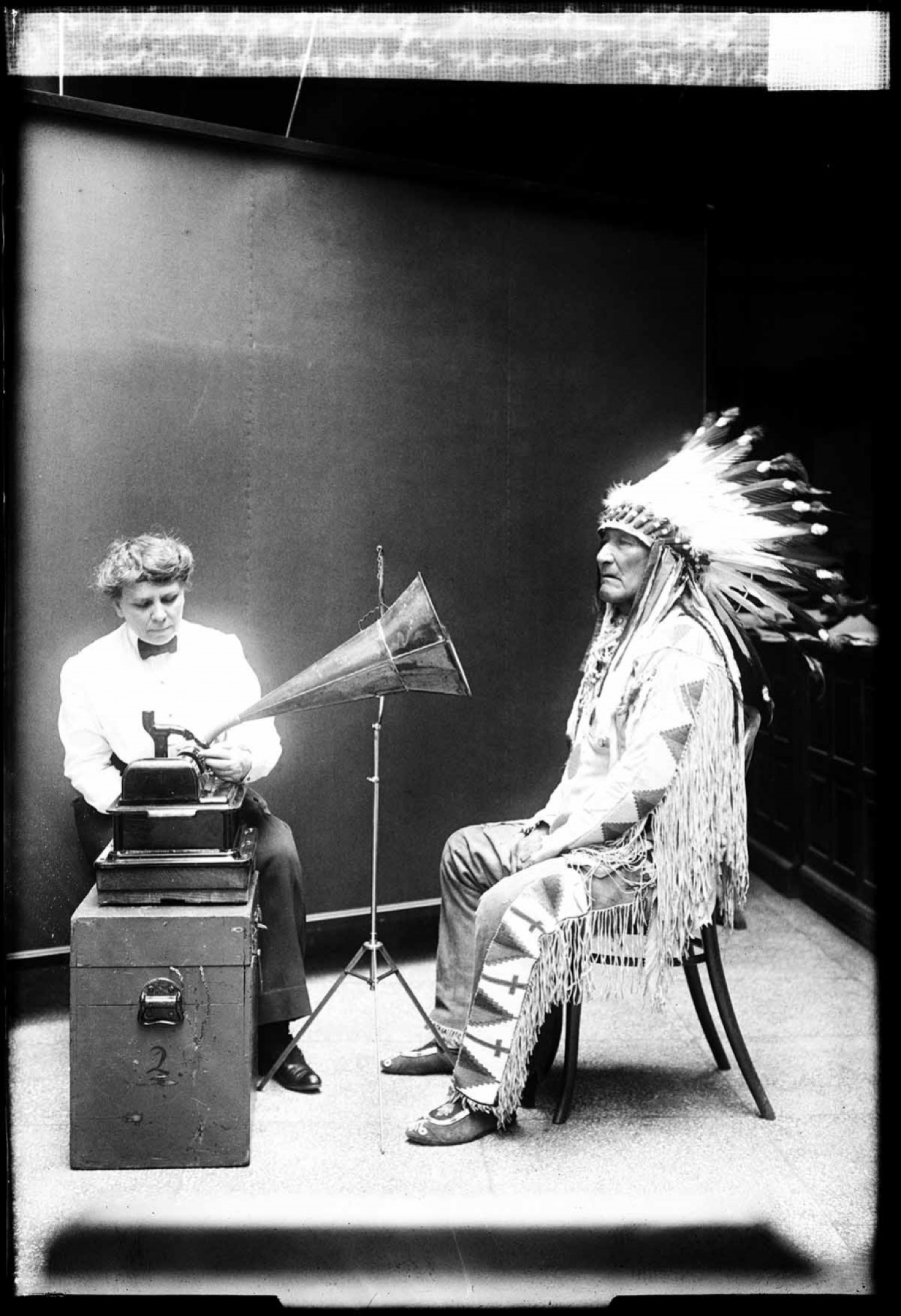

Blackfoot Chief, Mountain Chief making phonographic record at Smithsonian, February 9, 1916. Courtesy of Library of Congress

Eavesdropping on History

By Cynthia Shearer

By all accounts, young Bill Owens was a natural song-catcher, trawling across Texas in the 1930s, the golden era of American field recording. Hayseed and handsome, he had an excellent ear, a big heart, and no hesitation about being the only Anglo in a room. He could hear a black man beating time with a broom on a wall in East Texas and trace that beat back to Congo Square. He was known to stop his car on the side of the road to clip cactus needles to use with his secondhand Vibromaster, obsolete the day he bought it.

Old grannies with Scots-Irish names were dying off, taking their Child ballads with them. Certain phrases lit up in Owens’s ear—gloves of Spanish leather—like colored tracers, back to America’s old insurrections. Deacons in black churches were laying aside old slave spirituals or embellishing them with Chicago jump blues or Hawaiian lap steel. In those days you could still find Mexican Americans singing corridos about Pancho Villa in the alleys near the Alamo in San Antonio. He wanted to understand the whole slow contretemps of Texas history.

History, it turned out, had other plans for him. If you ever find a field recording made by Owens after July 1942, nab it. It’s probably very valuable, since none made after that are known to have survived, and it could also be classified government property.

William A. Owens was born in 1905 in profound poverty on a farm in Pin Hook, a hundred or so miles northeast of Dallas, in a part of Texas already scraped clean of its best topsoil. He learned at an early age that if you listen outside the open windows of black people’s churches, you can eavesdrop on someplace bigger than your white world, hear all the way back to Africa. By the time he was a grad student at SMU in the early 1930s, Owens had the habit of wandering through Deep Ellum or east Dallas’s homeless enclaves at night, listening for the songs of transients and sometimes recording them. The songscape was already being purged of its old folklores by the peregrinations of territory bands like those fronted by Alphonso Trent out of Dallas’s Adolphus Hotel or San Antonio’s Troy Floyd in big venues like the Shadowland Ballroom or the Bagdad Supper Club.

In that decade, you could get the shit kicked out of you by Henry Ford’s goon squads up in Dallas just for talking to a union rep. If you were a Mexican female pecan-sheller in “Santonio,” you could be jailed or run out of town if you tried to organize. Owens frequented churches, pool halls, skating rinks, and front porches—anyplace where folk accustomed to hard work might congregate and make a joyful noise.

By 1941, J. Frank Dobie and Roy Bedichek got Owens on the payroll of the University of Texas and got him some better equipment with instructions to go into Texas communities and create a net of contacts, then seine for songs. John Lomax, the legendary Texas field collector, had by then scoured the South for the Library of Congress and propelled an overall-clad Leadbelly from a Texas prison into the elegant salons of New York progressives. Bedichek offered to introduce Owens to Lomax, but Owens chose to work solo, perhaps intimidated by Lomax’s cigar, or his car outfitted with the latest recording equipment, or his Carnegie and Rockefeller grants. Throughout the next year, Owens recorded more than 200 songs, some in small Texas towns like Corsicana, Seguin, Crockett, China, and Crystal City. Though Owens did no field recordings with the Library of Congress, there are a few hundred at Texas A&M and at the University of Texas, along with some worn-down cactus needles. John Wheat, a digital archivist and translator at UT’s Briscoe Center for American History, probably knows more about Owens’s field recordings than anyone else in America; he says Owens tapped into the deep vein of the other subterranean sweet Texas crude, what Greil Marcus has called “the old, weird America.” Meanwhile, Owens’s recordings await discovery and re-mastering by a new generation.

As a field recorder, Bill Owens enjoyed diplomatic immunity from the racist reprisals East Texas was known to visit upon white “race-mixers.” He got away with acts that got white men murdered in other contexts. He broke bread with black people in their homes, rode around with them in cars looking for songs, took communion with them in their churches. In one East Texas African-American church, he looked out the window during the singing and saw a white man on horseback, listening intently. Owens divined that the man owned the land on which the church stood and had editorial control over the black preacher’s sermons, a ghostly survival of slave times Owens had not reckoned on. The raw power and authority of the black voices Owens captured—the Salvation Singers, the Uplifted Four, the Silsbee Four, and the Benson Quartet—are testament to the trust they placed in him. He had tact; he had discretion.

One time Roy Bedichek sent Owens to a notoriously brutal state prison in Sugar Land, but he returned early, empty-handed. He phoned Bedichek in the middle of the night back in Austin, repulsed by the moral torsion it would have required to solicit songs from black men while white men on horses held shotguns on them. It was the kind of task Lomax could do without flinching. “To a collector,” Owens wrote years later, “people must be more important than their folklore.”

Border Spanish gave Owens difficulty; his own native tongue was East Texas whang. John Wheat tells the story of how Owens crossed to Matamoros once with a young Brownsville reporter, Américo Paredes, future father of Mexican-American folklore, acting as sherpa. In a bar where Owens was the only Anglo present not long after some political “oil friction” between the U.S. and Mexico, Paredes “read the room” and advised they repair back over the border to Brownsville, where Paredes and his wife—the soon to be famous Chelo Silva—would play him some of the traditional songs the Matamorans were not inclined to give up. The results are rich and rare in their own way. Silva’s sultry bolero-influenced “Cielito Lindo” as recorded by Owens in 1941 is spellbinding, like encountering the voice of Linda Ronstadt years before she was born.

If Owens went out in search of African survivals, he sometimes came back with something more evanescent, such as an aluminum disc of Miss Freddie Lee Kirby of Galveston, an African American singing equally under the influence of the Carter Family as she had undoubtedly heard them on border radio, XERA out of Del Rio. On the recording “Heaven’s Radio,” Kirby croons with crisp Marian Anderson elocution how the Precious Savior eavesdrops on us all:

Canvassing Texas for undocumented songs and sounds, Owens stumbled across the big secret: field recording is holy work, eavesdropping on the unsyndicated histories of the world. In 1938, he had witnessed Czechs singing their national anthem, “Where Is My Home?,” in Texas dance halls as Hitler’s tanks were rumbling in to Bohemia and Moravia. In March 1941, he found a black bluesman named Roosevelt “Gray Ghost” Williams in a Navasota skating rink singing “Hitler’s Blues,” and got him written up in Time magazine. On the King Ranch in San Perlita, Owens learned how to authenticate a corrido by listening for the despidida, the last stanza where the originator of the ballad leaves his signature, handed down for generations by some who could read neither music nor language. He spent May of 1941 covering San Antonio, lovely old arsenal of a city he knew like the back of his hand. Among songs he caught there was “Chinese Refugee Song,” a quiet lament “in foreign tongue, presumably a dialect of Chinese,” from a pretty young woman named Toy May. Bedichek left us one of the better portraits of Bill Owens when he wrote to him once that he thought it was a spiritual thing, watching him work in Odessa, spontaneously dancing with his subjects: “You seemed a kind of incarnation of Pan, not wicked, or willful, but in fun-loving mood, and not in lust, but more as a mere joke, ‘ready to twitch the nymph’s last garment off.’”

The final Bill Owens recording in any public collection is from early 1942, of a fiddler down in Carrizo Springs. By then Owens had acquired the habit of haunting the railway stations, watching the soldiers come and go. That was the beginning of the end of his civilian field recordings. He joined the army on June 25, 1942, in San Antonio. He was 5'6", 169 pounds, in possession of a Ph.D., and fearless in the face of substandard recording circumstances. His other asset was a solid network among the poor, the downtrodden, and the discontent, spanning all of Texas and reaching into Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. As America’s involvement in the war was escalating, Owens didn’t get sent overseas; he got sent to Chicago and then to Tulsa. For the rest of his life, he maintained a gentleman’s silence about his required participation in what amounted to a domestic surveillance program conducted against U.S. citizens on American soil. The army trained him as “Special Agent 2142” in the Counter Intelligence Corps, assigned him to the “Zone of the Interior.” Agents were issued handguns and given a clothing allowance so they could blend in with the civilians they were tasked with investigating, and forbidden thereafter to speak about their duties. Owens chose a blue suit, white shirt, black shoes.

Among the Bill Owens papers at Texas A&M are some army intelligence training manuals, with his handwritten note from years later explaining they “are still useful.” The syllabus at the Chicago site was grafted from an old FBI training manual. CIC recruits were trained in basic gumshoe investigative technique, shadowing, lock-picking, evidence collection, and how to “supervise” a telephone with a homemade headset. Agents completed mimeographed worksheets on hypothetical characters with names like “Willie Wildlife.” They were given remarkably realistic dossiers of paperwork on hypothetical scenarios: investigate a scientist, a civilian, each other. Suppose John Doe is a wonderful aircraft worker, but your informants tell you that he likes boys and listens to opera, the manual proposes. What then? “The purpose of the report is to ascertain the LOYALTY, DISCRETION, INTEGRITY, AND CHARACTER of the person under investigation.” What’s the subject’s name? Aliases? Education level? Work? Salary? Bank? Credit? Wife? Children? Any strange sexual proclivities?

Agents were ordered to build and exploit a network of informants, especially with hotel doormen, bellboys, house detectives, housekeepers, barbers, and waiters, but also with taxi drivers, store owners, credit men, automobile dealers, the neighbors, and the neighbors’ kids, as well as “persons who, if not criminals themselves, are close associates of criminals, and who live in close proximity to the underworld.”

The school’s commandant who compiled the manual was a Mississippian named Garland Williams, a former FBI narcotics agent who would shortly move on to Wild Bill Donovan’s O.S.S. His 1941 instructions on how to “supervise” a telephone offer a glimpse of the scales of the beast, plausible deniability, already rattling its chains in Washington’s basements. The document’s headnote reassures that wiretapping of Americans was at that time illegal, therefore the instruction they were about to receive was in no way to be construed as permission to wiretap. But just so they’d know, the whole procedure would undoubtedly be legal in the foreseeable future and was so minor and simple that “your local radio repair man” could fix you right up with a headset receiver, a condenser, a variable resistance unit, and two wires, some clips. Persons of interest were referred to as “violators.” You served your country by impersonating a phone company employee, or by booking an adjacent hotel room. You listened for disaffection, which the manual clearly defined for them: disloyalty, alienation or want of affection or goodwill toward the U.S. government and those in authority.

To Owens’s ear, it must have sounded like a different kind of heaven’s radio, like Babel Tower itself, the fugue of accents among agents in training, recruited from all over, learning to listen in. From 1942 to 1943, CIC agents investigated munitions workers, secretaries, labor unions, preachers, Japanese, Germans, and each other. But when the CIC produced an amateurish tape recording of what they claimed was a young communist lover in Eleanor Roosevelt’s boudoir, FDR ordered the domestic spying to stop and that anyone who knew about the matter be dispatched to the front lines immediately. Any records of their domestic surveillance program seem to have passed into the realm of folklore. Some say they were destroyed at FDR’s behest; some say J. Edgar Hoover dipped into these files during the McCarthy era. There is a thirty-volume history of the CIC in the Army’s archives, undisclosed to mere citizens. Members of the Texas Folklore Society, who knew him as the precocious song-catcher, will tell you, “The Army sent Bill Owens to Tulsa to watch the black churches.” If there are field recordings associated with this activity, they apparently disappeared into the Defense Department’s massive files of things they would prefer we not know about.

In 1989, Owens published Eye Deep in Hell: A Memoir of the Liberation of the Philippines. He uses the word disaffection several times in this book, but applies it mostly to himself. The book makes no mention of his time in Tulsa, and begins with him sitting (in his plainclothes blue suit, we presume) in the San Francisco Public Library, reading to prepare, before embarking to the Pacific. By May of 1944, he was living with other CIC colleagues in Brisbane, Australia, in an old three-story sandstone hilltop villa known as the Palma Rosa. It overlooked a racetrack. The army apparently used Owens and his field-collecting skills to debrief POWs from the Pacific theater and document war crimes, and his fieldwork was subsumed into the massive web of intelligence reports shared with allies and later introduced as evidence by the International Military Tribunal of the Far East.

By then Owens was observing his own disaffection, not for his country, but for the Army itself. When the Japanese were driven out of the Philippines in 1944, Owens looked around at the Heinz 57 varieties of ambitious insurrectos with names like Aquino and Marcos, and wondered if perhaps Manifest Destiny had been a really bad idea from the get-go. He won the Legion of Merit medal when he persuaded a group of Hukbalahap tribesmen to stop routinely murdering American convoy drivers. All the while, Owens comforted himself with an East Texas homily: “They can kill me, but they sho’ God cain’t eat me.”

These CIC agents did very well when they came back home, over 4,300 men trained by their country to function slightly outside the constraints of the U.S. Constitution. They fanned out across America into its insurance companies, trucking firms, food corporations, oil conglomerates, law and accounting firms, law enforcement and intelligence agencies, and universities. They separated from the army but not necessarily from each other. Their names sometimes surfaced later in the New York Times as they claimed excellent jobs and brides. Owens was one of these excellent men.

Former Special Agent 2142 became a professor in the School of General Studies at Columbia. He settled into a leather-elbow-patch, kids-in-the-Kent-School kind of life, commuting into the city from Nyack. Owens was an Adlai Stevenson liberal, like his colleagues Allan Nevins, Dumas Malone, Richard Hofstadter, Peter Gay, Reinhold Niebuhr. In 1953, he published Black Mutiny, an analysis of the Amistad slave revolt, which Steven Spielberg would later mine for his film. In 1954, same year as the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, Owens published a novel, Walking on Borrowed Land, titled after a Negro spiritual. It got good reviews. His publisher openly cited his wartime experience to market the book, the publicity materials attributing Owens’s authority to the fact that he had studied “friction between the races” during the war. The New York Times reviewer wrote, “He was stationed in Tulsa at the time of an outburst of racial hatred, and there he saw first-hand the problems that are portrayed so convincingly.”

The only domestic insurrection that Bill Owens ever observed on American soil occurred at Columbia University, April 1968, when he was sixty-two years old and dean of the summer session. A student named Mark Rudd led the Students for a Democratic Society in a campus revolt, hard on the heels of urban riots after the Martin Luther King assassination. In their manifesto “Who Rules Columbia?” the SDS demanded that the school wean itself from CIA money and research funded by the military-industrial complex. They specifically called out Owens’s old CIC friend Dana S. Creel, longtime employee of the Rockefeller family.

The Columbia administration was caught somewhat flat-footed, though they had enough advance intel to know to remove a million-dollar Rembrandt from President Kirk’s office before it was “occupied” by students. Dotson Rader, Rudd’s SDS colleague, and one of Owens’s creative writing students, remembered him this way: “Dean Owens played a pivotal if unpublicized role in the events of 1968—his office became the administration’s ‘command center’ after the students evicted President Kirk from his office on the floor above.”

Rudd today will tell you he never heard of Bill Owens, but he remembers the music, how it boosted their morale when the Grateful Dead played for the students, to take a moral stand with them. Alan Senauke, now an abbot at the Berkeley Zen Center, remembers the New Lost City Ramblers, human encyclopedias of almost every folk song ever uttered on American soil. Their repertoire included Child ballads, French chansons, chain-gang songs, sea chanteys, Mississippi levee moans, coal-miner laments, all the old perennial grievances spilling forth from the amps at Columbia, disaffection for government.

Surely it must have humbled Owens and reminded him that time is a tantric thing, to witness that river of Americana pouring forth. America’s big insurrection had issued from the suburbs, from the sons of the excellent men who had come home from the previous wars. Maybe it was a spiritual thing to Owens, to see Columbia boys dancing like Pan, ready to twitch the garments off the nymphs of Barnard or Wellesley, clad in counterculture clothes that resembled the get-up Lomax had Leadbelly wear in a 1935 newsreel for The March of Time, blue denim overalls and red bandanna. If Owens still had his excellent ear, the Ramblers must have sounded like heaven’s radio to him. If he still had his excellent Texas heart, he probably understood the insurrectos more than he could show. Disaffection for your government is sometimes how you show love of your country.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.