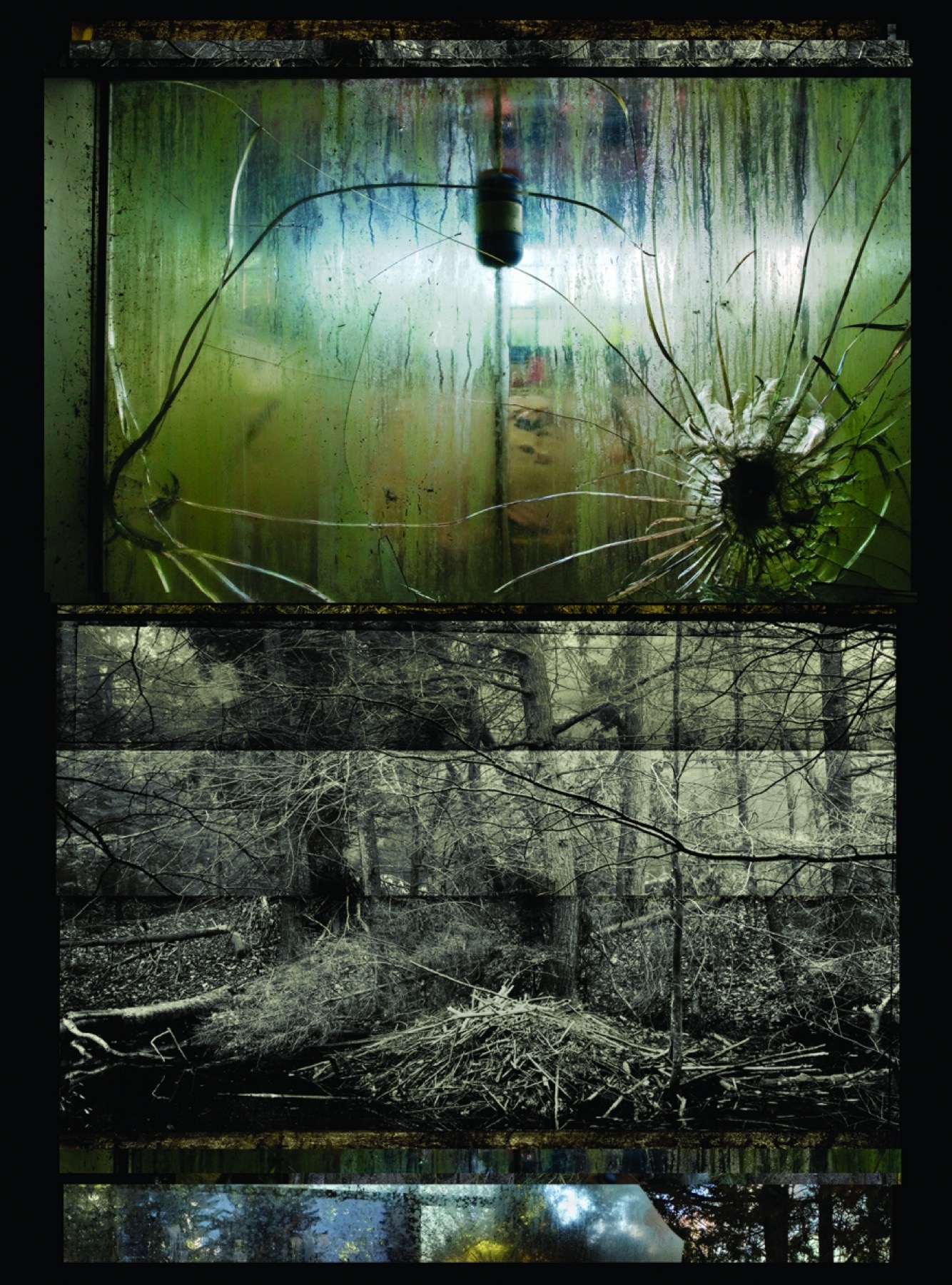

"Underwater Window" by Tom Young, from "Timeline: Learning to See with My Eyes Closed" (GFT books, 2012)

The Bootlegger and the Baby

By Beth Ann Fennelly

Dixie Clay began to creep forward, staying low. The smell of smoke got stronger as she snuck around the side of the house. When she pulled even with the front gallery, she could see an unfamiliar roan horse tied to her postbox. She leaned her head from behind a clump of holly bushes, but the gallery was shrouded by pines and all she could see was a muddy cowboy boot propped on the rail. It was wagging with the music, which was coming from her mandolin.

The tune changed, the voice deep and unafraid:

Trouble, trouble, I’ve had it all my days.

Trouble, trouble, I’ve had it all my days.

It seems that trouble’s gonna follow me to

my grave.

If this was a lawman, it was the damnedest damn lawman she’d ever seen. But it wasn’t a customer either—a customer would know better. The boot wagged on until the last note died.

“Well,” asked the voice, “how’d you like that?”

Dixie Clay started. He’s spotted me, she thought. But then there was another sound: a high sliding three-note wail. She knew it for what it was. A baby. What kind of drunk brings a baby to a bootlegger’s? And why was it crying? She sprang from the bushes and aimed her rifle at the boot.

“Hands up!” she yelled. “I got my gun and I’ll shoot you dead.” She couldn’t see much as she half ran, half slid down the gulley, just knees and then a torso, arms held in the air, the mandolin between them. She scrambled up the steps, sighting down the rifle the whole time. When she reached the top, she saw the rest of him: a big man, his long right leg bent, boot on the rail, his left angled open, ankle on knee, and, in the opening, a bundle. A bundle with a spastic arm: a bundle of baby. The man’s chair was balanced on its hind legs, and as he appraised Dixie Clay he let the front legs bump down. He started to lower the instrument so she yelled, “I SAID HANDS UP.”

He straightened his arms again, a corner of his mouth curving with a quick siphoning dimple, which disappeared as she trained the gun on his heart.

“What are you doing here?”

He tilted his head beneath his brown hat as if sizing her up. “I came to bring you a baby.”

“A baby?”

“Yeah.”

“You came here to bring me a baby?”

“Yeah. I came here to bring you a baby. This here baby. A real American-style baby. Bona fide A-one cowboy, too. Likes the open road, Nehi soda. Loves the blues.” The baby gave another cry and the man shrugged. “Well, usually he does. That was Bessie Smith. Your husband play?”

She said nothing, trying to gauge what type of crazy she was up against. She glanced around to make sure he was alone. To the side of the gallery, where she’d stuck a few measly rosebushes that had since drowned, was a collage of broken glass. She’d left a Dr. Pepper bottle on the wooden crate, saving it for the refund. Why would he smash her bottle?

“You want a baby?”

She couldn’t figure out his angle. He didn’t appear to have a weapon. He had a strange way of saying his Rs. He wasn’t from around here. She glanced behind her: no one. “You’re . . . fixing to give your baby away?”

“Not my baby,” he said. “His mama’s dead. Daddy dead. Baby shoulda been dead, too, but I found him and for some fool reason decided to carry him around till I could nab him another mama. Can I lower my mandolin now?”

“You mean my mandolin,” said Dixie Clay.

He grinned and lowered his arms and set the instrument gently beside his boot.

She kept the gun trained. He slid a ring from his left hand and set it down beside the mandolin—no, not a ring, the bottle neck of the Dr. Pepper, which he’d been using as a slide. But who wears a broken bottle with a baby in his lap? The man leaned forward to lift a cigar from the porch rail, gave it three quick bellows to bring it back to life. He turned it to verify that its end was aglow. Satisfied, he took a longer puff and replaced it on the rail. Then he blew out the smoke in a slow stream, his dark brown eyes looking up at Dixie Clay.

“Well?” He lifted the bundle from between his knees and turned it to face her in the lingering smoke. “You want this baby?”

She studied it as it dangled. Hard to tell girl or boy. It was still fussing, kicking its legs a bit. It was dirty. Where its diaper cloth sagged, its belly was whiter than the rest of its torso. The man’s huge hands were dirty, too, fingernails rimmed brown, covering the baby’s rib cage. The baby kicked harder, and the diaper slid an inch down its hips. The man turned the baby around and set it back in the crook of his knee and began to tug the cloth higher. “I had him in some clean duds,” he said, “but there was an accident.” To the baby he added, under his breath, “Now don’t you go wetting on me again.”

Dixie Clay studied the man now, slab-shouldered and rough-looking, muddy dungarees plastered halfway up his legs, red henley shirt open at the collar, in need of a shave. And a haircut. Brown shag poked from his misshapen leather hat. He looked up then and caught her looking, and she lifted the gun, which had sagged a few inches.

“Listen,” he sighed. “You don’t want this baby, fine. Fine. I’ll find someplace better. But I gotta find it quick. The woman at the store said start with you.”

“Woman at the store? What woman at the store?”

“Big woman. Maybe fifty. Gray hair. Lots of rings.”

“Amity.”

“Whoever. She said you’re in the market for a baby.”

Dixie Clay looked and looked but didn’t say a word.

The baby gave another protest, not quite a cry, but not quite not a cry.

“Aw, hell,” the man said, and lifted the baby from beneath with one hand, reaching for his cigar with the other. “Gotta be an orphanage in Leland, or Indianola.” He stood.

“Give it,” she said, quick.

“It ain’t an it,” he said, drawing up to his full height. “He’s a boy.” He addressed the baby now: “Ain’t you, Junior?”

“Give it.” She held out one hand. “Give it here.”

He tilted his head at her again. “You want him, you put your gun down and come get him.”

She did. She leaned the gun on the rail and crossed the gallery to where he was dangling the baby toward her. She slid a hand behind his back and another beneath his diaper and lifted him out of the man’s arms. The cloth felt damp and must have been chilly. But the baby felt solid, good and solid. She guessed him about six months. He didn’t have that newborn tremory head. He looked like he might sit up okay, secured by her afghan, say. She brought him to her chest and patted his back a few times and he slowed his fussing. Then she wanted to see his face so she lowered his head to the crook of her elbow. He had a swirl of downy dark hair. His eyes were closed beneath the faintest ridge of eyebrows. His face was dusty except where tears had cleared a path. He opened his eyes and suddenly she was being pulled into them, blue-gray eddies that held her fast. She closed her own eyes to break the spell.

Her voice was breathy when it came. “What’s his name?”

“Don’t know. Don’t know he got a name. I guess it’s up to you to choose him one.”

She looked up then and saw he was standing close, looking down at her and the baby. She stepped back, toward the gun, and folded the baby into her chest. “How do I know you’re not gonna come back for him?”

“Because you’ll shoot me dead if I try?”

She allowed herself a little smile. “Yeah,” she said. “Because I’ll shoot you dead if you try.”

It was his turn to smile now, and she saw the quick flick of dimples through his unshaven cheeks. “Well,” he said. “Let me give you Junior’s gear.” He walked down the steps and crossed to the horse. He flipped open the saddlebag and pulled several cans and packages into his arms and crossed back to the gallery and stacked them beside

her door.

“Okay then. I guess I’ll push off.” He touched two fingers to his hat brim, then inspected them and held them up to show smudges from the wet leather. But Dixie Clay was already turning away. She was patting the baby, walking inside, crooning him

low words.

Not till the next morning, when she drifted onto the rain-loud gallery with the dreaming baby in her arms, would she spot against the rail her forgotten gun. And the cowboy’s cigar, also forgotten, a half-moon singed into the rail where he’d left it smoldering when he rode away.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.