited budget, which is more than usually angryfying [sic] when it comes to Creole food.” Such a response might reveal the expectations Richard now found herself saddled with: Newly in the national spotlight, she had to answer to many parties, some of whom had assumptions about her people’s food.

The leap to wider recognition came with other trade-offs, too. Houghton Mifflin’s reissue of the book effectively eliminated what McCulla told me was Richard’s “personal touch or identity from a reader’s very first encounters with the book.” To start, the title was swapped from Lena Richard’s Cook Book to the more generic New Orleans Cook Book. The book’s interiors anonymized her further, doing away with that distinctive portrait of Richard that had greeted the reader in its initial printing. The result was a book that felt more clinical than intimate.

Still, the national publication of the book opened doors. The team behind the Bird & Bottle Inn, a restaurant in Garrison, New York—a hamlet that was often a destination for Manhattanites who wanted a reprieve from the city—recruited Richard for a one-month cooking trial. She would dazzle them to such a degree, handily preparing food for a crowd of fifty, that at the end of the trial they promptly crowned her chef. “To Queen, who in 3 short weeks has done more for us than we can every [sic] repay,” Constance Stearn, one of the proprietors, later wrote of Richard.

At Bird & Bottle, Richard became especially well regarded for her shrimp soup Louisiane, a shrimp-and-vegetable bisque tickled with bay-Tabasco peppers (which she always had in her apron pocket). This genre of restaurant was far different from what she’d grown accustomed to in New Orleans. Patrons included Hollywood stars and high-class business leaders, and Richard could now showcase her Creole cooking, displayed on a chalkboard menu, to elite diners outside her hometown.

“She had this opportunity where she cooked her way into the position as head chef at, you know, a more sophisticated restaurant,” Young explained. It was a time when Black entrepreneurs, especially women like Richard, had difficulties securing capital for their own ventures. But her reputation and force of personality were transforming Richard’s name into a buzzword; when she returned to New Orleans the next year to open her own restaurant, Lena’s Eatery, she advertised it as “The Most Talked of Place in the South.”

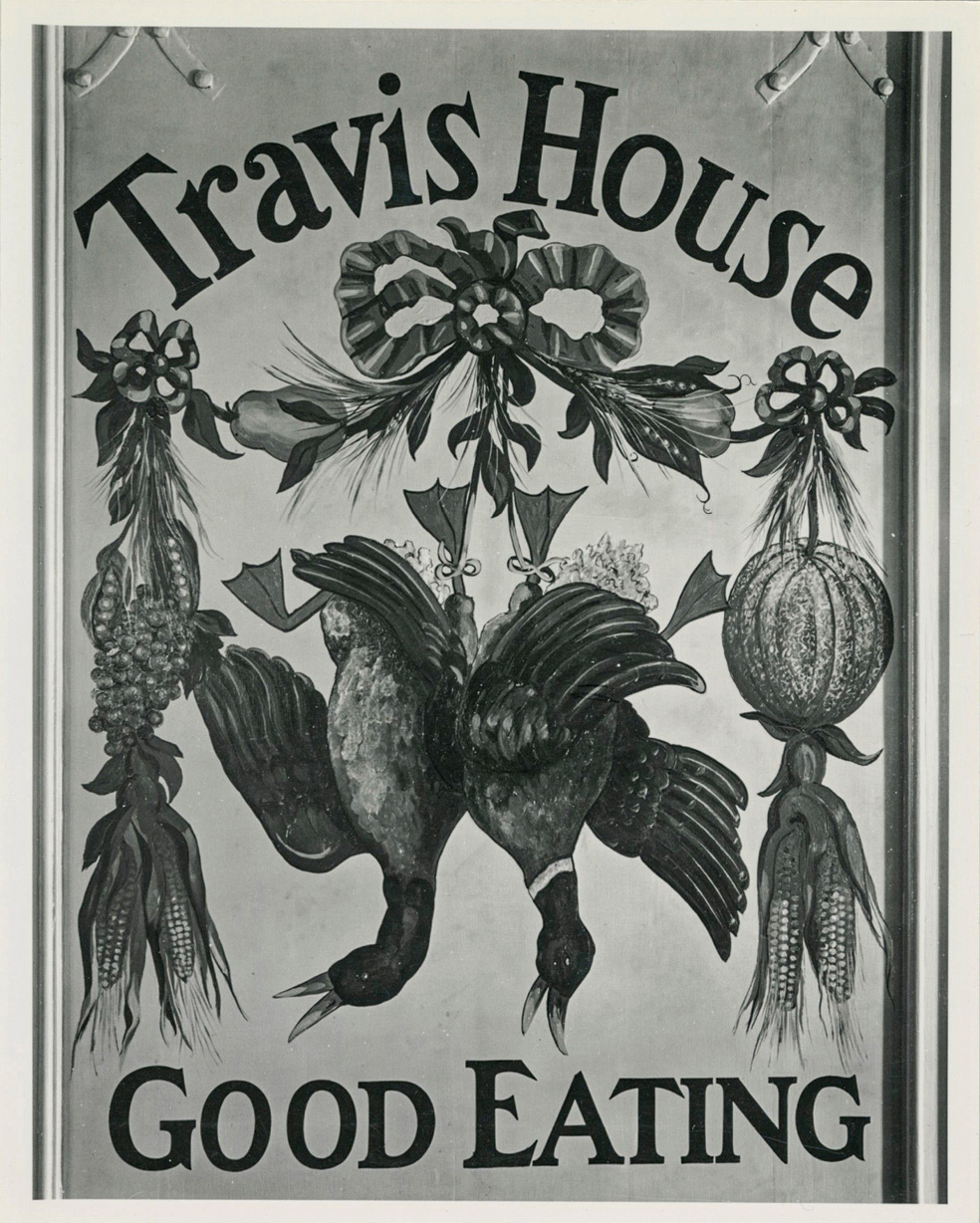

After just a year at Lena’s Eatery—whose eventual fate was uncertain, Young said, though it likely closed down during World War II—she was pulled up to Williamsburg, Virginia, to serve as the head chef of the Travis House, whose proprietor hired her on the strength of her work in Garrison. The offer would have been an attractive one to Richard, Young said, giving her the chance to spread the good word of New Orleans cooking to diners well outside the city, thus augmenting “how many people across the country knew who she was.” Young allowed that Richard leaving her hometown so often may have had consequences for her relationships in New Orleans. Still, her customers at Williamsburg—many of whom were military members and their families from a nearby base, as World War II still raged on—would line up out the door in order to eat her food. (“They ate like locusts,” Richard would later observe of the “boys” from Camp Perry.) The restaurant even invested in a standing freezer to store large quantities of gumbo that they could then distribute to people who wanted to eat Richard’s food at home.

But Richard was as much the star as her food. Richard “wasn’t a chef who was hidden behind the kitchen door,” Young said. In fact, she was such a draw that Winston Churchill’s wife, Clementine, and the couple’s daughter, Mary, even asked for Richard’s autograph after a meal there; “I’d like to borrow Lena,” another diner wrote in the guestbook.

“I hate throwing around the term ‘celebrity chef,’ because it’s so controversial,” Young said, “but she was a known entity.” Patrons would speak lovingly of her smile and her charm, as well as the majesty of her food.

By the spring of 1945, though, New Orleans called again, and she would spend her career from that point forward more firmly resituating herself in the city she had long called home. She forged a partnership with Bordelon Fine Foods, a company headquartered in Metairie, in the New Orleans area, to sell frozen renditions of her food. In pints, quarts, and five- and ten-gallon containers, she would prepare shrimp Creole, turtle soup, gumbo filé, then freeze and distribute them across New Orleans, building on her work at the Travis House. She scaled the business to the point where she could hire women to help her out at the factory; by 1946, she was shipping her frozen foods to various points in the South through Mid-Continent Airlines—and eventually, all the way to the West Coast, and then down to Panama with the help of Pan-Am. (What became of the business from the 1950s onward is unknown, Young said.) Her scope of influence became international over the course of that decade.

Frozen food technologies were gaining greater sophistication in this period, though this was before frozen dinners became widely adopted in the American diet, making Richard a pathbreaker. In a few years, those convenience foods would gain another colloquial name: the TV dinner.

On December 18, 1948, Louisiana’s WDSU-TV aired its inaugural broadcast, becoming its home state’s first television station. By the next fall, the fledgling station decided it wanted a cooking program. It was a time when the likes of the patrician Briton Dione Lucas and the jolly James Beard were hosting cooking shows broadcast across America, but the genre was still searching for a concrete aesthetic identity. The network initially wanted a straightforward show of baking and cooking demonstrations, along with helpful kitchen tips for housewives. The suits at WDSU had one person in mind for this role: Lena Richard.

That year, 1949, had been a busy one for Richard, keeping her in the public eye. She continued her work as a teacher, specifically for Black women: That year, a throng of three thousand Black women filed into the auditorium of the Booker T. Washington High School to attend a demonstration put on by Lena Richard’s Cooking and Baking School. She also began operating the Gumbo House, another restaurant, that same year. But live television was a new frontier for her—and for Black women, more broadly.

“The times being what they were, it was extremely rare to see someone like Lena Richard on television anywhere in America, but especially a southern city like New Orleans,” said Dominic Massa, author of New Orleans Television (2008). Back in 1948 when WDSU first began operations, only an estimated 100 television sets even existed in New Orleans. “That number certainly grew quickly, but obviously the audience was not nearly what it would become over the next decade,” Massa said. “So Lena would probably have become an even bigger phenomenon had she come along just a few years later.” By February 1949, there were an estimated 3,000 sets owned by people in the city; a year later, there were roughly 18,000.

Richard’s show tended to follow a one-dish-a-day structure, with each thirty-minute segment devoted to the creation of a specific recipe. In fact, the show began with the name A Dish a Day before shifting to a new title that put its host front and center: Lena Richard’s New Orleans Cook Book. Much of the program’s audience, Young said, consisted of wealthier white newlyweds who looked to her to learn how to cook, say, grillades—frying breaded veal medallions gently in deep fat until they turned brown. Young’s recollections of conversations with some of these women over a decade ago during the course of researching her book—nearly sixty years after Richard’s death—give us a sense of how memorable Richard’s screen persona was.

“She had the kind of presence and ability to communicate where it really felt like she was in the room with you, speaking at you directly,” Young said. Television screens tended to be tiny back then, broadcasting blurry black-and-white images, but Richard transcended the medium’s shortcomings.

As to the specifics of her onscreen persona, however, there’s little we can know. Richard was working in television long before proper preservation of such media was standard, and no tape of her show survives. “One of the biggest regrets for folks like me who study and appreciate early broadcasting history is that—TV technology being what it was back then, and with all shows airing live—there are no recordings of those early shows,” Massa, the television historian, said. “That is unfortunately the case for so many of our TV pioneers, whose work lives on in memory only.”

A handful of photographs are the only visual remnants of Richard’s groundbreaking foray into television. The most famous depicts Richard alongside her daughter on a temporary set painted like an open-hearth colonial kitchen. Another photo taken from a higher angle, showing the same setup from that day, also exists. Despite the antebellum backdrop, Richard looks every bit the professional, wearing a button-down shirt and glasses. As in her other pursuits, Richard seemed unwilling to genuflect to the limiting stereotypes white residents of New Orleans may have had of Black women like her.

A less widely circulated photo shows her at the new WDSU studios in a more modern kitchen, outfitted with sleek General Electric appliances. Taken in 1950, the photo shows Richard surrounded by her colleagues at WDSU as they attend the one-year anniversary party for her television show—one that had made history. Most everyone in the frame is smiling. Richard herself is pictured standing near the left side of the frame, her face turned away from the lens. Her presence—even in this document of a day predicated on celebrating her, a remarkable achievement in a career that would soon be cut short—is, both visually and symbolically, obscured.

Photograph by Carter/Reddy

Just weeks later, in the early hours of November 27, 1950, Lena Richard began to cough.

It was just past midnight, and she had returned home from a long shift at the Gumbo House. She had spent the previous night entertaining a patron who’d flown in from Los Angeles and made her first stop at Richard’s restaurant. The visitor asked to sample the whole menu, a request that Richard happily obliged, cooking each item herself. Bone-tired and suffering from high blood pressure, she called her daughter and husband around 2 A.M. “I am going home now,” she cryptically said to them, “and there are things I want to tell you.”

What she wanted to tell them is not known: Richard would not make it through the night. She succumbed to a heart attack, and was laid to rest the Friday following her death. She was fifty-eight.

The news made scarcely a whimper in the local press, despite the enormity of her contribution to the city’s culture. “I can’t speak for the editors’ motivations,” McCulla, the New Orleans food expert, told me. “There was no apparent reason that I know of beyond her race for their abbreviated coverage of her death. Certainly there was a long history in New Orleans of Black women and men cooking behind closed kitchen doors and not being celebrated as culinary personalities. Newspapers’ coverage of Richard’s passing conformed with this exclusion.” Her death gained more substantial coverage in African American newspapers outside the city, like the Chicago Defender and the Cleveland Call & Post. A day after her death, WDSU aired a tribute to her. And that was the last New Orleans saw of Lena Richard’s television show.

Ayear and a half after Richard’s death, WDSU decided to revive its cooking show under the title of New Orleans Cook Book, as the nationally printed version of Richard’s cookbook was called. But crucial details were different. A Black woman named Ruth Prevost led the show, and, unlike Richard, the network wanted her to embody a regressive image of a personality the network dubbed “Mandy Lee.” Like the “Mandy” in Natalie V. Scott’s Mirations and Miracles of Mandy, this persona was a culinarily omniscient Black female cook who nevertheless occupied a position subordinate to the white women who soaked in her knowledge. “She was really compelled to dress in the way of a stereotypical, Southern mammy,” McCulla said of Prevost. “She wore a red-and-white checked dress and had a bandana.” Worse, some journalists in the New Orleans press would patronizingly refer to Richard as the first of WDSU’s Mandy Lee personalities, despite Richard’s every effort to resist such racist pigeonholing throughout her lifetime. (Prevost, for her part, would die of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1954 when she was only in her mid-thirties, and her show ended.)

In the years immediately after Richard’s passing, her family would do its best to extend her work’s longevity. The Gumbo House remained in operation until 1958. Her daughter Marie would continue to work in food as more New Orleans cooking personalities—and, in particular, Black women, like Leah Chase of the restaurant Dooky Chase’s—brought the city’s cooking to the national stage. It’s unclear if Richard’s and Chase’s paths ever crossed, or whether Chase kept Richard’s name circulating in public memory. In any case, the endeavors of Richard’s family to sustain her work certainly created a model other food dynasties in the city would follow: The Chase family continued to pitch in and assist in operating Dooky Chase’s even after the death of its figurehead, Chase, in 2019.

On the national level, as television cooking stars like Julia Child rose to prominence in the 1960s, the archetype of the television chef would calcify into a homogenous—and white—figure. “I picture a white woman in an apron with her hair short—you know, close-to-the-head hair, not loosely about her face—very home ec-looking,” Kathleen Collins, author of Watching What We Eat (2009), a history of food television in America, told me when I asked her what the typical television chef looked like in that period. Exceptions to this rule were few. Local markets saw Black figures like Carson and Beatrice Gulley, a married couple, of What’s Cookin, broadcast in the 1950s in Madison, Wisconsin. It wasn’t until 1975 that LaDeva Davis, a junior high school teacher from Philadelphia, became the first Black woman to host her own nationally syndicated cooking show with What’s Cooking? on PBS.

When Klancy Miller, author of For the Culture: Phenomenal Black Women and Femmes in Food (2023), first learned of Richard’s work in 2017, she was dismayed to learn that no footage of the show survived, but nevertheless was “instantly in awe” of the heights Richard climbed in her varied career. “I just think it’s really cool that she had such a broad area of activity and work that she was the engine of,” Miller told me.

Miller sees Richard’s influence most clearly in the work of the late multi-hyphenate B. Smith, who was the “torchbearer” of Richard’s legacy through her work on television, in restaurants, and in print. “She is a modern food brand person who had an imprint on television as well as other forms of media,” Miller said.

But Richard’s story has also guided Miller in her own work; she provided a “blueprint,” Miller told me. “There are people who came up in harder situations than I have who mapped out seemingly extremely difficult paths and flourished,” Miller said.

There are still those who fight to keep Richard’s flame alight within New Orleans. The chef Dwynesha “Dee” Lavigne first came across Richard’s name a few years ago, when she was in her late thirties and touring the Southern Food and Beverage Museum. After learning about Richard on that day, Lavigne began researching her, moved by what she found.

“What struck me deeply was how little I knew about her despite the fact that she was from my hometown,” Lavigne told me. “Nobody had ever mentioned her to me—not in school, not in books, not in conversations about New Orleans food culture. It saddened me to realize how her legacy had been overlooked. However, as I learned more about her extraordinary life and accomplishments, that sadness turned into a sense of purpose.”

She harnessed that energy into opening the Deelightful Roux School of Cooking in 2022, reportedly the first cooking school owned by a Black woman in New Orleans since Lena Richard’s. Lavigne finds that so many of the structural inhibitors that Richard combatted in her lifetime persist today.

“I believe that one of the biggest challenges Black women in the culinary world still face is a lack of recognition,” Lavigne said. “While there has been progress, systemic barriers like funding and support remain significant obstacles. Even for talented chefs, there’s often an expectation that women—especially women of color—are confined to domestic roles, limiting their potential to achieve greater recognition or success.”

Lavigne has sought to fight such marginalization through her own work. A copy of Lena Richard’s Cook Book, she said, sits on the shelf in her kitchen. She shares Richard’s story with every class she teaches. And whenever she tells her students about her own journey, she makes it a point to mention that Lena Richard came before her, so that they, too, will know her name.

Buy the issue this article appears in here.