BOMBS FOR SALE

Two weeks in a Mississippi fireworks tent

By Nathan C. Martin

"Independence Day celebrations in Easton, Maryland, July 4th, 2009" by Peter Van Agtmael. Courtesy of Magnum Photos

I arrived for duty at the warehouse south of Jackson, Mississippi, on June 20. It was midnight, and a barbecue was winding down in the parking lot under floodlights that attracted bat-sized moths. A group of men played a game tossing metal washers into a bull’s-eye on the ground made of concentric squares of two-by-fours nailed to plywood. Karen, the boss and the only woman on the premises, directed me to sleep in the beige, corrugated-metal warehouse, and I stretched out on the painted concrete floor on a pad next to stacks of explosives, towering and shrine-like in their silence, their boxes branded with names like Black Mamba, Detonator, and The Passion of Canister Shells. What looked like colorful Tibetan prayer flags emblazoned with Black Cat logos hung from the ceiling joists and fluttered in the air-conditioning.

Karen emerged from her camper trailer shortly after dawn. She’s about five feet tall, with a stout frame, dark makeup, short brown hair, and a tough-mom demeanor I recognized from other female bosses I’d worked for on male-dominated job sites. She told me that the previous night, some of her guys had been making fun of my glaring white new sneakers. In a gesture I took as sympathetic, she pointed toward her sandals and admitted she couldn’t even wear closed-toe shoes—she had recently broken her foot. I asked if she’d be able to cope with the pain, and she told me about the premature C-section she had requested eleven years ago so she could heal in time to oversee fireworks after the birth of her son. Her doctor had ordered her to rest for six weeks, but less than a month later she and her team were loading a shipment at the warehouse. They were sweating in the heat when the woman next to her began to scream. Karen had not noticed blood seeping out of her unhealed incision, darkening her shirt and shorts. She rode to the emergency room in Hattiesburg and took off the remainder of the season. So no, she wasn’t worried about a little pain from her broken foot.

I met a guy named Paul in the parking lot. His eyes squinted behind a pair of glasses, and long blond whiskers curled down his sun-browned cheeks. I guessed he was in his forties. Paul was from Missouri, and he had come to the warehouse without an invitation—he’d tagged along with a friend—and had talked Karen into giving him a job in one of the tents. “You’re not a preppy guy, are you?” he asked me. “Check this out.” He produced a homemade firecracker, about the size of a roll of quarters and wrapped in red. He stuck it in my hand and said when it goes off, it feels like “this,” thumping two fingers into my chest. Paul said his dad had worked munitions for a mine while he was growing up. “Oklahoma City was nothing compared to the shit I detonated as a kid.”

Selling fireworks has traditionally been the province of carny types and college kids, though lately there’s been a change in this small Mississippi slice of the industry. I had driven up from New Orleans, where I live, to join a group of twenty-going-on-thirty-somethings from Lawrence, Kansas, led by my friend Cyrus, a half-white, half-Persian funk and soul enthusiast. Cyrus had worked ten fireworks seasons, starting when he was nineteen and a college sophomore. Fireworks jobs are filled by word of mouth, and Cyrus can trace the lineage of his involvement back to a Minnesota college student in the ’80s, a guy who went south for summer break to stay with his grandparents in Mississippi and discovered a fireworks warehouse nearby. Word eventually spread to Cyrus’s college in Lawrence, where the floor monitor in his dorm had gotten into the racket and put out a call to underclassmen for a tent mate. Cyrus answered the call. Between the couple grand he made that first season and his exposure to the region and culture, he was hooked—until a miserable, rainy New Year’s prompted him to quit. He graduated and stuck around Lawrence, and was working seventy hours a week at a bar and the local Goodwill when he ran into a guy he knew who had just come back from fireworks, flush with enough cash to make Cyrus seriously scrutinize his lifestyle and the feeble paychecks it generated. After a five-year hiatus, he went back to Mississippi, where he’s been working every season since summer 2008.

I had known Cyrus for six years, since the time I’d lived in Lawrence to attend grad school. He’d first caught my attention by devising a college radio marathon for which he and another DJ stayed on-air continuously for five days, never playing the same song twice, sleeping in shifts on the grubby floor of the station’s basement. I hung around with him much of that week, listening to his excellent sets that spanned geography and genre, from Brazilian funk to U.K. post-punk to American hip-hop. He described himself in all seriousness as a “jazz listener,” the way someone else might say he was a painter or lawyer or butterfly collector. Cyrus took great pride in his skills as a conversationalist, and he likened conversation’s highest form to jazz soloing—just as the improvising trumpeter moves forth through the song without a map, adept conversationalists say things they’ve never said before, rejecting stock anecdotes and small talk. He would tell me this at the station while covered in several days’ grime, bleary-eyed and pouring coffee from a pitcher he kept perched precariously atop a pile of vinyl records with dilapidated covers. When Cyrus asked me to do fireworks with him, I decided there was no one else with whom I’d rather spend two straight weeks in a tent.

The other young men from Lawrence were amicable enough. They came down in varying iterations for each Fourth of July and New Year’s season, and had arrived sometime after I’d gone to sleep. They arose late in the morning and began rummaging through their cars crammed with coolers, boom boxes, and books, looking for snacks and changes of socks, and a Frisbee they began to toss in the parking lot. For the most part, they held down jobs as waiters or teaching assistants in high schools, and most of them had various hustles that kept their bohemian lifestyles afloat. We boasted ten undergraduate degrees and two master’s degrees among the eight of us, but the brown bag of cash one takes home after doing fireworks was plenty of incentive to spend two weeks in a tent, particularly in the midst of the recession. The Kansans were all tall and decently fit, Cyrus the only one whose heritage contained a smidgen of dark skin. Their jolly nonchalance gave them the air of over-aged spring breakers on a camping trip.

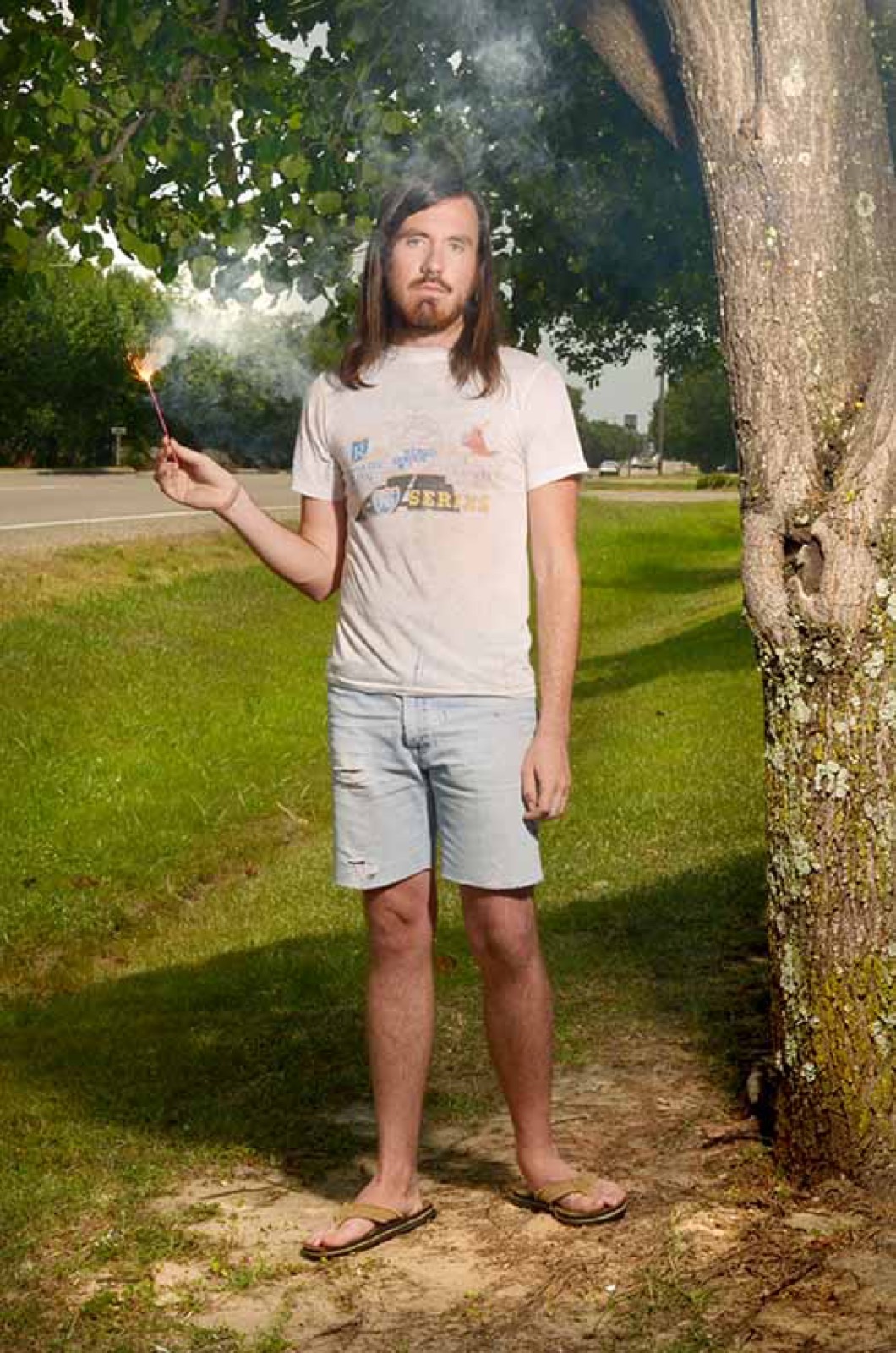

We rode out in a beat-up green van with no rear seats or windows. Behind us, three burly fireworks veterans—Brad, Justin, and Matt—sat in the cab of a Budget truck crammed with poles and tarps. Each had worked more than a dozen seasons and held commercial driver’s licenses; they were Karen’s immediate underlings and her most trusted associates. Brad didn’t have steady employment—he roamed the country doing odd jobs, having adventures, meeting people—and he looked like a guy you’d hire to guide a river rafting expedition, a strong-chinned outdoorsman with a barrel chest and flowing brown hair. Justin worked in some capacity on nuclear power reactors, but got time off every season to do fireworks. He wore wraparound shades, had short-cropped hair, and had a cross tattoo on his sternum. Cyrus told me of his oldest memory of Justin. At the end of his first season a decade prior, Cyrus collected his cash out of the back of a Budget truck parked at the Jackson warehouse. Karen gave him his brown bag, while Justin—at the time, about eighteen years old—sat behind her on a pile of boxes, waving farewell with one hand while using the other to keep a long shotgun propped across his lap.

Our first stop was Morton, forty miles east of Jackson, where we set up a tent for two of the Kansans, Wake and Alex. We thrust up the two-hundred-pound tarp on seventeen-foot center poles, four or five of us at a time manhandling them into position. We staked ropes into pre-pounded holes in the gas station parking lot, flopped out two dozen wooden tables riddled with staples, then moved on to Cyrus’s and my site, ten miles east in a town called Forest. Our location was on a patch of grass between a strip mall and a highway. A grocery store called Vowell’s Fresh Market piped Christian music into the parking lot. An overweight worker stretched from a chair to hang a banner advertising something called a “P’Zolo” on the awning of an adjacent Pizza Hut. We erected the tent, a clownish yellow-and-white-striped eyesore with a footprint of 40 by 90 feet. I walked a few laps around its interior, noting how little the shade dissuaded the heat. It was June 22 when Cyrus and I manned our tent. We arranged our tables in a circle to build a protected space for the stereo, coffee pot, and our three-man dome tent. We set out and priced our merchandise, from Cracklin’ Crawfish at $2.50 a pack to Zeus, which cost $100 for 24 mortar shots. And then we waited. One of us—usually both of us—would be in the tent at all times until July 5.

The group set up Paul’s tent a few miles down the road. Because he had come uninvited with his friend, Karen stuck Paul, alone, in the worst tent in the state. It was small and neighbored nothing that drew traffic. There were no nearby amenities, and it sat in six-inch grass that seethed with insects. Paul took his shitty tent in stride, though, during the four days he worked it. He sat shirtless on a canvas chair that he moved throughout the day to remain in the shadow from the equipment supply outpost that shared his gravel parking lot. He paid a local to cut the grass. He drank Busch beer and cheerfully thanked me whenever I checked in on him, telling me that a couple of ladies had been stopping by in the mornings to chat. Then, on the fifth day, he disappeared in the night with his friend. Paul’s friend had remained at the warehouse in Jackson with Karen and her crew. No one there liked him, and they let him know it. Video from the warehouse’s security camera showed Paul’s friend packing up his old Monte Carlo at about 10 P.M. and taking off. Karen called Cyrus the following morning to have him check on Paul, who was gone, along with $300 or so from the cash box and his garbage sack of personal effects, including his stockpile of homemade firecrackers and an antique .22-caliber pistol. Karen sent her fifteen-year-old son and his friend to fill in while she rounded up a couple of locals to hire. I now understood the perils of using carnies like Paul for your workforce, and why Karen and her associates were more than happy to employ overeducated strapping Midwesterners. They tended not to disappear during the night.

We had few customers during our first days in the tent. As the hours I spent sitting there with little to do and nowhere to go accumulated, my body began to complain. My torso and appendages just a few days prior had been tools I could use to accomplish tasks—like loading boxes of fireworks from semitrailers into Budget trucks—but now they were becoming burdensome entities, useless objects I had to position mindfully for long stretches of time in order to maintain some level of comfort. The only piece of furniture I had brought was a metal folding chair, which dug through my un-meaty ass and aggravated my spine’s pronounced crook. My body became something to protect—from the heat, for which I melted ice cubes from the cooler on my head, and from insects. You would think that over the course of two weeks, with all my spare time and human intelligence, I would have managed to devise some way of neutralizing the fire ants, whose “bites”—really, they plunge half their head into your flesh behind their mandibles—were painful and constant and showed up anywhere from my ankles to unnervingly near my scrotum. But like all insects, ants possess a frightening mindlessness. They neither scare nor become tired, won’t scatter at the wave of a hat or become docile after a chase. So we sprayed poison on some and accepted others, and strung our food on ropes as one might hang meat high in a tree while camping in bear country.

Cyrus devised a workout regimen to keep our bodies from wasting away: we did 120 sit-ups and push-ups a day, spread out in 20-rep sets. To this, he added an afternoon 35-minute run around the tent, which he timed by playing the same mixtape up until a certain song: “If You Believe Your God Is Dead (Try Mine)” by Swan Silvertones. I sipped from a small blue cup the rye whiskey my friend had recently brought me back from Tokyo while Cyrus chugged out his laps, sweat streaming down his shirtless torso and collecting in deep, vaguely obscene stains along the rim of his shorts. We did push-ups and sit-ups on cardboard mats, and I felt manly and somewhat militant, thinking of our regimen as something soldiers might do on base while waiting for deployment. As I stood on his toes to keep his feet down while he did sit-ups, I thought of how much Cyrus’s receding hairline, mustache, sideburns, square jaw, and broad, hairy chest made him look like an old-time bare-knuckled boxer. But I understood how passersby might notice instead that we were two mostly undressed men, one thrusting his face repeatedly toward the other’s crotch. I saw people gawking at us from pickup trucks as they left the Vowell’s parking lot. The first time the area’s night-shift police officer came to visit, he returned my greeting by looking to the side, slowly removing the coffee stirrer from his mouth, and asking, “Y’all done with yer sit-ups?”

Customers who remarked on the heat tended to do so in biblical terms. One large black man with a severe limp lumbered with difficulty around our tables, swatting at the gnats that had infested our tent toward the end of the first week. He stopped, shook his head, and exclaimed to no one in particular, “I’m sweating like a Hebrew slave!” Another day, a white soccer mom told me it was so hot the Devil was at Lowe’s buying an air conditioner. As I stared at her, unsure how to reply, her young daughter pointed at the tent where Cyrus and I slept and asked, “Mommy, what’s that?” Children asked this question every few days and it always elicited squirms of discomfort from their parents. I wanted to tell them to relax. Even if Cyrus and I had been lovers, it was far too hot to have sex. He and I alternated morning duties so one person would have the chance to sleep in, but whoever remained in the tent invariably spent their extra hour sweltering restlessly in what felt like a mouth. One morning while Cyrus was opening the stand for business, I dreamed I was naked and covered in oil, giving a beautiful woman an erotic piggyback ride. I awoke to realize that what I had felt was my sweat-slicked back rubbing against the plastic floor of the tent.

The practice of arriving uninvited in someone else’s town and erecting temporary, highly visible structures in order to coax the public into buying whimsical holiday merchandise is admittedly ominous and odd. I remember being in a dive bar in Chicago years ago, chatting up a couple of young men, when the bartender pulled me aside to warn me that “those are the boys selling Christmas trees in the lot down the street.” Thanks to the circus-like tents, people associate fireworks companies with traveling carnivals. And time and again, parents would sigh to me and lament that we had set up shop so far in advance of the Fourth of July. Their children recognized the tent from the road and knew what it meant, which translated into multiple visits for the families—I imagined some mother making elaborate detours down back roads through residential neighborhoods in order to avoid passing the tent with her child in the car. A large section of our customer base were parents who only spent grocery or gas money on things that literally burnt up in seconds because of their children’s insistence. Some mix of guilt, obligation, and desire to please compelled them to make the $30 or $40 sacrifice.

One memorable mother and child came in late one night, early in the season. The mother wore a tattered tracksuit and had a deep, uncovered five-inch gash just above her jawbone. She asked if we had anything for ten cents. Her son, who might have been ten years old, wandered behind the tables into the area of the tent off-limits to customers. When I tried to explain this to him and usher him out, he looked at me dumbly, not processing what I had said. I tried phrasing it differently, but the standoff continued, the child looking scared and confused, as if about to panic. Then his mother shouted, “Get over here!” That he understood, and he went to her. I sold them some bottle rockets at a discount.

It didn’t take long to learn that I should adopt an empathetic demeanor as I collected customers’ cash and stuffed their doodads into paper sacks. A normal cheerful checkout-clerk shtick would provoke glares and grumbling—better to shrug in a manner that expressed “we all do what we’ve got to do.” If I acted too happy while I took their money, my customers seemed to say with their eyes: “The least you can do is not grin in my face while you come into my town to sell me bullshit.”

I often thought of these grumpy parents in relation to the sheer joy an explosion of sound and colored light can instill in children and in adults whose spirits have not been crushed. There’s something wonderfully democratic in the faces of crowds watching a display light across the sky. The relaxed cheeks, upturned chins, and eyes that at once dilate and reflect at each blast suggest to me something profound, a common and intrinsic sense of awe and pleasure that unites us, if only for a few moments. Whenever a customer made a purchase that it seemed he or she couldn’t really afford, I comforted myself by thinking of the psychic salve of a fireworks spectacle.

As the days oozed by, Cyrus and I discussed the ways in which a fireworks salesman should comport himself. Not abusing the locals was one consideration, but another was not getting robbed. Shoplifters afflict every tent and can be deterred to only a certain extent, but our real worry was someone coming after the cash box. Karen or her cadre would come by occasionally to collect money, but we all spend most of the season sitting relatively defenseless on a pile of raw loot. Cyrus and I constructed a framework of guiding principles that informed our daily protocol so that we would not become targets. We used the day-drinking, Frisbee-tossing, DVD-watching, ironic t-shirt-wearing examples of Wake and Alex in the Morton tent as the counterpoint to our vigilant conduct. This boiled down to our taking part in four primary activities: reading, working out, conversing, and listening to exquisite and far-out jams, such as Esther Williams’s “Last Night Changed it All,” Sons of the Kingdom’s “Modernization,” and a mixtape of Latin American obscurities by Carlos Tropicaza. We kept our food rations sparse because of the heat: fruit and bread for breakfast, and “tent tacos”—avocado, lettuce, sliced bell pepper, and cheese wrapped in flour tortillas—for most other meals. We didn’t shower. We traversed the Vowell’s parking lot to use the restroom. The distinction between our activities and those of the Morton crew may have been ambiguous to the untrained eye—we were all just loitering around our tents—but Cyrus and I were sure there was an important difference. We made certain to approach fireworks as a job, and not an “adventure” that provides “many stories to tell, my friends,” as Wake described it to his Facebook followers in a caption to a photo of him holding a red-white-and-blue Miller High Life can in one hand and a huge bottle rocket in the other. We told ourselves that a potential robber would be warier of us than of Wake and Alex, less likely to enter our tent and case the joint. But really, we just had lots of time on our hands to talk about this sort of thing. Having your tent stuck up is bad luck as much as anything else.

On the night of July 3, after we had gone to sleep, Karen called Cyrus and told him to sit in the car with the headlights on and call 911 if anyone approached the tent. Wake and Alex had just been held up at gunpoint, and she was worried the assailants might come after us next. Movie-informed logic told me that heading for us in Forest would be the smart move for the robbers—every excitable small-town cop within radio range would be congregating in Morton, leaving vulnerable our cash-flush tent. Unsurprisingly, no criminal masterminds appeared, and instead we sat in my car with my baseball bat for a couple of hours until Karen showed up with her husband, a bulbous and dim-witted man whose most memorable characteristic was the extraordinarily large size of his t-shirts. Their sleeves extended well past his elbows, and as he waddled around our parking lot gazing aimlessly into the darkness, he looked like a blob with tiny stubs for limbs, one of which clutched a tremendous silver handgun.

The perpetrators had been kids—17, 18, and 19 years old. The eldest, also the gunman, had a record. They got away with several thousand dollars. The next night, a police officer who was keeping watch at our tent told me there had lately been a rash of home invasions in Morton targeting Latino immigrants, and he figured this incident was somehow connected—after all, we were sort of immigrants ourselves. Wake later told me that the whole thing had seemed a bit farcical, the boy with the gun not quite sure what to do, relying on Wake and Alex to go through the motions. Wake had sensed through the masks of the gunman’s younger friends that they had been wishing they were anywhere else in the world. After taking Wake and Alex’s statements, the police chief told them they were going to go “kick some doors in.” They made the arrests within a few days and found a gun that matched the description Wake and Alex had given.

Cyrus had kept an unloaded 12-gauge shotgun displayed in his tent for a few previous seasons, with three shells each in his and his tent mate’s pockets. I figured he was paranoid, but during the long exchange of stories that filled our weeks in Forest, he told me about a man in Vicksburg who had stalked drunkenly around the gas station next to his tent, waving a handgun until the clerk locked the doors and announced on the loudspeaker she had called the cops. Then he told me about working a tent in Canton, where, one season, two groups of teenagers converged on the gas station close by and began to fight. Cyrus saw one boy shoot another in the torso, and shoot the boy once more while he was on the ground. The kids scattered, the gunman running directly toward the fireworks tent before veering down the street. Cyrus had ducked behind some bushes, but he could see the dead body until someone came and covered it with a tarp.

Even if Wake and Alex’s slacker demeanor didn’t directly correlate with their getting robbed, they personified a cultural phenomenon that’s a major reason one can find college-educated grown men selling fireworks from roadside tents. The way in which American society has granted implicit permission for its young people to remain adolescents well into their twenties has been much discussed. With no pressure to marry, buy a home, or start a career, a generation has busied itself with pursuits that are, if not frivolous, at least staunchly transitory. Cyrus earns most of his income playing DJ gigs and selling vinyl records on eBay. Wake traffics in vintage clothing he sells from an antique mall booth. Neither plans to start a real business based on these pursuits—Cyrus figures he’ll work as a high school teacher once he burns out on DJing—just as countless droves of the country’s young “creative class” are really dabblers or aspirants, jumping from internships to freelance gigs while working in bars, vaguely assuming that one of these days it will be time to grow up. In this milieu, selling fireworks does not seem radically beneath what many college-educated members of our workforce are doing anyway—the optimist might say it’s an innovative means by which one can navigate the New Economy. If you get a gun shoved in your face, all the better story for your friends.

But what the hell was I doing here? I have a four-day-a-week job writing propaganda for a Jesuit university with salary and benefits—a job that let me take a leave of absence to sell fireworks—and I have money in the bank. I wear a tie to work (and a cardigan with lapels when it’s cool enough), and I eat sushi most days for lunch. I haven’t had a weird job since I was educated enough to avoid one—though my experience as a highway construction traffic controller and oil-field roustabout qualify me for all sorts of low-skilled unprofessional labor. My three years in New Orleans made me far more at home in the South than any of the Kansans, but while they appeared to be obvious outsiders, I was a tourist of a different type. My foray into the world of post-collegiate fireworks selling was a vacation from my relatively responsible day-to-day. My favorite thing about the experience was the break from modern life it afforded—or imposed. The one time I tried to check my e-mail at the Forest Public Library, I sat down at a spotless blond-wood table in the impeccably clean, quiet main room of the recently renovated building, opened my laptop, and a swarm of ants poured out. I closed the machine, kept as composed as possible while squashing the ants, and swept their corpses onto the carpet. After retreating to our site and settling in to stew in my own filth with a book, I was seized by an almost giddy sense of harmony and belonging. I was relieved to be back in the tent.

The Fourth of July brought the first rain in weeks, which made worse what had already been a slow season. A family badgered Cyrus over the price of an expensive purchase, the patriarch seemingly intent on asserting his manliness and self-assumed haggling savvy. Cyrus relented just to get rid of them, only to find they had locked their keys in their truck and had to stand in the corner of the tent for an hour to wait for a spare. I listened to an explosives nut in coveralls with a pumpkin-sized head who looked uncannily like David Foster Wallace tell stories of the time he blew up himself and his friends. “It looked like someone had splashed a gallon of red paint all over the walls,” he told me. “That was our blood.” I sold a bundle of Roman candles to a blind man who said he liked to shoot the ones that emit different colors so he could feel their frequencies change in his hand. I spent a long time talking to a Katrina refugee who had yet to make it back to New Orleans. His tendency to punctuate his sentences with “Ya heard me?” gave me the first pangs of homesickness I’d felt on the trip.

We spent July 5 boxing up our leftover stock, and at 9 P.M., a convoy of Budget trucks driven by Karen and her underlings barreled into the parking lot and backed up in a row to our tent, a dull “boom” issuing from each truck’s mostly empty cargo hold as it popped up the curb onto the grass. Wake and Alex followed in their car, and a dozen or so people from the warehouse piled out of the trucks wearing cowboy hats and Indian headdresses as part of an annual effort at joviality to make tear-down more bearable. We worked with invigorated swiftness, moving intuitively around each other as we picked apart the tent bit by bit. From there, Cyrus and I joined the caravan in my car—the first time in two weeks we’d been together outside the tent—and drove it down the highway through miles of blackened pine forest. We spent the night careening through the Mississippi hinterlands, breaking down tents and dropping loads back at the Jackson warehouse. At dawn, I found myself riding east, looking into a pink sunrise pierced by two ringed planets through the panoramic windshield of a thirty-foot truck. The work continued into the next day without rest, the tentacles of the central Mississippi fireworks industry retracting to await the winter season. In the afternoon I sat with Wake and Alex on a cement pad in front of the warehouse, drinking Gatorade, while Cyrus and two other Kansans haggled with Karen in her trailer about how much we would all be paid. Near sundown on July 6, I got my promised brown bag of cash. After 39 hours without sleep, I headed back to New Orleans, gripping the steering wheel and singing loudly to keep myself awake. A deep, peaceful sense of bliss enveloped me shortly after I crossed into Louisiana, and instead of worrying about whether I was slightly swerving, my mind began to loll and relax. I opened my eyes in panic as my right tires crossed the rumble strips and I began to scan the horizon for the lights of the next truck stop.