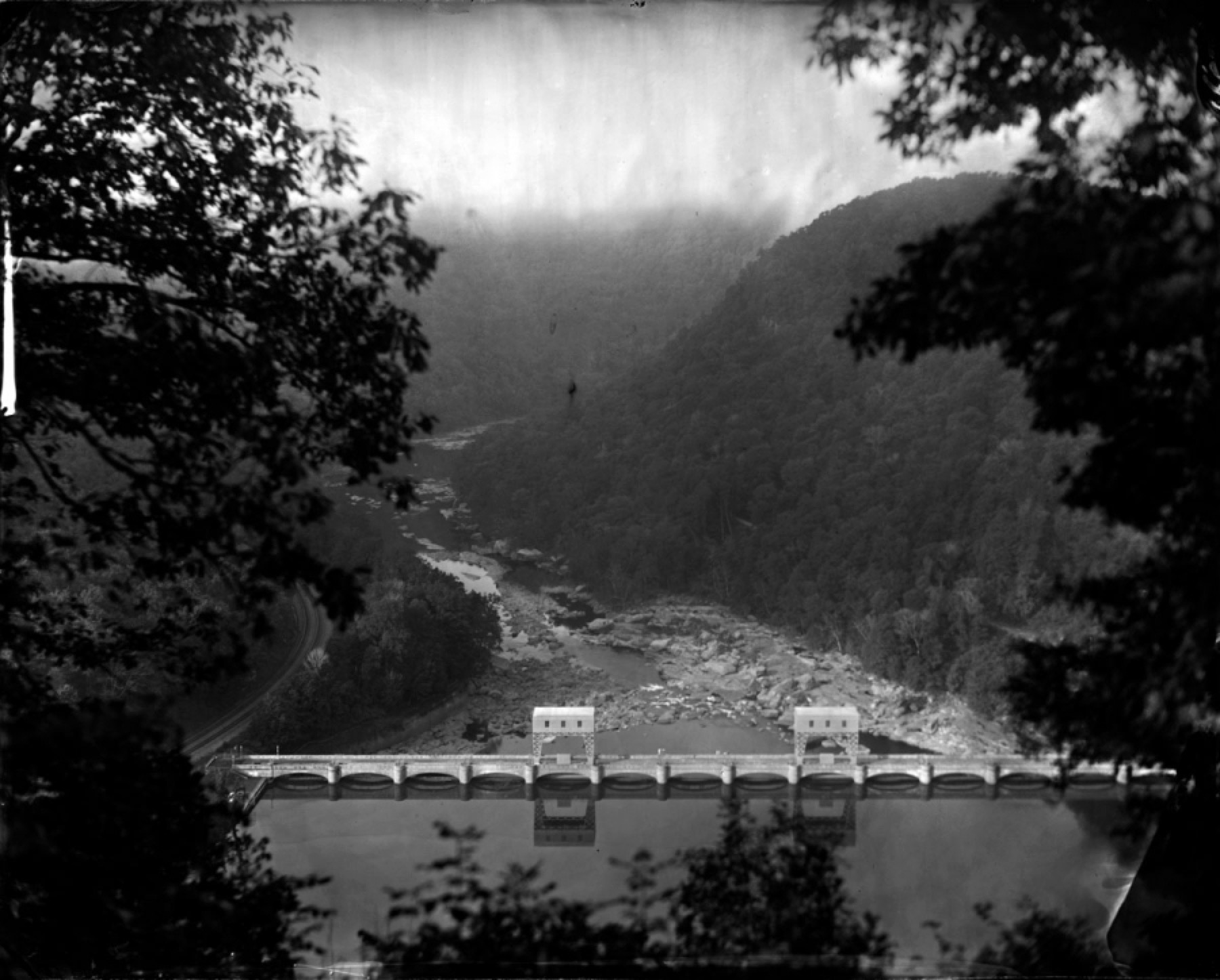

Above the Hawk's Nest Dam on the New River. All photographs © Lisa Elmaleh

The Book of the Dead

In Fayette County, West Virginia, Expanding the Document of Disaster

By Catherine Venable Moore

These are roads to take when you think of your country / and interested bring down the maps again

I was three years old when the Killer Floods hit West Virginia. We were spared, my family and I. My parents had recently bought a stone cottage in a hilly Charleston neighborhood with great schools. Dad had just graduated from law school. We lost nothing, while thousands of our neighbors were ejected from their homes into the icy November waters that claimed sixty-two lives; the 1985 storms still sit on the short list of the most costly in U.S. history. In the aftermath, newspapers accumulated the miracles and spectacles. An organ caked with mud, drying before a church. The body of a drowned deer woven into the under girders of a bridge. Two nineteenth-century mummies that had floated away from a museum of curiosities in Philippi, recovered from the river.

None of this suffering was ours. “Ours.” My mom—a ginger from the low country whose freckles I was born to—packed me up for a week of relief work in a hangar at the National Guard Armory. Her task was to deal with the hills of black trash bags, sent to Appalachia from abroad, stuffed with clothing that recalled dank basements and dead people’s closets. For endless hours she sorted it into piles by age, size, sex, and degree of suitability. Meanwhile, I dressed up in the gifts of the well-meaning and the careless. Stiletto heels. Crumbling antique hats. Tuxedoes, gowns, belts, and bikinis. “Nobody wants to wear your sweaty old bra, lady,” my mom muttered to one of these imagined do-gooders, tossing it aside. On the contrary—I did, very much! I modeled the torn, the stained, and the unusable, cracking up the other volunteers. Mom saw how little of the clothing was functional, how much time was being wasted in the sorting, but she was desperate to be of use.

Disaster binds our people to this place and each other, or so the story goes. Think of the one hundred and eighteen mine disasters our state has suffered since 1894, the fires, explosions, and roof falls. Or the floods, whether “natural”—like the one this June that killed at least twenty-three people (as I write this, my friends come home from recovery work, stinking of contaminated mud)—or those induced by humans, like the coal waste dam that burst at Buffalo Creek in 1972, when one hundred and twenty-five people drowned in a tsunami of slurry. (Pittston Coal called it an “act of God.”) Other disasters are less visible, inside our bodies even: the rolling crisis that is black lung disease claims a thousand lives every year, while an addiction epidemic seems to be robbing entire generations of our children. West Virginia’s drug overdose death rate is the highest in the nation. Then there is the toxic discharge: from the 2014 Elk River chemical spill that poisoned the water of 300,000 residents to the micro releases leaking daily from the sediment ponds that serve mountaintop removal sites.

Appalachian fatalism wasn’t invented out of thin air. If your list of tragedies gets long enough, you start to think you’re fated for disaster. And maybe the rest of the country starts to see you that way, too. I watched a documentary last year about the outsized influence of extractive industries here. It was a well-rehearsed narrative, this litany of disaster—land grab, labor war, boom, bang, roar—on and on in the dark theater. I admired the film in some ways—the bravery of naming each and every pain, the courage of its makers to pass into the tunnel of it, to point fingers along the way. But as I sat through this latest iteration of Appalachian grief writ large, I began to seethe—not at some alleged oppressors, but at the narrative itself. I cannot live inside the story of this film, I remember repeating to myself, like a chant. That can’t be my story because nothing lives there.

Admittedly, there’s a spellbinding allure to disaster, close cousin of the sublime. Hypnotic and wordless, the disaster repulses even as it propels one’s attention toward it. I know, because I’m victim to its seduction, too. I live five miles from where the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel tragedy unfolded, along the New River Gorge in Fayette County. Hawk’s Nest is an extreme in a class of extremes—the disaster where truly nothing seemed to survive, even in memory—and I have made a home in its catacombs. The historical record is disgracefully neglectful of the event, and only a handful of the workers’ names were ever made known. What’s more, any understanding of Hawk’s Nest involves the discomfort of the acute race divide in West Virginia, seldom acknowledged or discussed. Indeed, race is still downplayed in official accounts. Disaster binds our people, maybe. But what if you’re one of those deemed unworthy of memory?

HERE’S WHAT WE KNOW: BEGINNING in June of 1930, three thousand men dug a three-mile hole through a sandstone mountain near the town of Gauley Bridge for the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation. The company was building an electrometallurgical plant nearby, which needed an unlimited supply of power and silica, and the tunnel was determined to be the cheapest and most efficient source of both. A dam would be built to divert a powerful column of the New River underground and down a gradually sloping tunnel to four electrical generators; the ground-up silica rock harvested during excavation would be fed into the furnace in Alloy.

Three-quarters of the workers were migratory blacks from the South who lived in temporary work camps, with no local connections or advocates. Turnover on the job was rapid. By some reports, conditions were so dusty that the workers’ drinking water turned white as milk, and the glassy air sliced at their eyes. Some of the men’s lungs filled with silica in a matter of weeks, forming scar tissue that would eventually cut off their oxygen supply; others wheezed with silicosis for decades. When stricken, the migrant workers either fled West Virginia for wherever home was, or they were buried as paupers in mass graves in the fields and woods around Fayette County. The death toll was an estimated, though impossible to confirm, 764 persons, making it the worst industrial disaster in U.S. history.

If the company had wet the sandstone while drilling, or if the workers had been given respirators, most deaths would likely have been avoided. Yet through two major trials, a congressional labor subcommittee hearing in Washington, and eighty-six years of silence, neither Union Carbide nor its contractor—Rinehart & Dennis Company out of Charlottesville, Virginia—has ever admitted wrongdoing. Calling the whole affair a “racket,” in 1933 the company issued settlements between $30 and $1,600 to only a fraction of the affected workers and their families. The black workers received substantially less than their white counterparts.

Soon after the project wrapped, the workers’ shacks were torn down and a country club built to serve Union Carbide’s employees. A state park was established at the site in the mid-1930s, and the Civilian Conservation Corps built a charming stone overlook at what has become one of the most misunderstood and most photographed vistas in the state: the New River, dammed and pooling above the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel. Historical memory of the event has since then constituted nothing short of amnesia. Despite its status as the country’s “greatest” industrial disaster, it remains relatively unknown outside of West Virginia, and even here the incident is barely understood and seldom examined. It took fifty years for the state to mark the deaths at the site. The governor who presided over the disaster’s aftermath, Homer Adams Holt, who went on to serve as Union Carbide’s general counsel, excised the story from the WPA’s narrative West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State. Many also believe that when a novel based on Hawk’s Nest was published in 1941, Union Carbide convinced Doubleday to pull and destroy all copies.

The word “disaster” emerged from an era when people often aligned fortunes with positions of planetary bodies. It joins the reversing force, “dis-,” with the noun for “star.” As in, an “ill-fated” misfortune. If a disaster is an imploding star, then the rebirth of a star is its antonym. Recovery is a process of reconstitution—of worldly possessions, of wits. It is never complete. Not today, in the aftermath of June’s floods, and not in 1930. Eight decades on, West Virginia hasn’t recovered from Hawk’s Nest. How could it?—when so much of what was lost still hasn’t been named.

An abandoned rail line toward Vanetta, where tunnel workers once lived.

An abandoned rail line toward Vanetta, where tunnel workers once lived.

Now the photographer unpacks camera and case, / surveying the deep country, follows discovery / viewing on groundglass an inverted image.

I’ll admit I’ve got a thing about falling in love with dead women writers and chasing their ghosts around West Virginia. So when I found out Muriel Rukeyser, an American poet well known for both her activism and her documentary instincts, had visited and written a famous poem about Hawk’s Nest, I had to know more. Rukeyser was born on the eve of World War I to a well-to-do Jewish family whose heroes, she wrote, were “the Yankee baseball team, the Republican party, and the men who build New York City.” Her father co-owned a sand quarry but lost his wealth in the 1929 stock market crash. Until then, it had been a life of brownstones, boardwalks, and chauffeurs. As a girl, she had collected rare stamps with the heads of Bolsheviks and read like mad; slowly, over the course of her childhood, she awakened to what the comforts of her life may have signified in the world.

At twenty-three, Rukeyser found out about the nightmare unfolding in Fayette County from the radical magazines she read, and for which she wrote. After New Masses broke the Hawk’s Nest story nationally in 1935, it became the cause célèbre of the New York left. The house labor subcommittee began a hearing on the incident the following January. For a couple of weeks, the country absorbed the event’s gruesome details in mainstream media, but the federal government never took up a full investigation, despite the subcommittee’s urging. So early in the spring of 1936, Rukeyser and her photographer friend, a petite blonde named Nancy Naumburg, loaded up a car with their equipment and drove from New York to Gauley Bridge to conduct an investigation of their own. I imagine Muriel, fresh from winning the Yale Younger Poets Prize for her first book, Theory of Flight, in a smart, fitted blazer and a sensible skirt, glad to take the wheel from Nancy, especially on those curvy roads through the mountains. Their trip would form the foundation of Rukeyser’s poem cycle “The Book of the Dead,” included in her groundbreaking 1938 collection of documentary poems of witness, U.S. 1.

The women originally planned to publish their photographs and text side by side, but for unknown reasons their collaboration never materialized. The method was in vogue at the time, as writers and artists across the country—mostly white—dispatched themselves to document the social ills of the Great Depression in language and film. That same summer of 1936, Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell traveled from South Carolina to Arkansas, bearing witness to the Depression’s effects on rural communities for what would become You Have Seen Their Faces. James Agee and Walker Evans were also traveling, witnessing sharecropper poverty in Alabama for what would become the most famous of these texts, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The American road guide, as a genre, was also coming into its own. The federal government assigned teams of unemployed writers to turn their ethnographic gaze to the country’s landscape and social history, producing the American Guide Series, which aspired to become “the complete, standard, authoritative work on the United States as a whole and of every part of it.” The Federal Writers’ Project published its first in the Highway Route Guide series, U.S. One: Maine to Florida, the same year that Rukeyser released her own U.S. 1. “Local images have one kind of reality,” she wrote in the endnotes to “The Book of the Dead.” “U.S. 1 will, I hope, have that kind and another too. Poetry can extend the document.”

Much of what I know about Rukeyser’s life during this period comes, strangely enough, from a 118-page redacted chronicle of her activities, composed by the FBI. In 1943, J. Edgar Hoover authorized his agency to spy on the poet as part of a probe to uncover Russian spies; her “Communistic tendencies” placed her under suspicion of being a “concealed Communist.” When the investigation began, she was noted as thirty, “dark,” “heavy,” with “gray” eyes. In 1933, the report reads, she and some friends drove from New York to Alabama to witness the Scottsboro trial. When local police found them talking to black reporters and holding flyers for a “negro student conference,” the police accused the group of “inciting the negroes to insurrections.” Then, in the summer of 1936, after her trip to Gauley Bridge, Rukeyser traveled to Spain to report on Barcelona’s antifascist People’s Olympiad. In the process, she observed the first days of the Spanish Civil War from a train, before evacuating by ship. Her suspicious activities in the 1950s included her appeal for world peace and her civil rights zeal. The FBI mentions “The Book of the Dead” only once, in passing, as a work that dealt with “the industrial disintegration of the peoples in a West Virginia village riddled with silicosis.”

Its twenty poems recount the events at Hawk’s Nest through slightly edited fragments of victims’ congressional testimony, lyric verse, and flashes from Rukeyser’s trip south. She lifted her title from a collection of spells assembled to assist the ancient Egyptian dead as they overcame the chaos of the netherworld—“that which does not exist”—so they could be reborn. One of these texts, which concerns the survival of the heart after death, was carved onto the back of an amulet called the Heart Scarab of Hatnefer, a gold-chained stone beetle pendant that the Metropolitan Museum of Art excavated from a tomb and put on display in New York in 1936, the same year Rukeyser began her version of “The Book of the Dead.”

Curious to learn more about Rukeyser’s time in West Virginia, I called up a scholar named Tim Dayton, who had searched the poet’s papers for clues about the poem’s composition. He told me that Naumburg’s glass plate negatives of Gauley Bridge have since been lost, and that Rukeyser’s research notes were missing. The only evidence of their journey, I learned, consisted of a letter, a map, and Rukeyser’s treatment for a film called “Gauley Bridge,” published in the summer 1940 issue of Films, but never produced.

In the letter dated April 6, 1937, Naum-burg offered Rukeyser her “personal reactions to Gauley Bridge” and suggested a general outline for the piece. The document provides some clues about whom the women spoke to and what they saw—a few names, a vignette or two, and a description of the “miserable conditions” of those living with silicosis. “Show how the tunnel itself is a splendid thing to look at, but a terrible thing to contemplate,” Nancy wrote to her friend. Show “how the whole thing is a terrible indictment of capitalism.” She signed off, “Are you going to the modern museum showing tomorrow nite?”

The map of “Gauley Bridge & Environs” is signed by Rukeyser and drawn in her hand. At the center is the confluence of the New and Gauley rivers, where they form the Kanawha. Off to the side she sketched their little car, its headlights beaming forward. In cartoonish simplicity, she outlined the shapes that I recognize from my daily life: the trees, the bridge, Route 60. But some of her markings held greater mystery: a long, winding road jutting back into the mountains labeled, as best I could make out, “Nincompoop’s Road”; a house that was “Mrs. Jones’.” Rukeyser marked a big X on the town of Gauley Bridge, and an X over Alloy, rendered as a boxy factory belching smoke. She drew clusters of Xs next to two towns I’d never heard of on the Gauley River: Vanetta and Gamoca. This tracing of my home in her hand held the promise of a new way of knowing Hawk’s Nest.

I gradually came to see that “The Book of the Dead” is itself a kind of map. (So much so that a literary critic, Catherine Gander, convincingly argues for the text to be read as a rhizomatic map in the spirit of Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus.) Not only do the poems’ titles quite literally refer to people’s names and elements of the landscape—“The Road” or “The Face of the Dam: Vivian Jones”—the sequence also sketches out a crucial yet missing piece of the official Hawk’s Nest story, a narrative thread usually so common in the media’s treatment of disaster that it’s become a trope: the “pulling together of community.” Six poems in, we meet the Gauley Bridge Committee, an organized group of ten tunnel victims, their family members, and witnesses, whose caretaking and advocacy role had been totally absent from anything I’d read about the crisis up to that point.

Rukeyser introduces them in “Praise of the Committee.” They sit around a stove under a single bare bulb, in the back of a shoe repair shop in Gauley Bridge, amid the din of machine belts. They are: Mrs. Leek (cook for the bus cafeteria); Mrs. Jones (three lost sons, husband sick); George Robinson (leader and voice); four other black workers (three drills, one camp-boy); Mearl Blankenship (the thin friendly man); Peyton (the engineer); Juanita (absent, the one outsider member).

The room is packed with tunnel workers and their wives, waiting. The Committee’s purpose is to feed and clothe the sick and lobby for legislation. George Robinson calls the meeting to order. They discuss the ongoing lawsuits, a bill under consideration, the relief situation. They talk about Fayette County Sheriff C. A. Conley, owner of the hotel in town, who heads up “the town ring.” Rumor has it that he’s intercepting parcels of money and clothing at the post office, sent by well-meaning New Yorkers to tunnel victims. At the end of the poem, their spectral voices rise up like the chorus from a classical tragedy, asking: Who runs through electric wires? Who speaks down every road?

This scene played over and over in my head like the beginning of a film I wanted to believe existed about Hawk’s Nest. A film like the one Muriel meant to make, a story of dignity and resistance that was yet to be told.

Touch West Virginia where // the Midland Trail leaves the Virginia furnace, / iron Clifton Forge, Covington iron, goes down / into the wealthy valley, resorts, the chalk hotel. // Pillars and fairway; spa; White Sulphur Springs.

In the early Appalachian spring of this year—what proved to be the wet eve of June’s storms—I found myself barreling down Route 60 with “The Book of the Dead” in the passenger’s seat. The rivers swelled brown and bristled with snags of trees beneath color-drained mountains capped with a dusting of snow. I was following Rukeyser’s map, becoming a tourist in my own home. Along the road I saw metal buildings printed with soda pop logos and heard the shrieks of peepers in their vernal ponds. Easter loomed, and a church’s sign assured me: DEATH IS DEFEATED. VICTORY IS WON.

First stop: the “wealthy valley” from the cycle’s opening poem, White Sulphur Springs. It began as a resort hotel, marketing the area’s geothermal springs and relative freedom from insect-borne disease to slaveholding autocrats across the South, who evacuated their families from the lowlands each summer. The hotel was known then as the Old White—a string of cottages encircling a bathhouse, where the South’s antebellum politics and fashions played out around a burble of sulfurous waters with allegedly curative properties. Later owners the C&O Railroad changed the name to the Greenbrier. Though the sickly smelling spring was capped in the 1980s, the hotel is still run as a resort with a casino by West Virginia’s current Democratic nominee for governor, the coal operator Jim Justice.

Whenever I catch sight of the Greenbrier, there’s an initial moment of nausea. Like standing in the center of a vast array of radio telescopes or driving up a holler surrounded by a massive but out-of-sight surface mine. When Rukeyser drove through, the hotel’s stark white façade had just been redone, but the inside was still Edwardian and dim, draped in the depressing purples and greens of a deep bruise. Global merchant powerhouses like the du Ponts and the Astors would have been flying into the brand-new airport for the hotel’s famous Easter celebration, where princesses, movie stars, and politicians performed their circus of white gentility.

I parked beside a utility van brimming with roses and entered the building’s interior galleries, which glowed like Jell-O–colored jewels. A dramatically lit hallway displayed busts of what appeared to be the same white man carved over and over in alabaster. I watched as workers prepared for daily tea service by putting out plates of sweets, around which tourists swarmed like wasps. A cheeky pianist played the theme song to Downton Abbey as I grabbed a cookie and made my way back outside. I wandered down Main Street to Route 60 American Grill and Bar, where a man from Jamaica was beating a man from Egypt at pool. The bartender answered the ringing phone: “Route 60, may I help you?” Some chunks of something slid into the fryer. I played “I Saw the Light” on the jukebox and drank by myself, before heading off to sleep in my car at the Amtrak station, a redbrick cottage perpetually decorated for Christmas. The entire town of White Sulphur Springs would in a few months be under floodwaters; three bodies would be pulled from the resort grounds, where the five golf courses had, in a handful of hours, become a lake.

The next morning, I continued along the path Rukeyser laid out in her poem “The Road,” rolling westward through the Little Levels of the Greenbrier Valley, passing limestone quarries and white farmhouses drifting in pools of new, raw grass. In Rainelle, I stopped at Alfredo’s to eat an eggplant sandwich in a room full of steelworkers talking about ramps, the garlicky onion that heralds our spring. After, I skirted the mangled guardrails of Sewell Mountain, a 3,200-foot summit that today is clear-cut by loggers, where Gen. Robert E. Lee once headquartered himself under a sugar maple in the fall of 1861. I passed Spy Rock, where Native Americans sent up signal fires, watched for their enemies. New beech leaves glistered like barely hardened films.

In the afternoon I arrived at the Reconstruction-era courthouse in Fayetteville, less than a mile from my home, and climbed its entrance of pink sandstone. Most tunnel-related court documents were turned over to Rinehart & Dennis as part of the 1933 settlement deal. Even so, I found overlooked summonses, pleas, and depositions scattered throughout the county’s hundreds of case files. Soon, I held a blueprint of the tunnel in my hands, apparently entered as an exhibit in the first case to go to trial. It suggested the elegance of a graphic musical score, yet filled me with that stony disaster dread. At the time of the trial, some of the plaintiff’s witnesses were actively dying. Still, the jury deadlocked, and accusations of jury tampering arose when one juror was observed traveling to and from the courthouse in a company car. In time, the plaintiff’s lawyers were on record for having accepted a secret payment of $20,000 from Rinehart & Dennis to grease the wheels for a settlement. (In a turn of unexpected, though slight, justice, half the money was later distributed among their clients, by judge’s order.)

As I sat in the clerk’s office trying to put the pieces together, Fayette County Circuit Judge John Hatcher walked in. I was surprised when he stopped to talk. We traded wisecracks back and forth for a while, and then I showed him what I was looking at. “Awful what happened,” Hatcher said. “They killed a lot of blacks.” Then he launched into a story from World War II in which the American GIs give out chocolate bars to the survivors of a concentration camp, but the richness of the sweets makes their starving bodies sick. I wasn’t sure what the point of his story was until he looked me square in the eyes and said: “Nazis.”

The cemetery at Whippoorwill.

The cemetery at Whippoorwill.

I am a Married Man and have a family. God / knows if they can do anything for me / it will be appreciated / if you can do anything for me / let me know soon

I left Fayetteville and followed Route 60 over Gauley Mountain, crossing the tunnel’s path three times. I came into Gauley Bridge, the first community off the mountain and the first one you come to on Rukeyser’s map. It’s equal parts bucolic river town and postindustrial shell. I stopped at a thrift store, one of the only open businesses in the downtown core, and bought a copy of Conley and Stutler’s West Virginia Yesterday and Today for thirty-five cents. Adopted officially into the public school curriculum in 1958 but used widely in classrooms since its publication in 1931, it’s literally a textbook case of white people’s amnesia. The index does not list “Slavery.” The existence of “Negroes” is acknowledged six times, most often in relation to their “education.” It’s mute on the lost lives at Hawk’s Nest, offering instead a description of an engineering marvel and a scenic overlook.

Back out on the street, I heard a sweet voice call out: “Diamond, are you working today?” I looked up and saw a frail man with pale blue eyes, rubbing his nose with a tissue. I told him I was Catherine but that I wished my name were Diamond, and he said, “You favor her. She just started working down at the nursing home.”

He turned out to be Pastor Charles Blankenship, the preacher at Brownsville Holiness Church and the proprietor of the New River Lodge, formerly the Conley Hotel, where I planned to stay the night. What looked to me now like three shabby stories of grayish-yellow brick was a swanky stop for travelers when it was built in 1932, something I could imagine on the backstreets of Miami Beach. I believed Charles when he told me that Hank Williams had stayed at the Conley on many occasions. There’s strong evidence that Rukeyser had stayed here too; her son Bill remembers a black-and-white postcard of it among her keepsakes.

In 2016, I found the lobby a friendly clutter of dusty MoonPies, hurricane lamps, and old panoramic photos that lit up for me the Gauley Bridge of 1936: its busy bus station and café, its theater and filling stations, the scenes of prior floods. A bulletin board displayed one of those optical illusions of Jesus with his eyes closed—stare at it long enough (i.e., believe), and his eyes are supposed to open. Most of the hotel’s residents today are long-term tenants, elderly or on housing assistance, but this lobby used to hum, Charles told me, recalling the thick steaks that fried on the grill at the restaurant. The Conley filled up most nights when Charles’s dad worked here as a porter, hauling luggage to the rooms of rich people passing through on their way to the East Coast. “I can picture them coming through the door,” Charles said. “He used to get calls all night.”

Charles was born in 1939 and grew up in a company house in a nearby coal camp called Big Creek, located about where Rukeyser drew “Nincompoop’s Road” on her map. Like everyone I would meet, he wanted to know what I was doing in Gauley Bridge, so I told him I was looking into Hawk’s Nest and Rukeyser’s poem. He said he preached a funeral a few years ago for a woman whose daddy died of silicosis in the tunnel. He mentioned this fact in his sermon, and after the service, some of the woman’s relatives came up and thanked him. They hadn’t known.

I suddenly thought of the cycle’s poem titled “Mearl Blankenship,” about a “thin friendly man” who worked on the tunnel and served on the Gauley Bridge Committee. I asked Charles whether he had any relatives by that name. “That was my daddy,” he said. I told him about Nancy’s letter to Muriel, in which she wrote, “Stress, through the stor[y] of Blankenship . . . the necessity of a thorough investigation in order to indict the Co., its lawyers and doctors and undertaker, how the company cheated these menout [sic] of their lives.”

“Well, what about that?” said Charles with wonder. “He possibly did. . . .” He told me that his dad, whose nickname was Windy, had died at the age of forty-one. “He took that heart attack right over there,” Charles said, gesturing toward some couches in the lobby. That night his father had told Sheriff Conley, the hotel owner, over and over: “I’m hurting so bad in my chest.” Through the night, Conley fed him an entire bottle of aspirin pills. By the time he was rushed to a medical clinic around 2 A.M., Mearl had just hours to live.

I read “Mearl Blankenship” to Charles. Most of it consists of a letter that “Mearl,” a steel nipper who laid track in the tunnel, wrote to a newspaper in the city about his condition. At that point, he was losing weight and feared the worst. When I got through reading the poem, Charles said: “That wouldn’t be my dad. He never worked like that over there.” I asked him who he thought the guy in the poem was, and he said he didn’t have a clue. “It’s very unusual because all the Blankenships I knew.” He asked me for a photocopy, and then we discussed the brand-new aorta he got for free from a hospital in Cleveland.

That evening, I attended Charles’s church with a friend. The sanctuary of Brownsville Holiness, perched on a pitched hillside along the Gauley River, is adorned with red wall-to-wall carpet and a single, simple wooden cross. Services kicked off with an hour’s worth of live karaoke for the Lord, as congregants took turns singing at the altar, backed by members of a band who arrived late and casually set up around them. Then they all prayed in tongues. After, Charles shouted, “To know Christ is like coming out of a dark tunnel into the light! There is power in the blood of the Lamb! In the city where the Lamb is the light, you won’t need no electric there!” On multiple occasions, he stopped the service cold and asked both my Jewish companion and myself to approach the altar and give witness. I smiled with a Presbyterian’s customary politeness and declined. “Maybe next time,” said my good-natured friend.

Brother Nathan, with his thin, tawny hair and slow, easy voice, rose to read a scene from scripture. Simon and the other disciples were gathering up their fishing nets after nary a nibble all night, just as Jesus told them to throw the nets back out again, for no apparent reason. “Nevertheless,” said Simon, “at thy word I will let down the net.” Brother Nathan told us, “The facts will scare you. We need to put aside the facts. It’s time to say, ‘Nevertheless.’ I don’t care what the enemy throws at me. The devil can come at me every which way, but nevertheless, I’m going on with God, I’m going on with God, and I’m going all the way. . . . Nevertheless, nevertheless, nevertheless . . .”

Weeks later, I still wished I’d gone to the altar, that I’d known the right words about the tunnel to take there. Instead, I pieced together a Mearl Blankenship from census records—a white baby born “Orin M” in 1908 in the lumber company camp called Swiss. Ten years later, the family was farming; in 1930, “Murrell” was twenty-one and literate, living with his parents in the Falls district of Fayette among coal miners, dam construction laborers, painters, lumber ticks, and dairy farmers. By 1940, ten years after tunnel construction began, “Myal” was an unemployed cement mixer, married to Clara, with whom he had three children, including an infant, Charles. He worked only twenty weeks in 1939 and earned $800. He died of a heart attack on February 3, 1950, and was buried at Line Creek. Charles was ten years old.

I brought a copy of “Mearl Blankenship” back to the Conley on a cold spring day several weeks after my initial visit to Gauley Bridge—“a rough old day,” as Pastor Charles put it. I found him eating cheese puffs out of a coffee filter in the dim hotel lobby. He welcomed me back, took the poem, and this time read it to himself silently. He finally looked up, tearful, and said, “I’d say that was my Dad. I had no idea. It stands to reason he worked there, because there was no other work back then.”

What Charles remembered of his father was his sleeping body glimpsed through the doorway of their coal camp house. Light filtered through some kind of sheer curtain. Once, Charles watched a black snake slither out of the ceiling and dangle in midair over Mearl as he slept. Charles repeated the story about Sheriff Conley and the bottle of aspirin. He repeated the story about the family who didn’t know that their kin worked at Hawk’s Nest. When I finally got up to leave, he held my hand tight, locked into my gaze, and told me that he loved me. I told him I loved him back.

George Robinson holds all their strength together: / To fight the companies to make somehow a future. // “At any rate, it is inadvisable to keep a community of dying / persons intact.”

While reporting this story, I learned that two of Nancy Naumburg’s photos from Gauley Bridge had resurfaced at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The first is a shot of a town where black tunnel workers lived, Vanetta, which Rukeyser had marked with a cluster of Xs on her map. Raw wood structures line a thin strip of land between the railroad and the Gauley River. The air holds fog—or is it smoke? A scatter of people sits waiting for a train in the distance, where the tracks vanish into perspective.

After my first night at the Conley, I woke early and started down the abandoned rail line toward Vanetta. The cool, misty air sang with the frenzy of mating frogs and feeding birds. A dripping rock wall rose up on my right; wild blue phlox, oyster mushrooms, and sandy beaches spread down to the river on my left. After crossing a trestle, I began to pass into the frame of Nancy’s photograph.

It was the same bend in the track that Leon Brewer, a statistician with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, rounded in 1934. The apocalyptic dispatch he filed in confidence soon afterward counted 101 residents of Vanetta, occupying “41 tumble-down hovels, [with] 14 children, 44 adult females, and 43 adult males.” All but ten of the men were sick. “Support for the community comes from the earnings of 15 of the males, 14 of whom suffer from silicosis. Thirteen are engaged on a road construction project 18 miles away and are forced to walk to and from work, leaving them but 5 hours a day for labor. Moreover many . . . are frequently too weak to lift a sledge hammer.”

According to Brewer, these black families froze through the winter, starved and begged for both food and work. (One white local told me that he used to hunt for duck in the area where some of the sick, hungry workers camped on flat rocks next to the river; once, they asked him to bring them back a duck, and instead he returned with crow as a joke.) Brewer called for direct relief, “despite the protests of the white people,” and an immediate improvement in housing and sanitation. He declared that anyone who wanted to return home should be given passage and assistance with reconnecting to his or her home community. “At any rate,” he wrote, “it is inadvisable socially to keep a community of dying persons intact. Every means should be exerted to move these families, so that they may be in communities where they will be accepted, and where the wives and children will find adjustment easier.”

The other Naumburg image that resurfaced depicts the interior of a worker’s home in Vanetta: George Robinson’s kitchen. Robinson, who came from Georgia, was the closest thing to a media spokesperson that the black tunnel worker ever had. In the frame of the photo, light falls onto a cookstove with kettles at the ready, the papered-over wall of Robinson’s board-and-batten home arrayed with essential cooking implements: a whisk, a muffin tin, a roasting pan. A white rag dries on a line in the light.

I conjure the scene in the shack. I see George sitting, reciting what he told Congress and the juries, almost rote by now. His breathing is labored. I see his wife, Mary—is she distracted by thoughts of dinner, whether she should offer these women something to eat? Has a white lady ever been in her kitchen? Maybe they reminded her of the social workers who came from Gauley Bridge. Maybe Nancy is setting up her camera, her head ducking under the black cloth, as she peers through the ground glass, trying to get the focus right. Why, Mary wonders, had she chosen that wall? What did she read there? Did Mary want it to be read? Muriel sits, jotting down what George tells her in a notebook, wanting to capture it all, but also attempting to maintain eye contact—aware at every moment of the discomfort her privilege brings into the room. Was theirs a welcome visit, I wonder, or did the presence of these two white women disrupt the family’s hard-won and precarious sense of sanctuary?

Muriel and Nancy made this visit in the spring that followed Robinson’s congressional testimony; by June he was in the hospital, and by July 1 he was dead of “Heart Trouble” at fifty-one. On July 12, they buried him at Vanetta. I never found George Robinson on any census, nor do I know if he had children, or where I might begin to search for any surviving relatives. The only picture of him I ever came across was an Acme press photo from the D.C. hearing in which he is misidentified in the caption as “Arthur” (for that matter, his last name was misspelled in the congressional record). He sits at a table with papers spread around him, wearing a plaid woolen coat and button-up shirt. His arm is raised mid-gesture and his mouth paused mid-speech as he describes to the labor subcommittee chair the conditions under which he worked and contracted silicosis.

Robinson testified that he ran a sinker drill straight down into the rock, that it was operated dry, and that he wasn’t given any protective gear. He witnessed two men crushed by falling rock. “The boss was always telling us to ‘hurry, hurry, hurry.’” He described the dusty trees in the labor camps where black workers lived around the tunnel mouth, the shack rousters paid by the company to physically coerce the sick men to work. Sheriff Conley came around and ran off those who couldn’t continue, he said, men so weak they had to “stand up at the sides of trees to hold themselves up.” He remembered one who died under a rock. Robinson knew of one hundred and eighteen who perished, had personally helped bury thirty-five, and estimated a total death toll of five hundred. He said the company burned down the camps when the project was complete, so the workers would scatter. They even “put some of the men in jail because they wouldn’t vacate the houses.”

Bernard Jones—a white man who lost his father, uncle, and three brothers to silicosis—gave new context to this exodus story in a 1984 oral history with occupational health specialist Dr. Martin Cherniack. The white merchants at Gauley Bridge had liked the idea of the tunnel workers at first, said Jones, because they thought money was to be made from them. But eventually, they got “irritated” and accused them of “thieving,” stockpiling stolen goods under a nearby railroad bridge. The merchants and professionals wrote an open letter denouncing the media for printing “propaganda” about their town, decrying the “undesirables, mainly Negroes” who had taken up residence there. Still, some of the black workers who lacked either the health or the means to go elsewhere attempted to stay at Vanetta. “Who it was I do not know,” said Bernard, “but somebody in Gauley Bridge went across the river in Vanetta, and they put a big cross up there on the hillside and wrapped it with rags and soaked it with gasoline and set it on fire. Well, these black people, when they seen that cross burning, that scared them. And the next morning one group right after another came down that railroad track headed for the bus station, going back home to the South.”

And now here I was, the latest white witness-invader, tromping in the opposite direction, back into Vanetta, where not a single structure was left. I saw a path that led from the tracks up the hillside and into the woods. Rukeyser’s poem “George Robinson: Blues” tells me to look to the hills for the graveyard, and so I followed its lines into what was becoming a warm, cloudless spring day. I found it: a cemetery covering the whole mountain. I saw a corroded gravestone from 1865 and the fresh grave of an infant buried the day before, but I never found George Robinson’s.

He shall not be diminished, never; / I shall give a mouth to my son.

In press photos and newsreels from 1936, Emma Jones appeared white, beautiful, and hungry. Sometimes she wore a little fur around her neck. She—who had lost three sons and was soon to lose both her brother and her husband—had become the white face of the tunnel’s suffering in the American mind, the media’s “Migrant Mother” of this particular disaster.

When construction began, she and her husband, Charley, lived at Gamoca (Jah-MO-kah), a little town with a company store and a swinging bridge over the river, just down the tracks from Vanetta. She had nine children at the time and would go on to have two more. Charley and her sons worked in the coal mines, when there was work (which there wasn’t). That is to say, they bootlegged. It was one of Charley’s customers, a foreman at the tunnel, who convinced them to look for jobs at Hawk’s Nest. Charley became a water boy. Cecil, the oldest son, was a driller. The youngest, Shirley, a nipper. And Owen, the middle son, had a mean streak and disliked blacks, so the company supervisors made him a foreman and gave him a ball bat.

The brothers got sick around the same time; their father held out a few years longer. Emma went out to Route 60 and begged for money to buy them chest X-rays. Before Shirley died—so skeletal Emma could lift and move him around the house like a lamp—he made his mother promise to have the family doctor perform an autopsy on his body. The doctor, in fact, preserved the lungs of all three brothers, hardened like cement, in jars as proof of their disease. The Jones Boys. That’s what the doctor’s son and his wife called the disembodied lungs after the old doctor died, I guess to make the whole thing feel less atrocious. The lungs sat in the couple’s basement for years like forgotten pickles—until they loaded them into the back of their pickup truck, drove them up to the dump at the top of Cotton Hill Mountain, and chucked them over the side. “They sure made a racket when they went down over the mountain,” the woman said later in an oral history, “but it sounded like just one jar broke.”

I learned that many of the family’s descendants still lived in the area. People like Anita Jones Cecil, one of Charley and Emma’s grandchildren. I hesitated before contacting her, worried that I would disrupt her grieving process, or that she wouldn’t want to talk to me; worse yet, that she’d want me to stop talking. But when I found her on Facebook one day, it seemed like maybe she’d been waiting awhile to tell this story. “My family is chained to that place by ghosts,” she wrote in the message box. “Hawk’s Nest chained my grandmother and my father to Fayette County through generational poverty. . . . I have three sisters and two brothers, and I am the only one that went to college. We didn’t have a chance.”

Anita agreed to meet up at the library in downtown Charleston, where we settled next to a window in a dim, empty meeting room. She struck me as graceful and strong, with long brown hair and brown eyes, deep dimples, and a gaze that felt like a steady hand. She said, “This is what my dad told me, and what I actually think: they actively sought people who were poor, who were desperate and uneducated, and shipped them up here. Expendable people. People that nobody would miss.”

Together, we looked at Rukeyser’s map. I pointed out the house labeled “Mrs. Jones’.” Anita told me it was the small farm that Emma and Charley bought for $1,700 with their settlement money, near present-day Brownsville Holiness. They received roughly twice the compensation that a black family would have received, but there was still nothing left over to live on, and Charley had to go back to work in the coal mines to pay off their debts. For a short time, while she was pregnant with Wilford (Anita’s father), Emma worked at a WPA sewing factory in Gauley Bridge to support the family. Her oldest surviving son later said that she gave away bags of potatoes and flour to needy neighbors until the money ran out, and the family was right back where they started.

Charley died in 1941, leaving Emma a single mother with three children under eighteen. Then their house burned down. Emma turned to the Holy Spirit to get her through those times—she prayed and spoke in tongues. Eventually, she remarried and settled in a four-room coal camp house in Jodie, and life got a little easier. She had one of the nicest homes in town, with red tar shingles, a little fishpond, and a colony of elephant ears that she grew and shared with her neighbors. Anita may have never met her grandmother, but she grew up in that house, raised by her grandmother’s ghost.

Anita said her father used to warn her not to depend on anybody else, not even a man, for anything. “You have to make it on your own”—that’s what the tunnel taught Wilford Jones. But Anita thought it taught him something else, too. “My dad was always going on and on about how you should treat everybody the same, everybody’s equal no matter what the race, religion, any of that kind of stuff. And I think that was directly related to his experiences as a little child.” Anita said her father was clever, could do math in his head. He started college but couldn’t figure out a way to pay for it, so he came home to help support the family. The only work he could find was in the coal mines, and by the time Anita was a child, he was sick with black lung. She told me it didn’t hold him back. Once, while he healed from heart surgery, “The miners went on strike, and he wanted to go out and picket with staples in his chest,” she said. “That’s the kind of people we’re dealing with when you talk about my family.” Near the end, perhaps delirious from lack of oxygen, Wilford got the idea that he was the actual son of Mother Jones, the union organizer who radicalized after she lost her four sons and husband to yellow fever. Some people had a theory that she had given her children up instead, to shield them from the dangers of her work. It became part of Wilford’s truth that he was one of those sacrificed sons. Before he died at the age of fifty-six, he told his family to open his chest when he was gone, just as they’d done to his brothers, to perform an autopsy and prove he had black lung. He told them to seek compensation. “I think he dwelled on the past and thought about how things should have been and was sad over it,” said Anita. “I personally, I’m a little bit mad.”

Anita channeled that rage into a career in social services—she became an economic service worker at the West Virginia Division of Rehabilitation Services, processing relief applications and determining eligibility for Social Security and SSI. When Anita drives past the Alloy plant today, she thinks, “That’s who killed my family. That’s where our lives went. . . . I watch it happen over and over again in West Virginia, where families of coal miners, families of Hawk’s Nest, will lose their primary breadwinner and they just struggle and struggle and struggle until they die.” After all the death, after all the wealth was shipped out of the tunnel, she said, nothing was ever given back to Gauley Bridge—no investment in education or infrastructure. “Instead of being developed, it died with those men.”

We read Rukeyser’s poem “Absalom” together, facing each other in two chairs before a window overlooking the main intersection of Charleston’s modest downtown. Somewhere in the shadows of the room, I like to think, Muriel was there—her wavy hair pushed back from her wide forehead, a dimple marking her soft chin. Anita held a photocopy of the poem in her hands, while I held the recorder. She leaned forward, reading half silently and half out loud lines from her grandmother’s congressional testimony, jump-cut with fragments of spells from The Egyptian Book of the Dead. When Anita got to lines that interested her, she stopped and free-associated.

One of these was a passage that Rukeyser appropriated from the ancient text, meant to ensure that the hearts of the deceased were given back to them before rebirth. Then the deceased get their mouths back, and their limbs stretch out with an electrical charge. They are reembodied, with the power to move between portals of worlds freely. “I will be in the sky . . .” the dead chant.

I asked Anita where she found hope in this story—her story, any of them—because sometimes I simply could not. She said, “Have you ever really looked at Gauley Mountain, how beautiful it is? That’s where I find my hope, yes. You think to yourself, God’s here. He’s here. He’s not forgotten any one of those souls that died.” She handed me a Bible verse she’d written out: “Fear not, therefore, for there is nothing covered that shall not be revealed; nothing hidden that shall not be known.”

“That’s what I think of when I think of Hawk’s Nest,” Anita said. “I’m not afraid. ’Cause I know everything will come out eventually.”

I take her to mean, “God knows what that company did.”

A few weeks later, I walked three-abreast on the train tracks with Anita and Rita Jones Hanshaw, Anita’s sister, toward Gamoca Cemetery, where most of the Jones family is buried. The day threatened rain; the Gauley flowed deep and brown in flood, though we were still months from the June storms that would bury Belva in water. The sisters debated the way up to the graves. Anita tore through the thickening understory in one direction, while Rita and I started up a rugged logging path. Both women found it at once: the array of bathtub-size depressions in the earth, clusters of metal markers nestled among saplings, with blank spaces where the names once were. Tree roots heaved up and twisted the iron fences encircling the burial plots. We came to a slight clearing, shaded by giant hemlock and carpeted in Easter lilies—there in a row, Shirley, Cecil, Owen, and Charley lay buried. A family member with money had recently invested in flat stone markers, engraved with their names. Emma’s body rests with her second family in nearby London, West Virginia.

Rita, the spitting image of her grandmother, spoke of her thirst for justice; of Shirley, who was working in the tunnel to save money for college; the thrill she felt a few years ago when she first heard the sound of her grandfather’s voice, caught in an old newsreel someone posted on YouTube. Around that time, she and her sister Tammy began digging in the archives for the death certificates of tunnel workers, as a kind of self-fashioned therapy. “We just feel that us doing the research, and finding out what happened, it helps us heal. I know it was before we were born, but we still have feelings about this. It’s our grandparents, people we didn’t get to know. And through this we feel like we’re growing to know them.”

For those given to voyages : these roads / discover gullies, invade, Where does it go now? / Now turn upstream twenty-five yards. Now road again. / Ask the man on the road. Saying, That cornfield?

The white cemeteries wouldn’t accept the growing number of black dead, and the slave graveyard at Summersville was already full. So Union Carbide paid an undertaker named H. C. White $55 for each tunnel worker he buried in a field on his mother’s farm in neighboring Nicholas County. In 1935, a photo of cornstalks and mass graves on the White Farm made its way into the mainstream press and eventually caught the concern of a congressman from New York, who called for an inquiry into the accusations of corporate criminality at Hawk’s Nest. Members of the Gauley Bridge Committee and others gave nine days’ worth of official testimony, but Congress never took up the labor subcommittee’s recommendation to investigate. (The West Virginia legislature passed a weak silicosis statute in 1935, essentially set up to protect employers from similar future disasters.) Nevertheless, a trove of eyewitness and victims’ accounts, which would have otherwise gone missing, had been put down on record. And without that, it’s hard to imagine Rukeyser’s “Book of the Dead”—or much of any memory at all.

The White family sold their farm in 1954, and the record remained more or less as it was until 1972. That year, the state surveyed for a new four-lane road and found human remains in its path, sixty-three possible graves. A state contractor sifted through the soil for bones and placed them in three-foot boxes, reburying them adjacent to the highway, along the towering pink sandstone cliffs that edge Summersville Lake. H. C. White’s son, the local undertaker of record, signed off on the whole thing. And there they remained, forgotten again, until 2012.

Thirty miles from Gamoca, at a highway exit called Whippoorwill, I met up with Charlotte Yeager, who played a role in the recent rediscovery of the Hawk’s Nest burials. I parked next to a guardrail strewn with the Weed-Eaten heads of wild daisies. Charlotte, the publisher of the Nicholas Chronicle, emerged from a gray minivan with a pin on her chest in the shape of a ramp. It was April, and Richwood (another town hit hard by the June floods) had just hosted its big feed.

Charlotte heard the rumors about the bodies of black workers buried in the hills when she moved from Charleston to Summersville twenty years ago. “Everybody knew it, you know. It was just kept hush-hush because they were embarrassed.” She tried a few times to locate them but with no luck. Then one day, she read a story in the Charleston paper about two guys—likewise haunted by the missing men—who had led a reporter to this site, claiming it held some of the workers’ graves. One of them, Richard Hartman, later told me that the first time he went to Whippoorwill, he had to pick his way over rusting appliances and piles of roadkill that the highway department had been tossing over the side of the road for years. The sun’s glint on a metal grave marker between the trees and trash was all that gave it away.

After that newspaper story, word got out, and a group of community members arose around a common desire to rededicate the cemetery. They included not only Charlotte, but local high school students, religious leaders, filmmakers, government officials, and descendants of white tunnel victims—like the Joneses. They cleared the area around the graves; the state came out and did a radar survey of the site. Rita Jones Hanshaw, a schoolteacher, and her sister Tammy began digging into vital records for names of workers. Plans for a memorial park were drawn up and then realized at a 2012 ceremony honoring the dead. A white barefoot preacher from Summersville joined with a black minister from Beckley to anoint the site with water from the New River; local youth lit a candle for each departed soul. It had taken eighty-two years, but hopes ran high that the workers’ families might be reunited with their loved ones across death.

Charlotte led me through an elegant archway, past a stone engraved with the story of Hawk’s Nest, and up a short path to several neat rows of depressions, each marked with a wooden cross and an orange surveyor’s flag. After days of rain, the depressions held clear, still water that reminded me of baptismal fonts in a church sanctuary. Hemlock, beech, and red maple saplings grew among and inside them; moss and ferns cushioned lichen-draped boulders forming natural benches around the burials. Sunlight dappled the glossy leaves of rhododendrons. It would have been almost peaceful if not for the rushing traffic above our heads. But it was beautiful, in spite of itself.

Later, as I sat in my car next to the creek that drained Whippoorwill into the lake, I thought with disgust: I swim here in the summer. Then I got a random call from a friend who had lost the hard drive that contained her life’s digital history, who sought my advice for its recovery. I told her that the thing about data is it’s not invisible; it’s there, in traces. Every byte has its physical form. Poetry, I remember thinking, fills in the gaps.

The hydroelectric station on the New River powered by water from the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel and Dam.

The hydroelectric station on the New River powered by water from the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel and Dam.

Defense is sight; widen the lens and see / standing over the land myths of identity, new signals, processes:

The Gauley Bridge Historical Society is headquartered in some shambles in a narrow green building on Route 60, next to a bridge that burned twice in the Civil War. I had heard that the old museum held documents relating to Hawk’s Nest, so I’d made an appointment to visit. It was raining when I walked in, and Nancy Taylor sat at a desk among empty display cases and stacks of files. She looked at me like the public school teacher she is and said, “How can I help you?” in a tone that sounded like, “Impress me.” I told her I’d come to see the material she mentioned on the phone, and she started handing me bundles of papers.

I took them to a table and began flipping through one of the stacks. I saw typewritten lists of names, mortality tables, narratives, and I felt the quickening of adrenaline through my blood. I started urgently taking photos for later study, but it soon became clear that the pages—which appeared to be multiple sections of a single text—were in jumbled disarray: faded legal-size photocopies of names, some barely legible, and hopelessly out of order. Under the tin roof in the rain, I spent hours of the afternoon reconstructing the document. Nancy seemed into it and said she didn’t have anything else to do. The chief of police even dropped by to add his two cents. What he said, I don’t remember. All I could think about was the sorting. Finally, I put the last of its two hundred and twenty-seven sheets into place, which turned out to be the title page: Accident and Mortality Data on Rinehart and Dennis Company Employees and Miscellaneous Data on Silicosis, Copy No. 2, March 10, 1936. Nancy and I cheered. She let me borrow the manuscript (I think she was grateful for the new order). I felt its preciousness in my hands, its presence in my car on the way to the copy shop.

When I finally read it, I could see it was the company’s version of everything—their racially segregated tallies of employees who died in West Virginia from 1930 to 1935 (one hundred ten total); their count of “alleged” silicosis victims (fourteen); their estimation of the number of men they admit actually died of the disease (basically none). Line by line, they rebutted the testimony of the Gauley Bridge Committee’s members, tearing into them with audaciously racist and belittling commentary, blaming the victims and “radical agitators” for all the trouble. Of their leader, George Robinson, they wrote that he was faking it all, in order to enjoy “notoriety, travel without cost to himself, and the pleasure of making an impression on white people for probably the first time.” One section included a list of the deceased for whom H. C. White had served as undertaker: sixty-one employees (fifty-six black, five white) and five camp followers, including three women. Thirty-six he buried at the White Farm; the remainder were placed in other local cemeteries or shipped out of state to towns like Syria, Virginia; Union, South Carolina; Knoxville, Tennessee. . . . This list was flawed and, like the congressional hearing, not enough, but it was a beginning.

It was the beginning of more than memory. I’d found the company’s narrative, yes, but it held the names, each one the beginning of a spell against the narrative of disaster. And against shame. Each one, a link to descendants for whom this list likely mattered a whole lot more than it did even to me. Here was the evidence one could intone. Like Rukeyser’s poem, the list ran counter to the version of events where we all crawl off and die quietly. It held the potential to move that story, and it had been sitting here this whole time.

How had it made its way into this halfway shut-down museum? Nancy casually mentioned the name of a mutual acquaintance of ours who might know more about its origins, so I called him up. “I got [those materials] in a way that I probably shouldn’t have,” he told me. “I’ll be real cryptic here. I was able to get into the rooms at the power station where they stored all the records, and I borrowed a lot of stuff one night, and I shared that with a number of folks. . . . And then I put the originals back.” This was back in the 1980s. Apparently, he said, the company had bought everything they could find about Hawk’s Nest and put it all in a room that “looked like a jail cell,” under the power house.

and this our region, // desire, field, beginning. Name and road, / communication to these many men, / as epilogue, seeds of unending love.

I used to be able to walk so close to the dam that I could practically climb across it. At its edge sat a creepy beige trailer with a single light that could be seen from the gorge’s rim at night. On a wet day in April, I set out for it; I wanted to see the dam as it strained against the spring rains. The river ran wicked under the bridge where I parked and then started down a gravel road thronged with red warning signs: EXTREME DANGER—IF YOU NOTICE CHANGING CONDITIONS, GET OUT!

I had pushed levers called questions and the story had opened. How unqualified, how unprepared I felt for what I had found. Until that day at the Gauley Bridge Historical Society, few words had adhered to the uncounted dead, so I could abstract them in the “supposed” or “alleged” past. Suddenly their scale had become specific, and therefore vast. I knew their families were out there, in my mind always somewhere south of here, living—either in full knowledge of their family’s inheritance, or in ignorance of it. Their trauma, I presumed, could be traced down through the generations. Yet none of this suffering was mine, was it? “Mine.” I feared I was reinforcing some kind of savior narrative I had about my own white self—a middle-class woman who just wanted to “do the right thing,” not embarrass anybody, most especially herself. I worried that, instead of resurrecting, I had desecrated the resting dead—ghosts who had never elected me their spokesperson. The names of the Hawk’s Nest dead gave me powers I wasn’t sure I deserved.

Birds of prey called from the Appalachian jungle, the purple bells of the paulownia trees rang out as I walked, listening for the dead. I turned to look behind me. I rattled my keys. What was I afraid of? The dam of history, bursting. I felt it cracking open, an inner chamber of the disaster that I hadn’t known existed. I was afraid—of the woods, of the story, of the names.

I saw that a new barbed-wire gate had gone up to stop public access to the top of the dam, so I headed down a trail toward the river’s edge, where waves dashed boulders like the starry backs of breaching whales. These are roads to take, Rukeyser wrote. I believed her. I took the roads. I thought of my country. And it had taken me to this terrible June, still looking to name what I’d found in the tunnel, for some cathartic shudder of light. The document has expanded, but into a longer list of undervalued, erased lives, as the rivers in West Virginia run their banks, as #WeAreOrlando and #BlackLivesMatter shout over and over to #SayTheirNames. Soon I will wake to #AltonSterling and #PhilandoCastile. Soon I will wake to Donald Trump’s nomination for president. The same white supremacy that allowed, condoned, and covered up the mass killing at Hawk’s Nest still asserts its dominance. The road of history is flooded with all of this, and so am I. But this is the road I must go down. It’s the only one we have. This is the disaster that it’s now our legacy to dismantle.

I drew closer to the water’s rush and caught a view of the dam through the trees. I stopped and stared, and as I lifted my camera to record, I swear I heard the dam’s steel gates groan. Those red signs flashed in my mind: KEEP AWAY! KEEP ALIVE! I ran scurrying back up the path. Circular clusters of fallen paulownia blossoms lit the way like lavender spotlights. With relief, I reached my car, and then I heard and felt a thunderous thump in the gorge behind me—something geological in scale fell. I thought of the blast from a surface mine, and then of my own beating heart.

Explore a partial list of employees of Rinehart & Dennis Company and camp followers who died in West Virginia, April 1, 1930 – December 31, 1935

This is a fraction of the Hawk’s Nest dead—almost certainly, other victims’ names were never recorded by the company, either because they died elsewhere or because their race meant they were written off. If disaster is the undoing of a star, then each of these names is a star being born.

For more information, visit HawksNestNames.org

Photographs by Lisa Elmaleh

Enjoy this story? Read "A Photographer's Daybook," for more of Lisa Elmaleh's photographs from the journey and subscribe to the Oxford American.