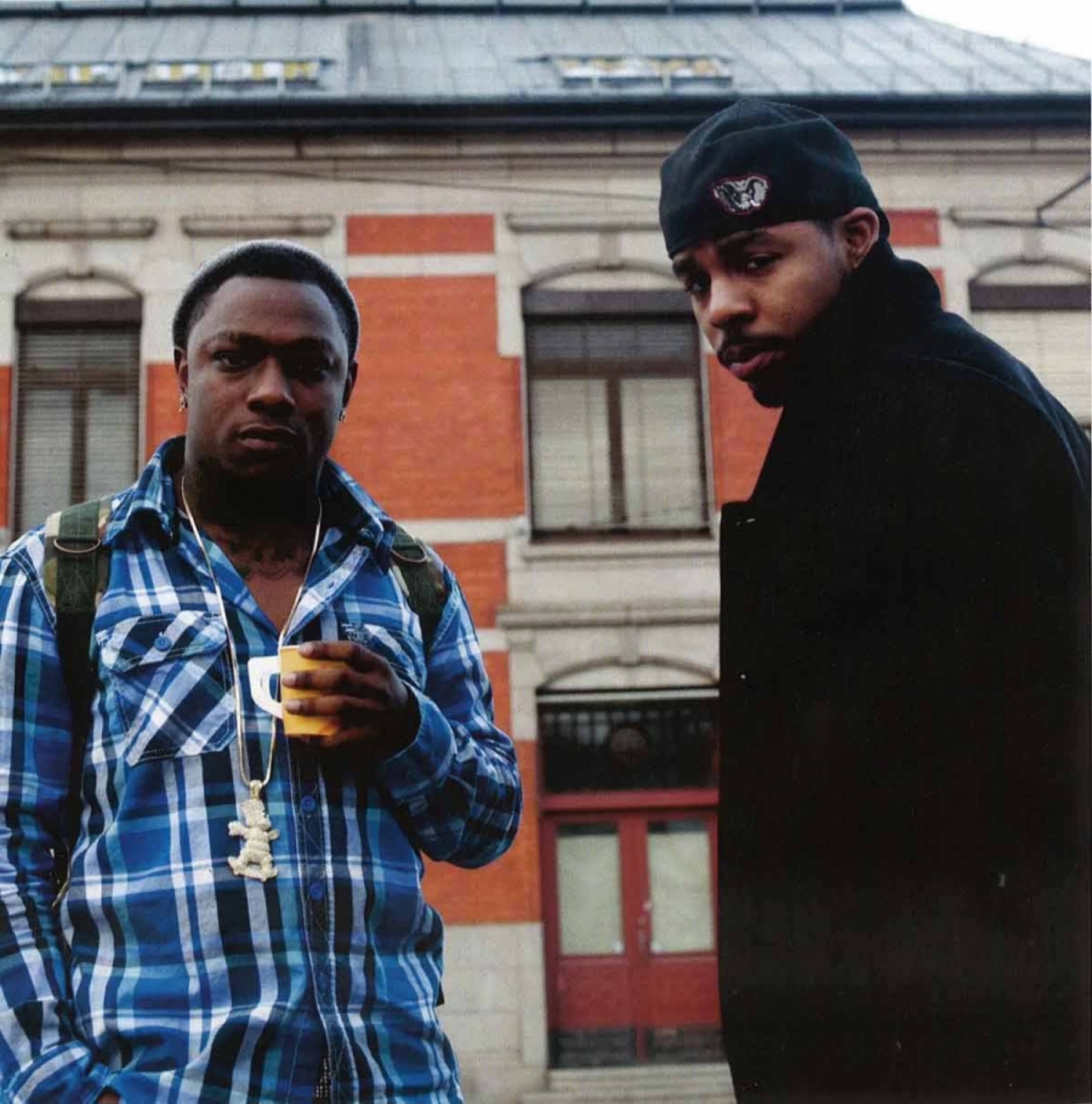

G-Side, Clova (left) & ST (2010). Photo by 30packpat

Not Your Typical Anything

By Jon Kirby

Until the late ’90s, Southern rap was an only child, caught in a custody battle between the indifferent parents of the East and West Coast movements. Once emancipated, rap franchises gained footing across the South, with strongholds in Houston, New Orleans, and Atlanta, the arguable epicenter. Southern rap was in high cotton, and the record sales, award-show statuettes, and tour schedules reflected the South’s growing market share. But with innovation came imitation; cookie-cutter acts diluted the talent pool, and with a few irresponsible handshakes, Atlanta became more Animal Farm than Motown, adopting the unscrupulous policies of the establishment it once defied. Sure, we’d overthrown dictators like Puff Daddy and 50 Cent, but only to replace them with “Pretty Boy Swag”?

“That is a conspiracy to me,” declares Codie G, one of the many staff visionaries at Huntsville’s premier label, Slow Motion Soundz. “Because if a great record comes across your table, and ‘Pretty Boy Swag’ comes across your table, and you choose, in your heart of hearts, to play this record over the dope record, then American music is fucked—rap music is systematically done.”

On record and off, Codie G is a dead ringer for Big Rube, the sagely orator who gave early Outkast albums their conceptual glue (Codie provides the slow-motion sermon featured on “Huntsville International”). Enabling the artists to focus solely on their art, Codie serves as a business-savvy conduit between the world and the entire Slow Motion Soundz roster, which includes sundry producers and groups, including the enigmatic duo G-Side, whose trajectory and destination are appropriate in a town nicknamed “Rocket City.”

“This could be a career move for you!” exclaims rapper ST from the driver’s sear of a luxury sedan. As we creep along the narrow streets of Athens, Alabama, G-Side’s collective birthplace, he and partner Clova (David Williams) swap perspectives on this aspect of their shared history.

“You know everybody in this city,” professes ST, born Stephen Harris. Clova adds: “Somebody would get robbed, you’d be like, ‘Ah man, that was Wesley and them—’ You know who did it! You be like, ‘Why they do that, man. . . . ’”

Here, thirty miles west of their adopted hometown of Huntsville, the feel-good ghetto tales are bisected by tragic ones—the overdoses, the shootouts at the T.G.I. Friday’s. Clova waves to his fifth grade teacher who sits on a nearby porch. In a way, this trip constitutes an illustrated guide to G-Side: a tale about beating the odds, turning negatives to positives, and not becoming a statistic. “You’re the first person to really come down here,” ST reinforces. ‘‘If this album blows up, you’d be like, ‘Yeah, I broke those dudes.’”

G-Side is a group that has been on the brink of underground eminence for the bulk of their career, and they’ve been discovered several times. Effortless to enjoy, difficult to compartmentalize, the most logical ways to describe them seem contradictions in terms. Outkast on steroids? On Quaaludes? Fair-trade gangsta rap? Their songs are evocative, empowering, and often autobiographical, fusing the good with the bad, and making responsible distinctions between the two. While applauded in the pages of the New York Times and the Village Voice, they’ve evaded mention from traditional rap rags like XXL or The Source. And though a web of Internet radio stations and podcasts keep the duo in heavy rotation, they’ve spent little time on actual radio airwaves outside of Northern Alabama.

Their ascent has not been typical, as G-Side is not your typical anything. The Slow Motion Soundz business model—web-heavy and grassroots—more closely resembles that of indie institutions like Merge Records than once-mighty rap dynasties like Jay-Z’s Roc-A-Fella. “I’d never heard about Arcade Fire until I read this article in Spin,” declares Codie G. “One hundred fifty-six thousand units in the first week? And they’re independent? Two sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden? That’s beautiful. That’s special for independent music, period.”

Most facets of the music industry have changed, and Codie G finds humor in the outdated model to which most rap acts still adhere. “It comes to a point where people say, ‘When are you going to blow up?’ What do you ask Arcade Fire? ‘When are you going to blow up?’”

ST and Clova met as teenagers at the Boys & Girls Club of Athens and began rapping together soon thereafter. While they honed their skills, committing hood narratives to cassette with a pair of hardwired karaoke machines, their future label, Slow Motion Soundz, was developing its own formula, auditioning an assortment of synthesizers and software, wrapping a gooseneck computer mic in panty hose to gather vocals. Having since upgraded to NASA-caliber equipment, the ethereal productions of flagship producers CP and Mali Bai—known jointly as The Block Beattaz—retain the same passion and exhibit the same hunger demonstrated on earlier, if more modest, Slow Motion efforts.

Although the lion’s share of their output remains in the family, a handful of compositions have fetched impressive coin from movie houses and recording artists alike. A British Beyoncé (Alesha Dixon) and a Midwestern Justin Timberlake (Mike Posner) have both utilized the lush instrumental for G-Side’s “Speed of Sound,” built bemusedly around the bridge to Enya’s “Orinoco Flow.” The more absurd the sample, the more attractive it becomes to producer CP, who has all but abandoned the funk graveyard in favor of the untapped realms of world and classical music. After that, his beats are usually double-stitched with natural and artificial drum sounds, primarily from the Roland 808, a primitive drum machine—considered the backbone of ’80s rap—stocked with a ubiquitous library of sounds ranging from digital tidal wave to space cicada to heavyset Atari sex. Although the Block Beattaz have seen respectable success doing things their way, they still encounter the occasional industry hardhead who tries to strong-arm them into modifying their sound. “You can’t go to Memphis and tell blues players, ‘That ain’t how the blues is supposed to be played,’” says Codie, as Howlin’ Wolf plays overhead. “In the end, whoever changed their sound, lost.”

G-Side’s recorded fare—Sumthin 2 Hate, Starshipz and Rocketz, and Huntsville International—are self-referential Alabama classics, each more remarkable than the last. They are each a testament to G-Side’s adaptability, recorded piecemeal in an array of dodgy basements, bedrooms, and lean-tos. “Our studios used to be the worst places on earth,’’ claims Codie. “You might go through this door and there’s the worst sexcapade imaginable, run next door and there’s a pit bull having babies, go to the next room and somebody’s asleep—they been asleep for two days.” The studio erupts in laugher. “I’ll say one thing,’’ concludes Codie, “the music was different.”

Their current headquarters in Huntsville consumes some thousand square feet in a business park among entities like Lockheed Martin and Teledyne Brown. Part honeycomb, part Q-bert board, the geometrically sound structure is home to a rotating cast of sitcom-grade characters—some rappers, some producers, some stragglers, but all integral to the chemistry within. As one conversation veers into religious territory, a wiry rapper named Junebug makes an impassioned declaration: “I believe in Jesus, God, Allah, Buddha, but all that might just be another word for alien niggas.” A few hours before a fleet of SUVs transports us to a cluster of strip clubs across town, the office hosts a baby shower for Clova and his girlfriend, who is weeks from delivering their first child. As the median age inches toward thirty, more toys litter the lobby, and more Tonka trucks are wrecked into the mini fridge.

With mouths to feed and dues to pay, most members of the team maintain conventional employment. Clova works at a barbershop that provides separate but unequal waiting areas for Alabama and Auburn fans (the Auburn side boasts no seating). Codie works for the government, and ST recently quit his job at a convenience store, the same one he shuttered midday a la Clerks in order to film the video for “Rising Sun.” The group’s numerous videos are produced in-house; all are pretty amazing, though some have achieved more notoriety than others. While marveling at the coed melee that accompanies the DB49 single “Club Pictures,” rapper Kristmas acknowledges with but a tinge of sympathy, “Yeah, some girl lost her scholarship over this one.”

Although the group had only traveled domestically upon the release of Huntsville International, the resulting momentum has taken G-Side as far as Norway to serve as ambassadors of the Huntsville sound. Their frequent flights have required some acclimation. “That first night in Oslo, we slept in our clothes—fully clothed—ready to go if something went down.” Clova shakes his head. “We watch too many movies, man.”

With everything to show and nothing to prove, all hands are on deck for The One. . .Cohesive, and the growing body of songs is astounding. “Mostly everything we do, we try and make it like it’s game time,” says ST. “No exhibitions, no warm-ups: Every time we get on the mic, we’re trying to make something that people are going to like.” As the duo pulls golden threads of metered rhyme out of their Palm Pilots, the products are burned to CD-R, and each spaceship in the Slow Motion armada is provided with more musical fuel. Although the team is in accord that Cohesive could be the fabled one, Clova makes a confident testimony to the dimension of G-Side’s enduring vision: “This isn’t going to be our best album,’’ he boasts. “We’ve got a lot more to come.”

To discover more from the archive, sign up for our weekly newsletter.