Through the Past, (Sort Of) Darkly

A fast-food toy and time regained

By Paul Reyes

Photograph by John Margolies. Courtesy Library of Congress

My mother keeps the small relics of my childhood in a plain, brown box, in a closet, in a room touched-up with religious attention to the past. Framed pictures of my adolescence crowd the bookshelf, which holds all the books I’ve given her and a familiar pile of high-school yearbooks best left shut. The furniture itself isn’t boyish, but ragged stuffed animals still populate the bed and corners. My mother’s love is untiring, unsubtle, and the room shows it, as if my adulthood has been a long, dragged-out sabbatical from the paradise of being nine. Each visit home, I’m led through the embarrassing ceremony (there’s a rhythm to it): She points to the animals, she admires the portraits, she goes for the box.

She prizes the toys especially. She cherishes the stuff, whatever little objects that entertained me that I didn’t lose or throw away. None of the toys are all that special or collectible. Most are damaged. I think she may have simply noticed one on the floor now and then, somewhere in the house, and impulsively grabbed it and put it away. I remember them, but I don’t remember them missing.

Recently she conspired with my grandmother to consolidate the relics (my grandmother had her own collection). More toys were mailed over, tossed in the box. My mother waited. I visited again, and inevitably we picked through: a stuffed rabbit (never was crazy about it), a wind-up chime (lullaby variety), a quarterback action figure (double-jointed), and some matchbox cars, mostly unremarkable.

Except for one, a Hardee’s matchbox racer, a white Camaro replica that caused a shudder when I saw it, and that when I picked it up drew the wild sap of childhood out—the past revisited, all at once, the Proustian shock. It didn’t just remind me of childhood, but tapped its emotional dimensions. I held the car up close, and flicked the wheels, and peeked inside, and the scale and scope of the world were recalibrated to when I was young. This feeling, if you ever get it, is an opiate, and of course fleeting.

The Camaro itself is a chintzy thing my father gave me when I was a boy, with paper-clip axles and the number 90 stamped in orange on the roof and doors, the name HARDEE’S stamped on the trunk. On the doors, too, is etched the name ROAD RUNNER, which seemed to give the car a goofy personality, like cousin to Kitt or the General Lee. Held up off a surface, its tiny wheels droop; across a surface, they catch instead of spin. The scars and scratched paint prove I was rough with it, staging all kinds of wrecks at 1:64 scale. But what, exactly, were the scenes? All that comes to mind now are dizzy, impressionistic pulses. I’ve studied the toy to death, drained its surprise, and I’m left mostly with a big truth it has shaken loose: Fast-food restaurants, for all their ills, are the dreamlike sets on which time with my father is locked. They are how I got to know him. He built them— Hardee’s, Wendy’s, Burger King, Kentucky Fried Chicken—all over the South, and he loved it, and I inevitably got sucked into this enthusiasm, and their creation, by virtue of the fact that I was around, that I was his son, and in a father’s steps a son follows for a while, even if at a distance. As backdrops they’ve become nostalgic, though I would have been loathe to admit it until now. Hardee’s, meanwhile, remains the Oz among them, a source of wealth and suffering and confusion evoked by this matchbox racer, somehow resurrected by my mother’s powers from my nervous childhood, from the last years I spent at all with toys.

Hardee's came into our lives—rather, we entered its domain—in 1981, when my father was hired by its largest franchisee to build or fix as many as it could fit into the fold. Both Hardee’s and my father’s employers, Boddie-Noell Enterprises, were headquartered in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, just a town of forty thousand, segregated, and painfully quiet compared with Atlanta, the city from which we’d moved.

My father arrived at his profession by accident. Fleeing Cuba in 1960, at the age of fifteen, he landed in Miami and chased work all the way to Philadelphia, where he met my mother, had me, went to night school, and returned South again with an engineering degree and the skills to win a job with the tragically named and briefly successful Sambo’s restaurant, a family diner launched out of California in 1957. The owners, Sam Battistone and Newell Bonette, had made the apparently innocent but still gaudy compression of their names after discovering Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo (1899), in which the book’s young hero takes a walk through the jungle, and is bullied by tigers who rob him of his clothes. The tigers then come upon one another and proceed to wrestle until they’ve all melted into butter, which Little Sam’s father, Black Jumbo, discovers on his way home. He gives the butter to his wife, Black Mumbo, so she can cook with it. “Now...we’ll all have pancakes for supper!” she says, and prepares pancakes “as yellow and brown as little Tigers.” Father eats 55 pancakes; mother, 27; Little Sam downs 169. End of story.

I can’t imagine even in 1957 this being a reasonable premise for an American business, but it worked, and by the time my father joined the company in 1976, Sambo’s had over a thousand restaurants across the West Coast and Southeast, with pancakes, of course, as a house specialty. At one point, he oversaw construction of every Sambo’s east of the Mississippi, and can brag, I suppose, of having built 240 of them in a single year.

My father still had some contextual gaps in his English, and didn’t know what kind of taboo the name was; but as these diners arrived in the Northeast, as he put it, “we caught hell.” He would take phone calls from panicked foremen in Weehawken, and Manchester, and relay the emergency to headquarters in California, at which point a spokesman would be dispatched to settle whatever picketing and protests the name had ignited. Finally, when the Security and Exchange Commission investigated the company for its accounting practices, my father began to look elsewhere for work.

He answered an ad in the Constitution, and drove to Rocky Mount for an interview. His first impression of the town was accurate: it was dull. (Its only prestige, I think, is as the birthplace of the great Thelonious Monk, whose family left well before he could remember it.) The interview was a success, and afterward he was invited to a company picnic on a company farm. The evening was cool, music played, and people danced half-drunk, beehiving around a roasted pig that lay steaming on a table in the open field. This was, he told me, the first pig roast he’d been to—the first pig he’d seen at all— since his boyhood in Cuba. I like to think this was his first nostalgic slip; the moments mirrored each other. So he peeled the meat from his old favorite parts. The homecoming spirit was all around him. The town, and these people, had won a sentimental grace. Two weeks later, we were moving in.

My father was a workaholic before we knew what to call it. He binged on paperwork during the week and on weekends cruised all over the Carolinas to inspect the Hardee’s sites under his charge— new projects and remodeling jobs in towns where a Hardee’s grand opening drew a pretty good crowd, and where each restaurant became an outpost of social life. He regretted all the time he’d spent away from my mother and me in Atlanta, but was no less busy now. His solution was to combine his devotions to work and family, to bring us along on these weekend inspections. I was drafted first. Later on, my mother followed. This was my father’s awkward way of bonding. We didn’t play sports, we didn’t fish. We went to Hardee’s.

You can bet it was miserable. Think of all the sunlit days I would have rather spent burning something, or riding a bike. Instead, I stretched out in the back seat, read a book, watched the countryside, or stared up at the dappled sun. We talked, of course, but neither of us remember the particulars. We only have the visceral memory of different moods: his excitement vs. my gloom.

The ritual involved some deceit. He’d ask me to come along with him for a short ride, an errand, and we’d run that errand, but then continue on out of town toward Tarboro or Wilson, about ten, twenty miles away. Once there, I’d watch him converse with strangers and point and tell others what to do. If the Hardee’s in question was open, we’d eat there; if it was still under construction, we’d stop and eat at one on the way. Or we’d eat at each inspection.

Still, the trips were dry affairs, time a treadmill, and so I eventually sought refuge in my mother. She was a useless shield, though; my father simply brought her with us. She had trouble refusing, since she didn’t fit Rocky Mount at all—its racial homogeny, its slow pace—and any excuse for her to leave town seemed a relief. A Colombian immigrant, she’d left a good job in Atlanta, and couldn’t find a similarly good one in Rocky Mount. Meanwhile, among her circle of friends, housewifery was the thing. So my mother followed suit, killing time with racquetball lessons, accounting classes, shopping, decorating the house my father eventually built her (an extravagant penance), and keeping tabs on me.

Whenever I press her for details of those years, I do so with a little guilt, and gently, since it forces her to recall a boredom so profound it likely touched existential edges. And no matter how I try to upgrade the past, she sees it as five years wasted.

Two stops, then a third, as many as five. They became long, dull patrols; the day seemed elastic. And there was only so much fast food I could eat.

The trips stretched into Virginia—Roanoke, and Petersburg—and west to Thomasville. Just getting near the car with him was a risk. The sounds of his preparation—the click of pens and pencils, rustling through his briefcase, the trill and snap of a rubber band on rolled-up blueprints—all announced a road trip. I’d hear him warming up and find a room to hide in. If he found me, I’d refuse. He’d promise the trip would be short, and fun, and outwit me. Or he would plead. Or he would demand that I come in a tone that erased any choice. Mostly, though, he preferred the ruse, and I remember his laughter the moment I’d realize—seeing Highway 64 in the near distance, or seeing, too late, that we’d glided onto a stretch of road along which the signs of town were thinning—that I’d been duped into another trip. I’d moan, and he’d laugh from the belly at my finally being in on the joke.

He felt grounded in this ritual of bringing me to work, since it reminded him of his own youth. His grandfather, a Spaniard whose name my father was given, made his wealth in Cuba selling soda crackers, of all things, and he put my father to work early at the bakery, and even enlisted him in various construction projects he had going on the side. Just a boy of nine, my father carried tiles for the roofers, pushed trash in a wheelbarrow, stacked bricks, that kind of thing. He idolized his grandfather, and so he was thrilled to work for him. This pastime stalled with me, though. Oddly, my father never put me to work, at least not at the age at which he’d started. Instead, I spent a lot of time snooping around, sneaking between joists, staring up at the delicate parts of a drop ceiling, the wire and framing that hid the building’s electrical guts. I dodged the carpenters. I fiddled with sawdust and odd, lopped corners of two-by-fours. The noise of these sites was at first horrible, too hectic. But you got used to it, and the hammering and shrill saws sang a warmth in all that clatter.

I’ve often turned to my parents to help me rummage through what I’ve forgotten about our life together in Rocky Mount. My mind is so weak on the subject. But to believe them is to balance two different emotional truths, both of which color the answer to what my childhood was like. My father remembers Rocky Mount more fondly, mainly because of our trips; he also possesses a talent for gently refusing regret—or, at least, internalizing it. My mother, though demure, is more blunt (“Boring doesn’t describe it.”). To her, the town sucked, and that’s that. The result is a confusion of loyalty, so that choosing an attitude toward my childhood is, in a way, choosing sides. Who to believe? It depends on my mood or state of mind.

Until recently, I would’ve argued that memory’s factual solace is in photographs, by which we can read the inner weather a face suggests, and confirm that we did a thing, that we were there. But by their exclusion photographs are also deceptive. Until the matchbox racer, I hadn’t realized just how sloppy my memory of these road trips had been. The long afternoon drives with my parents always seemed like their own events. Recently my mother corrected me, though, an uncomfortable revision: By bringing her along, my father had simply expanded our ritual; my foggy visuals of the three of us on family vacations are actually, at least in part, trips to Hardee’s.

The strangest of which was a Christmas with an uncle in Richmond, a trip my parents say included several stops at Hardee’s along the way. I wore contact lenses then, a vain torture, and had worn them well too long that day, but apparently, out of some foolish hygienic paranoia, refused to take them out at any of the Hardee’s we visited. I waited instead until we reached my uncle’s home. My memory kicks in right about when we pull into Richmond, when my eyes had finally dried up. The lenses had scratched my pupils, and after a brief trip to the emergency room I arrived at my uncle’s with bandages on my eyes (they’d heal on their own if kept shut). So the photographs of that Christmas include a blinded, bandaged boy with painted eyeballs—opening gifts, banging on congas, slumped on the couch. The camera flash startled me all weekend (an easy prank). Of course, I remember the details of that blindness better than I remember any of the Hardee’s we visited on the way.

Working for my father was inevitable, if not because he was eager to instill in me the values his grandfather had taught him, then for the simple fact that, with his work ethic, my idleness drove him nuts. But he waited a while, and didn’t put me to work until the summer I turned fourteen, in Florida. Hardee’s was behind us by then, and he had started his own small construction company. My first job for him—my first job at all—was to pick a friend who could help me remodel a Wendy’s my father promised was “on the beach.” I expected sweet rewards from this gig: the serenity of the Gulf in summer, girls walking past and catching glances, and, of course, a right to proudly tell others that I, so unmasculine, “worked construction.”

The site was near water, sure, but its proximity to the beach was a matter of interpretation. Near the beach in spirit, maybe. About a mile from the sand and over a bridge. Yes, girls drove past on busy Pasadena Boulevard, but we only spied them through the windows from inside.

The site itself was a disaster: arson, though the fire never left the kitchen. Still, every inch of ceiling had been blackened by the smoke, and the carpet oozed water and a thick humid stink of burned metal, burned grease, burned wood, burned wires. The fire had been put out just the night before, I think, because there was still half a foot of water in the kitchen; the grease in the deep fryer hadn’t even cooled enough to congeal.

Our job was to clear all the ruined equipment from the kitchen, tear the carpet out, remove the ceiling panels—a somewhat careful demolition—after which the interior would be built all over again, a strategy that was supposedly cheaper than rebuilding the Wendy’s altogether, a calculation that seemed absurd just by looking at this alien mess we had to wrestle with. I remember the awestriking impossibility of that kitchen. A hole in the ceiling was the only light. Pipes dangled. We were in the guts of a blasted ship.

We hauled for two weeks, grabbed any piece of the kitchen that could be moved and tore loose what was stubborn and dragged it all outside and heaved it into a rented dumpster. The heavier stuff, the ovens and such, were considerable trouble. But somehow we did it, and in thirty days the Wendy’s was open again. Afterward, I bragged about my first work-related injury, a nail through the foot.

I felt as much joy throwing firecrackers into the sewer as I did in a McDonald’s playground.

The next year, I had a chance to avoid construction altogether when my father surprised me with a job at a nearby Burger King, arranged between himself and a manager, whom my father introduced me to while eating there, during another one of our errands. That was how I found out about the job.

What I saved in sweat I suffered in humiliation, as anyone who has worn that shackling polyester uniform and has served others on the outside can attest. It was as if the uniform itself was designed to spread pimples. And as working environments go, fast-food kitchens have the spirit of a jailbreak.

This job was too painful. I quit after two weeks, but not before making one friend, Laminka, who shared her breaktime with me, and about whom the most vivid detail I’ve kept is the criminal amount of ketchup she dumped onto her fries—two handfuls of packets. I thought it was some weird compensation for our poor wages.

I also made an enemy, a long-haired boy whose final gesture was to request a fight. A coworker relayed the details: I was supposed to return the next day, when the angry one was working, and meet him by the dumpster. I only remember the green uniform of the messenger, not even his face. “But this is my last day,” I told him. “Right,” he said, sympathetically, “but he wants you to come back tomorrow anyway, after his shift, and then he can fight you.” I missed some important code here, and could only laugh, baffled. The messenger shrugged. In piecing this together, though, I think I’ve figured out the motive: My father had gotten me the job through his connection to the manager, which automatically made me a pet; also, I didn’t own a car then, and often had to borrow my father’s, a brand-new white BMW 635 csi, low and long and slick. This car appeared just after my mother divorced him, and it helped him rally against the mid-life crisis the divorce must have brought on. He was only thirty-eight, but alone. I assume the car must have helped him, though I never saw him with a woman in it. Meanwhile, I looked ridiculous driving it, never mind driving it to work. In retrospect the math seems simple: bird-boned, pimply manager’s pet, in full Burger King uniform, with visor, pulls up in a German-engineered chick magnet, a muscle car with a nose like a leer jet, to his job at said Burger King. There was cruelty in this, for sure. Even I would want to beat me up.

I returned to the more dignified labor my father offered the next summer, and would continue working for him—after college, after graduate school, between other jobs, between phases of a stuttering adulthood. Eventually his company faltered, and he simplified his life by remodeling decrepit houses, getting dirty, the hands-on work he enjoyed as a boy. Somewhere in his resume is a KFC he built in thirty days, a record he cherished until another company broke it the following year. Our last fast-food job together was our proudest, again a Wendy’s. This time the assignment was to install a salad bar, a weak trend of the late ’80s that introduced health consciousness to the fast-food menu. The job was a furious all-nighter, and really the most fun I’ve ever had as a laborer. Any customer who was the last to leave Wendy’s that night, and sadly loyal enough to return for lunch the next day, would have seen it radically transformed. Out went the eight-foot, oak-and-stained-glass divider, and, with the power of jackhammers and torches and a dozen hands, in went the future— salad! As far as I can tell, all those salad bars are gone now.

For all the imagination that has gone into the Saturday-morning campaigns that promote fast-food restaurants as places of warmth and homecoming, the only emotions I could attribute to them growing up were boredom, frustration, humiliation, and, once we were old enough to prowl the parking lots after midnight, lust and fear. I never felt joy or true pleasure in a fast-food restaurant. Being young doesn’t count. I felt as much joy throwing firecrackers into the sewer as I did in a McDonald’s playground. And fast food, for all its power, possesses none of the nostalgic potential of, say, your mother’s cooking, or even your neighbor’s cooking. Generally, fast food is designed to remind you of itself, to be experienced in a kind of vacuum of junk pleasure. If not for my father, fast-food restaurants would be easy to ridicule. They still are, in many ways. But they also have become complicated figures in my imagination. I can resent them as health hazards, or as a cultural plague, but as works in progress they are tied to patrimony. I would have preferred baseball, I think, but you take what you can get.

Meanwhile, memory is deciduous. A mess is made of a mind’s handsome bloom. Even guided by handed-down anecdotes and photographs, those years in Rocky Mount remain irritatingly vague. I sieve the particulars with the help of my mother and father, their competing impressions of the same experience, their rival truths. In a way, our three positions form the points of a plumb that tilts between versions—his, hers, and mine tipping back and forth between them.

Trolling helps. I’ve been clicking through eBay in search of other familiar toys—action figures, Hot Wheels, Smurfs, etc.—with the gloomy pleasure of an afternoon at the aquarium. Somewhere lies another trigger. This online rummaging is dull, though, nothing like a real physical discovery. You cannot hold the toys, only recognize them, all photographed in such bad light.

Nothing like a toy in hand, which leads to one last confession: There were two matchbox racers in my life then, the second of which I found toward the end of writing this. The second is caked in white-out, like white rashes where the orange details should be. I don’t know how I missed it the last time through the box, but when I finally did grab it, I flashed briefly back to my white-out phase, around the age of ten or so. It started with corrections to misspelled words, all well and good, but then got away from me—this impulse to repair or erase traces of where I’d been—and white-out would end up on a wall where a black streak had marred it, or on white toys if they’d been damaged. The habit warped into using white shoe polish, the Kiwi bottle with the sponge applicator, to cake my sneakers in white. I can’t say whether simply washing them had occurred to me. To this day my parents have no recollection of this habit, though I distinctly remember how noisy and stiff the sneakers were once they’d dried.

I’ve already celebrated that I was a strange kid, but what kind of revelation is this? What does a whited-out toy suggest? What psychic forces shoved this thing to the surface? I wonder, too, why my mind requires such jolts to call up these strange phases. I don’t think it’s a repressive condition, not yet I don’t. No, as far as I can tell, it’s the wiring.

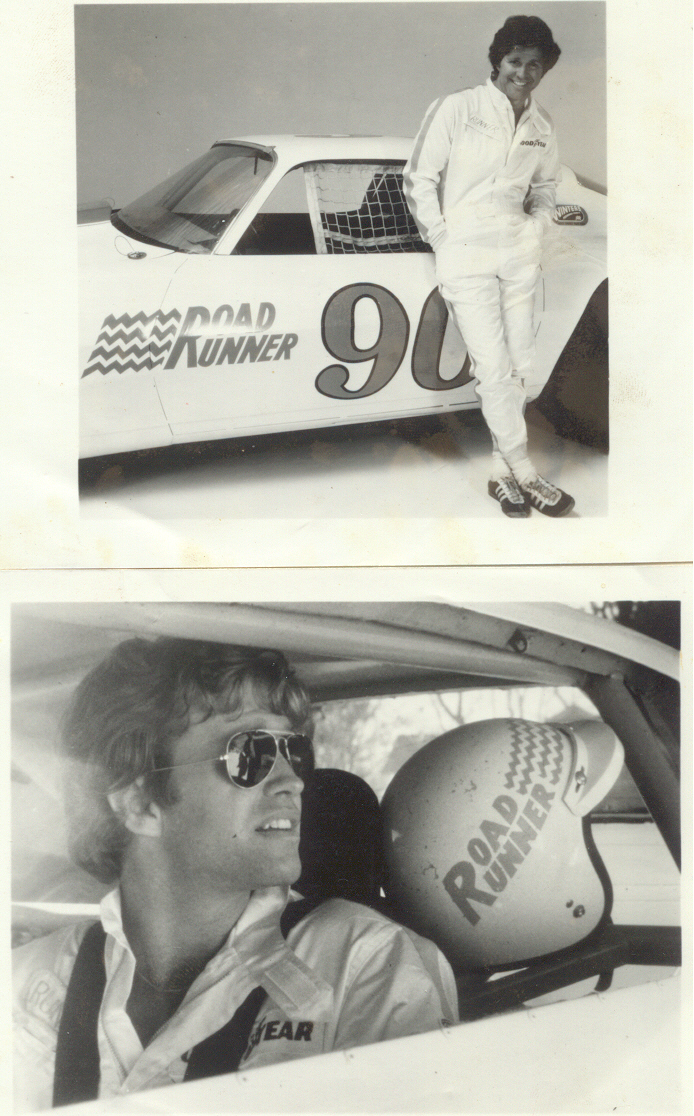

AUTHOR'S NOTE: Not even my memory of the toy that triggered this essay is entirely accurate: The Road Runner, it turns out, was alive, a breathing creature, an actor in a silver jacket. It was a character’s name, not the car’s. It blew my mind to learn this big detail, accidentally, from my father, whose simple aside—“I met him”—once again revised what I thought I knew about it, there, us, etc.

Image courtesy Jeff Lonto and Studio Z-7 Archives

So I looked it up: The Road Runner was a marketing idea aimed not at children, but at adult NASCAR fans: A stock-car driver with a losing record, the Road Runner, played by a soap-opera star named Phil MacHale, would stop and eat at Hardee’s between each humiliating race. For four years and about a hundred commercials, The Road Runner and his mechanic sidekick, Ernie, tapped the Dukes of Hazzard vibe, and enjoyed a cultish regional celebrity. I remember absolutely nothing about these two, or the commercials; no surprise there, since the target audience was likely still hungover in bed during my Saturday-morning time slot. Still, in asking around about them, its uncanny to learn how wildly popular the Road Runner was. He attracted long lines of women at Hardee’s grand openings, women who waited patiently for his signature, or to kiss him, orjust to flirt up close. He was popular even at the actual NASCAR races, in a kind of art-imitating-life-imitating-art surreality. He would drive a lap and fans would cheer him on like he was Bobby Allison, or Cale Yarborough. Women, it’s true, would scream. For a brief time, the Road Runner was a stud. Chances of having seen either actor since this glorious run are slim, though. Their fame peaked with Hardee’s, and only the Ernie the sidekick got as far as a quiet career as a Hollywood journeyman.