Tangled In Wishes

By Kevin Brockmeier

There are songs that have saved lives, and songs that have ended them.

—Joshua Poteat

It seems to me that those of us who aren’t musicians usually take one of two imaginative stances toward the songs we listen to—either we imagine ourselves as the singers or we imagine ourselves as the sung to. I am one of the sung to. When I concentrate on a song, it is as if someone is speaking directly to me, unreservedly and in total privacy. The voice that comes through my speakers strikes me as faraway, inaccessible, and yet somehow strangely intimate. Perhaps it is this presumption of intimacy on my part—a false presumption, I know—that makes certain tones so likely to set my teeth on edge: vanity, pugilism, boastfulness.

“Then you don’t like rock & roll,” a friend once told me when I confessed as much to him.

And I thought, Maybe so.

It’s certainly true that I am out of sympathy with the main currents of a lot of rock music. I am constitutionally averse to swagger, unless it’s delivered with a wink and a shrug, as if to say, “You and I both know that I can’t really pull this off, but let's pretend that I can.” In other words, nerd-swagger. And I am generally unmoved by the aesthetic of transgression that has energized so many rock bands, from the Who and the Sex Pistols down through Nirvana and the White Stripes. It’s not that I disrespect it; I just don’t find it very interesting, although, for the sake of completeness, I should say that most of it strikes me as fairly reflexive—little more than transgression for transgression’s sake—and I tend to respond with more engagement to what I hear, rightly or wrongly, as heartbroken, principled, or playful transgression (see, respectively, Arcade Fire, New Model Army, and They Might Be Giants).

Once the basic elements of form and melody are in place, what I look for in a piece of music are vulnerability, openness, and purity of tone, along with enough precision or passion of delivery to keep me from becoming embarrassed on behalf of the singer, a feeling to which I’m all too prone. Beyond that, I”m after the same sensation I’m always after, both in life and in art—the sensation that I’m being presented with something that has been cherished by someone. In an essay about William Maxwell’s short, masterly novel So Long, See You Tomorrow, Charles Baxter observes, “[Y]ou feel that you have been given considerably more of what is precious to its author than is often the case in novels of many hundreds of pages. What Maxwell has loved, he gives away in that book.”

And ultimately, that’s what I want from a song: a feeling that I’m being given what is most precious to its singer. Offer me that, along with a voice capable of delivering the message, and you’ll win me over every time.

Which brings me to Iris Dement, and to My Life.

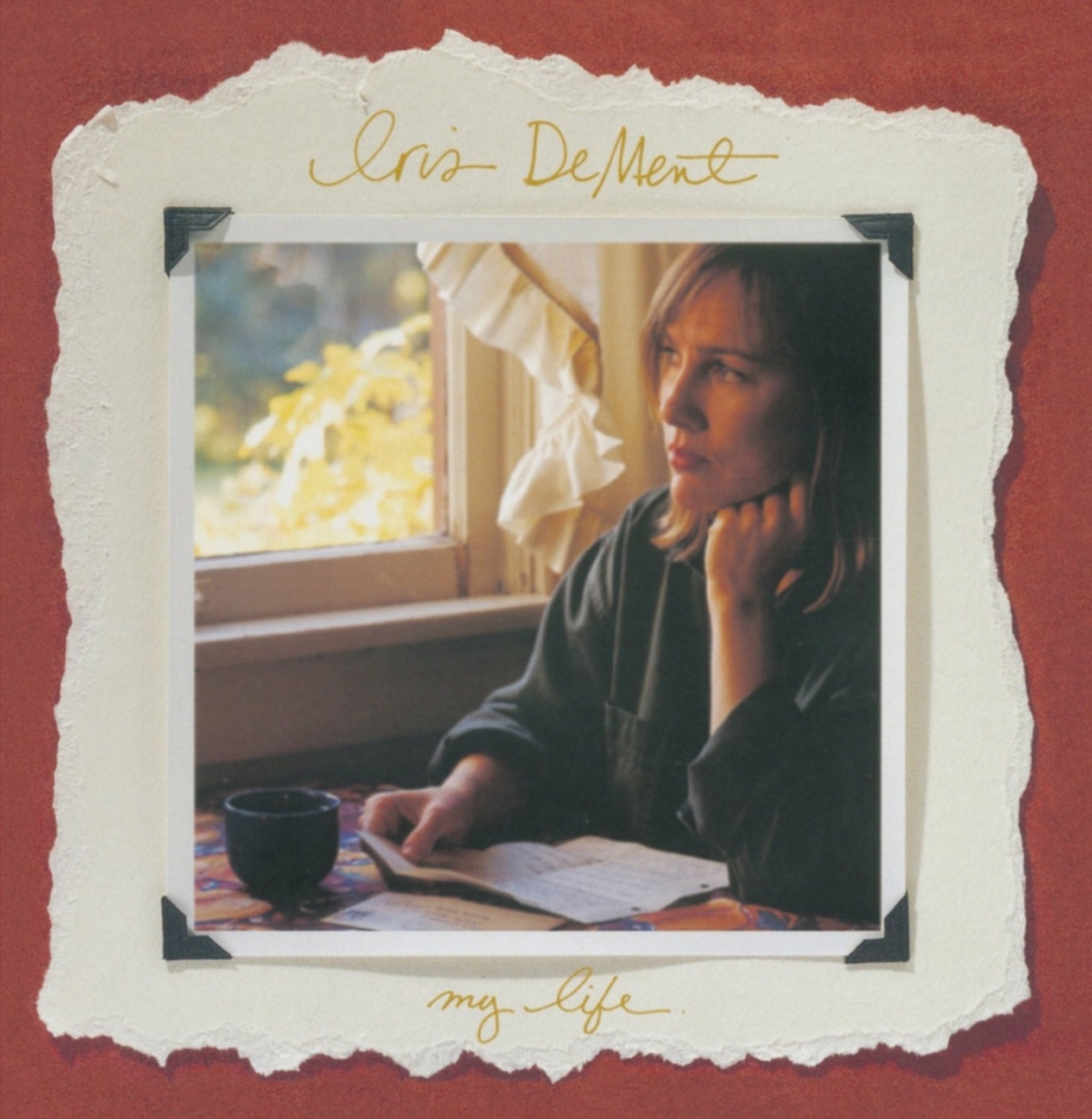

My Life is the second of three albums of sweetly flowing country-folk songs that Iris DeMent recorded in the mid-1990s, following the poignant, confessional Infamous Angel and preceding the slightly more outward-looking and studio-lustered The Way I Should. Since then, she has remained largely silent, though in 2004 she returned to the CD bins with an album of gospel standards—and one original—called Lifeline.

Each of these albums has its treasures to offer, and indeed many of Iris’s fans have found the warmth and tenderness of Infamous Angel, her debut, to be unsurpassable. For me, though, My Life has proven the richest and most enduring of her recordings. An intimate suite of heartache and yearning, lightened only occasionally by the kind of airy happiness that presents itself as a necessary-but-never-more-than-temporary renunciation of its own grief, it is one of exactly two albums I own that I wouldn’t hesitate to call perfect. (The other is Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, which strikes me as My Life’s reverse image in many ways: an album that celebrates without ever denying how much there is to mourn in the world, whereas My Life mourns without ever denying how much there is to celebrate.) When I say that I consider the album perfect, I mean that I can’t imagine what change might be made to it that could improve it. Not a single moment seems anything less than moving, honest, and inspired: no lyric, no vocal flourish, no shift in rhythm—nothing. The effect could easily have been ruined in the studio, but the album’s producer, Jim Rooney, who also collaborated with Iris on Infamous Angeland Lifeline, appears to have understood the demands of the material so thoroughly that he was able to provide Iris the best possible natural cushion for her melodies, so that when you listen to the album, it very nearly sounds as if everything has arisen spontaneously out of her own mind. This is no small accomplishment, particularly on a work of such interior and often wistful sensibilities, exactly the kind of album frequently saddled with a wrongheaded production strategy—cluttered, bombastic, glossy, or simply unimaginative—that turns the whole thing to mud.

In my experience, the perfect song, like the perfect short story, isn’t all that unusual: there are many of them, and they lie relatively common on the ground. But the perfect album, like the perfect novel, is like one of those strange translucent creatures from the bottom of the ocean that are rarely ever seen by the human eye. It is nothing short of a miracle when one of them manages to make it to the surface alive.

Ordinarily, I’ve noticed, when critics write an essay in praise of an album, you’ll find them offering at least some hint of an adversarial relationship with it, designed to stand as a signal that they’re volunteering their honest, sophisticated response to the material. I’m a fiction writer, though, not a critic, so I’m resisting the temptation to contrive such a hint. My honest response to My Life—sophisticated or not—is simple adoration, complicated by nothing except my initial slight resistance to Iris’s singing voice. For although, as must be obvious, I have become something of a missionary for My Life over the years, it took me several listens to appreciate it, and even longer before it found its place as one of the landmarks in my personal musical pantheon.

In 1994, when the album was released, the big-box record stores had yet to make their way to Little Rock, where I live, and most of the independents had already shut their doors. The Internet was not the vast library of MP3 files it is today—or if it was I had never taken the time to investigate it. Thus, I had never heard so much as a note of Iris’s music before I picked up a copy of My Life. This was something I did frequently when I was in high school and college, sifting through the racks at Been Around Records or Camelot Music and buying an album I was totally unfamiliar with based on little more than the cover art or the song titles, the record label or the name of the band. By this method I discovered a whole host of mostly forgotten mediocrities—though I’m sure there is somebody out there who loves the Bambi Slam, I don’t—but also a number of performers I still listen to today, like the Jean-Paul Sartre Experience and Billy Bragg.

The first time I put My Life on the stereo, I responded with pleasure to the melodies, the lyrics, and the general character of the songs. There was a hitch, though: I wasn’t sure what to make of Iris’s voice. It is as clear and unpolluted as any voice you're ever likely to hear, washing through the instruments like a warm Southern stream, but its timbre is unusual. The way it lifts up so ardently from the bed of the music, swaying along with the fiddle or the accordion, and bowing out around the vowels— well, it takes some getting used to. Moreover, I don't imagine you could enjoy any of Iris’s albums without also enjoying her voice. The same could be said of any number of performers whose music I happen to appreciate: Tom Waits, Bill Morrissey, Joanna Newsom, Jeff Mangum—all of them are polarizing vocalists. Iris is unique among them, however, in that both the people who adore her without qualification and the people who bristle at the very sound of her will point to her voice in explanation. Her voice is, quite simply, where the personality of her music lies, and unless it speaks to you, nothing else she does will register.

It took me a few listens to grow comfortable with the way she sings, but when I did, I quickly realized how expressive her voice can be. It is capable of carrying so much exultation on the one hand and so much sorrow on the other, with so little costumery or ornamentation, that it can seem as if she has lived an entire life inside every note she delivers. And yet her vocals are always crafted to lend attention to the song rather than herself. She happens to sing well, but beyond that, she sings with the unmistakable stamp of experience, hard-won and cherished, so that the overall effect of her music, no matter how sad it becomes, is cleansing, invigorating.

It has always seemed to me that the best singers are the most evocative ones, which is a separate consideration from how conventionally pretty their voices might be. What’s more depressing, after all, than those technically proficient, million-selling singers from whose tongues every trace of honest emotion has been extinguished, until there is nothing left of their songs but grace notes, one after the other, lined up on all sides of the melody like birds pecking at a chunk of bread? The songs on My Life are exactly the opposite of that. They are powerful in their simplicity, and Iris’s voice flows naturally, right down the center of their melodies, just as it should.

I recognized all of this within a few weeks of first listening to My Life. Right away, I began including selections from it on the mix tapes I made for my friends, particularly the plaintive piano anthem of the title track and the expansive and sublimely elegiac “No Time to Cry,” Iris’s meditation on the loss of her father. It was several years, though, before I truly found my way inside the album.

Just as most romantic relationships are founded on one ideal evening that is preserved in the memory of everything that follows, most artistic relationships are founded on one ideal moment of appreciation, an ideal reading moment for a book, or viewing moment for a movie, or listening moment for an album. In the case of My Life, my ideal listening moment came some five years after the album was released—on Monday, July 5, 1999, one of the most uncomfortable mornings of my life.

My friend Lewis and I, both of us living in Little Rock again after a few years away at college, had driven up to Fayetteville for the weekend to visit an old high school friend of ours who was slowly finishing up his degree at the university, taking a half-dozen nonchalant credit hours at a time. Our only design for the trip was to sit around and catch up with him, maybe firing off a few bottle rockets after the sun fell on the Fourth, but when we reached his house, we found that he had already made plans for us to float the Buffalo River with him, which is how we ended up clustered around a campfire on Saturday night with his fiancée and seven or eight of their buddies. It was the first time in several years that I had been with a collection of people who seemed to understand one another’s rhythms and fixations so well, and I was struck by the ease with which they settled into a pattern of communication, trading one-liners, anecdotes, and inside stories, and every so often, to bridge the silence, asking questions about the condition of the river. Once in a while I have surprised myself by intuitively finding my place in such a group, but that night I felt like I usually do when I'm surrounded by people I don’t know very well: like a mediocre swimmer dropped unexpectedly into the Pacific. Mostly I just listened, waiting for my chance to throw out the occasional remark and watching the embers vary their configuration in the fire.

There was a beautiful girl in the group, with a long rope of red hair falling down her back and a smile that was broad in the center but tight at both the corners, as if it had been fastened together there with two small buttons. At one point I took the chair next to hers, but that was as brave as I could be. I sat beside her uncomfortably for a while, unable to break the stillness, opening my mouth from time to time as if I were about to say something and then closing it again, and when someone reached around from behind her to pat her leg and ask if she wanted a beer, she let out a gasp, believing for a split second that I had suddenly touched her.

It was past midnight before we retired to our tents. The people in the adjoining campsite were listening to pieces of a Tina Turner Greatest Hits album, "Let's Stay Together," “Private Dancer,” and “We Don't Need Another Hero” cycling through their speakers in an endless loop. Two of them were having noisy sex in the tent directly next to mine. I waited a long time for the sounds to die away before I fell asleep.

Just before I faded out, I heard someone complain, “Tina Turner sucks.”

Tina Turner doesn't suck, but having to listen to “Let's Stay Together,” “Private Dancer,” and “We Don’t Need Another Hero” over and over again does.

I woke just as the sky was coloring up, crawling out of the tent to stir through the remains of the fire with a stick. The ground beneath my sleeping bag had been terraced slightly on one side, and though the difference between the levels had seemed inconsequential at first, now I felt as if I had spent the entire night trying to keep from tumbling off the edge of a precipice. I was listless. My muscles were sore. I would have been happy to stay in the campsite reading all day. But after everyone else woke up and began heading down to the river, I became embarrassed remembering how oddly I had behaved when I was sitting next to the girl with the red hair the night before, the nervous gasp she had given when she thought I had touched her, and I imagined that maybe I could redeem myself if I tagged along. I borrowed someone’s sunscreen lotion and grabbed the middle seat of one of the boats just as it was launching from the shingle.

It was a long day, eight hours of slanting and lurching through mile-long stretches of white water, then floating gradually past sand bars and silver bluffs, sinkholes and wooded hillsides. I was wearing shorts and a T-shirt in lieu of a swimsuit. Since I didn’t want my shoes drenched with river water, I had decided to go barefoot, and whenever we stopped to rest, I would pick my way delicately over the burning rocks along the shore and the slippery moss that papered the shallows. As the sun moved inch-by-inch across the sky, my arms grew tired. My mouth dried out, and my head began to swim. The same disease of silence that had overtaken me by the campfire engulfed me once again. The reflection of the light off the water seemed to get into my eyes and bleach the color from everything, making the din on the shore a sallow gray, my skin a chalky white. A plain yellow butterfly rode my arm for the last thirty minutes of the ride, its wings flexing slowly back and forth. I thought about the girl in Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses who has a cloud of butterflies orbiting her body wherever she goes. That was all I could remember about her—the butterflies. The small yellow one on my arm did not fly away until we hitched our boats up onto the gravel at Buffalo Point.

My friend and a couple of his buddies piled into the truck they had left in the parking lot and drove back to the campsite to retrieve the rest of our cars, while Lewis and I stayed behind with the others. Set back from the shore was an old wooden hutch with a concrete floor, and in ones and twos we drifted over there to clean ourselves off or change out of our clothes. I assumed that the hutch was divided into separate compartments, like the park’s restrooms, one for the men and one for the women. But as I made my way to the door, the girl with the red hair came hurrying out, clutching her sandals in her hands.

Inside I found a single open space with streaks of sunlight slanting through the boards. The gaps were wide enough for me to see outside, but the shading made it difficult for anyone else to see in. I had left such a strange impression of myself that she might easily have thought I had been trying to catch her undressed. Would the idea have surprised her at all, I wondered? I wrung the water out of my clothes and toweled myself off, then went to sit with the others at the edge of the parking lot, waiting for the cars to return to Buffalo Point.

As it happens, Iris was born not terribly far from this point—in Paragould, Arkansas, about a two-hour drive to the east. The landscape of Paragould is different from that of the Buffalo, the oak forests and limestone bluffs of the Ozarks fading away to the flatlands of the Arkansas Delta, but the climate is similar, and the summers Iris knew as a very young child must have been soaked in the same buzzing heat as ours was that day. At the age of three, she moved with her family—her father, mother, and thirteen older siblings to Buena Park, California, where several times a week they worshiped at a charismatic Pentecostal church. It was there that Iris first heard many of the old piano hymns she would later record on Lifeline—the same songs she performed on doorsteps and street comers with her sisters and brothers, tambourine in hand; the same songs her mother sang at the upright piano in her bedroom whenever “the hard times came in for a long visit.” Iris left the faith shortly before she moved to the Midwest to begin college, but she continued to feel the influence of the gospel music she had grown up singing, and she still attends services today at a church near her home in Kansas City, speaking admiringly of the openness of the congregation and of the living that comes out in their voices when they sing. She began composing her own songs at the age of twenty-five and released her first album six years later, at the age of thirty-one. One of the earliest tunes she wrote was “Our Town,” the song for which she’s still best known today, introduced to many listeners when it played over the closing minutes of the final episode of Northern Exposure. Her most recent album of originals was released in 1996. In the decade since, she has continued to tour and perform, and though she has written songs, she says, “I haven't written twelve songs that I want to make a record of.” In November 2002, she married the prolific and formidably talented songwriter Greg Brown. (If you don't know his albums, I recommend that you track down either Down in There or Dream Café, which jockey for position as my favorites.) On March 21, 2003, the evening after the U.S. invaded Iraq, she cancelled a show in Madison, Wisconsin, out of respect for those who were suffering the violence of what she believed to be an unjust war. This decision quickly drew the ire of many conservatives, who subjected her to a campaign of hate mail so venomous she was later driven to describe it as “a spiritual assault.” It seems clear that, despite the peerless intimacy of her music, which can make you feel as if you have known her all her life—known her so well, in fact, that you find yourself using her first name when you write about her—she has tried to preserve her privacy, so I will close the curtain on her biography here.

Back in Fayetteville, the day after the canoeing trip, I woke early, my head pulsing with fever. I knew even before I made it to the mirror that I had been badly sunburned. Like a suit of clothes that had been left out to harden into its own planes by the weather, my skin no longer seemed to fit me right. There were mottled patches of red on my forehead, arms, and shoulders, and a large, sharply outlined stain, its color a violent beet-red I had never expected to see on my own body, that stretched across my ankle and onto my left calf. No one else was awake yet. I took my headphones and one of the CDs I had packed—it happened to be My Life—and slipped onto the front porch.

It has always been amazing to me that you can recognize a beautiful day even when you aren’t capable of appreciating it. The sky was a pale, capacious blue. The sun had just begun to wick the moisture off the grass. In my exhaustion, I was more receptive to Iris’s songs than I had ever been before, and as I sat on the stool watching a few early-morning cars coast noiselessly down the street, my head filled with the enveloping hum of the instruments, and I felt my eyes begin to sting. I got lost in the music, people sometimes say, and they mean it as the highest form of praise, but my experience that morning was exactly the opposite: The music gave me definition, made me clear to myself, I encountered myself in it. I thought about how long it had been since I was surrounded by the people I loved best, how easily damaged I had turned out to be, and I was convinced that I was feeling what Iris had been feeling as she performed the songs on the album. I had left so many people behind—too many already, and I was only a few years out of college. I had built and then abandoned one version of myself after another, and I liked the selves I had abandoned better than the one it seemed I had replaced them with, and I was so tired of building. I sat there in the shade of the porch trying not to move against my skin, absorbing the album as if I were generating every note directly out of my own experience, from the gliding contentment of “Sweet Is the Melody” to the high-lonesome ache of “Calling for You,” from the rawboned sorrow of “Easy’s Gettin’ Harder Every Day” to the simple poetry of the title track:

My life, it don't count for nothing

When I look at this world, I feel so small

My life, it's only a season

A passing September that no one will recall

But I gave joy to my mother

I made my lover smile

And I can give comfort to my friends when they're hurting

I can make it seem better for a while

My life, it's half the way traveled

And still I have not found my way out of this night

My life, it's tangled in wishes

And so many things that just never turned out right

The friend I was visiting came to the screen door and spotted me on his stool. He made a tiny hello gesture with his fingers. When my eyes slid away from his, he turned and went back inside. The heat was starting to rise in the air, making my sunburn tighten over my skin. Still, I couldn’t imagine what it would take for me to get up and follow him into the house. I remained there on the porch, letting the music filter slowly into me, until the last note had dwindled away and I could hear the insects chirring in the yard again, the car tires hissing down the street. It seemed to me then, as it does now, that my discomfort and hypersensitivity had somehow fastened me to the music, making it plain to me for the first time, and that the music in turn had somehow fastened me to the circumstances of my life.

I sat in the shade with my headphones resting around my neck, waiting for Lewis to wake up so that we could make the drive back to Little Rock.

I used to be one of the singers. Anyone who knew me growing up will tell you that from the day I learned to speak there was always a tune in my mouth. My mom hated to take me grocery shopping with her when I was little because of the way I made every trip down the aisles a medley of commercial jingles. “Hi-C / Hi-C / It tastes so wonderfully.” “Coast! / The scent opens your eyes.” “So kiss a little longer / Stay close a little longer / Pull tight a little longer / Longer with Big Red.” At Arkansas Governor’s School, a few of us developed a game in which someone would name a word—any word—and the rest of us would have to come up with a song that contained that word in its lyrics. I rarely missed. A college friend of mine once told me about a dream she had in which she walked into a concert hall to find me sitting at a cafeteria table as though it were a grand piano. A hush fell over the audience as I began drumming on the tabletop with my fingers. “Come On Eileen,” I sang.

Back then, in the din of a crowded party, when I didn’t know anybody and my friends hadn’t arrived yet, I liked to sit by myself singing in a corner, just loudly enough so that my voice blended into the background rustle of the conversations and no one else was quite able to hear me. I sang when I was walking to class, and when I was driving in traffic, and once, with a friend on a Spring Break trip to New York, in an elevator surrounded by complete strangers. I sang because it made me feel more alive—happier when I was happy, angrier when I was angry, sadder when I was sad. I sang because it seemed to join me to some rhythm I could sense flowing just beneath the surface of the world. I sang out of a mental tic that summoned a lyric up out of every sentence I heard, a melody up out of every lyric. I sang out of habit and need and egoism, and I sang because I was in love with the singers of the world, and I sang to feel like I was speaking to someone. I went on this way until my mid-twenties, when I, as Harold Brodkey once put it, “began at last to be like other people.”

I don’t know why I changed. All I can say for certain is that after I earned my graduate degree and moved back home, and my sense of time became governed by which book I was working on rather than which grade I was in, my desire to sing grew more and more sporadic. It still flared up occasionally when I was in the car and an old favorite surprised me on the radio, but this happened less frequently with every year, and after a while I ceased to expect it. The way I listened to music began to twist on me, becoming less theatrical, more interior. My ear for certain albums changed in ways I had not anticipated. A time came when I needed to be spoken to more than I needed to speak. And that was when I found Iris DeMent.

Ever since then, I have returned to her songs again and again when I wanted the comfort of hearing someone who was capable of transforming her sorrow into art. For though Iris is a country singer, with a country singer’s lilting inflections and a country singer’s lack of disguise, she has made her home in that fertile place where country meets the blues. Her music is music for mourning. There are times when no one can take your mourning away from you, but the great singers, like Iris, have the ability to lift it up and cradle it in their voices, and in that way make it complete.

Read more from Issue 58, our 10th Music Issue (Fall 2007).