The Legacy of Rock Hill, SC’s Bleachery

How the Bleachery impacted labor, family, and the local community

By Darren E. Grem

All printed fabric swatches from Rock Hill, South Carolina. Courtesy Baxter Mill Archive;

Rock Hill Printing and Finishing Company worker at a machine printing American flags, 1959. Photograph from Accession 567

William H. Grier, Sr. Scrapbooks. Courtesy the Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections at Winthrop University

Paw-Paw worked at the Bleachery in Rock Hill, South Carolina, for thirty-five years. I barely remember the man my mother recalls: lanky but strong, with a jutted jaw, jet-black hair, winsome smile, and sky-blue eyes conveying the piercing kindness that all good fathers and grandfathers have. Even when his strength faltered and his hands failed, his eyes kept their color. Until they didn’t. Parkinson’s disease is a horror.

By the time I needed babysitting, he and Maw-Maw were retired, living in a suburb dotted with former textile workers like them, not far from the Bleachery. They had met during a baseball game near where he grew up along the Catawba River among cotton patches, softwood forests, and wild spider lilies, with a railroad line within earshot. He was twenty-two; she was eighteen. They married in 1934, a year of hard times. A son came in 1936, another year of hard times. Relocating to Rock Hill, he made ends meet through pick-up jobs and Works Progress Administration (WPA) work for FDR’s New Deal until Uncle Sam came calling. In 1943, he became the first father in York County drafted for the U.S. Army. He shipped out for the Alaskan hinterlands and Aleutian Islands after basic training. For almost two years, he did more ice fishing, sightseeing, and engine repair than soldiering.

Paw-Paw mustered in a private and mustered out a sergeant. He returned to Rock Hill but wanted to re-enlist. Maw-Maw said no. They had another child, my mother, in 1946. He got a job at the Bleachery, joined a labor union, and eased into work as a shop-floor mechanic. He never saw Alaska again.

Originally, the Bleachery had been an automobile plant. Back before the “Big Three” centralized the U.S. auto industry in Detroit, dozens of homegrown manufacturers put out makes and models. Anderson Motor Company, chartered in 1916, did the same, building luxury touring cars. “A Little Higher In Price, But Made In Dixie,” went their slogan. Anderson employed hundreds in Rock Hill before folding in 1925. The plant sat unused until 1927, when Charlie Cobb, a local bank president and head of the Chamber of Commerce’s industrial recruitment committee, started collaborating with the mayor’s office and city manager to repurpose the site.

Cobb drafted a letter and sent it northward in a time when Rock Hill was doing well, growing in population and economic vitality. It was a different story outside city limits. Prices for cotton and tobacco—staple crops in the Carolina Piedmont—nosedived after the military no longer needed cloth and cigarettes for World War I. Farmers reluctantly cut production or diversified their yields to compensate, only to see a few years of market ups and downs take a turn for the worse in 1925–1926 due to overproduction. Prices fell again. Debt ballooned. Farms foreclosed. Drought and the boll weevil kept viable crops from market, as did labor shortfalls. Tens of thousands, especially black Carolinians, kept leaving the South. Then, the national economy collapsed and “hard times” became the watchword of the 1930s. New Deal policies helped with agricultural relief and independence from sharecropping but also enabled land grabs, pesticides, tractors, and, especially after World War II, mechanical pickers. Mules and manpower simply were not needed as much as the rural South turned toward agribusiness. Paw-Paw probably learned his first lessons about fixing machines while still on a farm near Catawba. But the world of his upbringing would never be the same again.

By the time he and Maw-Maw resettled in Rock Hill in 1936, the repurposed Anderson plant had been offering a new way of life for people like him for almost a decade. Archie O. Joslin, a young executive at the New York–based textile firm M. Lowenstein and Sons, had received Cobb’s letter and, after touring the Piedmont, expressed interest in the Anderson site. In 1928, Lowenstein and the city worked out terms satisfactory to both. An expanded, 300,000-square-foot industrial complex opened the next year. Incorporated as the Rock Hill Printing and Finishing Company, the complex became known locally as “the Bleachery.”

A modern marvel requiring five miles of underground water pipes, a pumping station, a power house, and $2 million to construct, the Bleachery started receiving “greige goods” (unfinished cloth, colloquialized as “grey goods”) from nearby textile mills for bleaching, dyeing, printing, and finishing in October 1929. Coincidentally, it opened the same month as Wall Street’s great crash. Lowenstein barreled ahead, hiring and training bleachers, rollers, engravers, mechanics, and managers. In doing so, the company fit into a generational crusade. Since Reconstruction, local boosters and outside investors had promised a “New South,” enabled by industry and urbanization, with Atlanta and Nashville serving as model cities. In Birmingham, the “New South” meant mines and blast furnaces. In the mountains, timber and mining. In Texas and Oklahoma, oil derricks and refineries. In the Piedmont, mills and light industry, generally fed by forests, tobacco, and King Cotton. Seven textile mills signaled the New South’s arrival in Rock Hill before the Bleachery’s founding, as did the Anderson plant. Railroads tied all these New Souths together while intertwining the region with a broader nation and world.

Field. Factory. Financier. Main Street. Wall Street. And profit, made possible by the lives and labors—and, at times, lost lives or maimed limbs—of people like Paw-Paw and Maw-Maw, working within rules and roles both written and unwritten.

Race ordered the New South, and, at the Bleachery, its all-white management made it clear from the start how work and wages—higher than at other cotton mills—would divvy up. White over here, wages up here. Black over there, wages down there. Everyone inside the Bleachery was white. Men tended to run Lowenstein’s machines, whirring every weekday in ten-to-twelve-hour shifts, although shop-floor tasks such as engraving involved women. Blacks could work as janitors but mostly stayed outside the main buildings, loading and unloading shipments. Color conveyed finality, akin to the Bleachery’s tagline. finish by rock hill, it read, dyed in color or in stark black and white.

If typical in terms of its business plan and racial rules, as a unionized plant, the Bleachery stood out. On nearby Wilson Street, locals set up a union hall in 1929. Serving white workers citywide and the Bleachery’s specialized machinist, engraver, and printer unions, the hall would center Paw-Paw’s life and community. By the mid-1930s, the generalist United Textile Workers of America (UTW) met there, counting Rock Hill as its Southern home.

Strikes revealed the importance of organized labor at the Bleachery. The first, in 1933, was brief and over misunderstandings surrounding wage rates, shorter hours, and forthcoming federal labor guidelines. The next action joined the largest coordinated work stoppage to that point in U.S. history: the General Textile Strike of 1934. Some 400,000 workers, organized to affirm the New Deal’s favorable textile code, shut down plants and sparked reprisals from Alabama to Maine. Rock Hill’s newspaper described the Bleachery’s operations as “crippled,” while the UTW strike chairman cast the “general situation excellent” with a “good showing” in the streets. Though hopeful for a “big day” for the strike, men started to cross the picket line in front of hostile crowds, as the South Carolina National Guard policed testy exchanges.

Shockingly, the Bleachery stayed open in 1934, unlike other cotton mills in Rock Hill or across the Piedmont. Two years later, however, managerial flakiness regarding contracts and hours caused another strike, this time led by printers. They used their leverage as essential workers to logjam the entire finishing process. “[T]he sentiment of the rest of the plant as well as that of the citizenry of Rock Hill was bitterly against [the printers],” claimed reports, which cast strikers as “influenced by an outside element which apparently has no regard for southern labor.” The printers and their union pushed back as engravers—another specialized workforce—joined them on the picket line. Labor leaders put their efforts in moral terms, criticizing the company’s “denial of the right of labor to organize for its common good as it is clearly given the right to do by an act of Congress,” likely meaning the recent Wagner Act. In response, management laid off regular workers to stir division along the line, then later rehired them to work with replacement printers. Someone fired a shotgun at a printer’s home. Picketing kept up. Intimidation, arrests, and indictments turned into an uncertain truce until the National Labor Relations Board charged Bleachery management in 1940 with various illegal actions and ordered the reinstatement and backpay of six fired printers. The Great Depression broke many things, just as a devastating world war remade them.

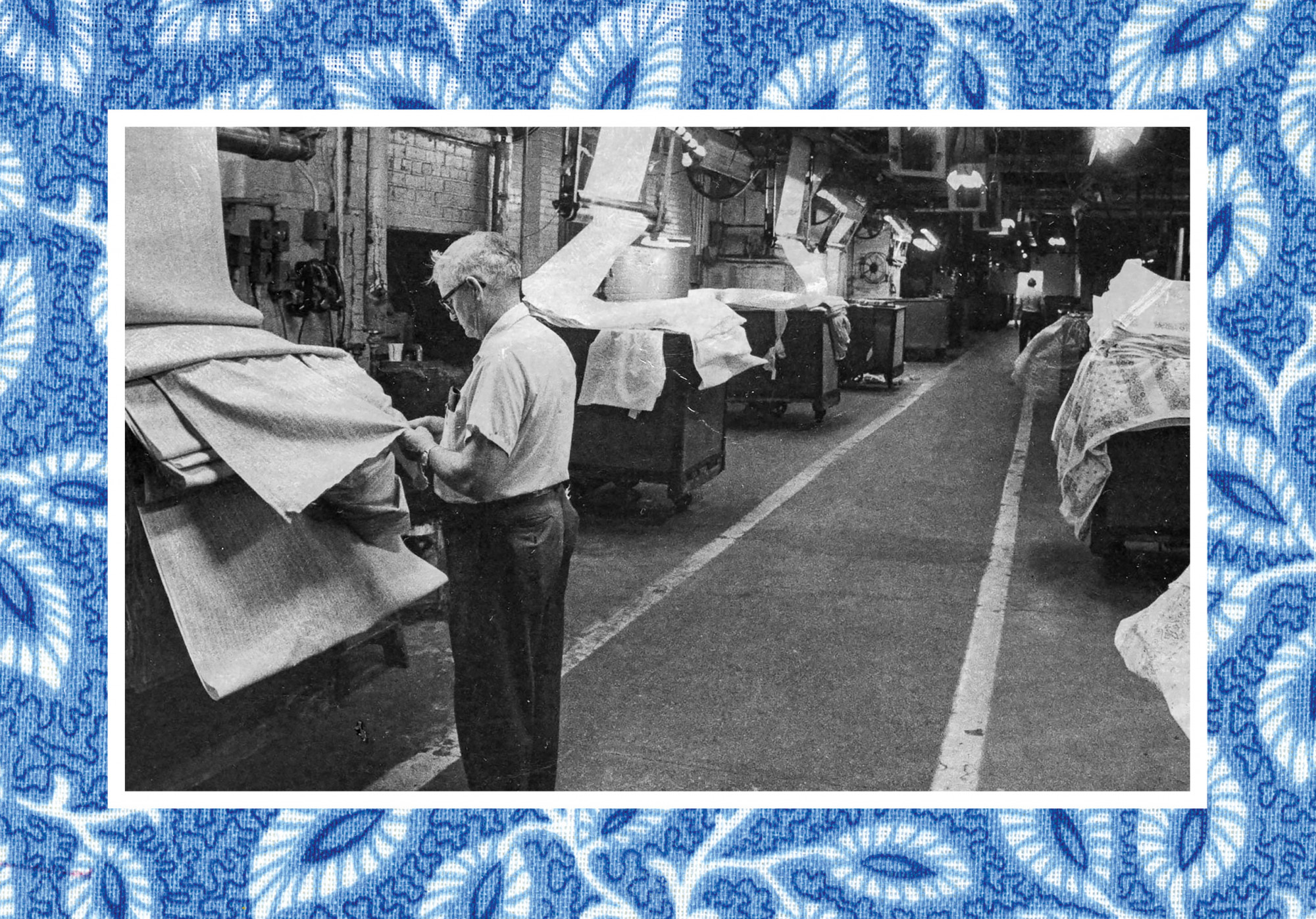

James H. Hines inspects cloth, Rock Hill Printing and Finishing, circa 1970s. Photograph courtesy the Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections at Winthrop University. From Acc. 1771 Rock Hill Economic Development Collection

While Paw-Paw served his country in Alaska, Maw-Maw served hers on the home front, splitting time between the tasks of motherhood and the nearby Aragon Mill. A spinning frame there clipped the tendons in her pointer finger, which she held bent for the rest of her life. The Aragon and other mills around Rock Hill churned in unison with the Bleachery, producing countless uniforms, parachutes, sandbags, and bandages. The military enlisted over half of the 2,100 men and women employed at the Bleachery in 1941. Floated by defense contracts, wartime work equated to patriotic sacrifice for the Stars and Stripes, which the Bleachery also printed and finished for Americans to buy and fly. to the honor of our boys in the service of our country, read the plant’s entrance. Some sacrificed all; 114 did not return to York County.

But Paw-Paw did. He went back to his prewar job at a local body plant for trucks and buses. The lure of a few more cents per hour pulled him over to the Bleachery, as did a slightly shorter walk to and from his house on Lee Street and newborn baby girl. Paw-Paw joined a union, likely because it mirrored the camaraderie of the army, certainly because of the union’s promise of better pay and a pension. Monthly dues also bought him a seat at the union hall, right as another union came southward: the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA).

In 1939, the American Federation of Labor (AFL)-affiliated UTW had joined with a Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO)-affiliated counterpart to create the TWUA. Charging into the South under the banner of “Operation Dixie,” the CIO wanted the region’s workers organized, a tall task. Companies often stoked fears of racial integration or wage equalization, which undercut cross-racial solidarity. Such efforts had kept the New South a lower-wage, under-unionized region for decades and were a threat to the CIO’s postwar standing and the labor movement generally. Without Operation Dixie, companies up north might keep sending production and jobs southward or even abroad, endlessly seeking cheaper labor and laxer regulations—or what boosters and elected officials regionwide often trumpeted as the South’s “good business climate.” Paw-Paw was likely one of the new recruits in a town that, in the estimation of one labor activist in 1950, stood as “one of the most organized cities in the South.”

By 1956, organized labor clearly had disproportionate influence in Rock Hill. Various unions had organized most of the Bleachery’s workforce of 4,200, which itself constituted about twenty percent of the town’s residents. A mid-century boom in consumer goods, textiles included, tended to align white-collar and blue-collar interests at the Bleachery, at least tacitly. Enlarged by the mid-1950s to over 1.5 million square feet of industrial space, and covering about thirty acres overall, the Bleachery seemed futuristic with its state-of-the-art finishing machines and industrial products. Rayon, for instance, was finished in 1938 for the first time in the South at the Bleachery and stayed a signature product. Steady growth made for steady work. Two to three shifts ran every weekday, eight hours each.

Paw-Paw certainly had enough work to keep him busy, applying the mechanic’s know-how he’d picked up from Catawba and Alaska tokeep the Bleachery’s machines up and running. Maw-Maw stayed busy too, having left the Aragon to work part-time at their Methodist church. Life seemed predictable, consistent, even ascendant. Lowenstein’s trademark label, first deployed in the mid-1930s but more apt twenty years later, conveyed workers’ expectations. “Build and Build and Build” to the “Peak of Perfection” it proclaimed. Its logo—the Rock of Gibraltar, craggy but climbable—seemed symbolic of the Bleachery’s future.

But disaster lay in wait, as did old grievances. A fire a few weeks before Christmas in 1954 almost led to the Bleachery’s closure. “I would not have given 15¢ for the main part of our plant,” the company’s general manager Bill Grier said later about the damage. Rebuilding took months, but recovery came quickly. A new add-on, the Grier Division, opened in the manager’s honor in 1955. Forty-five rolling machines put out 2.2 million yards of product each day. According to the New York Times, Lowenstein annually printed “enough fabric to span the distance between the earth and the moon with a good jag of goods left over, or enough to wrap around the equator more than eleven times.” Profits were satisfactory, even stellar. Wages less so.

Strikes again popped off in 1948 and 1951, spearheaded by the TWUA in tandem with Operation Dixie, which collapsed regionwide in 1953 but left its mark in Rock Hill. The TWUA called for another strike in 1956 with AFL-CIO support, which demanded a national boycott by its affiliate unions of Lowenstein products. Unionized or sympathetic workers—some 3,200 strong initially, about seventy-five percent of the Bleachery’s total workforce—hit the picket line. Facing a labor shortage, management hired scab workers to keep the plant running. Shop-floor tensions turned into harassment and violence in the streets between strikers and scabs. Paw-Paw sent his baby girl to Michigan to keep her from getting mixed up in it.

The Bleachery’s bosses felt the heat, but so did labor leaders as weeks turned into months of inaction. By then, according to company estimates, nearly a third of the union had trickled back to work. With the plant at near full production, management saw little reason to negotiate. After fifteen weeks, the strike ended. Wages soon increased above the TWUA’s demanded level, likely a managerial ploy to undercut the union’s appeal. Paw-Paw told uncertain stories about the 1956 strike, but only years later. His eyes spoke of memories pockmarked with silences.

The Great Depression broke many things, just as devastating world war remade them.

Other deferred dreams threaded into the Bleachery and the avenues paralleling Rock Hill’s Main Street, aptly named White Street and Black Street. Black men and women helped put out the fire that nearly destroyed the Bleachery, but they could not regularly work with whites in the main complex. Blacks did not receive equal pay for equal work. Black women labored in the kitchens and backyards of white workers like Paw-Paw and Maw-Maw, yet their children attended segregated schools. The Bleachery’s annual Christmas gift giveaway unfolded along segregated lines. Whites here, lined up on the main lawn. Blacks there, lined up on adjacent Stewart Avenue. Joslin Park, a sixteen-acre recreation area for employees and their families, also accorded with racial codes: no blacks allowed. Blacks rarely appeared in photographs with the whites who employed them, even after years spent in intimate quarters. Blacks did not worship in church with whites or vice versa. White souls did not rest beside black souls in cemeteries.

White here, black there—until another New South came rushing in. Sit-ins rocked Rock Hill in 1960. A local Citizens’ Council vowed massive resistance. Most whites and blacks in town kept to themselves or sidestepped committed stances. Demonstrators picketed downtown businesses and tried more sit-ins. A business owner put a gun to a demonstrator’s head and threatened to pull the trigger. A cross burned in front of a black church. In 1961, nine activists took up a “jail-no-bail” tactic, voluntarily serving time at a prison work camp to keep their money out of municipal coffers. They were followed by kneel-ins at white churches, more demonstrations downtown, and demands for admission to Winthrop College, a segregated women’s college. Freedom Riders rolled in, including a young John Lewis, whom local toughs beat up in a Greyhound bus terminal. My mother remembers Paw-Paw’s advice to avoid downtown at the time. In 1964, she graduated in Rock Hill High School’s last all-white class.

Rapid-fire change came to the textile belt and the Bleachery soon thereafter. Another strike in 1967, organized by machinists and TWUA members alike, garnered better insurance benefits and contract assurances. A modern data center went up, signaling a post-industrial, hi-tech South on the horizon. But something seemed awry. Screenprinting led to the end of roller print machines and the need for workers to run them. Polyester replaced natural fibers, stressing the textile market at large. By 1970, the Bleachery’s workforce was down to 3,250. Cost-cutting spurred the decline in part, but automation also factored in. Efficiency measures brought the Grier Division’s closure in 1974. Machinists went on strike again in the same year, demanding higher wages from a company in transition. Incentives to shift production overseas to cut costs met rising inflation brought on by oil shocks. Stockholders demanded a streamlined business less amenable to negotiating with labor. Lawsuits brought by black employees, long forthcoming, challenged racist labor practices at the Bleachery and three unions. Settlements came in 1975, along with $310,000 in backpay to 300 black workers. This next New South made room for amending historic wrongs, albeit right at the moment the Piedmont’s textile industry was moving on and moving out.

Paw-Paw told no stories about his latter days at the Bleachery. Neither did he talk much about a life spent there, at least not while he rocked back and forth in a patio glider, watching as I climbed crabapple trees or hit make-believe home runs in his backyard. In 1973, he and Maw-Maw left Lee Street for a small, two-bedroom suburban house. Rock Hill kept changing. Banks. Highways. K-Mart. McDonald’s. Hospitals. Shopping malls. Cul-de-sacs. Another New South, now repackaged by boosters and business interests as a “Sunbelt.” Still, when he imagined the future, Paw-Paw did so with his union and Bleachery in mind. He bought plots in the historically white Laurelwood Cemetery for himself and Maw-Maw, right across the street from the Bleachery’s twin smokestacks, one still reading R.H.P.& F. CO in white paint, if starting to fade and flake.

Paw-Paw clocked out for the last time in 1981. By then, the Bleachery’s workforce was down to 2,150, about half of its peak a quarter century before. Every textile mill in town had closed. The unions broke as the Bleachery lost jobs, the workers lost wages, and the unions lost dues. Then the bonds of company and town broke, unraveling a generation of intertwined lives and labors.

Freedom Riders Genevieve Hughes and John Lewis visit Rock Hill in 1961. Courtesy Historic Rock Hill

Lowenstein sold the Bleachery in 1985 to Springs Industries, long a regional powerhouse but also beholden to Wall Street’s demands. Springs could not—or did not want to—save the plant, eying business abroad, including in Japan, the very country Uncle Sam drafted Paw-Paw to defeat. That younger man’s past was told in glossy picture books he kept on a side table, a few about Alaska. For Paw-Paw himself, the slips came first, then stumbles. It took him forever to button a shirt. His mind stayed alert, even as his body lost itself. A special kind of horror for a mechanic. By 1989, only nine hundred workers cashed paychecks from the Bleachery. By then, Paw-Paw was in a nursing home. In 1998, the Bleachery closed for good. Springs eased toward its newer New South, a global one, eventually landing in Brazil. Thankfully, Paw-Paw didn’t live long enough to see it.

Paw-Paw died in 1990. Maw-Maw passed in 2004. He wanted his spirit to forever “hear the shift changes at the Bleachery” from the plots in Laurelwood, the din of his world clocking in and clocking out. But for years, little could be heard from his final resting place. Wildflowers grew near bulldozed rubble. The sights and sounds of the Sunbelt’s very own Rustbelt.

In 2010, circumstances changed. Requisitioned by the city and cleaned up, the Bleachery’s sturdiest buildings and twenty-four acres became the anchor for a Knowledge Park district, which included the University Center, a multi-use facility befitting Rock Hill’s new “meds and eds” economy. Piedmont Medical Center, opened in 1983, had already eased the town’s economic base toward health care and medical services. Winthrop joined other Piedmont universities and technical colleges to nurture a professionalized workforce, now garnering know-how from lecture halls instead of shop floors. Today, an onsite Rock Hill Sports & Event Center fits into a town repositioning itself for sports tourism. The Power House, a luxury apartment complex and food-and-entertainment venue, occupies the old power house. Within walking distance on White Street is an upscale beauty shop branded, uncoincidentally, The Bleachery.

Alleane Lawrence at a spinning machine, Springs Mills White Plant, Fort Mill, circa 1970s. Photograph by Andy Burris for the Herald. Courtesy the Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections at Winthrop University. From Acc. 1771 Rock Hill Economic Development Collection

When possible, I stop by Laurelwood to pay my respects to Paw-Paw and Maw-Maw. Across the street at the Bleachery—as around Rock Hill and across the greater South—an unfinished story continues to unfold. It is a story about what newness promises and costs. It is a story about what should or shouldn’t remain. It is a story told in faded smokestack lettering and in forceful lessons about dreams demanded and rights deferred. It is a story replete with memories and silences. A photograph of Alaska. A union card in a drawer. Wildflowers left on a headstone. New Souths all.

This story appears in the Summer 2025 print edition as “New Souths in Rock Hill, SC.” Order the Y’all Street Issue here.