My Name Is Alex

By Michelle García

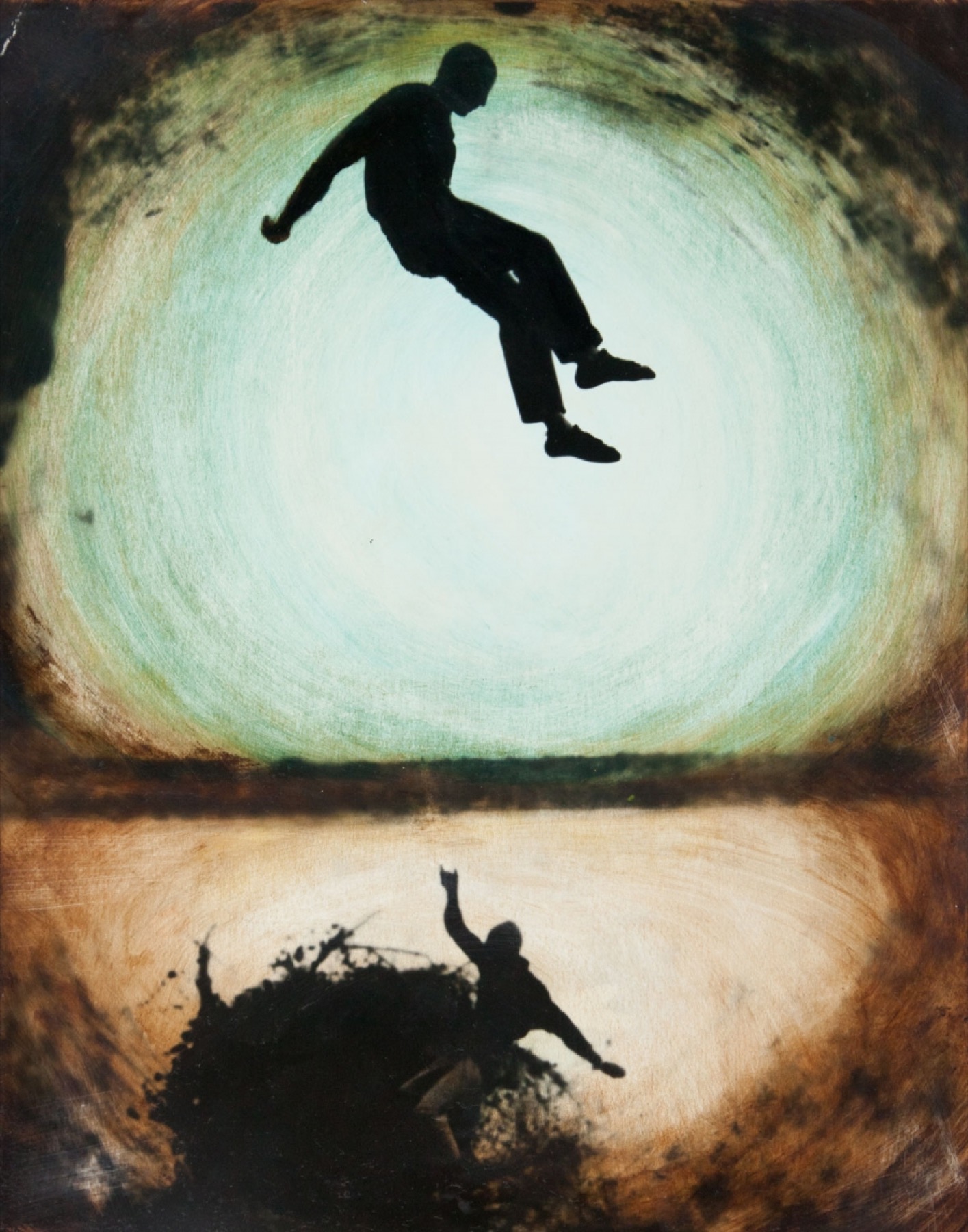

“Falling,” by Josh Verduzco

A boy stood along the highway, his desperation made plain by the way he leaned into the oncoming traffic, flapping his arms while gripping a plastic water jug covered in dust. After the cars rushed past him, ignoring his calls for help, the boy spun around in defeat, his legs nearly buckling beneath him. I watched from the side of the road, at a distance. He spotted another car and began bouncing on his feet, mustering the energy for his next attempt. The boy couldn’t understand why people weren’t stopping. He only needed to get to Houston but he didn’t know that Houston was nearly three hundred miles away.

The Texas borderlands lay 100 miles to the south. Nothing but brush lay for miles around him, nothing but beautiful Texas ranch land, where nearly all living things were born to prick, sting, or bite.

The drivers knew who he was—or rather, what he was. The filthy clothes, the jug of water, the pitiful desperation. They violently jerked their pickup trucks and cars out of his way. These were church-going people, people who say grace before dinner and bid farewell with the words, que vayas con Dios (go with God). Their pickups and cars might well display a fish-shaped decal, identical to the one affixed to my tailgate, containing the word JESUS.

In the evenings, as the land cools, television news reports tell of the latest migrant body found on one of the South Texas ranches. With hundreds of men, women, and children turning up dead each year, the reports have become regular news items. Death is generally blamed on heat or exposure. The TV anchors never mention whether anyone might have seen the migrants on the road and left them to die. They never mention whether the migrant succumbed to indifference and fear.

But reporters often seem to relish offering the particulars of a migrant’s death, the state of undress, the effects of decomposition. Such details, of a fate too horrific to imagine for friends and loved ones, work to push these strangers further into the realm of them. That’s what almost everyone calls the migrants: them. No qualifier or definition needed. I directed my disgust not at the boy but at the passing traffic.

After a few minutes, the boy began turning in circles, falling into an obvious despair. To reach this part of the highway, he had traveled through an empire, the King Ranch, with a landmass greater than Rhode Island. In a day or two, if he continued his journey, the rattlesnakes would get him, or the heat. If he dared return to the brush, the tangle of trees, bushes, and cacti would envelop him, trapping humidity and heat, which by late morning reaches triple digits even in September. The air is stifling, the earth beneath is a rocky sand. There are no straight paths through the cat’s claws, cacti, and the palms known as Spanish daggers.

I was just a few years younger than the boy when my brother and I got lost in the brush while playing a game of explorer. We heard the horn of the old pickup bleating over and over as my father tried to find us. And I remember the terrified look on his face when he did. That afternoon, I learned that death lurks out in the brush, even for children.

Lessons from the ranch tend to form deep grooves in my memory because they involve extremes, life and death. My brother, father, and I once discovered that someone had broken into our one-room cinder-block ranch house, with a chimney and no indoor plumbing, and pilfered the pantry of our potted meats and canned beans. “We have to call the police,” I said, my mind overly influenced by television crime shows. My father responded the way most anyone back then might have. “Mijita,” he said, “you can’t blame a person for trying to eat.”

The South Texas landscape the boy and I now traveled was covered with layers of security: helicopters and planes and surveillance blimps; sheriffs, state police, and federal agents; unmanned aerial vehicles that watched and hunted.

I circled around and pulled over. The boy approached the passenger window. He was no more than sixteen years old. His clothes were in tatters, his thick black hair standing on end, powdered with dirt. “Please take me,” he pleaded. “I’m going to Houston and then to New York.”

“Where are you from?” I asked. “Guatemala,” he replied in the accent of the highland Maya. “How long have you been out here?” The boy explained that he had been traveling with a group when the Border Patrol came around and captured everyone but him. He believed he had wandered through the brush for days.

His distress was so obvious; why did I have to gauge it? I needed to bargain for time. The boy didn’t know this, but I had no safe place to take him and helping him was criminal.

“Please just take me with you,” he said gently. “Take me to your house.” But I didn’t have a house. I was borrowing one from my cousin. With the boy inside, it would become a stash house. “Take me to Houston,” he pleaded, but I couldn’t. I don’t know why, but I couldn’t. Besides it wouldn’t be long before some small-town sheriff’s deputy pulled me over. I am often pulled over. Men with badges have told me that a single woman driving an old pickup truck fits the profile of a drug mule.

The boy had a phone number, some family member or a contact in Houston. Could I at least call them? He began to recite the numbers that he had clearly turned over in his mind for thousands of miles, then he stopped. He couldn’t remember the middle digits. A look of panic came over him and he began banging his head in the air, as if trying to knock free the missing numbers. The sun had scorched his mind.

The skin on the boy’s face had drawn taut, giving him a look of surprise. He was charred, burnt. He looked like a cartoon character after a bomb blew up in his face. Such a silly shameful thought, but it was meant to deflect the indisputable truth that he had the look of someone who would soon be found on a ranch, lifeless under a mesquite tree. The boy finally pieced together a string of digits that amounted to a non-working number.

“Súbete,” I told him, “get in.” He jumped into the bed of the truck and laid flat and stiff, closing his eyes to shut out the sun overhead. If a trucker were to pass by and see the boy, we were busted. If I got pulled over, we were busted.

The sound of the engine and wind slamming against the open window filled the truck cab, creating the sensation of traveling through a tunnel. I dialed the number of a civil rights attorney, which a friend had given me while I had been watching the boy. No one answered. I called the friend, an activist, and told him I had the boy. After he told me I did the right thing by getting the boy off the road, he wished me well, which was the most he could offer. Later, when the boy was gone, another friend mentioned a nearby restaurant where the owner doesn’t ask questions. Only then did I find a local priest who allows migrants to call their families from his telephone and then wait in the courtyard. He stopped inviting the migrants indoors, after a parishioner threw a fuss.

At the first street in town, a town named Riviera that everyone pronounces Rivera, I turned right and headed south. The paved road led to a caliche path that turned to dirt and I pulled over near a small water plant, barely out of eyeshot of the nearby houses.

I turned off the engine and instantly noticed the peace. Doves cried in the distance. The grasses rustled, the mesquite and huisache trees rustled in the breeze coming off the bay miles to the east. The boy sat up in the truck bed and we listened in silence before I explained that he was far from Houston, far from New York, and he had to stop walking. “You will die,” I told him. He knew the words to be true.

I offered to take him to the northbound highway. If you’re lucky maybe a truck driver will take you to Houston, I told him, but if you hang around the migra will find you. I didn’t tell him that if he was unlucky someone might pick him up and sell him, force him to work, or that the local cops would grab him. There’s money to be made from boys like him. Alive, he became another “alien” apprehension, and a reason to pump money into the local police departments.

He weighed his choices silently. If you can consider that he was only three hundred miles away from the end of a journey that had likely spanned weeks—days gone by eating ramen noodles or nothing at all, crammed into safe houses, preyed upon by criminal gangs that exploited his desperation and weakness, beaten and robbed by corrupt police—then you can understand that risking death was a viable option.

On the borderlands, acts of compassion and humanity are buried by laws created by people in faraway places so as to make the word them a cushion against a feeling of utter helplessness. Only when you have offered death to a child can you understand that the laws of the borderlands don’t apply anywhere else within our country.

And that’s why an apology was attached to his only other option: call the Border Patrol. Whatever you do, I repeated, you can’t keep walking. His entire body shuddered, his face crinkled, and his lips curled up to weep—but there were no tears.

“Do you need water?” I asked, leaning on the truck. He showed me his water laying next him on the truck bed. But he was hungry. I offered the half-eaten taquito still in its sack in the truck bed, where I casually threw it the day before. He accepted the bag but waited to eat.

We didn’t have much time. Sooner or later someone would see us and call the Border Patrol. I later learned I had unknowingly delivered us to a notorious rendezvous site used by smugglers. The coyote trail was what my cousin called the dirt path that leads from the nearby reservoir back to the road. I called that cousin and asked for the phone number of the local Border Patrol station and then I explained that I had come upon a migrant boy. He was lost and needed help, I told them, while trying to ignore what their “help” would mean. And I would be gone by the time they arrived.

Before I drove off, I told the boy my name and asked for his. He lifted his eyes. This boy, whose body had been smuggled, stashed away, and then roasted alive as he trudged through harsh terrain, who begged for help and was turned away, looked at me and said, “My name is Alex.” And then, as if he had made a new friend, he smiled.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.