Raw Musics

John Fahey Resurrects the Good Stuff for Nashville's Only Outsider Record Label

By Bill Friskics-Warren

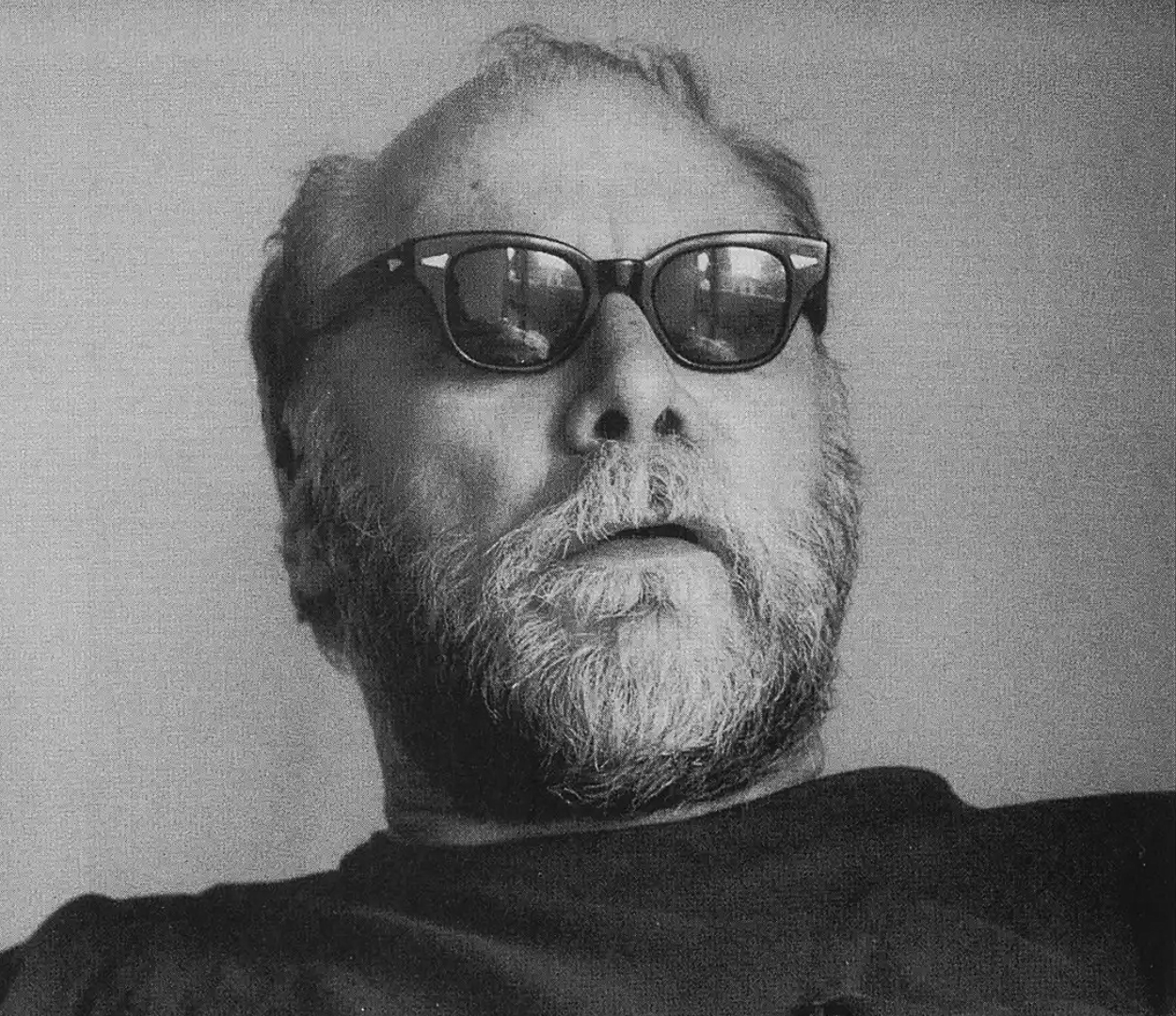

John Fahey Press Photo, Tim Kerr Records. From Issue 12/22 Summer 1998.

In God’s name don’t think of it as Art. Every fury on earth has been absorbed in time, as art, or as religion, or as authority in one form or another. The deadliest blow the enemy of the human soul can strike is to do fury honor... It is scientific fact. It is disease. It is avoidable. Let a start be made...Get a radio or a phonograph capable of the most extreme loudness possible, and sit down to listen to a performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony or of Schubert’s C-Major Symphony. But I don’t mean just sit down and listen. I mean this: Turn it on as loud as you can get it. Then get down on the floor and jam your ear as close into the loudspeaker as you can get it and stay there, breathing as lightly as possible, and not moving, and neither eating nor smoking nor drinking. Concentrate everything you can into your hearing and into your body. You won’t hear it nicely. If it hurts you, be glad of it. As near as you will ever get, you are inside the music; not only inside it, you are it; your body is no longer your shape and substance, it is the shape and substance of the music.

—James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

John Fahey, “the father of American primitive guitar,” knows the fury of which Agee wrote. And yet he didn’t encounter it in the symphonies of Beethoven or Schubert. Fahey’s epiphany came in 1957 when listening to Blind Willie Johnson’s “Praise God I’m Satisfied,” a 1929 blues recording that Fahey and high school buddy Dick Spottswood found while scrounging for 78s in a Baltimore junk shop. Johnson’s guitar playing on the record was hardly spectacular—little different from the syncopated rhythms heard on numerous sides made during the ’20s and ’30s. It was the clash of the bluesman’s bulldog growl and the antiphonal wailing of his wife, Angeline, that made the performance so indelible, less divine than diabolical.

Fahey has sought such revelations—the more visceral the better—for the past forty-one years. He has done so as a guitarist, all but inventing a new school of playing; as a folklorist, “re-discovering” country blues singers Skip James and Bukka White; and as the former owner of Takoma records, operating one of the very first artist-run labels. Not even the health and drinking problems that landed Fahey, now fifty-nine, in a Salem, Oregon, rescue mission during the ’80s could dim his passion for discovery. The iconoclastic albums he’s recorded since returning to the public eye confirm as much. So does Revenant, his new Nashville-based label, an imprint committed to releasing “raw musics” that embody the pioneering spirit of his own work.

The bulk of this legacy, says Fahey, stems from the moment he fell under the spell of the scarifying blues of Blind Willie Johnson. “I was raised on hillbilly and classical music,” explains the guitarist, who today lives in a motel fifteen miles north of Salem. “The culture around us was so anti-black that I didn’t listen to black entertainers. Dick [Spottswood] had played me Blind Blake several times, and Blind Boy Fuller, trying to get me interested. But I had this block against black music. I was only interested in country and bluegrass records. And so he put on Johnson’s record and I got physically nauseated—so much so that I made him take it off and put on a Bill Monroe record. But the thing kept going through my head, and then I made him put it back on and it sounded so beautiful that I started crying. I think that what happened, on an unconscious level, was that I overcame my resistance to the beauties of ‘Negro’ music.”

More than that, the experience redefined Fahey’s whole aesthetic, instilling in him an openness, a hunger for emotional directness, and a contempt for the canons of critics and tastemakers. “Little did we know we had created a monster,” laughs Spottswood, now a noted music historian and record collector. “But John’s life wasn’t the same after hearing Blind Willie Johnson. From that point on, he saw strange connections where the rest of us couldn’t see them. He brought his own sensibility to music that few people cared about.”

After hearing “Praise God I’m Satisfied,” Fahey began incorporating blues phrasing into his classical- and bluegrass-based guitar style—several years before the blues revival of the early ’60s. Fahey was then a philosophy student at American University, where he worked the graveyard shift at a filling station in nearby Langly, Maryland, and honed his playing. It was there, in 1959, that a friend, knocked out by his inventive guitar excursions, loaned Fahey $300 to record his debut album, the title of which, Blind Joe Death, invoked a fictitious black bluesman to whom Fahey attributed the songs on side two of the LP.

Only ninety-five copies of Blind Joe Death were originally available (five others broke en route from the pressing plant). Before long, though, Fahey’s do-it-yourself collection of solo instrumentals had become a cult item. Later dubbed “American primitive guitar,” his maverick compositions and playing style—“like Bartok, but with blues syncopation,” he’s fond of saying—influenced artists as diverse as Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore and Windham Hill founder Will Ackerman.

Fahey put out Blind Joe Death on his Takoma label, named after his birthplace, Takoma Park, Maryland. He continued to release his own records throughout the ’60s, but Takoma was more than just an outlet for his prodigious and increasingly experimental output. The label also began releasing projects by such Fahey acolytes as Leo Kottke and Robbie Basho, both of whom mined the melodic side of their mentors playing, and by dobro wiz Mike Auldridge.

In the meantime, Fahey and his mid-’60s performing partner, Bill Barth, searched the state of Mississippi for blues legends Skip James and Bukka White. After locating them, Fahey went on to record White for Takoma. (He’d hoped to do the same with James, but the two men didn’t get on well together.) In 1970, Fahey published a monograph on Delta blues singer Charley Patton. But he wasn’t content merely to study, or even to “re-discover” and record his heroes. As his friendship with White attests (the two men eventually became fishing and drinking buddies), Fahey wanted to understand these bluesmen and to inhabit the myths that grew up around them.

Doubtless this personal quest, coupled with his bemusement at the sway these gifted yet otherwise ordinary human beings held over fawning white audiences, accounted for Fahey’s ongoing absorption with the persona of Blind Joe Death. “That was a joke,” he says, referring to the high jinks that surrounded the imaginary guitar player, as well as to the mock-serious liner notes that he penned for subsequent LPs. “Back then it was supposed to be impossible to play blues if you were white.”

Joke or no joke, Jim Dickinson, who has recorded with Aretha Franklin, the Rolling Stones, and Ry Cooder, remembers seeing Fahey actually become the chimerical figure at the Memphis Blues Festival in 1965. “He was the first one of what I call the white boys that I saw transform,” Dickinson explains. “I’d seen actors do this, but I never saw a musician go into character before John. He’d walk out onstage and he’d be this twenty-three-year-old white kid. By the time he got to the center of the stage he had transformed into a seventy-five-year-old black man—physically. He’d start to walk slower, then his steps would get smaller and his shoulders would stoop. By the time he sat down with his instrument, he had transformed. He was Blind Joe Death.”

Dickinson likens Fahey’s role-playing—as well as his intuitive grasp of country blues—to a spiritual discipline akin to Zen Buddhism. “He was approaching the instrument in what was then a new way,” Dickinson explains. “A lot of people have done it since, to varying degrees. But I never saw anybody do it before him.”

“Some people look at John as if he was a crank,” notes Jim O’Rourke, one of Fahey’s recent collaborators. “But even when he’s sticking his tongue out at people, there’s a truth and a humanity there—and a humor there as well.”

Fahey’s trickster mentality and his penchant for combining divergent forms and ideas—his fascination with the layering of sound through tape manipulation is but one example—are among the hallmarks of his music. But Fahey’s playful and subversive spirit also extends to his Revenant label, a project that he and his manager-partner, the Nashville attorney Dean Blackwood, launched as a vehicle for releasing “raw musics of all stripes.”

Revenant’s titles have thus far embodied the inscrutable ideal that the two men have set for the label. Nefertiti, The Beautiful One Has Come reissues jazz pianist Cecil Taylor’s riveting 1962 performance at the Café Monmartre in Copenhagen. Music and Dance rescues from oblivion a cassette-only collaboration among British guitarist Derek Bailey, Japanese dancer Min Tanaka, and a Paris downpour. Earliest Recordings: The Complete Rich-R-Tone 78s (1947—1952) compiles the incipient bluegrass of the genre’s all-time most soulful exponents, the Stanley Brothers. American Primitive Vol. I: Raw Pre-War Gospel presents sanctified blues sides recorded by black street singers from 1926 to 1936. And Country Blues, a gripping collection of 1920s Dock Boggs recordings, has lately had reviewers outdoing themselves to join Greil Marcus in hailing the Appalachian singer-banjo player as the pre-modern Bob Dylan.

Revenant also issues newly recorded music, such as Happy Days, a forty-five-minute guitar and hurdy-gurdy meditation by minimalist composer O’Rourke. Salvador Kali, the label’s latest release, is a solo guitar and piano recording by Rick Bishop, co-founder of the pioneering ethno-rock band Sun City Girls.

Revenant’s far-reaching, not to mention obscure, catalog is enough to make the heads of esoterica adepts swim. And yet what unites the imprint’s “raw, unvarnished” releases, explains Blackwood, lounging on the floor of Revenant headquarters—the furniture-less attic of his West Nashville bungalow—is the preservation of each artist’s musical vision in its purest form.

O’Rourke echoes Blackwood’s assessment. “For me,” he says, “the connection is people who try to reach farther than what other people are doing. It’s all folks who, just like John, refuse to settle for the status quo.”

Ever the wag, Fahey describes Revenant’s hermeneutic in less lofty terms than those his young colleagues use. “The real thread connecting Cecil Taylor and Dock Boggs is that one of us likes ’em,” Fahey says, referring to the affective logic that dictates which records he and Blackwood put out. “What’s really interesting about our relationship, what’s really wonderful, is that sometimes I don’t like the stuff that Dean picks. But I let him go ahead and do it, or vice versa. The important thing is that we’re making value judgments and we’re not ashamed to say so.”

The two men met when Blackwood, who had previously worked in the East Coast office of Sub Pop records, wanted to put out several of Fahey’s recordings on his 78-only Perfect label. The guitarist consented, permitting Blackwood to issue his “Evening Not Night (Parts 1 & 2)” and “Morning (Parts 1 & 2)” on thick slabs of black shellac. Soon after that, the younger man started booking Fahey’s live dates. Then, when Fahey came into an unexpected inheritance, he invited Blackwood to start Revenant with him.

Since the two men established the label in late 1996, Revenant has emerged as a standard-bearer for the thoughtful treatment of overlooked artists and their material. Whether accompanied by exquisite packaging or by extensive liner notes, the label’s releases are more like events than mere CDs. In the same way that Blue Note blended sound, written word, and graphics, Revenant’s releases offer a prismatic view of a performers work that invites listeners to respond to more than the music encoded on each disc. With todays commercial labels constantly recycling their catalogs to turn a quick buck, Revenant’s elegant, but never overly reverent, approach to making records qualifies as a lost art. Most labels certainly wouldn’t have issued a set like Boggs’s Country Blues. Bound like a hardcover book, the Revenant CD comes with sixty pages of essays and images—packaging that some observers say has the air of a vanity project.

Fahey concedes that sparing no expense on a project such as the Boggs reissue is an “ego trip,” an extension of a personal aesthetic that perhaps only he and Blackwood share. And yet he also points out that the label has tapped into an audience that is hungry for its outsider projects. Revenant’s Boggs set sold out of its initial pressing of three thousand copies within a month—not bad for an outfit that could qualify for nonprofit status. “What’s interesting,” says Fahey, “is that our records are selling. More importantly, people are saying, ‘Here are two guys who are breaking with orthodoxy and giving us stuff that we didn’t know about. And it’s good!’”

O’Rourke, who runs his own Moikai label, agrees. “It’s a doorway into different worlds for people,” he says. “What makes Revenant different is that someone with actual musical enthusiasm is behind the means of production.”

Jim Dickinson, who is currently working with Fahey and Blackwood on a compilation of recordings by the Memphis rockabilly great Charlie Feathers, waxes philosophical when he talks about what it means to make records. “To me,” he says, “it’s an act of communion between the artist and the producer and someone from whom they are separated by time and space. And that audience, that person sitting alone in his room in the middle of the night with headphones on, he is completing the act of communion.”

Blackwood shares Dickinsons viewpoint, insisting that each Revenant release has a strong spiritual dimension. “All of our stuff has an otherworldly, alien quality to it,” Blackwood says. “And yet, in each case, the artist is ultimately concerned with engaging the human spirit.” It’s an element, he adds, that’s evident throughout Fahey’s work. Whether in his interpretations of popular hymns, his forays into theology, or his efforts to get inside the worlds of forgotten bluesmen, the guitarist has been plumbing life’s mysteries—and forging connections in unlikely places—ever since he first heard Blind Willie Johnson more than four decades ago.

In several respects, it’s fitting that Fahey and Blackwood have dubbed their undertaking Revenant, a French word that means “one who returns after death or a long absence.” The term certainly describes Fahey’s renewed health and career, and even applies to the way he still redeems vintage vinyl from Goodwill stores. It also accounts for his efforts to heighten the visibility of Skip James and Bukka White during the ’60s, and for Revenant’s current role in introducing Boggs and Taylor to unsuspecting audiences. Upcoming reissues of recordings by Hawaiian-style slide guitarist Jenks Tex Carman, Harmonica Frank Floyd, and banjo player Buell Kazee offer further proof of the label’s commitment to unearthing neglected viscera from all genres.

Thus far, though, the most stirring example of Revenant’s conjury remains American Primitive Vol. I, where the ravaged groans of such phantoms as Blind Willie Davis and Blind Roosevelt Graves cry out from oblivion. As with most of the blues singers heard on the record, these men were destitute and disabled during their lifetimes. And yet rather than vanishing, they remain very much alive through the three-minute traces of faith and resiliency included here. Indeed, the very survival of these recordings—in no sense considered art during their day—stands as a judgment against the society that consigned them to its margins. More than that, it testifies to Fahey’s and Blackwood’s willingness to let the rawest cultural expressions speak to them and reconstitute their worlds, as well as, no doubt, the worlds of others.