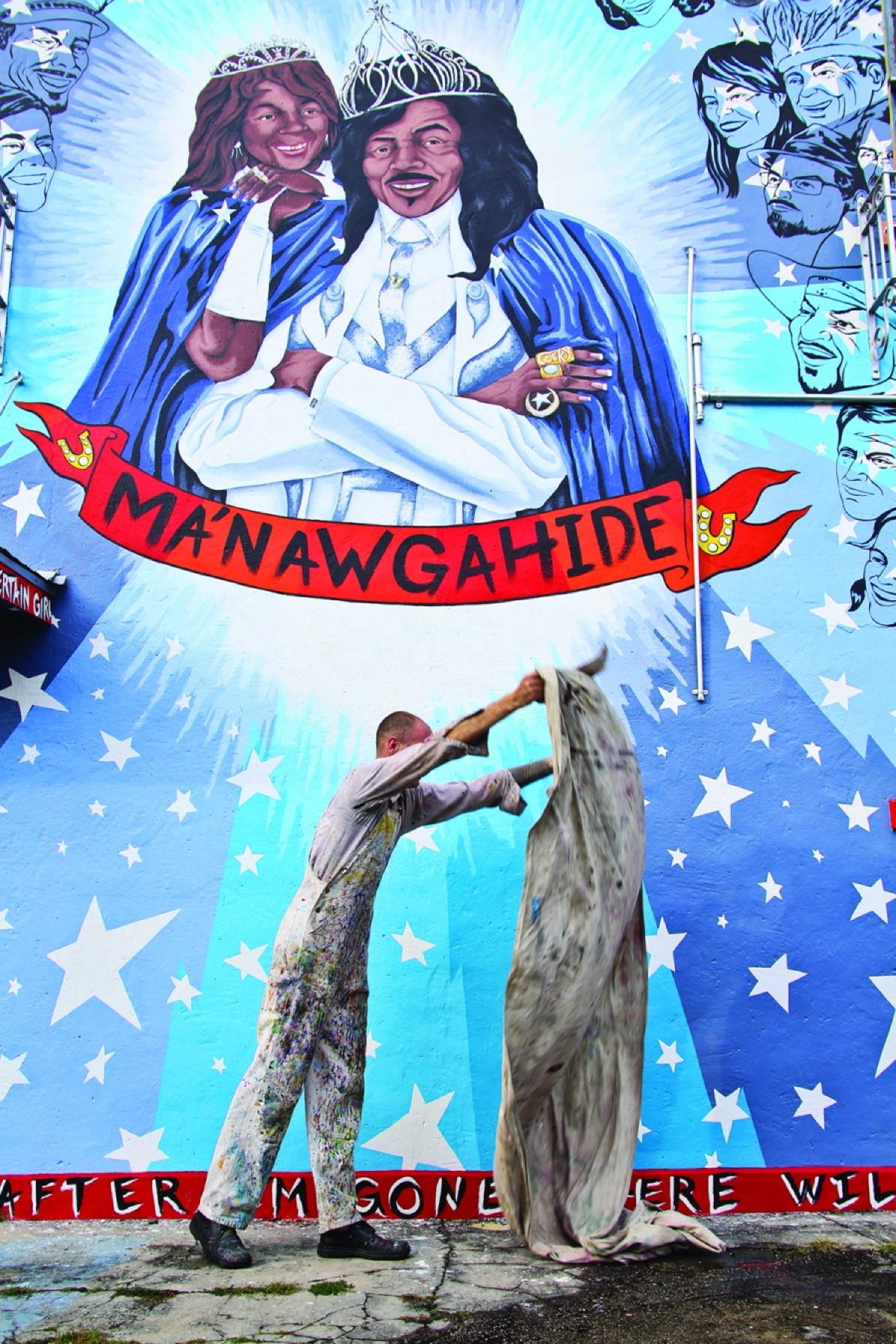

Photograph of Daniel Fuselier by Zack Smith

The Man on the Ladder

By Michael Patrick Welch

Seems like nothing will bring DanielFuselierdown from the ladder. He’s taken breaks from time to time since 2002, when Miss Antoinette K-Doe invited him to paint the exterior of New Orleans’s Mother-in-Law Lounge, but most weeks he can be found two stories up, a tall, thin, white man in a sun hat and paint-splattered overalls, at work on his Southern Sistine Chapel. Daniel’s canvas is shaped like acamelback MardiGrasfloat: one story around front, two stories around back. By now, brightly colored scenes of local music legends traced in thick black lines cover every surface visible from Claiborne Avenue. Wrapping the building in a full-body tattoo helps Daniel battle his lifelong depression, and he all but admits he’ll never finish the project. Never mind that he hasn’t been paid for the mural. He even buys his own paint.

Ernie K-Doe’s “Mother-in-Law” was the first #1 hit out of New Orleans, in 1961, but the singer floundered when his career stalled. Meeting Miss Antoinette helped him control his drinking and take the stage again, and they opened the bar in 1994. Seven years later, cirrhosis killed Ernie, and Antoinette remade the lounge in loving tribute to her husband: his microphone lay preserved in a glass case near coffee cups and souvenir handmade pillows bearing images of the couple. In a wheelchair sat a wax statue of Ernie that Antoinette took as her date to awards shows. But as much as it looked like a small-scale David Lynch–imagined Hard Rock Café, the lounge was really just a comfortable and dimly lit living room for black and white locals alike, all of whom came for great music, endless red beans, and a loquacious and (mostly) kind host.

Daniel first walked into the Mother-in-Law after a bad day painting houses. Battling a deep depressive episode and lacking friends, he was glad to meet Miss Antoinette and flattered she took interest in his art. That very night, she began helping Daniel land his dream job paintingMardiGrasfloats. Within days he was prepping her courtyard wall for the first mural. On the one-year anniversary of Ernie’s death, Daniel began his urban folk-art portrait depicting an embrace between Antoinette, Ernie, and Antoinette’s mother—and as he worked, Antoinette told stories describing her husband as virtuous and selfless. Daniel idealized the man, becoming obsessed with a deep artistic archetype that has fueled him for eleven years.

“I got addicted to using K-Doe as a muse to direct feelings that I have about being human and to address what humans need, crave, and desire—which is respect,” Daniel explains. “Ernie was someone who very much desired respect and was hurt at how things went with his career. He ended up getting really down and out, and it was a slow climb out of that hole.”

After he finished the portrait of Ernie and Antoinette and her mother, Daniel climbed the front of the building to paint the oldest and most famous Mardi Gras Indian, Big Chief Tootie Montana, flanked by his wife, Joyce, and Ernie and Antoinette, all in Indian garb. While Daniel painted, Tootie himself would sometimes come and stand outside the lounge, silently watching Daniel work on the six-foot-tall headdress. Big Chief lived long enough to see Daniel finish his likeness before dying in June of 2005. Months later, my wife and I evacuated to a stranger’s house in Florida to watch our city flood live on TV. New Orleans’s apocalypse played out on a flat, dirty brown canvas upon which we recognized almost nothing of the place we’d known so well—except for Tootie’s and Ernie’s giant heads, up to their necks in water, smiling as if at the beach.

After Katrina, Antoinette rebuilt and reopened the lounge, while Daniel scaled and removed all the building’s stucco. He began on the building’s biggest surface, the two-story wall on Columbus Street. “It was hard work because I didn’t have money to buy a hammer drill,” he recalls. “I chipped off eighty percent of that two-story building with a five-in-one and a hammer before I broke down and bought a hammer drill.” At the time, Daniel couldn’t pay rent; every year after Mardi Gras, float painters suffer through several months of unemployment. During this time in 2006, Daniel spent his days painting the lounge. At night, he squatted in a blighted Ninth Ward house.

Most of the lounge’s walls were white when Antoinette’s business came back to life, and she instructed Daniel to fill the Columbus Street wall with a detailed chorus of characters—friends and acquaintances and important people from Ernie’s career, from Al “Carnival Time” Johnson to psychedelic rapper MC Tracheotomy. The figures travel counter-clockwise around a focal point of Ernie and Miss Antoinette as King and Queen of the Krewe du Vieux parade. Against a blue background that denotes heaven, the dozens of transparent faces each sport a big star around one eye—all but Daniel’s own self-portrait, which he painted plainly behind a pipe. More visible is a bald white man: Oscar Fuselier, Daniel’s father, brutally murdered in 2007.

On the post-Katrina hellscape, the elder Fuselier was picked up by the police for missing a traffic court date in Jefferson Parish, then thrown into a hot cell packed with violent offenders. Oscar had PTSD after serving in Vietnam, and smoking had given him lung cancer—so he might have died in jail anyway with no air-conditioning and nowhere to lie down or even sit. But it was Richard Jackson who killed him, an eighteen-year-old armed robbery suspect who reportedly took issue with Oscar blocking the cell’s one fan. The teenager beat Daniel’s father into a coma from which he never woke.

Two officers remained on guard outside the hospital room where Oscar lay dying, handcuffed to his bed as if he might run off and skip traffic court again. This scene helped prompt Daniel’s decision to move away from the area his family had inhabited since before the Louisiana Purchase: he had to get out of this fool city in this idiot state. Despite a deep and burdensome Louisiana loyalty, Daniel realized that the same type of incompetence-cum-criminal-negligence that had caused the broken levees had also caused his father’s death. It would always be this way, he believed, and he needed to fucking leave. Just as soon as he finished the lounge for MissAntoinette.

Bad luck piled on as Daniel contemplated his next move. He fell fifteen feet from a ladder balanced atop a scaffold on a broken, sloping sidewalk. Then Miss Antoinette survived a bad stroke. She returned to work wilted, walking and talking slowly, but in 2009 she died on Mardi Gras morning. The lounge’s ownership shifted to Betty Fox, Antoinette’s adopted daughter, who struggled with the bar’s slender economics. Meanwhile, Daniel painted one-man-band Quintron, stomping and shouting behind his organ and backed by Miss Pussycat on maracas—until a car crashed into the wall, taking out the Mother-in-Law’s front door (the fifth such accident to the building, Daniel claims).

Though he’d been reticent to start a legal battle that would surely play out in the Times-Picayune, Daniel quit his job as a float painter to work on the lounge and focus on suing the sheriff’s department for his father’s wrongful death. The suit settled out of court, and Daniel took home a high five-figure amount after hospice and attorney fees. The DA’s office told Gambit Weekly that though Jackson eventually got six months for parole violation, he never served time for Oscar’s death; they didn’t receive the proper files.

But something strange happened once Daniel finally got the money to move away: he didn’t want to leave. His obsession with Ernie remained, and he’d become emboldened by the idea of his artwork being written into the history of the sameTremé neighborhood that had forged so much of American music. So he bought a house off Elysian Fields. “I just knew I would get homesick and end up coming back, and I was scared I couldn’t get a job without a college education,” he admits. “But I also partly felt like I was just running away from my problems.”

During her one year of ownership, Fox dipped into her retirement funds to keep the lounge afloat before giving up in the summer of 2010. “Whenever I see them I get emotional,” Fox says of Daniel’s murals at the Mother-in-Law, not far from her Tremé home. “I always turn on Esplanade so that I don’t have to pass, ’cause when I pass it I get all teary eyed.”

The Mother-in-Law remained dark until beloved New Orleans trumpeter Kermit Ruffins signed a long-term lease and reopened the club during this year’s Jazz Fest. Ruffins renamed it “Kermit’s Treme Mother-in-Law Lounge,” and he asked Daniel to add his visage outside the front door. Daniel agreed, though he has yet to ask the new owner about payment.

After the opening, Daniel climbed up the ladder to the second floor to begin chipping away at the bubbling, ten-year-old image of Tootie Montana. He claims he need only repaint that single scene, just one last time. Having already painted four of the lounge’s walls at least two times apiece, he says he will finally be done when the portrait is fixed. Then he tells me about his idea for the back of the building.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.