The Dead Give Him Stories

By William Giraldi

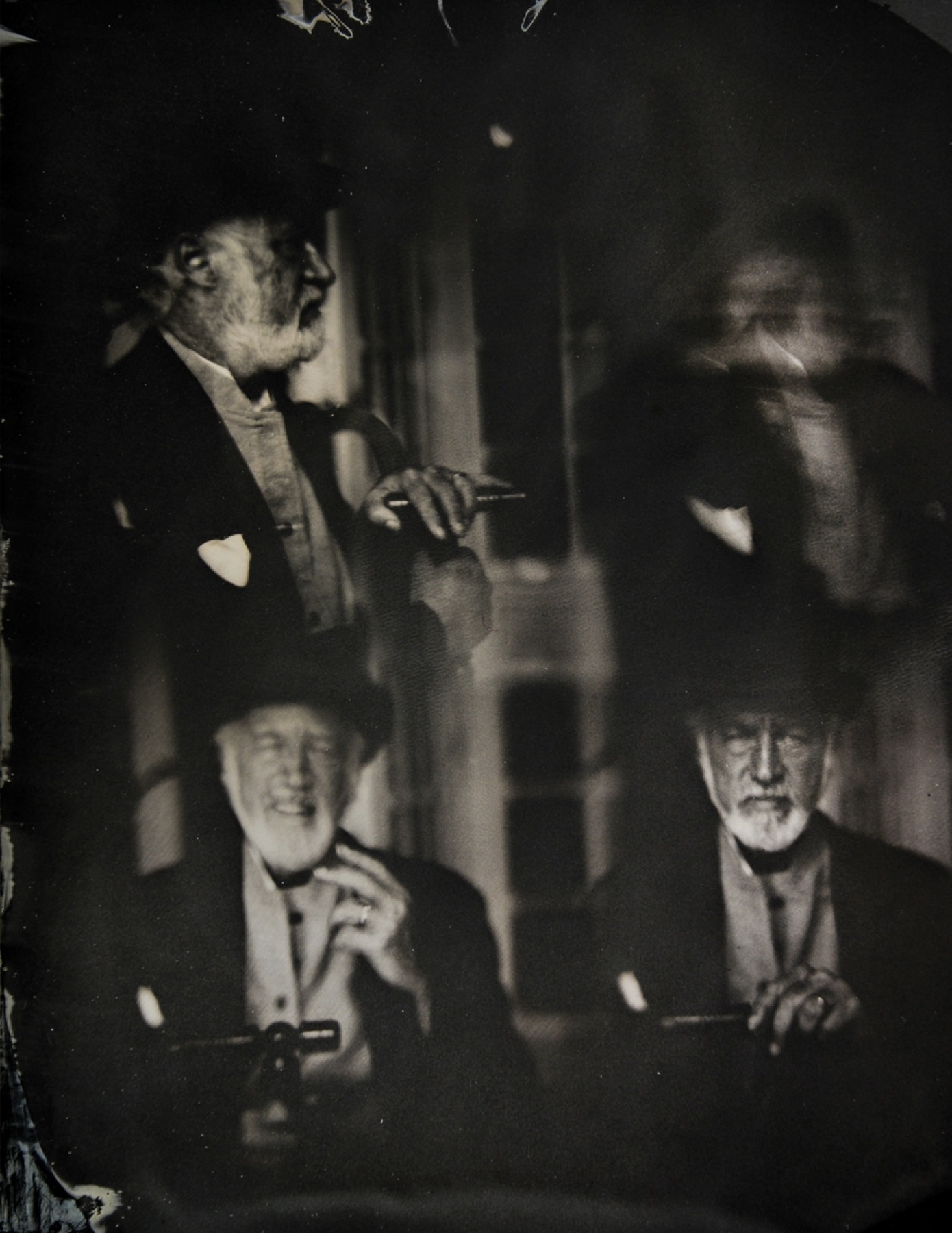

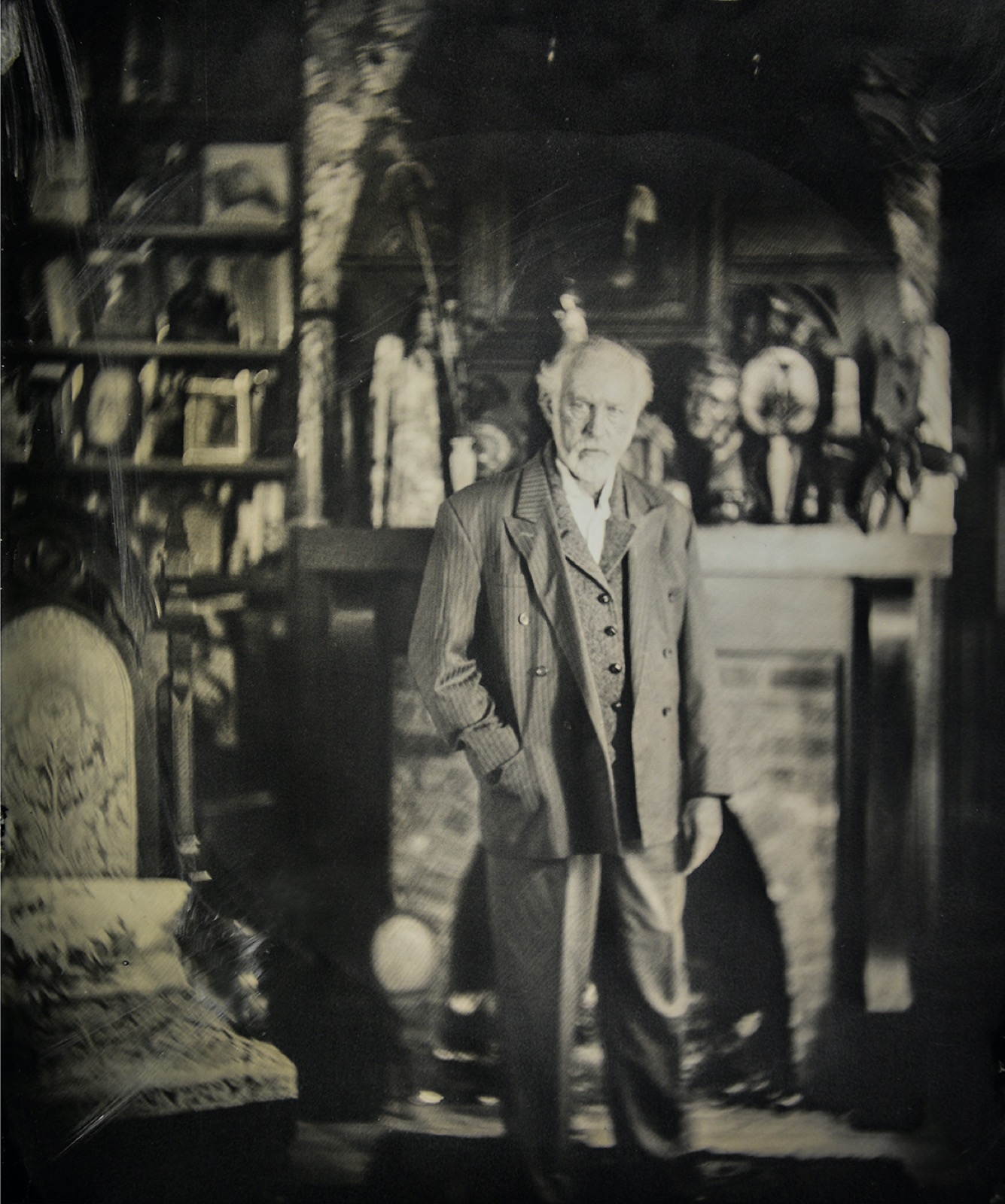

Ambrotypes by Harry Taylor

Allan Gurganus lives alongside the giving dead. The graveyard behind the Presbyterian church in his North Carolina village is twenty years older than the founding of our nation and Gurganus gazes at it daily from his desk. Fussily groomed and segmented by high hedgerows and three-foot stone and red brick walls, this sun-washed terminus contains some of the original colonists, several of whom were buried beneath the church itself to prevent enterprising Indians from digging them up. Colonists erected stone walls around clusters of graves to keep clumsy cows from tipping over headstones.

The Declaration signer William Hooper, who once lived next door, lies now along the low wall partitioning this acre of rest from Gurganus’s property. Hooper hailed from a neighboring county, and sometime during the last hundred and fifty years, the story has it, that county’s folks grew jealous of this cemetery for keeping their hero. They sent a shifty contingent to retrieve the body, but when they wedged open the casket all they discovered was a brass button. Gurganus loves that detail: the lone brass button atop the ashes of the once great man William Hooper.

And that’s what the dead of this place give to one of America’s preeminent novelists, our prime conductor of electric sentences, author of the incomparable behemoth Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, the showstopping Plays Well With Others, the profoundly humane and far-reaching short fiction in White People and The Practical Heart, and the just-released Local Souls, a stupendous collection of three linked novellas and his first new book in twelve years—these dead give him stories.

“Sometimes when I’m between chapters I come here and choose a name off a gravestone and imagine the character that would go under it, especially somebody who was very promising but died young. There’s something wonderful about that. I love it here. I feel very relaxed here. I grew up in a house that overlooked a cemetery. It was the place where I smoked my first cigarette, where I felt up my first boy, my first girl. They’re preserves of peace for me.”

Like any respectable boneyard, this one is haunted. The ghoul in residence? Dr. Strudwick, whose son, Shepperd Strudwick, played Elizabeth Taylor’s high-society father in A Place in the Sun. Gurganus tells it this way:

“Dr. Strudwick served on the vestry of the graveside church and took a great interest in the building and grounds. A friend and neighbor played the organ there for years. She always practiced on Friday nights. The organ faced the church’s rear wall but a mirror made it possible for her to time music to entrances, processional exits. Soon as her music started on Fridays, the ghost of Dr. Strudwick, wearing his trench coat and fedora, appeared seated in the back row. Responding to the anthems, he gently nodded, never critical. As soon as the organist recognized him, her panic lessened. She even came, over time, to count on him, a surrogate audience. When asked if she were not scared having a spirit as audience, she answered, Oh, that’s not such a ghost. That’s Dr. Strudwick. Local souls are forgiven a lot.”

For three over-warm days in late May, Gurganus welcomed me to his home to hold forth on his life and art, and on the imminent publication of Local Souls, about the invented town of Falls, North Carolina, population 6,803. An ordinary place of extraordinary people, Falls appears in nearly all of Gurganus’s fiction—“an inexhaustible resource,” he calls it, a town he knows with such kissing intimacy he can amble in it block by block and tell you how many cracks the sidewalks have. An artist since youth, a beholder incapable of not creating, he drew the detailed map of Falls that appears inside the book. What one first notices about the sixty-six-year-old writer is threefold: his polymathic erudition, his immense generosity (what other major American novelist would have not only retrieved my Bostonian self from the Raleigh-Durham airport but also greeted me inside bearing a pink sign that said “Welcome South, Billy”?), and his unstanchable need for storytelling. I had never met Gurganus before, except on his sublime pages. Still handsome, he seemed the genial curator of a skinny boy once far better looking. His voice contains the subtle, charming traces of Carolina and is quick to take on parts, to ape manifold accents during such charged storytelling.

Here from Gurganus’s wrap-around porch in the welcome shade of holly and spruce, amidst a racket of cardinals, jays, and mockingbirds, ancient stories are everywhere in reach. The man who built the colonial house right next door, who owned the ample land Gurganus now lives on? He was General Francis Nash (1742–1777), George Washington’s beloved prodigy battler, preternaturally attractive and charismatic, a dashing figure who could have made Lafayette himself feel substandard (the city of Nashville is named for him). At thirty-five years old he was mauled by a British cannonball at the Battle of Germantown, and although Washington’s own doctor tried to save him, Nash bled straight into afterlife and legend. The only time Washington ever leaked emotion in a public speech was during his oration over the young bloodless body of Francis Nash.

And the bronze bell in the tower of the original county courthouse, just around the corner from Gurganus’s home? This Southern bell, like every Southern belle, has a story to share. It was a present from King George to Lord Hillsborough, the aristocrat in charge of the English colonies. Twice this bell was removed from the tower: first when Cornwallis and his British goons stomped through, and again when Sherman was en route to scorch his merry way from Atlanta to Savannah. The townspeople feared the enemy generals would melt down the bell for bullets and, both times, suspended it in the river beneath the bridge. That’s another detail Gurganus finds irresistible: this goliath bell in the water beneath the bridge, the gargantuan, clandestine effort required to get it there and back. For three full days our separate streams of conversation pooled into a single inexorable river of expert open-talk.

“The greatest luck a writer can have is to be born in the American South. You grow up in a little Southern town and the stories preexist you. You memorize them till they seem to know you. The time grandfather got chased over the bridge by a scorpion. The day the pig fell down the well. The annual drama of named hurricanes. Burying all the silver and losing the map, endless people digging, trying to find the damn stuff. Naturally you add elements of your own biography to these stories. That makes for a new kind of catechism creating a new kind of literature. It’s the best training in the world both as storyteller and rememberer. And, like ocean waves, those stories keep coming, every day. Every time you read the newspaper there’s enough material to write War and Peace six times over.”

Some of the tales here are less ancient. Several years ago a crashing ruckus in his foyer jolted him awake at midnight. A meth-headed hooligan had entered his home in search of a soft-enough couch and in the dark he mistook a life-size bust for a man. Gurganus discovered this poor soul wrestling with an inanimate object on the floor. He said, “Who are you and what do you want?” and, incredibly, in a voice of boyish resignation, the intruder stated his first and last names. The cops apprehended him in a nearby yard: he was on a cell phone with his mother, pleading for a ride home.

Gurganus associates storytelling with “a farmer’s schedule and mentality,” a kind of planning for future crops, an at-bottom optimistic effort that helps us endure the frequent droughts of living. Storytelling was, remember, the first entertainment and our earliest font of information, an around-the-fire manna for those wide-eyed Paleolithic persons who became us. Gurganus’s storytelling sensibility clutches onto the collective consciousness, the tentacled imaginative faculty, that makes literature possible, that allows stories to take root and bloom beyond their place and time. Over my days with him, stories kept returning, renewed, improved. Among the myriad themes of Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, storytelling itself emerges as the most prominent: for more than seven hundred ecstatic pages Lucy Marsden is, as she says, “positively febrile with a storytelling mission,” with a “highly coloristic if rusticated narrative energy” and “propulsive inventiveness.” And the aim of that mission, that invention? “The best storytellers on earth, child, they’ve all stayed semi-furious defending something, expecting something—expecting something better.”

Gurganus was born and reared on stories not far from here, ninety minutes by car, in Rocky Mount, North Carolina (his family of merchants and farmers has been in the state since the seventeenth century). Rocky Mount was sixty percent black, and he had three brothers and twenty-six first cousins growing up. Twenty-six. That environment endowed him with an inclusive, elastic, impervious sense of community, of communal and social responsibility that stays with him still. He attended stellar public schools and received busloads of attention for his art (he held his first one-man show at age twelve and sold more than half the pictures). Dylan Thomas and Virginia Woolf were on the reading list already in seventh grade. “I had all these brilliant lesbians and brilliant single women who could have been running multinational corporations and instead were teaching me subjunctives.”

Like the man himself—and rather like Brando circa Streetcar (Gurganus is an American movie enthusiast, a freshet of reference and allusion)—Gurganus’s work is impossible to turn away from: the dulcet prose of a master craftsman; the gravitational pull of dramatic and meticulously measured storytelling; the tremendous affection and abiding empathy for his characters; the dialogue loyal to the nuanced pitch and rhythms of American speech (never as simple as it seems); the tender, precise sense of place to rival Faulkner’s famed county, Anderson’s Ohio burg, and Cheever’s Shady Hill; and, perhaps most remarkable, the easeful alloy of hilarity and heartwreck.

In a graduation address called “We Are Fossils From the Future”—delivered in May to Duke University’s first MFA class in documentary studies—Gurganus wrote, “Telling the story of the world means speaking the language of both elation and daily suffering.” He packs his storytelling with as much life, as much living, as possible. It’s an uncommon writer who can simultaneously don the masks of both Sophocles and Aristophanes, who can croon of our existence in all its multihued entirety, but Gurganus has been in possession of those outstanding abilities from moment one.

When Confederate Widow was published in 1989 it was difficult to remember a more capacious, more arresting American debut. The Anna Karenina–size life story of ninety-nine-year-old Lucy Marsden is a Whitmanian anthem of such dynamism, such linguistic bravado and historical sweep, it makes most other novels look downright malnourished. (It earned the Sue Kauffman Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, enjoyed an eight-month sojourn on the New York Times bestseller list, and was adapted for both television and Broadway.) Eight years later he published the virtuosic Plays Well With Others, about three friends in Manhattan during the hell-sent scourge of AIDS. The novel dazzles foremost with its acrobatic verbiage—Gurganus’s prolix delights are antidote to much of today’s costive prose so pleased to make us sleepy. At one point our endearing narrator, Hartley Mims, a writer originally from Falls, declares: “With us, it was reverse Bauhaus. Less Is More? Less ain’t, girlfriend. Mo’ is!—And Curly. And Larry, too.” The novel dazzles also with its deft oscillation between the direst pathos (beloveds emaciated, erased by plague) and a spirit-saving comedy (Hartley has a paper-bag malfunction on the subway and suddenly thirty rubber dildos are bouncing around the car).

The stories and novellas in White People (1991) and The Practical Heart (2001) flaunted Gurganus’s mastery of the short form—he was John Cheever’s star pupil at Iowa in the 1970s—and also his ventriloquist’s capacity for the embodiment of diverse characters: a melancholy Toledo woman who survived an uprising in Africa; a middle-aged artist who goes batty trying to judge a national art competition; an unstrung widow who finds an angel crash-landed in her backyard; a young boy overcome with sympathy and devotion for his cuckolded, unhandsome father.

And now Local Souls, novellas crafted of kinetic sentences, a bracing compassion for the citizens of Falls—citizens aptly self-titled the Fallen, with a nod to Milton—and a Proustian attention to the minutiae of lives that go from composed to chaotic. The book is an astounding testament to Gurganus’s narrative vibrancy, faultless plotting, and Everyman/mythic vision. In “Fear Not,” Falls is quietly scandalized by the taboo reunion of Susan and the now-adult son she gave up as a teen; in “Saints Have Mothers”—the stunning centerpiece of the collection—Jean suffers a fanged grief and near madness when her morally precocious daughter goes missing during an African trek and Falls makes the girl into a martyr; and in “Decoy,” the Fallen regard their charming doctor with the reverence and wonderment reserved for face-painted shamans, until the River Lithium promises to swallow half the town. Why tell the severest tales? In his Duke speech, Gurganus offered this: “I am not ambitious. I only want to tell the story of consciousness in the world.” And that story of our consciousness contains as much yin as yang.

Here on Gurganus’s immense wrap-around porch with the Moorish arches and antique chairs, with the busts and sculptures on column pedestals and the many potted plants breathing beside us, in view of the hyperactive vegetation flanking the front walkway, tall lilies about to burst into trumpet-sized yellow bloom, and across the road a twelve-story white oak with so much personality it looks prepared to speak—here on this porch we will engage in three days of old-time Southern storytelling and much talk of literature. The most comfortable, revered rocker became “my chair.” Plates of food kept appearing.

“Look, there’s a bluebird trying to make a nest out of my pillow’s stuffing, in the white chair. I’ve often had wrens claim the mailbox. They’re so curious they sometimes dart into the house or even my car. I somehow dread being in small spaces with flying creatures. Must be some unpleasant caveman memory.”

We’re in the South. Tell me about Faulkner.

“I go back to Faulkner with awe and reverence. His gigantic project speaks to me. Because of Faulkner I drink very little. One has few enough brain cells as it is. Poor Fitzgerald, too. Rereading Tender Is the Night I can see where the binges started and stopped. But Faulkner is the key to Southern literature’s being so respected by the international community and so imitated. Garcia Marquez’s output is a direct tribute to Faulkner’s fearless mythic imagination. Unlike Northern or Midwestern writers, Faulkner could trace suffering to loss of a war on one’s own soil. You study those photos of Richmond and Atlanta in 1865 and you’re looking at Dresden. There’s a regional and artistic movement toward maturation when you’ve absorbed the worst the world can offer. Then you try and build it back again. Real awareness as a person then an artist then a nation happens only once you know you’re mortal. The great things all happen after that.”

Chekhov and Whitman are also your dear ones.

“Yes, above everyone else. There’s something about Chekhov’s overriding wish to paint all of humanity, to take each case completely seriously, and yet no more solemnly than any other case deserves to be treated. Whitman was a nurse and Chekhov a doctor. If I couldn’t have been an artist, my wish was to be a doctor or preacher. But I didn’t believe in God (is that a drawback these days?) and I didn’t do too well in organic chemistry (that is a drawback). So here I am.”

The final novella in Local Souls, “Decoy,” is about a doctor viewed by the townspeople as a kind of deity. It’s amazing how a doctor in a small town could have such status because of his perceived Christic abilities.

“The smaller the town the bigger events loom. So do local heroes. In ‘Decoy,’ Doc Roper, out jogging, passes a neighborhood birthday swim party. Twin boys just turning six have drowned. He has them placed onshore side by side. That way, kneeling from above their heads, he can easily breathe into them at closest range. In minutes, Roper brings each back to life. These things happen every day in the world. But imagine what it does to your neighbor doctor’s reputation. If anything goes wrong at your house, you know that such a wonder worker is just one holler away. Doctors can take on a messianic small town function. John O’Hara, a doctor’s son, went on house calls with his dad and writes of these visits with great tender force. In ‘Decoy,’ I am speaking of our appetite for, indeed our addiction to, heroics. Not just for the General MacArthurs or the Gary Coopers, but the guy right down the block who can clear your air passages and bring you crashing back to consciousness.”

The adolescent Gurganus grew antsy to flee Rocky Mount, but not because he felt his roomy mind in rebellion against a minuscule town, or parochial air polluting such eager lungs. Rather, he harbored the organic curiosity of an artist and the very pressing wish to lay some miles between himself and his pious father, who had had a potent religious conversion when Gurganus was ten. A shifting away from mild Presbyterianism then took him headlong into the absolutist embrace of Born Again Baptists. “My father’s conversion came at the worst possible time. Just as I wanted to dance and smoke cigarettes and mess around with boys and girls and play cards and run wild, he wanted me to do none of those things. Pleasure was sin. I believed in the first not the second. Huge battles loomed. He was fighting for my soul. But I wanted it, too.” The origin of Gurganus’s lifelong lover’s quarrel with organized religion? It dates from this time. At the age of twelve he witnessed his congregation vote to exclude all the black worshippers. He understood then—immediately and pointedly—that the Church preached compassion while embodying judgment and exclusion.

Religion presumed possession of all answers. Literature? The humble and humbling labor of asking questions. Salvation in Gurganus’s work is always handmade and hard-earned. The teachings of a welcoming Christ stand at odds with the boy’s segregated church. In “Decoy,” narrator Bill Mabry remembers his father: “Red Mabry was edging us ever closer to full-blown watered-silk Episcopalianism. I think he believed that the air in All Saints’ stain-glassed sanctuary must be so rarefied … that, simply on entering, all our country noses would bleed.” His father held “raw belief. In the value of believing”—in other words, faith starts where the mind stops: his poor father simply refused to think. In “Saints Have Mothers,” Jean offers this caustic reply to the preacher who arrives with artificial solace after the disappearance of her cherished daughter: “Don’t you ever get embarrassed, Padre Tim?” she asks. “You go from death house to death house mindlessly repeating these duds they trained you boys to palm off on real adults with actual griefs? You didn’t have a coat and nobody’s blocking your car.” Less subtle, Hartley Mims in Plays Well With Others dubs God the “Lord and architect of suffering” who is also “succch a bad designer.”

“The first rule of Church is to preserve Church,” Gurganus tells me. “Everything is sacrificed to its organizational health. One thing I don’t understand, the role of women, gays, and minorities supporting the Church that has condemned them from the beginning. If every woman, including those in convent, stopped tithing, walked out of an organization that will not let a female touch the host and offer a sacrament, the Church would either die or reform overnight. We all participate in the mechanism of our own doom. How many priests are gay? Throw all gay people out of the Church, there are no organists, there is no Church. A Presbyterian minister said to me recently, Well, Allan, we’ve just admitted our first gay preacher. Credit where credit’s due. I said, Congratulations, that only took you two thousand years.”

His father’s stringent, punitive religiosity made it easy to leave Rocky Mount. At seventeen Gurganus gained acceptance to a joint program to study painting at the University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Life in Philly was, he says, “a rocket ride” he wasn’t quite prepared for—less culture shock than full-on culture electrocution—and he stopped school after a single year. But it was 1966 and America’s meddling in Vietnam was ramping up, and Gurganus was clueless about what leaving Philly actually meant for him. His Republican parents did nothing to discourage him from going to war. In fact, his father—as a veteran of the Second World War whose notions of valor were outright Homeric—thought Vietnam would be his son’s much-needed making as a man.

Gurganus was eighteen years old and chose the Navy because he’d read Conrad and Melville. “I figured it’d be a nice clean death if the ship went down. Fish food.”

It was on the USS Yorktown with its bloated library that he began reading his way from A to Z, partially in an effort to ward off despair as he struggled through this vassalage at sea. If he had learned to paint by mimicking the masters, he’d learn to write by doing the same. He fashioned chapters after Dickens, endings after George Eliot, whole stories after Chekhov. “I counted the words in each sentence and figured out where the verbs went. I did what every artist does to teach him- or herself.” When the war began decelerating, the Navy snipped his chains after three years instead of four, and by that time he’d read 1,200 works of literature and written book reports on each one.

A freed man, he fled to Boston/Cambridge for a year, then to Sarah Lawrence to study with the inimitable Grace Paley, the storywriter he most adored. “She was a genius, a person of so much depth and humanity. She never held it against me that I’d been in the military, though she worked as an anti-draft counselor.” Sarah Lawrence allotted him two years of college credit for the work he’d done in the Navy. This was his first opportunity to speak meaningfully about the books he’d read, about his own literary vista that was starting to expand before him. An invaluable tip in writing? He learned it while studying choreography in a dance class with the singular Bessie Schonberg: How does a dance end? It speeds up or slows down before it stops, which is exactly how a scene in fiction should end.

Few can match Gurganus in closing a scene with such lingering punch. In “Fear Not,” the first novella of Local Souls, Susan is found by Michael, the eighteen-year-old son she’d ceded at birth. After several anxious, enthralling pages of nuanced detail and visceral reckoning, their reunion scene ends with Michael asleep on her shoulder:

Susan even glimpsed some narrow footpath toward a future. Till this today, till him, she’d never much believed in one. At age fourteen, she’d had to downgrade. She’d seen her own childish Luck, cut-short, surrender to adult-discount Fate. Did Michael’s stepping in here reverse that? Might his cleverness in tracking her mean true Luck’s return? It now slept tipped close against her. Luck must weigh a hundred and seventy pounds, easy.

How could there have been so little love on earth just forty minutes back and now, this suddenly, so much?

Two years into his studies at Sarah Lawrence, Gurganus won a Danforth Fellowship to pursue graduate work and, in a fateful play, chose writing at Iowa over literature at Harvard. There he studied with John Irving and Stanley Elkin, but it was his friendship with and tutelage under John Cheever that would have such a determining effect on his life and work. Without the young writer’s knowing, Cheever mailed his story “Minor Heroism” to William Maxwell at The New Yorker. When Maxwell called Gurganus to accept the story and introduce himself, Gurganus responded, “Yeah, and I’m Mae West, who the hell is this?” In Blake Bailey’s mammoth biography of Cheever, Gurganus is quoted as saying that his teacher’s advocacy of “Minor Heroism” was “the kindest thing anybody’s ever done for me.”

“Minor Heroism” was not only his first publication but the first time The New Yorker had ever accepted fiction portraying a gay character. The significance of this cannot be overstated. The story might not concern the realities of gay life and all they entail, personally and socially—what Edmund White has named “gay singularity”—but it remains a harrowing portrait of a father slowly learning the dreaded fact about his son: “he has always had a real flair for the arts” (normally the first tip-off, those pesky and epicene arts); “Bryan does articles for a magazine called Dance World”; “the only women he ever talks to are waitresses.” When the father knows for certain, he reacts as only a gruff Greatest Generation combatant can: he pummels the boy about the head.

Gurganus was not only Cheever’s shining student but also the aim of his erotic advances. The Bailey biography carefully audits Cheever’s Journals to give the sole accurate assessment of their relationship. As Gurganus asserts in an essay on Cheever for the New York Review of Books—on the occasion of his teacher’s one-hundredth birthday—he was not “the boy that seduced Cheever in Iowa,” as the calumny had it upon Gurganus’s arrival in Manhattan years later. Bailey’s biography corrects the accounting on this and “treats my moderating role with moral clarity.” In his essay, Gurganus writes:

Forty years later there’s this concept called “sexual harassment.” A professor trying to force himself upon his student is fired at once for the worst sort of poaching. But something in the fumbling, hopeless way John attempted it let me know he was seeking some last chance. Instead of preying on me, I sensed he was trying to show me his very best. He meant to demonstrate all he might have been if born into my generation.

They remained friends for the rest of Cheever’s life, which proved a scant ten years thanks to that familiar unstringing, the poison with which he daily blitzed his liver and lungs. What could an aged, old-fashioned, faux-aristocratic New Englander alcoholic possibly have had in common with a vivacious twenty-five-year-old comic writer from the South? Literature, most obviously. But there’s also this: reading through Cheever’s Journals—Gurganus has described them as “a ten-thousand-page suicide note”—it’s easy to forget how funny Cheever can be in his stories (revisit “The Worm in the Apple” if you have your doubts). The great man, Gurganus believes, has become “unfairly known as the gloomy, sodden satyr of suburbia,” but “fact is he was more fun per minute than is legal in a nation this Republican.”

How emotionally complicated was your reaction to Cheever’s death? Blake Bailey’s biography describes you as the last to leave his funeral. He also mentions that on the day you learned Cheever was dead, you were at Yaddo and found a letter from Cheever waiting for you.

“I knew from the start that I wanted Cheever as only a mentor-teacher, as a friend, but certainly nothing else. There was a vast difference in our ages (he was born in 1912, I in 1947). We had wildly varying attitudes toward being gay. All this presented an unbridgeable chasm. I admired his prose, knew his work chapter and verse, and truly enjoyed the vigor and wit of his company. He wanted more but I persisted in resisting that. Blake Bailey’s telling is the only fair one to date. I was at Yaddo when I heard the news of his death, ‘Famous American Author, John Cheever, succumbed today at his home in Ossining, New York.’ I sat stunned on the edge of the bed. I finally went downstairs to breakfast and there, on the mail table, was a letter from him. It contained a generous endorsement of my writing’s force and future. It seemed a loving father’s timely send-off, a hat-tip from beyond the grave. I still have the letter.

I couldn’t get any of my fellow Iowa students to drive to the funeral with me. But I borrowed a car and got to Quincy, Massachusetts, early. I saw three guys digging the only new grave in what looked like a colonial cemetery. I assumed the slot must be John’s. After the funeral and even before the graveside rite started, Updike chose to give a press conference, standing so near the open hole, dirt kept falling in.

There was a family party afterwards. Graveside I spoke to Cheever’s widow, Mary, and his kids but was not invited back to the house and had not expected to be. Instead I just hung around the graveyard, thinking my thoughts, feeling grateful for John’s faith in me, his kindnesses. I watched those same workers, guys that’d hand-dug the grave, now fill it back up. One of them, shirtless, blond, about twenty-two, handsome in a larky Irish way, did most of the backbreaking work. Fellows had no idea who they were burying. The young gravedigger kept leaning on his shovel, joking with the older men who often slowed to smoke. This one boy’s beauty, exerted and enlarged by topping off John’s coffin with a hundred pounds of dirt, seemed his one joyful parting benediction.”

As in Confederate Widow and much of Gurganus’s shorter fiction, the sensibility of Local Souls might be aesthetic but there is no gay special pleading. The book offers suburban heterosexual culture a sympathy it has often withheld from the urban homosexual world. Part of what marks Gurganus’s walloping talent, and what sets him aside from the pool of his contemporaries, is his tendency toward the chameleon, the protean, the ecumenical. He has never been a mere creative writer, indulging all the vaguely therapeutic and narcissistic elements that term can imply. The phrase often gives precedence to personal experience and the identity-despotism of write what you know. Rather, Gurganus has been from the beginning an imaginative writer, a Wordsworthian celebrant of the Imagination’s transformative refulgence. Acts of imagination are, at their core, humanizing endeavors. For this reason Gurganus resists writing from only the well of his minority identification, or even the tallied facts of his own life as a Vietnam veteran and a plague survivor. There’s almost no facet of our humanity that goes unexamined by his delving eye: history and class, race and family, God and nation, sexuality and gender, city and country, disease and friendship. Fearless, he seems. He doesn’t wave flags, rainbow or otherwise. His one agenda is art. This versatile dramatic facility renders him immune from pigeonholing. It also makes him one of the most exciting fiction writers alive.

He tells me this: “Gay people that write only for and about gay people who love Donna Summer and Judy Garland and Broadway musicals have painted themselves into a terrible self-segregating corner. That’s like choosing to be a minstrel-show African American, Sammy Davis Junior doing the Al Jolson mammy routine. It plays to an expectation that says all gay men are sissies, when some of the strongest and most athletic and brilliant people in the world happen to be gay people. I want my work to be broader than that.”

In “Decoy”—a novella that boasts the execution and breadth of a full-length novel—Bill Mabry at times has a partial awareness that his worship of Doc Roper, ten years his senior, has something slightly homoerotic about it. (“Mabry” smacks of “maybe” for a reason: his entire life has been one drawn-out maybe, from the heart disease that killed his father and might kill him next, to his longed-for friendship with Roper, a friendship always on the cusp of becoming actual.) But all of the Fallen have fallen for Doc Roper and his somatic wizardry; Mabry isn’t special in that regard. “Us around here? We’re kind of funny about our doctors.”

Much of the significance of “Decoy” lies in its depiction of how average men actually feel about great men—the great men we could never be, the great men we were too inadequate or unlucky or cowardly to become. (Wilde: “One’s real life is often the life that one does not lead.”) How many millions of “straight” American males experience the warm surge of eros at the mere mention of their heroes’ names? Jack White and LeBron James, Tom Brady and Tiger Woods, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen and Cormac McCarthy—the prestige and wealth of these great men are made possible mostly by the adoring support of not-great men. How many males sustain deeply emotional, even affectionate friendships with other straight males? Martin Amis often spoke of his friendship with Christopher Hitchens in romantic tones, describing it as “an unconsummated gay marriage.”

Miffed at being snubbed by Roper one afternoon, Mabry laments: “He had no idea what-all he meant to me, but then did I?” On one level Mabry knows precisely what Roper means to him: everything that Mabry himself could not achieve, and his wanting to be close to the famed doctor is a wish to be near that version of himself that once waltzed in his dreams, before life got involved and turned him into an ordinary insurance salesman. Men want to be near their heroes in an unconscious attempt to absorb some of their force, to siphon off some of their godliness so they themselves might finally feel worthy of the world. Would Mabry have been a success like Roper, the object of adulation and awe, if he had abandoned Falls for more glorious locales? Here’s the question he asks near the start of his chronicle: “And folks that left at age eighteen—even ones now well-known artists in New York—you think they’re a bit happier?”

You get the feeling it’s a question Bill Mabry doesn’t want answered.

Gurganus’s own arrival, his debut, in New York was somewhat roundabout. In 1975, after Iowa, he won a coveted Stegner Fellowship at Stanford. Reynolds Price then coaxed him back to North Carolina, to teach at Duke University, where he stayed on for three years. Next Grace Paley called: she hoped he would come to New York to teach at Sarah Lawrence. Gurganus, elated, leapt to Manhattan. Paley’s offer was an enormous honor; though his stories were appearing in The New Yorker and The Atlantic, he hadn’t yet published a book (Confederate Widow was underway). He commuted to Bronxville twice a week while living first in Chelsea, then in Hell’s Kitchen—where the neighborhood was so sinister he either sprinted to avoid muggers or else padded himself in extra clothes and feigned a hobo’s lunacy. He finally landed in the apartment that would be his for the duration, at 90th and Amsterdam, where the rent remained a surreal $260 a month. It was 1979 and he’d beaten HIV to the city by only three years.

In Plays Well With Others, Hartley writes: “You must hail from rusticated eastern North Carolina—its topography flat as a table—to understand how very much the erect and steely city truly means.” For Gurganus, in these few years before the scourge, the city meant saturnalian exuberance and experimentation; it meant the hourly love of art and friends; and it meant an ecstasy of being alive and among so much talent despite being breadcrumb-broke. (Hartley: “Our patron saint was Saint Adrenaline.”) The Dionysian abandon with which Gurganus and his cherished compeers romped through Manhattan was so beautifully excessive it could not possibly endure. “Maybe it was my Presbyterian upbringing,” he says now, “but I remember thinking that this was bound to end badly, that it was more than any of us could be granted. It was a freedom that would never ever happen again. The outer swing of the pendulum.”

The malediction hit and the celebration stopped; death replaced bliss and partygoers became caregivers. From 1982 to 1992 Gurganus was willing nurse to thirty dear friends. He denies any sainthood for shepherding so many young men to their deaths because he wasn’t alone in doing it: the spared rushed in to help the stricken quite simply because there was no other help to be had. Reagan, remember, decapitated funding for AIDS research, bracketed himself with scurrilous bigots such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson (both of whom believed that AIDS was God’s necessary wrath on gay men), and only after six years and roughly 20,000 deaths, including Rock Hudson’s, did Reagan feel pressure enough even to utter the acronym in public. Gurganus: “Don’t talk to me about the heroic gentle Reagan. I can tell you otherwise.”

Gurganus, guided by the examples of Dr. Chekhov and Nurse Whitman, developed a new idea of manliness. He smiles about his generation’s cowboy novelists who pride themselves on imagining they’d be brave under pressure. “Some of these guys, they fired a twenty-two once on their uncle’s farm. I was considered the precious artist while being the surviving Vietnam vet now taking care of my fellow fallen foxhole pals. You choose your definition of what constitutes the truly manly.”

That decade of death in Manhattan had its numinous side. The mobilization of the gay community in service of the sick was astonishing to behold, “a true people’s movement,” as Gurganus calls it, “a joy and honor to be a part of.” The oldest of four brothers, fulsome by default, he fit easily into the clothes of guardian/caregiver. And about being spared when his rollicking was no different from those who perished? “I know all about being lucky. I went to the Vietnam War and I lived. I went to New York and served in the pandemic that wiped out my community and I alone survived to tell the tale.”

Kafka called virtue “disconsolate,” although Hartley Mims makes his virtuous service to his wasting friends as blithe and colorful as they were when healthy. But Gurganus won’t credit virtue for his survival, despite his years-long selfless allegiance to the stricken. “It has nothing to do with virtue. I considered myself a sexual pioneer, an equal opportunity employer. Goodness didn’t spare me. Some roll of the dice did.”

In Plays Well With Others, Hartley says he needs to “find some way to make Comedy of this shuffle toward the crypt.” Likewise, in “Saints Have Mothers,” an irreverent stand-up despair is crucial to Jean’s dealing with her daughter’s disappearance. I’m always stupefied when I hear comic writing denigrated as inferior to tragedy. The truth-tellers in every culture are exempted as comedians. Only they risk candor and their heads—the fool in King Lear, the gravedigger in Hamlet. Look now at Jon Stewart, Chris Rock, Sarah Silverman.

“I think of myself as a comic writer. I look back to the original meaning of comedy, from komos, meaning a ritual pageant or village dance. Extremely beautiful to me, this communal rite of choreography. I view comedy as a higher form than tragedy. It leaves us a few more choices. Tragedy is a trap walked into, brought on by hubris, baited by destiny. Oedipus is blind before it. Comedy sees too much. Sure, it admits to a kind of despair, but at the same time it offers a solvent and resurrection called laughter, the possibility of continuance. Groaning laughter is often our sole salvation and way out. That’s my own vision, chuckling unto screaming is how I get through the worst days. Remember what happened when Kafka read aloud to his friends from his tale The Metamorphosis? Poor guy cackled so hard he had to stop, go for a walk around Prague to let his mirth out. And his great story is hilarious, once you get past the ick factor. Jokes are mousetrap mechanisms, easy to make and famously forgettable. But, to be strenuously funny about something, that is a profound undertaking. When it occasionally works it is a great service to one’s species. Think of Waugh, Wodehouse, Wilde. Cats cannot make jokes about other cats. We are the only animals with this doubled capacity to take ourselves seriously while sending ourselves up. I see that as shorthand for our spiritual capacity.”

In a recent interview you said, “I lock onto my characters’ spiritual hunger. Loyalty to that pulls me to the true narrative marrow of their lives.” I’ve often found myself explaining how such longing hunger can exist independent of Church-bound belief in any sea-splitting abracadabra. Just as history is too good to be left to mere historians, spirit deserves more than priests. Your work reaches the sublime partly because it sidesteps the limitations of “realism”—those faux-Carverian kitchen-table dramas. The rent is due, the marriage is shot. Your work admits to, yearns for, a deeper and fuller mode of being.

“I do hope so. That is a huge concern of mine off the page. I think we all wake up hoping that today our true lives will finally begin. Some might say there is no such thing as a secular soul. I disagree. Maybe self is the truer word for soul. I try imagining a self-soul independent of any defining reward or punishment meted out in a Christian heaven or hell. Surely we are more original than original sin. What a nasty half-truth and how much damage that has done to those of us who grew up churched. Surely we are all endowed by our Creator, whether there is one or not! If not, the novelist’s job-slot sure upgrades in its urgency!”

Spiritually and bodily sapped after burying so many beloveds, including his own boyfriend, Gurganus abandoned New York in 1992 and returned to North Carolina. He’d just been given tenure at Sarah Lawrence but tenure wasn’t half enough to keep him there amidst the lingering of such ruin. The unholier the wreckage of one’s life, the more stubbornly present that wreckage remains in place. He yearned now for oxygen-rich real estate. His version of his grandfolks’ family home. A garden sounded nice. Occasional quiet, too.

He hunted for such a place in Chapel Hill but every price tag had one zero too many. A miniature of Rocky Mount, the town he finally chose remained relatively undiscovered: it felt—and still feels—like an eighteenth-century village. Here he found a wondrous 3,200-square-foot Victorian with pronounced Arts and Crafts elements built in 1900 for the local doctor. Gurganus has fashioned his home into a phantasmagoria of Americana, a chromatic shrine to the godhead Art. You need an entire eye-indulging day to appreciate all the marvels on view. A sample:

His workroom at the rear of the house has large arrowhead-shaped painted-glass windows from an 1840s Episcopal church. Proust keeps watch from a portrait; clergymen and French generals stand guard in others. Sculptures and busts pose atop column pedestals, including Saint Ursula (she of stoned-to-death fame). Half the back wall contains a stained-glass window, rounded at top. To its left, an exquisite English oak hutch, circa 1820, in the shape of a fortified castle. Above, light fixtures hanging from the vaulted ceiling, procured from a deconsecrated Presbyterian church. The heavy wooden doors leading into his library? Those are the original doors from the Episcopal church. Inside the library: a phalanx of globes, statues and statuettes, more busts, and a terrific diorama of a Greek gymnasium. Those are regal-looking bishops’ chairs. “For a card-carrying agnostic,” Gurganus tells me, “I was not unaffected by the church. Christ’s parables inspire me daily. My work is an attempt to answer those big old catechism questions with a few new answers.”

In the foyer hangs his collection of American Federal period mirrors, elaborately framed. In the dining room sits an assembly of antique chairs, including 1890s Chippendale chairs he inherited from his godmother. That wallpaper is the garlanded original 1900 paper. The Robert E. Lee signature photo was a gift from actress Ellen Burstyn, who played Lucy in the Broadway production of Confederate Widow. Near the ceiling, a plate rail displaying a row of unusual plates, including one from the Edmund Wilson household, a gift from his talented painter-daughter, a plate on which the eminent critic most certainly enjoyed red meat. Under us, rag rugs and orientals with every step: Gurganus calls them “unacknowledged masterpieces.” Onto the hallway walls of the second floor he painted the Elgin Marbles, the magnificent procession eight feet high, galloping from one end of the house to the other. “It’s been a joy to live here. It’s a cohabitation.”

This abundance of art on every side of him comes as no surprise. His fiction is suffused with Western painting (John Singer Sargent is central to “The Practical Heart”). Look close enough and you’ll notice that Gurganus designs a crowd scene after Caravaggio (see the post-flood gymnasium scene in “Decoy”), a close-up still-life after Chardin (see Doc Roper’s decoy ducks), a portrait after Rembrandt (see Michael, the returned son in “Fear Not”). Music, too, sounds throughout his pages (Robert Gustafson, one of the three leads in Plays Well With Others, is a composer who’s spent salacious weekends with Aaron Copeland). Bach’s deathless tones can be heard from Gurganus’s house in the gloaming, his fugue-power felt in every quadrant of his fiction. Such oblations of art align Gurganus with the Thomas Mann of Doctor Faustus and Death in Venice: Aschenbach’s music, writes Mann, contains “an almost exaggerated sense of beauty, a lofty purity,” and if there’s a better description of Gurganus’s prose, I’ve never seen it. There’s a sense in which he believes that any separation between one art and another is artificial and unneeded.

His house of art, this respite from the hurly-burly and curse he’d seen, was not possible in Manhattan. He’d originally thought of this home as a hiding place, but “the world has a way of calling you out of your cave,” and he greeted a new community here after losing his gifted community in New York. It’s apparent at once how loved he is in this town; he can’t amble half a block without pausing to exchange hugs and pleasantries with neighbors, friends, fellow villagers. His dearest friend of more than forty years, the artist Jane Holding, lives nearby, as do the writers Lee Smith and Randall Kenan and Michael Malone and Jill McCorkle, the Duke documentarian Tom Rankin, and the living godmother of Southern literature, Elizabeth Spencer. When we met Spencer for dinner one evening she brought Gurganus a gift: a printed photograph of W. B. Yeats she’d discovered that day online (she wrote her graduate dissertation on Yeats at Vanderbilt in 1943). At ninety-two, Spencer is so handsome, charming, graceful, and wise, many a sorority minx could learn heaps of class from just six minutes in her presence.

Our culture is gender-obsessed because gender is usually the easiest element of any issue to fix on. Inevitably some critics will marvel at your capacity to craft such convincing women in Local Souls—something you’ve been doing all along, right out of the gate with Lucy Marsden in Confederate Widow. And haven’t male writers been creating blood-and-bone women since the birth of literature, Medea and Clarissa and Emma Bovary for starters?

“It’s extraordinary that it is considered a feat for a male human to actually imagine a female one. Fifty-one percent of human beings on earth are women, right? We’ve all spent nine months riding around in the belly of one, and yet when it comes to writing I and thinking she—impossibility looms. Just shows you the depth of misogyny in our culture. There are seventy pitchers in the Baseball Hall of Fame and only sixteen catchers. Might this not show you what a diminished role the receiver in sexual relationships gets accorded? And the catcher, she’s calling the shots on the pitcher’s mound! Just as in a marriage. And yet where is her position of honor? It’s always the pitcher. For me it’s more symphonically enjoyable to write in the voice of women because women, especially in a first person and close third person confessional, can admit to more various contradictory and enlarging emotions.”

Because the culture grants them permission for such effusiveness, whereas effusive men are viewed as effeminate, not quite up to the task of manhood.

“Exactly. Men have been taught a hesitancy to say overt emotional things. It’s all demonstrated. In the case of “Decoy,” it’s all about creating objects that are admired, coveted by other men. That’s the medium of male emotional exchange. It’s fascinating, a stock exchange of goods and skills. One of the things I realized when I was writing Confederate Widow, and trying to differentiate between the voices of the captain and his wife, is that men measure things when telling a story, using literal, numerical measurement, whereas women have a wider emotional range. They’re more resilient, more resourceful, and have more depth of spirit than most men. Of course there are exceptions on both sides, present company included.”

It’s 1952 and the boy is five. He strolls along in the surf at Wrightsville Beach in North Carolina. He doesn’t know that one day earlier a riptide carved a twenty-foot trench where he now walks. There’s no time for breath. He drops vertical through bubbles. He can’t swim and tries to wiggle, a tadpole, up toward the light. Within seconds the boy resigns himself to dying. He thinks: Well, I had a good five years. A nice house, a nice yard, an excellent dog. He’s suspended there underwater, a full minute into dying. Then a hand smashes through from above. The hand bonks his head, startles him from dying, then yanks him up and out into the air. The hand belongs to his father. Gurganus, an ex-sailor, is still convinced that his death will be by drowning.

He grew up in a town with a river and knew that sense of mysterious distance a river gives, other realms left and right. If there’s one conspicuous image, one unappeasable force, pervading Local Souls, it’s water. The duality cannot be ignored: what saves and what destroys; what gives life and what takes it. Experts will tell you that water damage beats fire damage in the contest of calamities. The River Lithium canals through the town of Falls in all its bipolarity, in its alternating moods of sooth and sunder. In “Decoy,” Bill Mabry says, “It wasn’t just the water’s doings that seemed bad. Water itself was.” In “Fear Not,” Moonlight Lake becomes the scene of a ghastly motorboat accident. In “Saints Have Mothers,” an over-swollen African river abducts young Caitlin Mulray.

If the promise of death permeates Local Souls so too does the promise of resurrection. The post-lapsarian, O’Connor-esque ethos is augmented by the Fallen’s unstoppable urge to continue, to rise above the ruin they might or might not have brought upon themselves. In this typical Southern town, typical but tangled characters undergo Wagnerian transformations. What descends upon these average citizens matches what descends upon exalted kings in Athenian drama, and through their resilience, their harnessing of the vigor to persist, to fend off extinction or despair, they themselves become exalted. John Irving calls Gurganus “Sophocles in North Carolina.” And yet Falls is no American outlier, no annex of antiquated struggles, but rather a microcosm, a shrunken stage on which our colossal American subject matter struts, vaunts to redefined victories.

We’ve come to expect Gurganus’s expert architecture of wholly human characters, but Local Souls achieves a new level of mastery: he knows these people better than most of us know our own family members. The parental insights and careful attention to the lives of children, in particular, shine with such profundity, such accuracy, that one turns pages in disbelief that Gurganus himself is not a parent—more evidence of his bountiful imagination, his assimilating of all human interaction. In “Saints Have Mothers,” Jean says, “You can be so afraid for somebody, you grow half-scared of them.” Later, she says about all parents: “What we do is self-engineered obsolescence. Once you teach your kids to (1) love, then (2) leave you, your job on earth is done.” There’s a tremendous moment, after Caitlin’s disappearance, when Jean’s scallywag ex-husband insults her appearance, and one of her twin ten-year-old boys responds to his father, “Mom’s been brave. And saying that was mean.” Her son’s defense of her nearly topples Jean with pride. Gurganus observes this family’s undoing and revival with an exhilarating tenderness.

The book could just as well have been named Those Who Stayed since the nexus between novellas is the everyday heroism—the minor heroism—accomplished by small-towners who understand that fleeing to the rumored utopia does not necessarily mean contentment, never mind glory. They understand the dignity, the bantam integrity, that can follow from remaining on the very soil that nurtured them. Bill Mabry calls the Fallen “us souls born to stay local”; he also notices that “if a person doesn’t fight gravity, it wants you right where you have been.” Mabry’s fascination with Doc Roper derives partly from the fact that Roper, Yale-educated and already paroled from the province of Falls, somehow chooses to return.

“Returning to North Carolina made me know how much I’d changed,” Gurganus says. “When I left home at seventeen for school up north, I assumed that heroics belonged only to Those That Leave. Saint George trotted off to seek every dragon along Route 66. Once I was replanted in red native clay, I started seeing the merit and nerve of the ones who hang around to look after aging parents, the ones that got pregnant out of wedlock or inconveniently early. The small-time inheritors with a stake just big enough to keep them staked to that first spot they knew. Observing momentous woes visited on educated well-meaning locals—that can produce something as marble-countertop-contemporaneous as it feels marble-crypt ancient, ancient, ancient.”

Among the many pleasures of Local Souls none gratifies more than its prose. Of living novelists in English, only Martin Amis and Cormac McCarthy can match Gurganus’s pyrotechnical aptitude for language, for forging a verbiage both rapturous and exact. He’s categorically incapable of crafting a dull sentence. Moreover, there’s nothing like a wise writer, and the wisdom in these pages strikes with adder-like alertness: “What big cities might call Sadism little towns name Fun”; “At eighteen he looked almost disabled by handsomeness”; “Maybe the harder you avoid a thing, the greater its impact incoming”; “Disaster makes you doubt every decent thing that stretched back safe before it”; “Loyalty goes unrewarded when you’re seen as one who’ll stay no matter what.” Always entertaining, Gurganus is not simply an entertainer. He offers a vision predicated on the very moral precepts his beloved, disappointing church proposed then failed to impose on itself. How shall we live? What do we owe one another? How can a world this funny and beautiful kill every one of us? In a publishing climate where indolence and laxity reign, where lameness and cliche are granted their pitiful say, Gurganus emerges as something of a savior, as a nineteenth-century throwback with the future trailing him.

Local Souls had an enthusiastic savior/facilitator of its own in the irrepressible Robert Weil, head of Liveright Publishing, a relaunched wing of W. W. Norton. Weil, a legendary last-of-the-breed editor with Malcolm Cowley’s intuition, was partly responsible for resuscitating the career of the great Henry Roth, author of the masterpiece Call It Sleep. At a dinner for the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2009, poet J. D. McClatchy introduced Weil to Gurganus and their friendship began instantly. Reached by phone, Weil tells me that he trekked to North Carolina to visit Gurganus not long after they met and was stupefied by the mounds of manuscripts stacked in his workroom: Gurganus might have extricated himself from publishing, but he’d been writing—daily, furiously—in the decade or so since his last book had appeared. Weil said, “Allan, what are you doing?” and emboldened him to put together a new work or two and return to publishing. When Gurganus’s agent made Local Souls available for sale, Weil and Liveright stood ready. “Bob Weil,” says Gurganus, “works as hard as I think I work. He publishes only writers he respects. He goes on to revere and champion them—after editing and presenting only their very best. If we were passengers on a sinking Titanic, I’d comb the decks for Bob. I would want Weil’s ethics, energy, and know-how in my lifeboat.”

Next year Liveright will publish Gurganus’s new and collected stories. What’s it feel like to be back? “It’s like jumping into a pool, after being high and dry ashore for a decade, and knowing so unconsciously all the strokes and moves and kicks needed to stay afloat. Convinced you are, in fact, under everything else, a porpoise.” And the new novel that’s been in progress for so, so long? There’s about fifty pounds of it piled in a corner by Gurganus’s desk. It looks resplendent waiting there for another octopus-embrace of the world. “Maybe I survived for a reason,” he says. “My work is surely my fate and whatever chance I have at immortality. In the books some of my strengths and all my faults are put on pitiless display. The work is my attempt to save my departed friends, both souls and selves. Art is the parallel religious force in my life. What others invest in their prayer lives and churches, I have taken straight into stories, beloved phantoms made from twenty-six letters of the alphabet. Such work, for me, is sufficient unto the day.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.