McElwee's Confessions

By William Giraldi

A meditation on the possibility of autobiographical art in America during an era of social media narcissism

Certain works of art have an occult way of finding us when we are most in need of them, of their example and wisdom and wit. One night recently I was considering ways to wiggle out of having to write a memoir, which I had insensibly signed a contract to do, and was moving alps of books from one corner of my library to another. There, atop a shelf, reemerged a gift from a friend in the South: not a book, but a DVD collection of the films of Ross McElwee, the North Carolina documentarian whose far-famed Sherman’s March is a charismatic masterwork of autobiographical filmmaking.

I was staggered by the mainlined purity of McElwee’s filmmaking: no cloying measures or intent to dazzle, no sensationalism or emotion in extremis. Extremity is always simple; nuance is hard, and McElwee’s films are paragons of nuance. To spend time inside his filmic cosmos is to become enlarged by a singular chronicle of modern selfhood, of the self in search of its own coordinates, its own particular pitch of being in a world that lurches between the malignant and the divine.

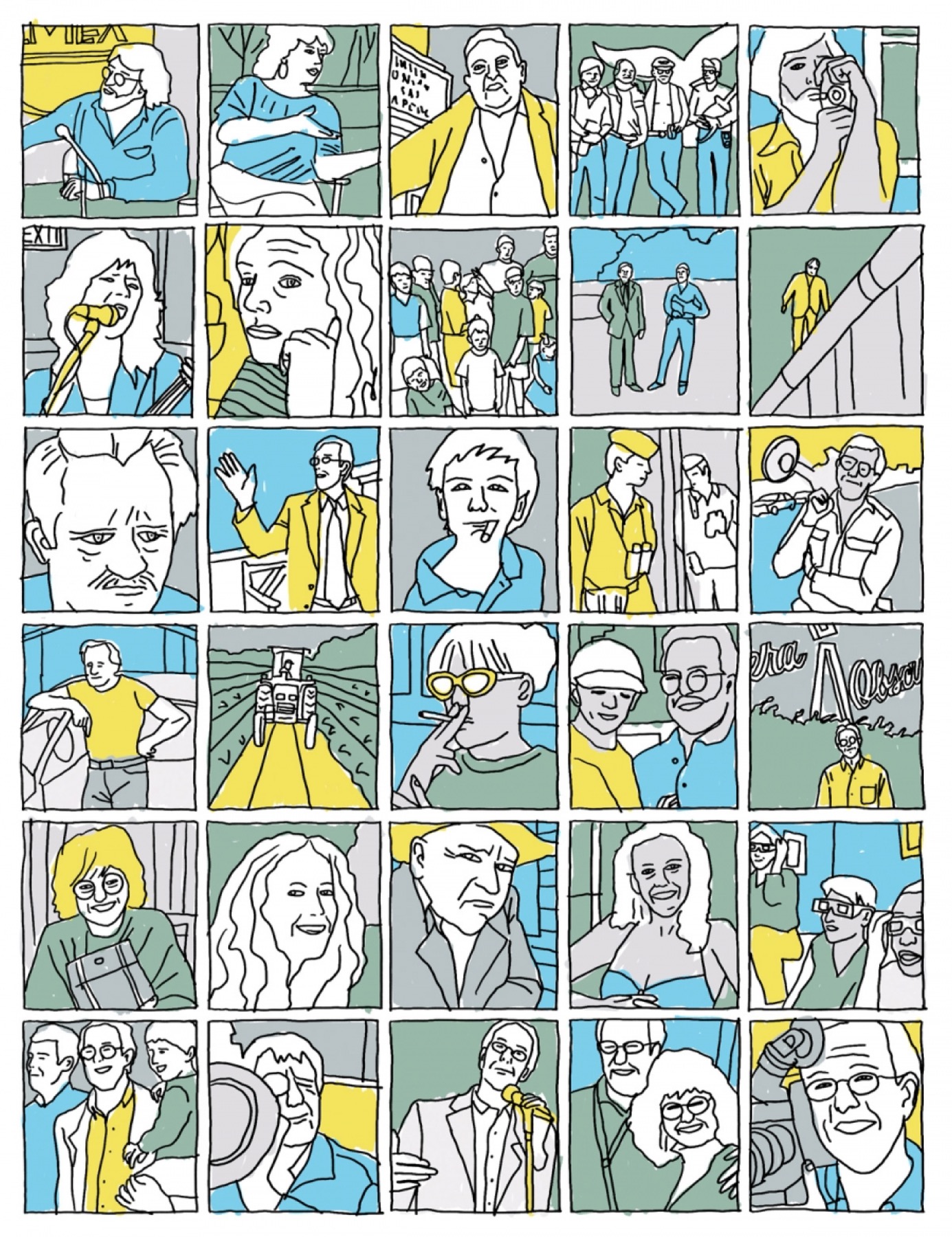

McElwee’s subject is the oldest one, the messy one, the eternal one—his own family and the family’s collisions with and gratings against the wider world. Backyard (1984), Sherman’s March (1986), Time Indefinite (1993), Six O’Clock News (1997), Bright Leaves (2003), Photographic Memory (2011): his autobiographical investigations pulse with a profound subtlety, with a reverberant charm that is both erudite and unpretentious. What other filmmaker has embarked on such a ceaseless expedition of self-awareness? Who has made of himself such a willing pilgrim to disconcerting truths? Allan Gurganus has written of his fellow North Carolinian: “No one else’s body of work feels so unified, human, freckled, questing. No one else’s documentaries know how to tell tales as difficult and true as they are richly funny.”

In one of his finest poems, Theodore Roethke wrote that “a man goes far to find out what he is.” McElwee has lived and worked in Boston since the late 1970s, and you’d think that returning to North Carolina to film his own family wouldn’t have been too far to go to find out, to be reacquainted with what he is—I’m helpless to remember that John Updike’s story collection about the ruination of a family is titled Too Far to Go—but it’s very far indeed when you’ve delved as deep into the familial morass as McElwee has.

Backyard looks at his brother Tom as he prepares to depart Charlotte for medical school, and also at the dignities of the black domestic help employed by his family—it’s filmed almost entirely in the backyard of his boyhood home. Sherman’s March attempts again and again to focus on General Sherman’s incineration of the South, but the film keeps veering into a self-portrait of an intelligent klutz baffled by romance, McElwee’s ode to American restlessness. Time Indefinite begins as a marriage film, a coda of romantic success to wed to Sherman’s March, but quickly becomes his memento mori film after the deaths of his father, his grandmother, and his unborn child. Six O’Clock News takes to the road to immerse itself in a handful of personal stories which, through the toxic acts of God or man, have appeared on the nightly news—it’s a macabre meditation on the random dangers of the “real world” versus the new diapers-and-bottles domesticity of McElwee’s homestead. In Bright Leaves, McElwee parses not only his tobacco baron great-grandfather and the legendary dispute he had with the Duke family, but also the inevitable artistic agon between the fictions and the facts. Photographic Memory revisits St.-Quay-Portrieux, where McElwee attempts to find the sprite of his younger self—when he was twenty-four he worked in St.-Quay as an assistant for an eccentric French photographer—while also struggling to comprehend the maddening intransigence of his twenty-year-old son, a young man blitzed by cyberspace and his own sense of anomie.

If McElwee’s output can constitute a single movement, an elongated cinematic memoir, then these six films constitute his cadenza. Here is an autobiographer offering some direction about how one could go about presenting to the world one’s ostensibly quotidian life. In his essay “The Knife in the Brain,” McElwee writes that “autobiography is where DNA’s double helix gets bent and twisted, turns in on itself, tangles and knots its strands, and yields its greatest challenge to the writer.”

Maniacally descriptive, Updike yearned in his work to “give the mundane its beautiful due,” and McElwee does exactly that in what he’s called his “home movies”—unscripted and mostly spontaneous in the truest sense of cinema verité, ruminative in pursuit of meaning but always conversational in that irresistible Southern way. For McElwee, personality is style, and style, as Nabokov taught us, is matter. What in lesser hands would seem a fetishizing or exploitation of ordinary existence, an adolescent indulging in the many storms and quirks of personality, becomes in McElwee’s films a lasting revelation of the necessities and contingencies of selfhood.

To be modern is nothing if not to be individual. For all of Augustine’s probing of the self it’s striking how little individuality you’ll find in Confessions. Modernity owes a tremendous debt to Romanticism, because one of the chief differences between the classical and the Romantic is the conception of self, of how individuality perforce leads to individualism. McElwee’s work is heir to Romanticism not only in its unabashed alloy of thinking and feeling, but in its understanding that the ineffable self will seek its own sound—it understands that the self has agency in the world, that the self is a mover and not merely a thing moved upon. McElwee, Gurganus maintains, is “our own updated Don Quixote” whose investigations into selfhood are constantly “teaching, leading, teasing, testing us.” A Ross McElwee film is outright impossible to mistake for any other.

McElwee’s ancestors settled in the foothills of North Carolina in the 1700s. In Bright Leaves, McElwee admits: “North Carolina still seems, in a kind of understated way, like the most beautiful place in the world to me.” Gurganus writes that McElwee “embodies our state’s proudly professed modesty, our love of tribe, our abiding connection with the land itself as our literal history.” He was born in Charlotte in 1947 and brought up in a family of doctors: his father, his grandfather, his brother, and a mélange of relatives. One uncle was a camera aficionado they named “Super-8 Nate.”

He left Charlotte in 1966 for Brown University, where he studied literature under the anarchic fiction writer John Hawkes. His plan was to become a novelist but he was compelled and then seduced by photography and film. After Brown he returned to Charlotte and was hired as an in-studio cameraman for a local TV station, WSOC. This proved dull and dulling, and after a year he enrolled in a three-week filmmaking seminar at Stanford, where he worked in Super-8. He intended to remain in California, the logical terminus for any inspired soul with a movie camera, but a friend phoned to tell him about a job offer at a television program in Washington, D.C. The program? Bill Moyers Journal on PBS. The position? Loading camera magazines with 16mm film stock as fast as the cameraman could shoot them. He took it.

Soon he’d read about a new graduate film program beginning at MIT, one that would star two filmmakers he’d admired while at Brown: the socio-political and personal documentarian Ed Pincus and the cinema verité pioneer Richard Leacock. McElwee showed up at MIT, an eager young man full of frisson, and interviewed with Leacock and Pincus. They took him. He began Backyard during his time there. After graduation he worked as an editor for the science program Nova, at WGBH, the PBS affiliate in Boston: another occupation of spirit-quashing banality. He quit to finish Backyard, and Backyard prepared him to make Sherman’s March, and the rest is, as the sayers say, history—although future is more like it, because in the aesthetic, narrative, and box-office success of Sherman’s March, McElwee had earned his future.

He’s been teaching filmmaking at Harvard since 1986. His office is a relaxed and carpeted bunker in the basement of Sever Hall, at the campus hub in Harvard Yard, and on the day we met to converse about autobiography, an Old Testament rain whipped at the windows. He has the kind of mien that makes you want to take him in and feed him a bowl of soup. As anyone can see from his films, he’s impeccably kind and courteous with the slightest tincture of vulnerability. His voice is just slightly more than a whisper, a medicinal sound that has retained its Southern lilts, although it’s true that decades in Boston have thieved from the auditory prominence of North Carolina.

It’s tricky to meet someone about whom you already know almost everything. More than once I had to scold myself into remembering that the intimacy I felt was not an intimacy born of personal experience but, rather, a kind of intimate abracadabra occasioned by his art. This is testament to his consummate skill as an autobiographer: he permits you to know him, chaperones you into his life, as few are willing to do.

On his desk sat three large monitors on which he does his film editing—“Where the magic happens,” I suggested, and he said, “It doesn’t feel like magic when it’s happening. Magic is supposed to be nice and quick. Editing takes me forever.” Surrounding us on shelves were everything you’d expect from an archivist—“my attempt to deal with the chaos of being an independent filmmaker”: mini DV cassettes, now obsolete; DVCAM cassettes he once used for teaching purposes (now, of course, he and his students use memory cards); Beta copies of 16mm film (Beta was stabler than 16mm); his completed films on DVCAM, on VHS, on Beta and Beta SP, on DVD; written logs of everything he’s shot in order to locate images on film; detailed production notes in binders; scrapbooks relating to his films and film festivals. This cave-like space gave off the distinct aura of having witnessed the completion of important work. McElwee has spent half of his life holding a microphone in the direction of other people’s mouths, and he showed no annoyance that for three hours I held one in the direction of his.

The conflict I’m having, Ross, with autobiography and my own forays into memoir, is a conflict I’ve articulated to myself as one between expression and assertion. I’ve stolen this formula from G. K. Chesterton, who used it to damn the poetry of Swinburne. Expressing yourself is simple: any personal experience or impulsivity will do. Go holler in the street. Asserting yourself, however, is another matter. I mean assertion is expression augmented by or filtered through deep consideration of the conundrums of selfhood, and not just a promiscuous emotional romp through one’s own past or through one’s own feelings. This is what I’m seeing in so many contemporary American memoirs: lots of emotional expression, not a lot of artistic assertion.

“I like your idea that there’s a mistaken identity going on in autobiographical storytelling that confuses expression with what you call assertion, but that I would word as reflection. That’s interesting because the kind of filmmaking I do combines those two things. In other words, to film the way I film, which is pretty impulsive and spontaneous, could be likened to the kind of writing without thinking that you’re talking about. I’m responding in the best sense of cinema verité to what’s happening in front of me—I’m not trying to direct it or control it, not doing multiple takes. That’s the equivalent of an impulsive response to what’s happening around me. But then, for me, it always seemed vital to add the voiceover, to give that filtering process you speak of. That narration in the voiceover is highly considered and worked on, wrought, over a long period of time. The hardest part of making my films is not the shooting of them, which is pleasurable for me, but writing the damn narrations. The transcripts of my narrations are probably only thirty pages, but it takes me months, months, to get it the way I need it to be. It’s no different from what you do, in that sense. The juxtaposition of those two things, the impulsivity in filming and then the deep consideration in editing, their marriage, creates something different from the kind of unconsidered expression we’re seeing in so much contemporary memoir.”

People now have access to their pasts in a way that’s unprecedented in human history—it’s possible for people to have their entire lives available to them on video and in photos. Combine that with the current belief that anyone can become a writer, with the proliferation of MFA writing programs and writing workshops, and with the ease of online publishing, and you have our current avalanche of autobiography. And in terms of filmmaking—we’re all filmmakers now because we all carry around movie cameras in our pockets.

“Yes, in terms of media, of the arts, of memoir, the fact that there’s now an inexhaustible supply of the record of the past for people to access is going to make it very, very difficult for artists to produce interesting work. And I think this is what you yourself are finding when you say that so much American memoir has become defiled by a kind of promiscuity with one’s own past: the culture as a whole has a tendency to self-examine and to think about one’s own life, in terms of context or social reality or whatever, and it’s being done no matter how superficial that examination may be. And when you marry that with the media that’s now available to those kinds of people, then you have an onslaught of autobiographical filmmaking and memoir publishing. But I think, also, that it will run its course. It has to. There’s a resistance to it, frankly. I know that from film festivals—there’s less fascination than there was a decade ago with that tendency to turn a camera on your own life. When I did Sherman’s March in the mid-1980s it was a truly bizarre thing to do, to roam around with a camera to record the things that were happening to you.”

I empathize with that compunction to take out the phone and film everything the kids are up to. I’ve got to fight myself to keep the damn thing in my pocket, to be a part of what my kids are experiencing rather than just a passive documenter of it. I remember what you said in an interview you gave ten years ago, how “horrifying” it was that all these parents are obsessively recording their kids.

“I was probably being dramatic when I said horrifying, but let me give you an example of what I meant. Here at Harvard there are nonstop tour buses. I saw a guy yesterday with a cell phone camera, striding along, recording everything as he walked. It was as if he didn’t have the time or the interest even to consider Widener Library or the chapel now as architectural presences, but maybe he’d catch up with them later on his cell phone. He was by himself, too, that was the strange thing: striding along, shooting this, shooting that, in a hurry to get to the next attraction that he also won’t fully see or appreciate. And I thought about that afterwards: what does it mean that he’s recording these images now, expecting to look at them later? What will they mean when he looks at them later? Will he think: I recorded that, good, now I don’t have to think about it, or will it occur to him, Wow, I was actually there and I didn’t take it in, didn’t sense that I was in this centuries-old important location. He was too busy recording to actually respond to or feel what he was seeing. That must happen a billion times a day, people recording images with no purpose, assuming that later they might want to look at them and reflect on them, but of course they never do because they’re too busy recording other images. It’s a real conundrum, much more so than when I gave that interview in 2004.”

Because there was no real social media then, not the kind of online rabidity we see today?

“Exactly, yes. There was no YouTube at that time, nor had Facebook really taken off. This current social media networking has had an immense effect on what we think of as autobiography and nonfiction filmmaking. I talk about this a lot with my filmmaking students, this suspicion of media, of filming, of the idea that anything that is being filmed can end up on YouTube and potentially be viewed by one half of the earth’s population. That’s a huge consideration, and one of course that didn’t exist at all when I was filming Sherman’s March. Of course the other thing that has caused a change in the culture’s reaction to autobiography and nonfiction filmmaking is reality television, in which we have hundreds of shows that supposedly show us people in their real lives dealing with some version of a real-life challenge. They have affected the way most of the population thinks about documentaries, what it means to become involved in nonfiction filmmaking, even if it’s not autobiographical. All of this has complicated the picture immensely. On the other end, as you said earlier, what’s different now from when I began is that everything’s been democratized, access to camera and editing equipment: anyone can make a movie now. That part of it can be terrific, I suppose, but it does make everything much more complicated, especially when you’re teaching younger people how to make documentary.”

But how has your own aesthetic, your own idiopathic vision been altered by all that? I would think that it must have had a catastrophic effect.

“No, I don’t think so, although maybe it should be having a catastrophic effect. The one effect that I can quantify is that my films are getting shorter because the culture’s attention span has shrunk. Sherman’s March is two hours and forty minutes, and Photographic Memory is only eighty minutes. That’s half. But I still indulge in the long shot, the unedited sequence in which people can start sentences over again when they’re explaining something, or those shots in which nothing much happens. All of those traits I developed as a documentarian thirty years ago I’m still practicing now. I still believe in them. Maybe I’m a dinosaur, but I’ll continue to use that kind of filmmaking technique in my work, no matter how attention deficient the culture becomes—even though I’d be lying if I said that it wouldn’t matter to me if no one saw my films, if no one responded. I can tell you that I’m not calculating, not trying to achieve certain effects in an audience when I put a film together. I’m composing from some flawed place within me, that source of inspiration and aspiration, hoping to make connections with someone out there.”

I’m not the first to notice the essayistic quality of McElwee’s films—one admiring scholar likens him to Montaigne, and while that might appear a trifle hyperbolic, surrender to the almost desultory pace and the narrative pitch of a McElwee film and you’ll begin to see the sense of that comparison. Aldous Huxley conjured a great phrase about Montaigne’s method, “free association artistically controlled,” and G. K. Chesterton once commented that the essay, as invented by Montaigne, was the only literary genre whose very name suggests “a leap in the dark.” Watching a McElwee film you have the distinct sensation of that leap, of a thrilling aimlessness through that dark. As in your own life, anything can happen—you’re never completely sure how one predicament will morph into the next. William Rothman has written: “That he finds his stories by filming his life as he lives it is part of the story a McElwee film tells.”

McElwee shares with Montaigne the conviction that one’s life gains fuller meaning only outside the confines of the personal and parochial, only through more ecumenical concerns, a dialogue with the pressing issues of one’s world. Take this boast by Terence, “Nothing human is alien to me,” and add it to this advice from E. B. White, “Don’t write about Man, write about a man,” and you have what must become the artist’s credo for creation. That’s what elevates a McElwee film onto the honored peak of art: the climate of his mind as it tempers the weather of his emotions, and his interest in the varieties and vagaries of humanity. (In addition to his autobiographical films, he’s co-directed features about people living among the rockets-and-moon madness of Cape Canaveral and a community that dwells in a curious limbo along the Berlin Wall.)

McElwee has taken Montaigne’s admonition “I propose an unimportant life without luster” and shown precisely how the lusterless can gain importance when the life is shifted, twisted into the proper light. McElwee as a filmmaker is literary in every sense of the term, since he crafts his extensive voiceovers and since his films wouldn’t function without them. His voiceovers have the knowing glare of literature—Gurganus writes that McElwee’s “voiceover persona is always that of The Little Fellow blessed with Chaplin’s investigative energy leading to Keaton’s fall-guy grace”—and it’s not surprising to learn that there was a time when McElwee considered becoming a novelist. The opening voiceover of Backyard is a lustrous example of the conversational and comedic tenor McElwee employs in his narrations:

Perhaps because he’s both an essayistic and rogue filmmaker, McElwee often doesn’t get credit enough for the manner in which his lovely eye apprehends, and especially the way it can apprehend nature. Wordsworth, you will not be shocked to learn, had a paramount influence on McElwee in college. Bright Leaves begins with a beautiful shot of tobacco plants breathing hotly in a field. In Photographic Memory there are lovely considerations of the St.-Quay coast, waves flopping onto shore, sandy paths cutting through tall grass. In Backyard, we hear hidden dogs barking behind an almost surreal scrim of shadows and sun-stroked flora. And halfway through In Paraguay—McElwee’s unreleased 2008 film about the adoption of his daughter—there’s an astonishing long shot of the shadows of tree limbs and leaves swaying, brushing against a stucco wall before a man enters the frame and departs on a scooter. That unknown Paraguayan man is key to the shot—where has he come from? where is he going?—because he saves the image from approaching a sentimental fixation on the splendor of nature.

Writing in the New York Times, Mike Hale suggested that McElwee leans toward “self-indulgent philosophizing,” a suggestion that performs the trick of being simultaneously wrong and redundant—what philosophizing doesn’t contain some element of self-indulgence? Sustained thought, by definition, requires the self to indulge in its own mind and motives, its own undulations as they relate both to others and to the unseen. Marian Keane, writing of a specific shot in Bright Leaves, a shot in which McElwee films himself on a park bench, observes that “he shows us himself thinking . . . he gives us an image of thinking”—Ross McElwee as Auguste Rodin in a medium less adamantine but no less imperishable. So part of McElwee’s mission might be “how to make sense of the data one gathers from what appears to be a metaphysically senseless world,” as he wrote in his essay on Walker Percy, but that probing into metaphysical problems does not ipso facto equate to self-indulgence in the pejorative sense in which Hale meant it: as the straightest avenue to narcissism.

The Delphic injunction “know thyself” has become for McElwee indistinguishable from “film thyself,” and yet the key to his autobiographical films is that they are mostly about other people. A. O. Scott’s assessment of Sherman’s March as the “founding document of narci-cinema” is a faux-pithy quip of error. Marian Keane has pointed out that McElwee’s work “is no more narcissistic than Leaves of Grass,” and I wish to second that contention. Think of narcissism as self-obsession stuck to egomania and vacant of any sincere concern for others: for true narcissists, other people have no reachable reality in either the actual or the abstract. McElwee, on the other hand, is so virtuous, and so committed to both actual human lives and their abstract implications, that his own life and art would be inconceivable without the welcomed participation of others.

In Photographic Memory, there’s a compelling shot of McElwee’s son, Adrian, in a café, on his computer at the window, and you can see McElwee’s reflection in the window outside, Adrian’s face superimposed where his father’s is behind the camera—the melding of identities, the fusing of selfhoods in assertion of continuity and love. No truly self-indulgent artist is capable of such an image. McElwee’s films are tremendously tender toward others, and tenderness is always an indication of probity and obeisance. That might be an apt description of his autobiographical project: an artist attempting to maintain his probity and obeisance while trying not to be outwitted and outdone, trumped by the troublous stipulations of living.

Consider his refusal to pass judgment, to interfere with our own verdict on his subjects. In Bright Leaves, there’s a tobacconist whose mother died from an ironclad smoking habit. We hear her epic idiocy when she claims that her growing of tobacco has nothing to do with her mother’s death, “nothing to do with anyone who dies,” and McElwee cuts away at once, leaving us with the reverberation of that self-padding stupidity. He understands that her own sentences are more damning than anything the camera or his voiceover could give us. Or in Sherman’s March, when he’s too much of a gentleman to criticize three fantastically doltish women with whom he pursues romantic possibilities—one who believes she’s a prophetess who can get Burt Reynolds to fall in love with her; one who believes in millennial hocus-pocus and keeps company with gun-toting survivalists; and one whose nutty Mormonism requires her to deny the life-enhancing pleasures of coffee and alcohol and also to stockpile nonperishables in preparation for the coming apocalypse. McElwee once said in an interview, “I try as best I can not to present people as being ridiculous,” and yet you can almost see his camera cringing in the face of so much unreason.

In Six O’Clock News there’s just a few seconds of veiled criticism in the voiceover, after an old couple, whose home was spared by a tornado, tells McElwee that God directs their fates—that God directs the vanquishing paths of twisters. McElwee wonders if life is easier if you believe God is in control, or easier only if your home has been spared. In other words: let us ponder the fatuity and smug presumptuousness of claiming, as you stand there unscathed, that the Lord knew what he was doing when he ravished those other lives but left yours untouched. In that same film, McElwee connects with Steve Im, a Korean immigrant whose wife was grotesquely murdered in a robbery. “Out of control this world,” Im says. “God cannot control this world.”

And that’s the other ingredient that contributes to the roiling dynamism of a McElwee film: his unforced cerebrations of spirit. And I don’t mean his own precious spirit—I mean the spirit of us all. An agnostic intellectual, McElwee nevertheless knows that without some engagement with the holy, some overlap of the secular and sacred, a work of art remains stymied in a pupal phase. In an interview with Lawrence Rhu, McElwee admitted that “apocalypse is a common theme that keeps coming up in the films,” and let’s remember his dark-night-of-the-soul insomnia in Sherman’s March, his bad dreams of nuclear hecatomb—the film’s half-serious subtitle is “A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation.” In Paraguay has a stunning scene of a wordless cripple begging on the steps of a church in Asunción, McElwee wondering in the voiceover if faith permits this man his seeming contentment and calm despite his condition. With its eye on the wreckage of this world, on the indiscriminate doling out of woe, Six O’Clock News becomes a film about the agon between faith and fate—“the invisible virus of fate,” McElwee calls it. And then: “I keep finding myself in church with a camera.” Why? Because the pews are where his subjects find some unnameable solace, and he’s earnest enough to follow them there. And that’s the one thing a genuine narcissist can never quite pull off: empathetic earnestness.

Artists are by default a narcissistic set, and I’m loath to add to that reputation by writing a whole book about myself. I also have a strict policy of never disagreeing with Oscar Wilde, who said, “I dislike modern memoirs. They are generally written by people who have either entirely lost their memories, or have never done anything worth remembering.” Wilde also said, “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.” Fiction is the mask that shows the truth, while memoir is normally the bare-faced lie. But watching your films gives me hope for my own enterprise. You’re the reluctant narcissist.

“That’s a useful phrase, reluctant narcissist, and probably an accurate one. And it’s interesting that you raise this issue of narcissism because I grew up having been taught Southern manners, and Southern manners always included the stipulation that you needed to be attuned to other people much more than to yourself. There’s a way in which that can be a superficial trait but there’s also something profound about it, something necessary, at least for me, to make my way in the world. It was a good lesson for me to have been taught. Therefore it’s incredibly ironic that I have ended up making autobiographical films because I don’t feel comfortable talking about myself or dwelling upon my own situations. But the way I’ve dealt with that discomfort is to allow it to be in my films, and I think you have correctly read that strain in me, my reluctance to put myself forward. Another way I save myself from self-obsession is to weave in themes from the world at large. Without those my films might indeed be narcissistic. Sherman’s March takes into consideration a very tragic era in American history and the very real threat of nuclear weapons proliferation. It takes very seriously the notion that it is difficult to establish a meaningful loving relationship in a time fraught with such anxiety, as the Eighties were, and that certainly hasn’t changed much.”

There’s also the self-referential aspect of the film, its playful awareness of itself. I remember you say at one point in the film that it seems you’re filming your life in order to have a life to film. And then you say that your “real life has fallen into the crack” between yourself and your film.

“That’s true, the film also investigates or gives thought to, sometimes humorously but sometimes seriously, what it means to make documentary images as opposed to fictional images, as represented by Burt Reynolds and his making of a Hollywood feature at the same time I was making Sherman’s March. There are some humorous juxtapositions and intersections there that I’m very interested in and have pursued in my subsequent films, this notion of nonfiction versus fiction. How are they different, what are they striving for? So by allowing my films to have these other considerations, other themes, I think I have partially counterbalanced the autobiographical component, and diffused to some degree the danger of narcissism, though not entirely, I know. I think if Photographic Memory has a problem, the thing it doesn’t do as well as the other films is to open its eyes to look around at the world and think about something that’s going on elsewhere.”

To my mind Photographic Memory isn’t marred at all by that lack of ecumenical engagement: I find it a necessary meditation on the quagmire of the parent as agent in the life of his child. Because, you know, Time Indefinite doesn’t have an extensive worldly engagement either.

“It doesn’t, you’re right. But its passion and emotion are so pure, if I may say that, that it carries the film—those primal things that the protagonist/filmmaker was going through at that time. Photographic Memory is special to me, of course, and I appreciate what you say about that film, but I understand some people thinking that it’s perhaps not as broad as the other films in its considerations of the world. The main thing I’m investigating in that film is the passage of time, something Proustian—I went back to France to make a Proustian film. My intersection with my son at that point in his life provided an opportunity for me to think about the profound implications of thirty years having passed by, thirty years since I was his age, and what that means to us as mortals. It’s a significant chunk of one’s life. I think in that sense the film is pure and successful in its goals. The question is always how does an autobiographical artist presume to take in the world’s complexity.”

This passage of time you speak of: it’s something I’m aware of in all your films, and aware of most pointedly in the voiceovers. In Backyard the voiceover is youthful, optimistic, brimmed with curiosity: it retains that wide-eyed wonder of what remains possible, the awe of discovery. The narrating in Sherman’s March is similar, so steady and pleasing in juxtaposition to the hurly-burly often in play around you. I hear that voice begin to shift in Time Indefinite, and by Six O’Clock News your voice has taken on a slightly pained lilt, all the illusions siphoned from it. And the narrating of Photographic Memory is downright despairing to my ear.

“It’s undoubtedly true what you say, although no one has pointed that out to me before, and it’s got to be a result of the fact that as you get older, life in many ways has to become sadder, for all the obvious reasons. My voice’s sadness in Photographic Memory comes from two things: pondering the fact that thirty years have gone by so completely, so quickly, and also my concern about my son’s welfare. Those two things have got to be contributing to what you detect. I think you’re very sensitive about this, this gathering sadness in my narration. But I hope that’s not the preponderant thing that the film conveys because it’s so necessary to have a sense of humor about one’s life and to allow comedy to move into art, to have a place in the film. Without it, we can’t survive. Humor is totally critical to making these kinds of autobiographical films, an agent that helps you devote portions of a film to your own life. Otherwise it’s unfettered narcissism, as you’ve said.”

I should add, too, that your Southern accent has suffered some attrition at the hands of New England. Why didn’t you return to the South after you graduated from MIT?

“Well, I stayed in Boston after MIT because almost immediately I found work as an assistant editor, and then as an editor at WGBH. I augmented this with work as a teaching assistant for a course in filmmaking here at Harvard. I kept thinking I would get back down South after a year or so of WGBH and Harvard, but the contracts and freelance work kept getting extended. As a Southerner, I sometimes think of this as accepting an illicit bribe to stay put in Yankeeland. The other reality is that I tried very hard to find funding for Sherman’s March as a work in progress, and applied to ten arts foundations and PBS affiliates in North and South Carolina. All of them turned me down—and who could blame them? A film like Sherman’s March had never been made before. However, a WGBH-Boston producer named Peter McGhee, who had something of a reputation of taking chances on programming, provided me with funds to get the rest of my footage processed and a print made. He then had the good sense to allow for the film to be distributed theatrically for a year before airing it on PBS. That’s fairly common practice now, but back in the 1980s, it was absolutely forbidden that PBS programming be seen in theaters before airing. Peter and I were sort of inventing a distribution model for independent documentaries in the States, and I don’t think we were even aware that we were doing this. So if I had gone back to the South, Sherman’s March might never have been made.”

In Sherman’s March, McElwee is, in a flawless Saul Bellow phrase, “a phoenix who runs after arsonists”—each romantic possibility is practically engineered to incinerate him, to leave him disappointed and dejected, and yet panting, ready to rise again for another charring. “A sort of creeping psycho-sexual despair begins to overtake me,” he says in the voiceover, after yet another love interest lights out for vistas wider than what McElwee can offer. His diffidence with women, combined with his high regard and unstanchable desire for them, is a stinging cocktail to sip from. When Henri Barbusse, in his 1908 novel L’Enfer, wrote: “It is not a woman I want—it is all women, and I seek for them in those around me, one by one,” he could have been speaking about McElwee in Sherman’s March.

But the film succeeds so resplendently because it manages to be about many things at once, one of which is the inevitability of arrivals and departures (there are two airport scenes), of how we enter periods stage left quite differently from how we exit them stage right. The film is overrun by those writhing on that pivot between desperation and ambition—the Burt Reynolds look-alike who waits hours at a hotel in hope of finding stuntman work; the aspiring thespian who believes her destiny lies in Tinseltown; Ross McElwee himself. In his whiskey-sipping, improvised speech to the camera about General Sherman, late at night in his father’s house, McElwee is dressed as a Confederate soldier (having just come from a costume ball), and twice in this speech he refers to Sherman as “tragic,” his voice shot through with sadness at the possibility that his own life will wrap up just as tragically. McElwee remains aware of Sherman as an ambitious failure, and he remains aware of their similarities, right down to their russet beards.

But this question is waiting: Why the incessant filming of his own life? Why this autobiographical itch? In Sherman’s March, his friend Charleen introduces McElwee to a young woman and he insists on filming the moment. “This is not art!” she scolds. “This is life!” In Sherman’s March, of course, there is little aesthetic distinction between the two. In this, as well, McElwee becomes heir to the Romantics, to the Wordsworth of The Prelude. Neither Wordsworth nor McElwee subscribes to a fatuously idealized conception of his own existence as art in the making, common enough among a certain species of outlaw artist working from a deficit of imagination. For McElwee the autobiographical filmmaker, as for Wordsworth the autobiographical poet, the process of living does not in itself equal art—rather, the exigencies of having lived contain the potential to become art through imaginative assertion. The art/life duet in McElwee results from his contemplative agitations, from his serious thinking about the ways in which an ordinary life accrues significance. This is part of what Gurganus means when he says of McElwee that “no filmmaker working seems more organically aligned with his material.”

Here, too, is what McElwee admits in his essay on Walker Percy: “Events of life around my family’s house were somehow transformed when I saw them through the lens,” and then this bit of antinomy: “The experience of filming both gave me a detached perspective on what I was filming and simultaneously led me to see deeply into the world I was filming.” He makes a similar admission in Time Indefinite, when he films the drawing of his own blood: “If I watch through a lens it seems less real to me.” It’s a matter of apprehension, of course, but the proper apprehension, an apprehension that is both artistic/aesthetic and personal/purgative—the purging of personal devils while the aesthetic embraces the artistic. “I’m camera shy in a reverse way,” he says in Sherman’s March, but what is also reversed is the way in which each shot peers inside him even as the lens remains pointed at others.

In Bright Leaves McElwee suggests that he films his son so incessantly in an effort to thwart the rapidity with which he will drift, the surging away that causes every loving parent great heartwreck. “When I look through a viewfinder,” he says, “time seems to stop. A kind of timelessness is momentarily achieved.” But film, he acknowledges, actually slows down nothing: it’s an illusion, a bitter trick that film plays on our shaky conceptions of time. Still, those innumerable hours of film that McElwee has on the progress of his household are an invaluable contribution to one family’s understanding of itself. What I wouldn’t give to have a cache of home movies of my boyhood—those years of my life are ghosts flitting before me. What I wouldn’t do to be able to see, to know my deceased father in home movies in the same way McElwee’s kids will be able to know him more fully through his films. That’s exactly what McElwee proposes in Time Indefinite: his incessant filming, like the having of children, is a stay against his own mortality.

In Photographic Memory, there’s this memorably accurate line after commenting on how hard it is not to strangle one’s unhinged adolescent: “Teenagers don’t even realize how much they are protected by a smaller version of themselves which rises up to defend them”—every parent sees the vulnerable child still dwelling within the hellacious teen. And in Time Indefinite, McElwee addresses the camera with a speech worthy of Strindberg or Shaw:

Family, always family. In the catalog to the 2012 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival at Duke University, for which he curated a thematic program called “Family Affairs,” McElwee writes: “My films have depended heavily on the viewer’s willingness to accept the profundity of generational continuity—what we owe to our parents and grandparents . . . what we owe to our progeny.” It’s an enormous debt, and one that simultaneously, paradoxically takes as much as it gives. This question of what the generations owe one another is compounded by the complementary question of what the present owes to the past, and what the future will owe to the present always upon us. “We need to determine what that balance is between the past and present and how we remember the past in the present,” McElwee told me. “There is a tendency we all have to romanticize the past or to reframe it in a way that enables us to go on into the future.”

In the Full Frame catalog McElwee discusses the dissolution of his twenty-three-year marriage, a dissolution that has toppled his conception of the last two decades of his life and the documentaries he created during that time. In an aching line about certain scenes from Time Indefinite, the documentary that depicts his marriage, he writes: “These scenes now lacerate—shards of a beautiful stained glass window through which a brick has been thrown.” Such is the bargain made by the autobiographical artist: you get to document your life and then your life lies all around you, in images and words, forever prepared to taunt you with the way your world used to be, to remind you of what you’ve lost.

The weft of his world has been undone by this divorce, and he told me that his film in progress, tentatively titled Redux, “is a portrait of a filmmaker who’s momentarily misplaced his mind”—or lost his grasp on the past/present interchange, which amounts to the same thing. In some footage he showed me, he sorts through boxes of his belongings in his new condo, an array of items on a table, many of them inexplicable to him. One is labeled “grill door,” but there is no grill. The new film will no doubt contend with beginning again in one’s mid-sixties, with the demolished imago of a beloved, and with how one can be both haunted by the living and chastised by the dead—with what McElwee himself once aptly called “the tangle of ironies and connections . . . the little moments in time that seem suddenly to fall into place so that we can see the complexity, and humor, and absurdity of life.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.