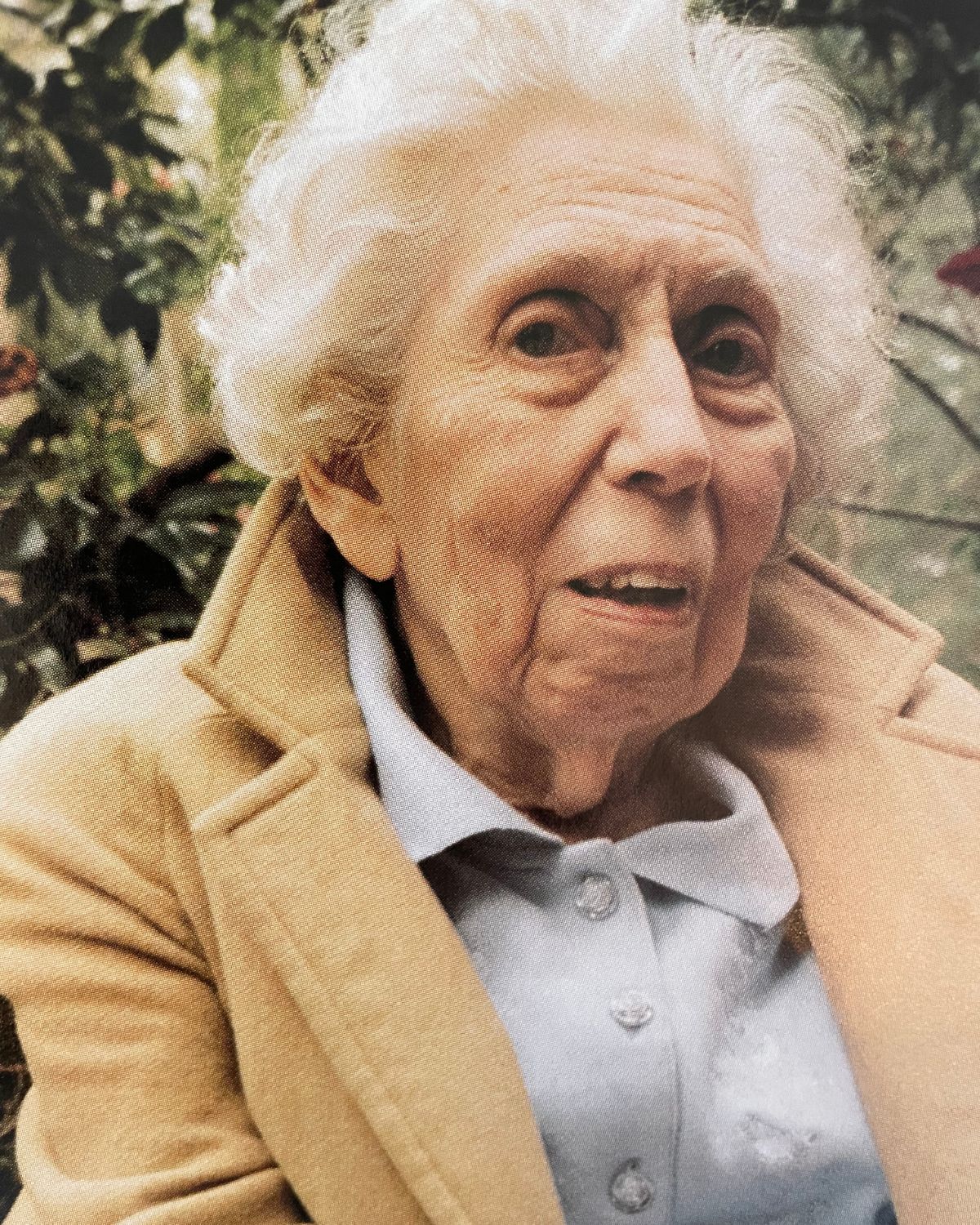

Women We Love: Eudora Welty

Writer extraordinaire, first lady of the South

By Barry Hannah

Photograph by Maude Schuyler Clay

Editor's Note: This text originally appeared in the Spring 1999 edition of our magazine, in a section called “Southern Women We Love.”

I was certain I was surrounded by ignorant ghouls and ash-faced deacons as I grew up in Mississippi. I had heard the oohs and ahs about Miss Eudora over there in my teenage-ripening town of Jackson (beer, tobacco, jazz, blues, and midnight skank at the Dutch Bar), but I set them aside as the vaporings of schoolmarms, desperate for any positive good in Mississippi, which was then essentially South Africa enclosed by a paper curtain of seg newspapers and pastoral chant, pro status quo, from the pulpits. I was very Beat, trying badly to be an angel-headed hipster searching the night streets for an angry fix of howl, but with barely an urb—Jackson, simply wide and country—to do it in. I thought I knew all about the imagination, which, for one thing, could probably only happen in New York. (I’d been once to the Beatnik Gaslight Café on McDougal in the Village and was still reeling from the cool—poets hollering over my coffee, big cup of grown-up, way-out depressed coffee—but of course I knew only anger and the Big Pose.)

When I went up to writing school in Fayetteville, Arkansas, they were still talking about Eudora Welty, some of the hip dude brethren, too, not just your local-color culture vultures. So, also, I was deeply attuned when one of my heroes, Henry Miller, was reported to have visited Miss Eudora to give his respects. Miller in my hometown, old grumpy mushmouthed Jackson? So I read “Powerhouse” and “Death of a Traveling Salesman,” and found I knew little about the imagination. How could a woman, for God’s sake, put the tune to such a jazzman and his nemesis, Uranus Knockwood? (Such was my male bias that I also read five stories by Flannery O’Connor and was raving about him, when someone politely clued me in that the author was a woman. I was getting to be a bigger fool in school every day, which is maybe the point of a good school.) So I shut up and listened. “Death of a Traveling Salesman” was another act of soul-traveling magic—the way Welty was in the man here, his sick loneliness; the way the mule sticks its face in the window and looks at him; his sudden recognition that the woman is pregnant and not old; the shock of his loss of love and simple communication, such as this country marriage represented! The metaphysical inhabiting of another soul, of another gender, and of such an alien order to herself, the artist. How could this be possible? My own father was an insurance salesman; I thought I knew the breed. Beyond mere empathy, or even negative capability—per Keats—these acts of art were simply genius. I had finally looked at genius straight-on, and it was frightening.

There was much work to be done, maybe too much, to be even a water boy on the team of this genius. So I scrapped it all and, feeling humble, began to write the first good stories of my life. I was not ashamed of my state’s people anymore. I had not looked nearly deep enough. Ms. Welty taught me a lifelong lesson. Good things can come if you shut up, watch, and work. She dismissed from me the phony arrogance of the Beat stance and got me closer to a view of the intense life I had sought in my younger scribblings.

I’ll be thankful always for the extra life she made available to me and to all of us.