The End of the Trail

Cormac McCarthy should revisit his home in Tennessee, where stoic cowboys and desert oracles don’t much signify

By Hal Crowther

In a moment of discouragement, a writer I know calculated that every serious book aims itself at the same five hundred serious readers, an elite that doesn’t necessarily include book reviewers. After twenty years on the circuit, he added, a writer has made rhe acquaintance of at least half of these readers. He sees their faces when he sits down to write.

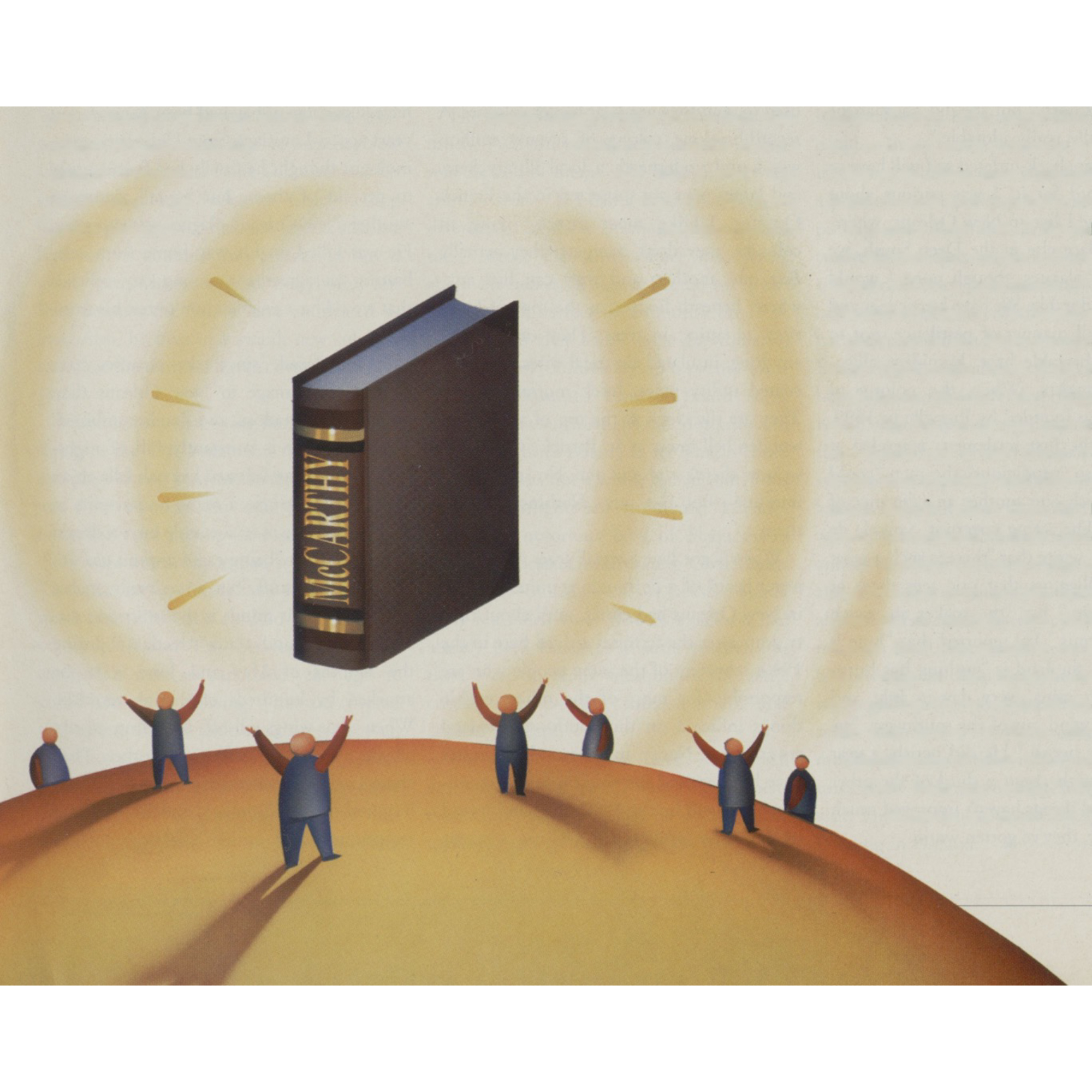

Five hundred is a desperately small number. The word “serious” defies definition, but everyone knows what he means. In an adolescent culture that celebrates illiteracy, literature is once again an intimate enterprise. If publishing is a sprawling flea market of dubious merchandise, the serious business of writing and reading is transacted in one small tent at the edge of the field. Admission is by password only. For years one of the passwords has been Cormac McCarthy.

Thoughtful critics hail McCarthy as the foremost Southern writer of his generation and even as the most gifted novelist writing in the English language. Yet before Knopf engineered the commercial success of his sixth novel (All the Pretty Horses, 1992), in part by compelling him to submit to an interview with the New York Times, most English professors had never read McCarthy, and many had never heard of him. None of his first five novels sold more than five thousand copies in hardback. Without too much effort he could have located all his readers and mailed them questionnaires.

We never heard from him. McCarthy’s reclusiveness and disdain for self-promotion guaranteed his obscurity but enhanced the mystique of a hermit genius. Not even the praise of his peers could smoke him out of hiding. Nominated for a charter membership in the Fellowship of Southern Writers—by no less a champion than Walker Percy—McCarthy respectfully declined. No other writer has ever refused election to the Fellowship. McCarthy’s rootlessness was another eccentricity that fed his legend. Few journalists or photographers pursued him, but the ones who tried found a cold trail of budget accommodations that led from Knoxville to Chicago, New Orleans, Las Vegas, London, Paris, and El Paso. In one of the many books of photographs of Southern writers—most of them posed for effect, like dust jacket portraits—McCarthy is framed in the ticket window of an abandoned train station, wearing an expression that combines annoyance and profound pity for a world where people might covet his likeness.

“A cult following” is the cliche that perfectly describes McCarthy’s readership prior to All the Pretty Horses. But it was always the prose, not the myth, that kept us in church. What is it about McCarthy, the philistines rage, that inspires such devotion? I’d argue that there are only three things, none of them uncommon, that might keep you from admiring McCarthy: a tin ear, a weak stomach, or a hopeful heart. If it’s solace you’re seeking, stay away. (“I know all souls are one soul,” says McCarthy’s Cornelius Suttree, “and all souls lonely.”) But McCarthy at his best—McCarthy writing with the throttle wide open—is still the closest thing to heroin you can buy in a bookstore.

Vereen Bell, who published the first book-length assessment of these novels (The Achievement of Cormac McCarthy, LSU Press, 1988), acknowledges McCarthy’s incomparable style: “His language brings the real world back to us replenished but still familiar, as if we were seeing it truly for the first time.”

My story with Cormac McCarthy is one of a devout reader and a writer he reveres. Idolatry was never a weakness of mine. Only one encounter with a legend had ever left me at a loss for words, and that was in front of the visitors’ dugout at Shea Stadium, when I turned suddenly to find Willie Mays grinning at me and holding out his hand.

I was only twenty-five then. When I was pushing fifty, Cormac McCarthy produced a similar social dysfunction. I hope it doesn’t embarrass Clyde Edgerton, a fair novelist himself, if I describe our behavior when McCarthy, wearing his name tag, materialized improbably at a cocktail party in Cashiers, North Carolina. Clyde and I sort of backed ourselves to within earshot of his conversation, like awed undergraduates at a book signing. I’m not sure we’d have introduced ourselves at all if McCarthy hadn’t turned and offered his hand, like Willie Mays.

“How do you like where you’re living?” somebody asked him, and he answered, “I never liked any place much.” I ended up eating a couple of meals with McCarthy, consciously trying to square this small, neat, courteous man in the blue seersucker jacket with the author of Blood Meridian and Child of God. There was no clue that I was passing the marmalade to a writer whose novels encompass necrophilia, incest, infanticide, and sex with consenting fruit. There’s nothing physically remarkable about McCarthy either, except eyes of the lightest blue in the human spectrum—desert prophet eyes like Peter O’Toole’s in Lawrence of Arabia. Eyes you don’t want to play poker against, because they give away nothing at all.

We talked about our grandfathers. I was surprised to discover that McCarthy is a passionate golfer. The bond between a writer and his reader is a one-way illusion, one that personal contact never strengthens and sometimes destroys. I’m not sure we’re ever intended to see the wizard behind the curtain. Try to imagine a game of golf with Tolstoy or Joyce.

Put me down as an eccentric footnote in the history of American literature, a man who turned down his chance to play golf with Cormac McCarthy. As an anecdote, I decided, it wasn’t worth a threat to my hero-worship or the embarrassment of my long-neglected golf game.

We all liked McCarthy, a pleasant man who showed no signs of the self-involvement and rogue-elephant willfulness common to artists who are praised above their fellows. My positive impression makes it difficult for me to confess my misgivings about his Border Trilogy, which began with All the Pretty Horses and concludes with the current Cities of the Plain. But what does a reader owe a favorite writer to whom he’s offered wholehearted allegiance? Honesty, I think—not the craven rationalizations of the academic who yokes his career to certain writers and their reputations. Who but your loyal readers will tell you the truth?

I think McCarthy, who left his native Appalachians for good with Blood Meridian (1985), has been seduced and in some way misled by the desert Southwest. I hope it’s true that he’s at last found a home out where the antelope roam. No doubt the vanishing American cowboy is a wholesome obsession compared with the pitiful outcasts and damaged, peripheral creatures who populate his earlier novels.

But the West can fool you, I think. I’ve been known to rhapsodize about Western skies and horses grazing against a backdrop of snowcapped ranges, and I own a Stetson the size of a wading pool. The West is expansive and spiritual, but it’s physically empty in a way that entices you to add your own depth and meanings.

McCarthy might have heeded a warning from the late Wallace Stegner: “The West does not need to explore its myths much further; it has already relied on them too long.’’

The Crossing, the second book of the Border Trilogy, begins with a pure masterpiece of a novella about a boy and a wolf. The rest of the novel owes too much to Carlos Castaneda (I pray McCarthy wouldn’t take that as a kick in the stomach). Castaneda’s Don Juan, the Yaqui brujo, was the original model for these desert sages, gypsies, and blind philosophers, scarcely distinguishable from one another, who offer cryptic parables that tease us toward the meaning of life.

“Oracular” is an unbecoming mode for fiction. When Flaubert said that a great writer should stand in his novel “like God in his Creation, everywhere and yet invisible,” he didn’t mean disguised as omniscient pilgrims and mysterious hitchhikers.

Cities of the Plain is a fine tragic novel, better than most of us could write in a lifetime of grim commitment. But it’s Western mythology in all its buckskin trim, with a nod to Larry McMurtry. In place of cursed pariahs, we find upright, compassionate characters who might have borrowed their values from “Gene Autry’s Ten Cowboy Commandments.” Evil trumps virtue, as it always does in McCarthy’s novels. But a Mexican pimp with a wicked switchblade is a pale successor to Blood Meridian’s terrifying Judge Holden, who outdeviled Satan himself. And McCarthy the oracle is at it again in Cities of the Plain, most unhappily in an epilogue choked with perishable profundity.

A century from now, if the habit of literature survives the current cultural holocaust, Suttree will be a benchmark of literacy like Huckleberry Finn or The Sound and the Fury. It pains me to see Suttree’s author chided by some lightweight New York reviewer for “portentous rhetoric” and “pop existentialism.” But McCarthy has been asking for it. He should pay a visit home to Tennessee, where stoic cowboys and desert oracles don’t much signify, where even the best readers resent untranslated Spanish dialogue.

His material success is richly deserved and long overdue. Even outcasts have the right to grow old in comfort. But McCarthy’s old readers liked him standing naked out there on a ridge in the thunder and lightning, expounding (in the words of Vereen Bell) on “the true horror of death, the impersonal relentlessness of time, the cruel absence of God from the world.” We wish he’d throw us raw meat, like he used to.