The Legend of Chokoloskee

Searching for Watson in the Ten Thousand Islands

By John O'Connor

“Cypress Slough and Mist, Cypress Lodge, Punta Gorda, Florida,” by Eliot Porter. Courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Back in a tangle of pepper trees, past the rusted skeleton of a Model S Ford, in the black muck and dead-air stink of an abandoned shell-mound island at the western edge of the Everglades, I’m hunting the bones of the outlaw Leslie Cox. For a long time rumor was that Cox, a surly, dark-haired drifter from up around Fort White, Florida, was hiding out here in the Ten Thousand Islands, prowling its knotted creeks and salt marsh bogs, and just might turn up on your porch one evening to settle old scores.

“Unless Watson killed him, which nobody believed, Cox was still there,” Peter Matthiessen writes in Shadow Country, his fictional re-jiggering of this region’s most hard-dying legend. Of course we’re talking ages ago. Cox, even if he did live out his life in this wilderness, is long gone now.

But what I’d been hearing lately was that Cox died young, had in fact been murdered in 1910 some one hundred yards from where I’m kneeling, his body left to rot, and that his killer was none other than E. J. “Bloody” Watson, who was himself gunned down a few days later by a posse of his neighbors on Chokoloskee Island. If true, Cox’s bones could still be stuck in this soft marl, poking up through the years to forever upend the Watson myth. Finding them might finally account for what happened on this unsettled ground a century ago.

So I’m down on my knees, peering into the darkness, scraping my way through snarled limbs of buttonwood and black mangrove, swatting at mosquitoes. But the foliage won’t yield. It’s too thick and ragged and cobwebbed, and there are too many goddamn bugs, not to mention short odds on venomous snakes—diamondbacks and corals and moccasins—and instead of boots I’ve stupidly worn New Balance sneakers, which are officially ruined. After maybe three minutes of searching, I come storming out of the brush, waving my arms in a mosquito cloud, and almost go down hollering in a tangle of ferns. Back at the boat, Capt. Gary McMillin waits, motor running.

“Find much?”

“Watson’s car,” I mumble. Because it’s patently absurd on so many levels, I don’t mention I’ve been looking for Cox’s bones. Say I found something—and just positing that means my brain is awash in crime procedurals—but say I kicked loose some lost shard or fluted shaft, then what? Get it DNA tested? Scrounge up a Cox relative, if there are any, for cross-referencing? And what about the other bones buried out here, all those cane-cutters Watson allegedly killed, and before them the Calusa Indians done in by the Spanish? Cox’s would be just one corpse in a jumbled necropolis and unearthing it would require a dedicated team of crime scene investigators. Besides, why would Watson leave that body behind when he knew it would’ve gotten him off the hook in Chokoloskee? None of it makes sense.

“Imagine living here with no skeeter repellent,” Gary says through his short white beard, nodding to the clearing behind me where the redbrick remains of Watson’s old plantation house bake in the sun next to his cistern and sugarcane kettle, a few paces from a National Park Service Porta-Potty. These ancient killing fields have been repurposed as an NPS campground and are part of the Wilderness Waterway, a ninety-nine-mile-long kayak trail that winds from Everglades City to the town of Flamingo, at the southern tip of the state.

On cue, mosquitoes make for our eardrums. As we shove off, the Watson Place gets quickly swallowed by jungle. In Watson’s day, the Ten Thousand Islands were wild frontier inhabited by plume hunters and ex-cons and moonshiners and rough-hewn “Gladesmen” like Leslie Cox who lived off the land and beyond the law. Watson, Kurtz-like, carved a small empire from this desolate stump of mangrove at a narrow bend in the Chatham River. Gary and I agree it would make a sweet hideout, if you could stand the mosquitoes.

“You get a piece of history out here,” Gary says, his voice straining over the engine growl. “You also get an idea of how people could go crazy being so isolated.”

I’m the sole passenger on the “Bloody Watson” sightseeing tour, an expansive voyage through Watson iconography offered by the Smallwood Store on Chokoloskee, the borderlands town that’s the doorstep to the Ten Thousand Islands. Watson lore has birthed a small tourism industry in these parts, thanks mostly to Matthiessen’s 1990s trilogy Killing Mr. Watson, Lost Man’s River, and Bone by Bone, which were condensed into a single nine-hundred-page volume, Shadow Country: A New Rendering of the Watson Legend, winner of the 2008 National Book Award. You can find the books at the tackle shop in nearby Everglades City, over at the Ranger Station, and at Smallwood’s, a trading post-turned-museum run by Lynn Smallwood McMillin, Gary’s wife and the granddaughter of C. S. “Ted” Smallwood, who was friendly with Watson. Until a couple of years ago, the museum staged dramatic reenactments of Watson’s killing based on its depiction in Shadow Country—he was shot on the beach out back as he stepped off his boat—featuring descendants of the killers and a few of the original guns.

Inside, among shelves of ancient dry goods and cans of “TRAK Insect Surficide, 6% DDT,” is a laminated pencil drawing of a dramatically whiskered Watson, next to an impressively succinct bio: “Bloody Ed Watson (1855—1910) . . . was a successful local cane farmer with a fearsome wild west history. In October 1910, a group of Chokoloskee men met him at the store dock and killed him. They were convinced that he was shooting his farm workers on payday and feeding them to the gators.” There’s a Ten Thousand Islands map with “Bodies Found” written across it in black Sharpie and arrows pointing to where some of his suspected victims were discovered. Gary’s boat tour comprises most of these spots.

Matthiessen, who died last year at eighty-six, grew up hearing the Watson legend during summers in southwest Florida. It struck him, he said, as “a metaphor for the Florida frontier. It’s all there, the racism, the corporate greed, the destruction of the environment, the isolation of the Indian peoples.” He spent three decades collecting stories from surviving witnesses, combing public records, and badgering Watson’s descendants to talk to him while attempting to pry a dead man loose from his afterlife. He knew a good story when he heard it: a mix of Conrad and Faulkner, Virgil and Dante, set in a pitiless landscape. It sustained Matthiessen for fifteen hundred blood-soaked pages (the length of his unwieldy first draft, conceived as a single novel), by far the most prodigious literary eruption of his career.

Something about the Ten Thousand Islands enchanted Matthiessen, too. It’s clichéd but undeniable, the place engineers huge psychic boreholes. Storm clouds both literal and figurative were bound to gather up like omens over homesteads hacked into the horizon, practically floating atop the black water.

Though fiction, the events of Shadow Country are more or less established fact on Chokoloskee. While a few might quibble with Matthiessen over particulars, they’d allow the overall veracity of his portrayal. Perhaps the book’s nearest fictional coeval is Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang, which recasts the real-life Australian bushranger Ned Kelly as a lovably misunderstood folk hero. But try to imagine that Carey’s novel was also Kelly’s official biography, written while the topic was still raw, and elevating it from the realm of myth to the historical record. There are Chokoloskeeans today who believe Watson was mostly innocent, or that his crimes, if you could call them that, were exaggerated, or at least their context—desperate land grabs in ungovernable wilderness during an era when blacks and Indians were murdered with industrial efficiency—should’ve gotten him a pass. To others, Watson plainly had it coming.

No doubt the “Bloody Watson” boat excursion constitutes murder-porn, an odd vein of pseudo-historical voyeurism as puzzling as it is shrewdly contrived. London has its Jack the Ripper “terror walk”; Corleone, Sicily, its “mafia tours.” Despite the otherwise popular affection for bloodshed, I happen to be deeply invested in the tour, having read Shadow Country twice and pondered the Watson mythos to the point of panic. On a limbic level, Matthiessen’s tale of entrepreneurial strivers casting lots in a forsaken backwater feels like a full-bore psychological Thunderdome. The novel is really about vengeance, that baseline response to perceived injustice that dwells within everyone and which we’re lucky to keep at arm’s length. I’ve come a long way to see this place, to reckon with a legend and landscape that wind me up tightly, hoping one might unlock something in the other. The fact is, Gary McMillin, swinging the tiller on a twenty-four-foot Carolina skiff, has captured my Muse.

“This here’s all Watson country,” he yells as we bounce toward a slash of white sand called Rabbit Key, where Watson’s body was interred until the Fort Myers sheriff came to dig him up. Sixtyish and immensely built, with white-blond hair pinned to his head by a once-white sweatband, Gary stone-crabbed out of Chokoloskee for thirty-three years before quitting to help Lynn run the store. When we crunch onto a beach lumped with oyster shells, I catch a nostril-ful of tidal funk and think of Sheriff Tippins’s exhumation morsel at the end of Book I: “Any man going ashore on Rabbit Key can get a whiff of Mr. Watson yet today.”

Sitting there, Gary and I discuss some finer points of Watson’s demise, starting with his arrival in the Ten Thousand Islands in the early 1890s: A deadeye shot in a black frockcoat with a break-top Smith & Wesson who was maybe wanted in Arkansas for the murder of the outlaw queen Belle Starr, Watson “looked and acted like our idea of a hero,” as one resident puts it in Shadow Country. Notwithstanding his rusty Kilmister muttonchops, negligible lips, and beady blue eyes, Watson charmed the pants off the local gals, leaving a brood of blue-eyed gingers in his wake.

Then gossip started up about “Watson Payday,” how he had a habit of killing his black farmhands instead of paying them. It was said he murdered some runaways on Lost Man’s Key; a couple of game wardens; a crazy Frenchman; the hog-lover Green Waller and his woman Hannah Smith, the ex-con Dutchy Melville—all three of whom he gutted and dumped in the current; for a final tally of fifty-three victims, some innocent, some not-so, making Watson the second-most-prolific serial murderer in U.S. history after “Green River Killer” Gary Ridgway. These last murders he pinned on his foreman, Leslie Cox. Unsurprisingly, the Chokoloskee posse—you might also call them a lynch mob—didn’t buy it. Watson wiggled out of that one, departing Smallwood’s in his motorboat, Warrior, and promising to return with Cox dead or alive. The 1910 hurricane came and went. When Watson disembarked at Chokoloskee three days later with a likely story of how he’d shot Cox on Chatham Bend but had misplaced the cadaver, things got messy.

The upshot is the posse tried arresting him, Watson’s gun misfired, and he was thoroughly showered with lead about fifty feet from his wife and children. Even “with all that lead in him, Ed Watson kept on coming … that was the demon in him… . He never crumpled but fell slow as a felled tree.” The men hitched a rope to the body and towed it out to Rabbit Key, plunked it in a hole, covered it with slabs of worm coral torn loose by the hurricane, and called it a day. Thirty-three bullets were eventually plucked from Watson’s mangled corpse, not counting buckshot.

Pretty much all of this is covered in Shadow Country. Except for the stuff about Cox’s bones remaining out at Chatham Bend. In Book III, Watson’s final reckoning with Cox is cut short by some Mikasuki Indians who have a serious ax to grind with the foreman. Matthiessen, in a sleight-of-hand that eschews a tidy comeuppance for Cox yet accounts for his disappearance, leaves his fate open-ended: “Somewhere in the backcountry of America, an old man known in other days as Leslie Cox might still squint in the sun, and spit, and revile his fate.”

According to Lynn McMillin, plenty of folks wouldn’t talk to Matthiessen when he came to Chokoloskee asking prickly questions, so he likely never heard the story of Cox’s bones.

“People down here don’t trust outsiders,” Lynn had told me earlier that day, back at the Smallwood Store. “They felt like even after all this time there’s things that’re better left alone.”

But Lynn hadn’t heard the story of Cox’s bones either. It seemed nobody had. Until one afternoon in 1993, three years after Matthiessen’s first Watson installment came out, when an old man appeared at the store spinning a curious yarn.

“He was practically dead himself,” Lynn recalled. “Ninety-four, ninety-five”—which would’ve made him about ten at the time of Watson’s death—”he stood right there and said he and his daddy had gone down to Chatham Bend three days after Watson was killed and found Cox’s body hung up in the mangroves.” Leery of getting embroiled in the whole mess, they kept their mouths shut. “He said what many folks here suspected: Watson was telling the truth.”

Lynn wouldn’t say the man’s name, only that he passed away years ago. She led me outside and under the store, which rose on pilings at the edge of Chokoloskee Bay, the beams clearing our heads by a half-foot. As Lynn shuffled along, a skein of fatigue clung to her. Just the day before, she’d been in Naples signing settlement papers in a lawsuit against Florida Georgia Grove, a developer that had wanted to build on the land next door, doing away with the only road leading to Smallwood’s. The settlement preserved the road but did little to assuage Lynn’s feelings about that timeless Florida scourge: developers.

Lynn wanted to show me the beach where Watson was gunned down. Tramping the developer’s fence, we skirted a cement seawall, pausing at a spot of washed-out scrub.

“Right here’s where he got it,” she said. It smelled of freshly mowed grass, matted seagrape, saltwater. Bits of Styrofoam were tossed about, some fishing line, the cap to a Penn tennis ball container. Lynn was raised amid bogeyman tales of Watson’s misdeeds. Tales passed around the dinner table often acquired a new twist. But her late aunt Thelma, who witnessed the shooting as a six-year-old, recounted it exactly as Matthiessen does in Shadow Country, from Warrior’s steady put-put-putting up the coast to the hard scrape of the hull as Watson grounded it at Smallwood’s to his acrobatic dismount in front of the Chokoloskee posse: “Timed his move forward as she went aground and jumped as the bow struck, holding his shotgun up across his chest and twisting in the air so’s to land where he could cover the whole crowd,” Matthiessen writes.

We headed back.

“There’s other things that aren’t in the books,” Lynn said. “Like the reasons why they killed him in the first place. Matthiessen didn’t get that story either.”

A thin cast of twilight was rising in the west as we climbed the steps into the store. Across the water, an osprey banked and dipped over the tree line.

“Watson was a serial womanizer,” Lynn said. “That’s why they killed him. He had deflowered several women and had illegitimate children all over the islands. The families got tired of his crap.”

This had a hard-bitten ring of truth. Actually, Matthiessen hints at it early in Shadow Country: “[H]is mannerly ways was fatal to women all the time we knew him.” Despite the gossip about “Watson Payday” and his infernal backcountry dealings, there was little evidence he’d ever killed anyone (except for Belle Starr—more on that later), and some in that posse may have been personally motivated. Of course, anger isn’t so easily distilled, even in revenge. After the hurricane, everyone was riled. Some men might’ve simply been sick of feeling afraid, while others were led by their neighbors. As in many small, isolated places where feuds escalate and turn violent, things happen that are beyond anyone’s understanding. In the moment, it can be hard to know whether you’re doing someone else’s bidding.

Whatever their reasons, it’s easy to sympathize with those men, who weren’t bad men, most of them, and who must’ve metabolized Watson’s presence in their community as a parasite sucking the life-force from the host organism, which, in the absence of law enforcement, they felt obliged to purge by themselves.

“Some of the things Watson did were justified,” Lynn told me. “It was a lawless area. But those men thought it was their job to get rid of him. And they did.”

If I heard her right, the line Watson walked between life and death had an uncanny logic to it. His killers simply deduced its ending. You also have to feel for Matthiessen. An existential masochism attends entrenchment in the Watson legend. The constant toggling between fact and fiction, between what’s been said and what hasn’t, by whom and to what ends, produces a distancing effect that funnels you down paths that gradually disappear. No matter which you choose—say, one out on Chatham Bend leading to Leslie Cox’s bones—Watson comes back as motley and chewed up as ever. In 1999, Matthiessen told Charlie Rose that his version of Watson “is what I intuit, because there’s so few hard facts” and “the legends about this man are so numerous and mostly all wrong.” It’s tempting to see in Matthiessen a shadow of Watson’s son Lucius, who undertakes a painful reconstruction of his father’s murder in Book II amidst enduring rancor and misdirection on Chokoloskee: “Just when he thought he was getting things sorted out, local rumor had turned things murky yet again.” Or as Gary puts it during our ride through the hellishly coiled backcountry, where rivers and creeks and inlets sprout ancillary fingers that twist and drown in an ocean of mangrove, “It makes you want to go in a thousand directions at once.”

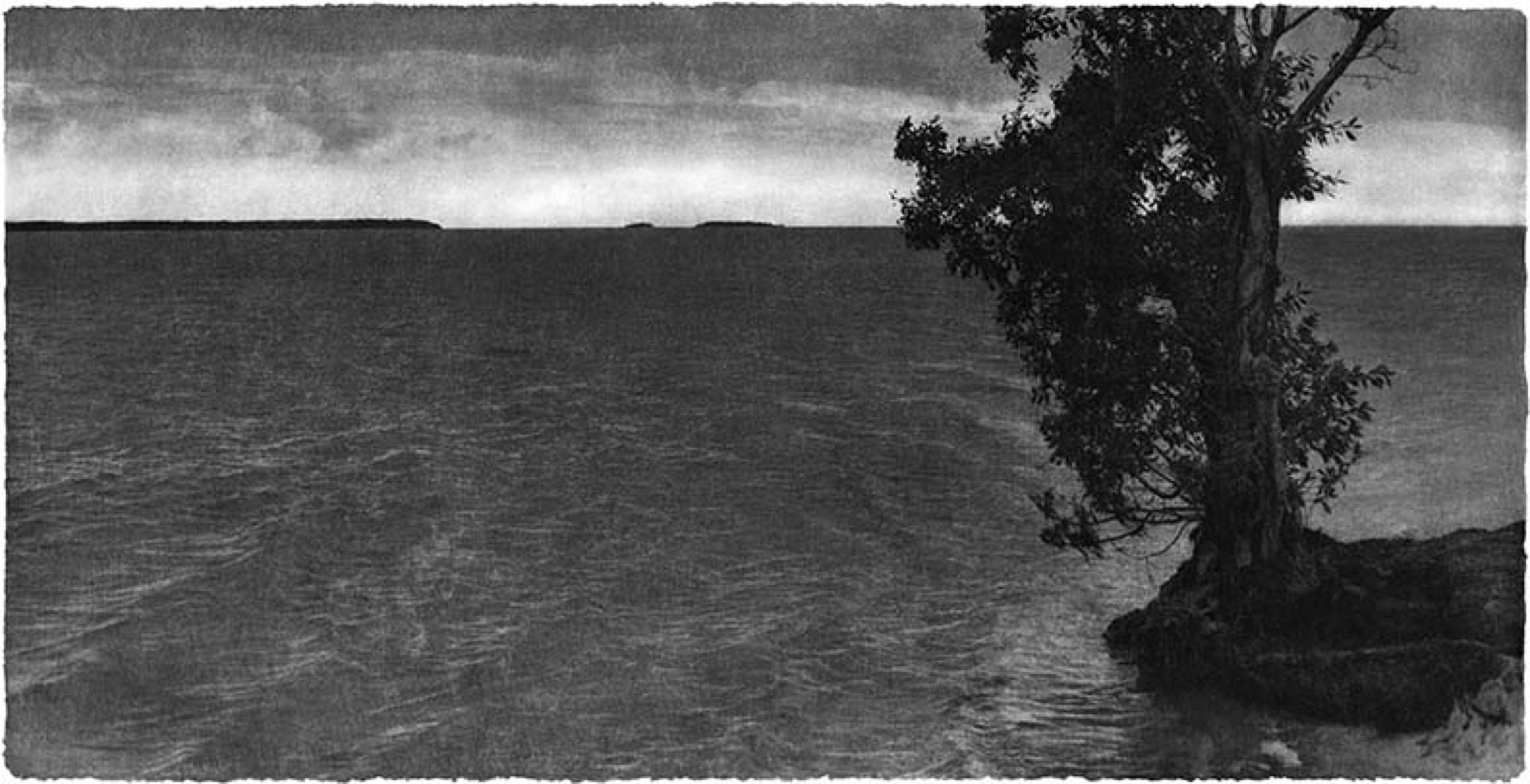

“Everglades 14,” archival pigment print (2014). © Jungjin Lee 2015

“Everglades 14,” archival pigment print (2014). © Jungjin Lee 2015

About noon the next day I set out from Chokoloskee in a kayak borrowed from Lynn McMillin. I bring my fly-rod and cast around for snook and redfish. I’d wanted to paddle out to Rabbit Key and camp where Watson’s body had lain. But a small-craft advisory called for heavy chop that far offshore. A ranger at the NPS station, where I stopped for a camping permit, openly challenged my backcountry gravitas, clucking at my dry sack—too small for a tent but just right for a can of Pringles and four tallboys of Coors Light—telling me, in so many words, that were I to get stuck out there they wouldn’t be inclined to come fetch me.

Instead I strike a northwest tangent across the bay, casting as I go. The sky is the color of a Blue Colada, icy and blinding. A pair of bottlenose dolphins rise ahead of me, their dorsal fins breaking the surface in tandem as they drive mullet against an oyster bar. An ibis strolls out of the shadows, a blur of ivory with ink-dipped wingtips; “Chokoloskee chicken” were once slaughtered by the tens of thousands in the Everglades, their plumes sold for women’s hats, their meat salted and shipped to Cuba. Watson hunted them in droves. As did his neighbors. Until there were hardly any left. A vein of destruction runs through Shadow Country, of nature mutilated and eroded by man, of man’s own tireless capacity to cloak himself in suffering.

At Sandfly Pass the wind picks up and blows my line in my face, so I head back across the bay toward the shelter of the Turner River. At the river mouth I shake my copy of Shadow Country from my dry sack and flip to a gory early scene recounted by Bill House, who would later become one of Watson’s executioners: “Every alligator in the Glades was piled up in the last water holes, and one day out plume hunting, I come on a whole heap of ‘em near the head of Turner River . . . Me’n Ted [Smallwood] and a couple others, we took forty-five hundred gators in three weeks . . . They was packed so close we didn’t waste no bullets, we used axes.”

Thankfully the gator trade has dried up in the Islands, which today lie mostly within the Everglades National Park, a federally protected reserve of 1.5 million acres. As a symbol of man’s sprawling stupidity and waste, followed by his eleventh-hour attempts to undo monumental ecological disaster, it doesn’t get much grander than the Glades. Before it was dredged and dynamited and sub-divisioned nearly to oblivion, the Everglades measured five times its current size, part of an eleven-thousand-square-mile watershed stretching from just south of Orlando all the way to Florida Bay. Although it contains swampland, the Glades are technically a river, as wide as sixty miles in places, flowing at the rate of about a quarter mile per day. Starting in the 1920s, the Army Corps of Engineers tried to drain most of it into the ocean, building hundreds of miles of canals and dikes and pump stations in what was essentially a massive real estate scam to protect land for corporations like Alcoa and U.S. Sugar. Half of the Everglades wetlands was destroyed, more than 90 percent of its wading birds and alligators killed. By the time Harry Truman signed the park into law in 1947, the wood stork, American crocodile, Florida panther, manatee, and snail kite—a small hawk with sherbet-orange talons and a predilection for aquatic apple snails—were almost gone, as were native cypress and black mangrove. Then on the eve of the 2000 Bush-Gore debacle, Congress passed a $7.8 billion last-ditch plan to save the Glades, which, if it ever gets its legs, will be the largest environmental restoration project in history.

And yet you don’t sense any ruin where I’m paddling. It feels wild, primeval. Turner River’s gators have retreated east with the freshwater into the sawgrass. I head up the Lopez River, just off to the south, passing through a long corridor of mangrove and hammocks of buttonwood and gumbo-limbo, beneath airplants as big as my torso. The whole package feels vapor-shrouded and motionless, like a greenhouse into which the light is beating straight in.

For the next few hours nothing much happens. The water turns from blue-black to macchiato to bottle-green and back again. I cast to all the spots that look promising. Zilch. My arms get sore from casting. I snag my line on a piling, break off, and stew over that for several minutes before retying.

Big expectations in fly-fishing tend to unravel spectacularly. You do everything right, kill yourself on prep work and logistical heavy lifting, get on the water at the right hour with the right flies and plug away till your hands turn pink and neurons dribble from your nostrils . . . and the fish give you the middle finger. But I’m content to drift along, trying not to judge myself too harshly. I love this lonely place, its fitful silences, its refusal to bend to one’s wants.

Thirty years before Shadow Country, Matthiessen won another National Book Award for a nonfiction work, The Snow Leopard, about his expedition to the Himalayas in search of the elusive predator of its title. (He’s the only writer to win in both fiction and non-.) For all its metaphoric mining of natural phenomena, The Snow Leopard couldn’t differ more from Shadow Country. As spiritual autobiography, it’s a quiet book, too quiet for my tastes, albeit with many dazzling passages, but almost totally devoid of drama. I can think of only two instances where the tempo shifts up a gear ever so slightly before returning to its unearthly quiet. But the books share a minor chord. The Snow Leopard, like Shadow Country, is preoccupied with the loss of a father. Prior to the expedition, Matthiessen’s wife, Deborah Love, died of cancer, and he abandons their eight-year-old son, Alex, to undertake the months-long trip, something that eats at Matthiessen throughout.

It’s less oblique in Shadow Country. Book II unwinds as a long rumination on what a murderer bequeaths to his sons: Lucius Watson, driven nuts by his father’s death, torpedoes his own life in a fruitless search for the truth. His half-brother, Rob, has it worse off; you sense early on he’s chasing his father into the ground. Their bewilderment is understandable. In some ways, Ed Watson wasn’t so different from countless other white men in frontier America. Given another fifty years, he might’ve been a prosperous Fort Myers developer with a two-car garage and fixed-rate mortgage, a marvel with a nine iron, goading his boys into backyard slap-fights. Instead he became a hideously deranged killer (as Matthiessen tells it in Book III, Watson’s own father was a vicious drunk who tormented the boy throughout his childhood). The fatherless sons, Rob and Lucius, emerge as two poles of Watson’s conscience, circling each other, trying to make sense of their legacies.

Their losses don’t compare to Henry Short’s, for my money the saddest character in the whole Watson trilogy. Another outcast ditched by his father, Henry, a black man, has the additional misfortune of being quick with a rifle. Forced by his white benefactors to join the Chokoloskee posse, he plays a pivotal role in Watson’s death, an act for which he’s later repaid by being driven from town toward a gruesome end, purely from the meanness of white folks. This is another preoccupation of Matthiessen’s: the void between white and black, the rich and powerless, that has defined our continent. While Henry has white friends, they don’t quite care enough to save him. Just like nobody cared much when Watson was supposedly butchering black cane-cutters. Offing white people is what got Watson killed. Black lives were erasable.

The kayak has been murdering my back all day. The seat is made of knives, broken glass, railroad spikes. By six o’clock, still fish-less, I’m a slab of dead nerves from mid-thigh to my twelfth vertebra. Mosquitoes charge onto the river. I’ve forgotten to bring bug repellant and have to stop casting to slap my neck and ears. I’ve had enough. Un-scrolling my laminated nautical chart, I try to fix my position. Is that east or west? Is the tide coming in or going out? Swiveling my head around, the entire horizon appears warped and twined in mangrove. A single thought comes to mind: Uh-oh.

Nobody knows for sure whether there are actually 10,000 islands in the Ten Thousand Islands. It’s impossible to keep track. Old ones get washed away and new ones appear where there hadn’t been any before. Rabbit Key is a third the size it was a generation ago and will shortly vanish, its red mangroves carried off by the tides. Others, like the Watson Place, are sturdier shell middens built by Calusa Indians before they were exterminated by the Spanish, though these too are slowly vanishing. My chart puts it as such: “Area subject to constant change.”

It gets dark out. I can’t see much. The kayak pitches diagonally across the waves, water splashing into the cockpit and soaking my shorts. I notice I’m merely being pulled along by the tide, so I rest my arms, hoping for the best. A motor churns faintly somewhere ahead. Rounding a bend, Chokoloskee suddenly appears as a few scattered lights in the distance. Slogging through the foam, I thank the night stars.

In the morning I call a number Lynn gave me. A man answers, says his name is Alvin Lederer. Says he’s the official spokesman for Watson’s kin. Says don’t bother, they won’t talk to you. Says he keeps a photograph in his wallet of Ed Watson instead of his parents. Says he has spent twenty-five years researching Watson and knows a thing or two, like the identity of a man whose father found Leslie Cox’s body on Chatham Bend back in 1910.

“Name was Ed Smith,” he says. “I knew him when he was seventy. He told me that after the hurricane his father had come across Leslie Cox’s body with a bullet hole in his head. He was hung up in the mangroves. His father said not to tell anyone.” Alvin lets this sink in. “Ed Watson killed Leslie Cox just like he said. Had him in his boat. Shot him in the head and he fell overboard, then his body washed ashore.”

Alvin, it becomes clear, runs a kind of one-man Watson Innocence Project, contesting Watson’s guilt for anyone who’ll listen. Although he has never been to Chatham Bend nor seen the river country where Leslie Cox roamed, he has iron springs from Watson’s bed and shards of glass from his windows. He knows Watson’s great-granddaughter, Edith, he says, who lives nearby and “has a head of red hair like E. J. Watson.” His tone is exasperated, not curt, but lawyerly, like he’s dead tired of explaining to folks what is self-evident, and he tends to punctuate sentences with a declarative “Yessir.”

“There’s no proof that Watson killed fifty-three people,” he says. “I have documentation! Yessir.”

What about Belle Starr? I ask.

“Oh without a doubt he killed her. I have here a copy of the warrant for Watson’s arrest. But he was blamed for other murders he didn’t commit.”

Alvin says Belle Starr—a known associate of the James and Younger gangs—had blood on her hands, and anyways Watson was acquitted of her murder. We split hairs over other Watsonian minutiae: why he didn’t light out for Key West knowing the Chokoloskee posse was waiting; whether his shotgun was even loaded; what Cox must’ve been thinking when Watson came for him; and who fired the first shot at Smallwood’s.

“Henry Short was the one who killed Watson,” Alvin says, spelling out what Matthiessen cleverly obscures. “He shot him straight through the chest. Then everybody else shot him because they all liked Henry and you can’t have a black man shooting a white guy in 1910. He would’ve been lynched. They couldn’t say anything afterwards because they’re all accessories. Yessir.”

I read Alvin a quote from Shadow Country where Erskine Thompson qualifies Watson’s guilt: “With so many stories growed up around that feller, who is to say which ones was true?” But Alvin is decidedly untroubled by the prospect of parsing fact from legend, of detangling a fictional wormball that has morphed into history. His research, he says, suggests plumb lines of delineation.

“I’m the only person to study Watson as much as Matthiessen,” he says. “His first book is ninety-nine percent true. The other two aren’t worth the paper they’re written on.”

I ask him what he means. “Nobody objected to Shadow Country when it came out. But it’s Peter’s version of E. J. Watson. I’ve spent years trying to prove him wrong.”

But Matthiessen never claimed to be telling a true story, I say. That’s why he called it a novel. While I sympathize with Alvin’s intense literalism, the notion that Matthiessen got anything wrong seems preposterous, like arguing that Tolstoy flubbed his portrait of Napoleon by failing to mention he was terrified of cats. Alvin swats this away. What vexes him to no end are the false assumptions about Watson he says Matthiessen’s books promote, even as fiction.

“I know Watson was innocent,” he says. “He played with his reputation because it was beneficial to him in the Ten Thousand Islands, but he was no serial killer.”

Alvin starts spitballing. “I talked to a man whose father played fiddle at the Watson Place. He said everybody got along. Nobody ever talked about Watson killing anyone … Watson hired drifters to harvest his cane, kept ‘em in alcohol and tobacco. In the end they owed him more money than he owed them, so they left quietly … It’s fascinating, in all my years of research, I’ve never found any evidence of murder. Actually, I found out a lot of good things about E. J. Watson. Yessir.”

He tells me to Google a book called The Singing and the Gold, another take on the Watson legend by an “A. B. Matthiessen,” a pen name for its husband and wife co-authors. From what I can tell, it’s a lurid Fifties potboiler—”Maybe Ed Watson was too big for the Ten Thousand Islands, but too little to be a man,” that sort of thing—written by Barbara Heggie Matthiessen and A. W. Matthiessen. I turn up an article in which Peter Matthiessen disavows any connection to The Singing and the Gold or its authors: “No relation and I never read the book. I was hoping no one would find out about it. It makes for a gossipy type of item. I’d rather people focus on the merits of [my] book itself.”

“I asked Peter if he was related to them,” Alvin says. “He said no. I just find that hard to believe.”

It’s an odd coincidence, I confess. But what am I missing? At worse, Matthiessen got the idea for his trilogy from people to whom he might’ve been related. Alvin sniffs something more nefarious at hand.

“Peter was a liar,” he says. “He was in the CIA and lied about it.”

In 2008, Matthiessen did admit to having worked for the Central Intelligence Agency in the early 1950s and founding the Paris Review as his cover, which he hid from the magazine’s co-founders.

“You think he lied about being related to those other Matthiessens?” I ask.

“Look, personally, I liked Peter. But in the CIA you have to be able to lie.”

Before we hang up, Alvin says he’ll email me some Watson stuff that’ll blow my mind. I get a bunch of emails from him. No text. Just blurry photos of Watson’s house in its prime, of a puffy Watson in a sharp black suit and flowing whiskers. There’s an arrest warrant for an “Edgar A. Watson” issued on Feb. 8, 1889, by the U.S. Court Western District of Arkansas for the murder of Belle Starr, along with a New York Times article from the next day:

‘Bill’ Starr, husband of the notorious female outlaw who was assassinated near Eufaula, Indian Territory, arrived here this morning with Edgar Watson in custody. He charges Watson with the murder. Watson is a white man, and came from Florida a year ago. The murder occurred near his farm, and Starr claims that the trail from the scene of the crime led to Watson’s house and was made by Watson’s boots. The prisoner was placed in jail.

There’s also a bizarre piece from the Atlanta Constitution written not long after Watson landed in the Ten Thousand Islands:

Captain E. J. Watson . . . tells a remarkable story about his farm. He says that centuries ago when the Spaniards invaded Florida they found a tribe of Indians in the southern portion of the state who were gigantic in size and fierce of temper. The story goes that these Indians were driven back to Chatham river by the Spaniards and there the aborigines made their last stand. The tribe was caught, like rats in a trap, in a bend of the river and was exterminated.

“Signs of that desperate battle are everywhere visible now,” said Captain Watson. “My farm is literally covered with huge skulls and bones, the ground being so rich from the decayed bodies that I grow phenomenal crops. The bones show these Indians to have been nearly eight feet in height, broad of shoulder and mighty of arm. The remains are scattered over the ground, singly and in groups; some are intact, while others are crushed as by blows of mighty battle ax or mace.

I find more photographs on Alvin’s Facebook page, including one of Henry Short. He’s sitting on a stack of crates at Smallwood’s, slouched in the sun with a foot up and a hand raised, perhaps scratching his head. Far more than the image of Watson, it’s jarring seeing Henry—who met such an awful end in Shadow Country—transmuted in this way, rising and climbing into the present. I can’t help thinking of Roland Barthes’s line about photography’s kaleidoscopic twist of time and mortality: “He is dead, and he is going to die.” In that instant, Henry could be waiting on his woman, or resting his eyes in the fierce light, or nursing a hangover. The sight of him feels like a remembered dream, or a narcotic intrusion on reality.

On my last day on Chokoloskee I drive over to Outdoor Resorts, an RV park and marina at the island’s north end. The streets are bare. Brown pelicans cast baleful looks at a few Chris-Crafts and Sea Rays headed out with the tide. Just eight miles from tourist-choked I–41, the town has a shipwrecked feel to it. The year-round population is pushing four hundred, the economy based entirely outdoors. There are airboat tours and bird-watching tours and “swamp-buggy” tours. Fishing khaki and University of Florida Gators apparel are the prevailing aesthetic. Most people seem like they just returned from fishing, or like they’re about to go fishing, or are planning when they’re next going fishing.

It wasn’t always this quiet. Back in the 1980s, when Everglades waters were permanently closed to commercial boats, scores of local shrimp and mullet-men and stone-crabbers turned to marijuana smuggling, some running as far as Colombia for shipments, others unloading bales from mother ships out in the Gulf, then like the gator poachers and rumrunners of old, eluding law enforcement by plunging into the Ten Thousand Islands. An enterprising man could make $20,000 a night. Fancy new cars popped up in town. Before you knew it, there were bar brawls, a pistol-whipping. When federal agents descended, many of the adult males in Chokoloskee and Everglades City—some one hundred men—were arrested, including nearly the entire stone-crab fleet. Folks say there’s still money hidden back in those mangroves.

At Outdoor Resorts I shake hands with Kenny Brown. Garrulous and deeply tanned, in jeans and a white guayabera, Kenny is a connoisseur of Watson lore, his reach rivaling Alvin’s. Kenny’s great-grandfather, Willie Brown, is mentioned in Shadow Country, and his grandfather, William Brown, witnessed Watson’s killing as a boy. Kenny recalls Matthiessen visiting William on and off through the years to talk about Watson.

“Grandaddy Brown was the only guy still living that was there when it happened,” Kenny says. “He saw it all go down. He’s the one who told Matthiessen half of what’s in his book, told him about the black frock coat Watson wore and the pistol he carried, said Watson toted it in a shoulder harness but couldn’t get to it when his shotgun misfired.”

I ask Kenny if his grandfather knew what became of Leslie Cox.

“Grandaddy Brown said Cox was in the lookout at the Watson Place when Watson come for him. I guess he assumed something wasn’t quite right and he started running back through the woods. It’s likely Watson tried to talk to him and Cox raised his gun, and that was the end of him. Local fellas found the body about a hundred yards back on Chatham Bend. They were scared to turn it in.”

“Did your grandfather tell Matthiessen that story?”

“I don’t know. If he did, Matthiessen was smart enough to leave some mystery in the books, keep people guessing, you know?” It’s that mystery, I finally realize, which I’ve attempted to spoil.

Kenny pulls out a paperback of The Singing and the Gold and lays it on the counter. “What do you make of that?” he says.

The cover shows Watson at the edge of a jungle, his face in shadow, looming over a slender woman in a low-cut white dress, golden locks kissing bare shoulders. It’s “Emmanuelle in Chokoloskee.”

“I wouldn’t want to make Peter look bad,” Kenny says. “But I bet you A.B. was his daddy. Matthiessen’s family had a house in Sanibel over in Lee County, which is how Peter heard about Watson in the first place. It’d make sense.”

We chew on this.

“Or maybe he just didn’t want people knowing his story had already been wrote,” Kenny says. “The truth is, folks here knew the Watson legend well ahead of Peter Matthiessen, or A. B. Matthiessen for that matter. Long as that building is standing over there”—he points towards Smallwood’s—”and people like us keep the legend going, it’s gonna stick. We have other stories, but this is the best.”

Curious about the Henry Short photograph, I call Alvin back a few weeks later. He’s fuming about “Florida crackers,” having received some threatening Facebook messages from people who don’t appreciate his Watson research, which he posts on Florida history blogs. As a Yankee transplant to Ocala, Alvin says he has never been trusted by Chokoloskeeans.

“They said if you come down to Chok we’re gonna kick your ass,” he says. “Now I know how Watson felt. Thirty people supposedly shot him. You couldn’t get thirty people in Chokoloskee together in a boat. They’d all kill each other. They’re like crabs in a bucket. One of ‘em starts to climb out, the others pull ‘em back down.”

I mention the Henry Short photo, how surprising it is considering all that befell him, how it seems to communicate something about the Watson legend I can’t put my finger on, something heartbreaking about the bottomless strands of racism and cruelty scrawled across our past. Alvin stops me. That may be so, he says, but actually Henry Short remained in Chokoloskee for years after Watson’s death, married and made a living fishing up and down the coast, then moved up near Immokalee, where he lived to a ripe old age, died a beloved elder of his community. Lucius, too, lived peacefully in the Chok Bay Country, got along fine with his neighbors, and without any badness over the Watson stuff. He died in 1970 at age eighty-one and was buried in the family plot in Fort Myers a few feet from his daddy, Edgar J. Watson.

“There’s several sides to this coin,” Alvin says. “Yessir.” We leave it at that.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.