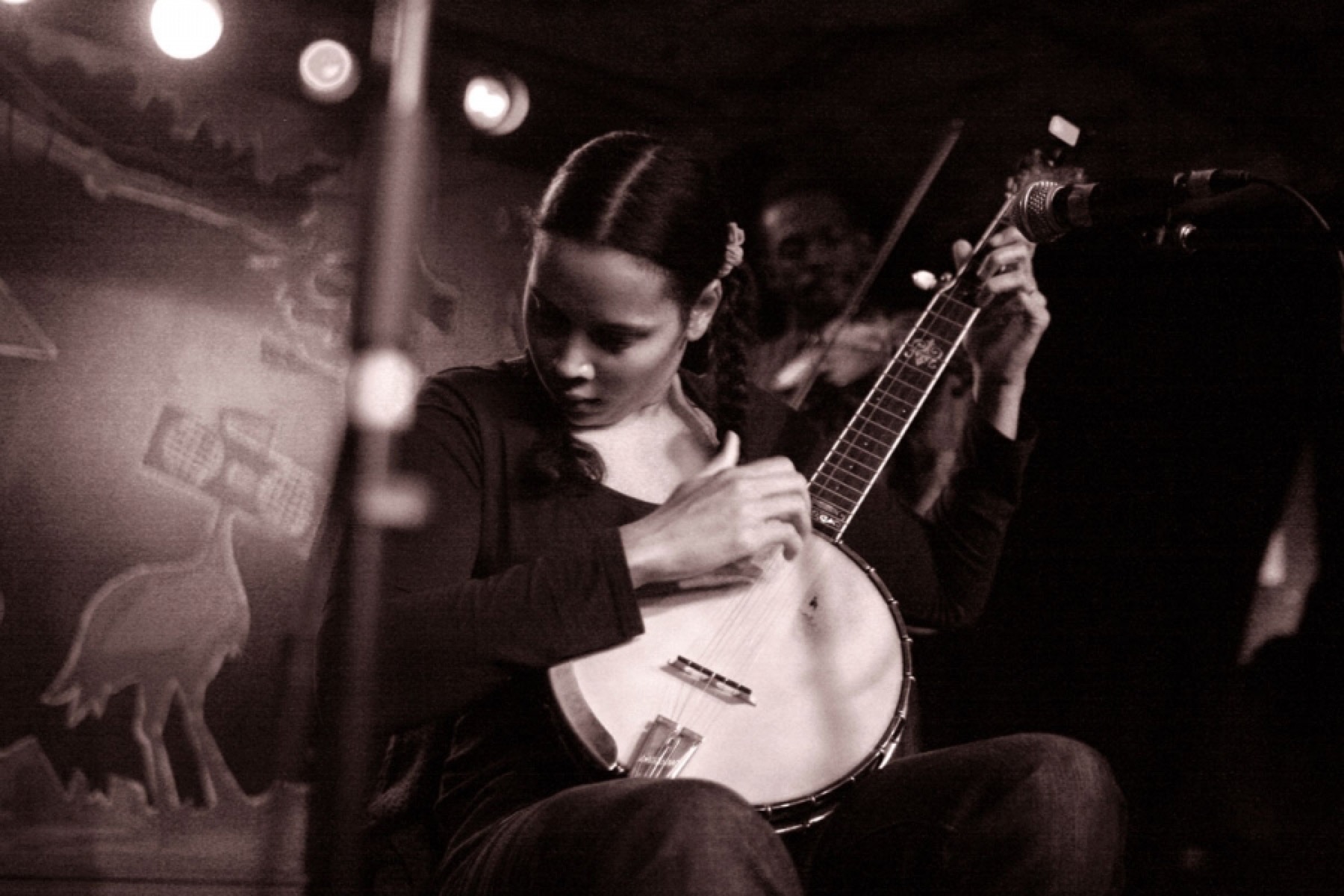

Photo of Rhiannon Giddens by Danielle Osfalg

Past Is Present

By Gayle Wald

Tucked away to the right of the main entrance to Lisner Auditorium, a boxy limestone building on the campus of the George Washington University, where I teach, is an unassuming metal bench. It was placed there in 2011 as part of the “Bench by the Road” project inspired by Toni Morrison. In 1988, in a short speech she gave upon accepting the Frederic G. Melcher Book Award for her novel Beloved, Morrison explained that she had been prompted to write her masterful meditation on American slavery in part to address its absence in U.S. cultural memory. “There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of, or recollect the absences of slaves,” Morrison observed. “There is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby. There is no three-hundred-foot tower. There’s no small bench by the road.”

Lisner’s Bench by the Road pays symbolic tribute to Morrison’s call for a “place” to remember the enslaved. It also stands as a reminder of the post-Emancipation legacies of racism. In the mid-1940s, when Lisner opened, black Washingtonians were prohibited from enjoying its commercial entertainments, from ballet and concert recitals to Ingrid Bergman’s star turn in Maxwell Anderson’s drama Joan of Lorraine. That began to change after protestors mounted a leafleting and boycotting campaign to force the university to reform its policies, which it did reluctantly. Not until 1954—the year of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation Supreme Court decision—was Lisner fully desegregated.

Last February, Morrison’s poignant conceptualization of art as a place of memory was in my mind when I went to the auditorium to watch Rhiannon Giddens perform with Bhi Bhiman and Leyla McCalla. The occasion was “Swimming in Dark Waters: Other Voices of the American Experience,” a Giddens-produced showcase of American protest music, from a Haitian folksong to a contemporary satire of the greed that brought about the cataclysmic 2008 housing bubble and Great Recession. Nowhere was the spirit of the Bench by the Road more present than when Giddens, accompanying herself on banjo, performed “Julie,” a song that narrates the conversation of an enslaved black woman and her white mistress as the two contemplate the approach of Union soldiers to the “Big House” of a Southern plantation. In the lyrics, the mistress seeks reassurance that Julie will remain by her side during the uncertain times ahead. Fearful that the soldiers will plunder her “trunk of gold,” she asks for Julie’s help in deceiving them. But while Julie vows to stay by her mistress’s side until the Northerners come, she also coolly reminds the white woman that “her” gold was acquired through the sale of Julie’s own children. It is blood money. And at first opportunity, Julie will depart—“with what family I have left”—from the site of misery that her mistress calls “home.”

With a banjo line that echoes the familiar folk ballad “Pretty Polly,” perhaps not incidentally another song about violence linked to women’s capacity for reproduction, Giddens’s “Julie” cast a powerful spell over the Lisner audience. When Julie informs her mistress that in leaving the plantation she is “leaving hell,” the auditorium roared its approval—and roared, too, I would like to think, at the injustice of many “hells,” including some in which we still find ourselves. At that moment, I could feel the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Here a diverse group of listeners had gathered in Lisner Auditorium, a historic site of antiracist struggle, to collectively reflect on the gendered violations of slavery while allowing ourselves to feel the echoes of the past in our current moment. In an act of what, following Beloved, we might call sonic “rememory,” Giddens invited the audience to reconnect with our painful national past. More than that, in channeling the character of Julie, she offered herself as the vessel for surfacing the traumas of slavery.

In a single song, Giddens’s performance exemplified both her prodigious talent and her clear-eyed conceptualization of music as history: not merely as sonic ornamentation of the past but the past in sonic form.

This has been a year of ups and downs for Giddens. Mostly ups. Early in 2016, “Swimming in Dark Waters,” her limited-run tour based on these radical ideas, generated both income and critical raves, and could have supported more tour dates had circumstances allowed. In spring, Giddens was cast as Audra McDonald’s replacement in the Tony Award–winning Broadway musical Shuffle Along (full title: Shuffle Along, or The Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed) and was well into rehearsals when, in late June, the producers abruptly canceled the show, deeming it commercially inviable without McDonald. Suddenly, Giddens’s stream of giddy social media postings about her preparations for her Broadway debut and experiences as a New York City newbie came to a screeching halt. (She tweeted: “My heart is broken. Completely and utterly.”) Within two weeks, she had cut her long hair in a shoulder-length bob and dyed it azure, dubbing her new ’do “Broadway Blues.” But the blues, like the hair paint, didn’t linger for long. In September, producers of the TV show Nashville announced that Giddens had been hired to play the recurring role of social worker Hanna Lee “Hallie” Jordan in its fifth season (which debuts January 5 on CMT). Days later, she was awarded the prestigious Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass, cited for her “unique position” as a performer who bridges “contemporary and traditional forms and the cultures of three continents.”

In person, Giddens exudes a fierce dedication to her craft and an equally fierce commitment to diverse forms of social justice. She talks as passionately about the sounds of nineteenth-century banjos as she does about the policing of black teenagers in North Carolina. Over a recent lunch in Manhattan, she explained that she sees herself as playing the role of a “historical musician,” someone who resurrects and enlivens forgotten or neglected traditions, sometimes in terms that pay homage to the old-time sounds and instruments, but as often with flourishes (such as beatboxing) that call upon the new. She is also, as in “Julie,” interested in using her music to enable audiences to engage emotionally, not just intellectually, with the past. She knows that “Julie” will make listeners cry because she shed tears when first performing it. But this is part of the musician’s gift. When you sing, as Giddens puts it, “your spirit—your soul, whatever you want to call it—is coming out of your mouth.”

Giddens took an unconventional path to get to the place where both Broadway and the country music industry would come a-courting. She discovered her musical calling serendipitously while studying vocal performance, with an emphasis on opera, at Oberlin Conservatory. On a whim, she attended a contra dance and discovered a living tradition of fiddle music. Although she had grown up in North Carolina, it wasn’t until after returning home from Ohio that Giddens came to fully appreciate the hybrid European, African, and Native musical traditions of the region that had produced her. To riff on a phrase of renowned Fisk University music professor John Work III, a man who deeply appreciated black folk traditions at a time when black elites preferred their spirituals in “concertized” form, there was “beautiful music all around,” Giddens felt, and in the very place where she herself had originated.

Giddens first gained public recognition as a founding member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, the Grammy Award–winning group with whom she toured and performed for eight years, resurrecting and improvising on a rich tradition of black string-band music in the United States. Her solo career took off in 2013 after her stunningly self-possessed performance as part of a concert at New York’s Town Hall inspired by the Joel and Ethan Coen film Inside Llewyn Davis. A relative unknown amid a cast of musical luminaries including Joan Baez, Elvis Costello, and Patti Smith, Giddens performed a fervent, blues-tinged version of “Waterboy,” the song made famous by Odetta during the 1960s folk revival, and then pivoted effortlessly to Gaelic mouth music, showcasing her vocal dexterity and fine sense of rhythm. T Bone Burnett, who produced the concert, stepped up with an offer to produce an album. The collaboration bore fruit in Tomorrow Is My Turn, released when Giddens was thirty-seven years old. Across ten recomposed covers (including “Waterboy”) and an original piece, the lilting “Angel City,” the 2015 album finds Giddens supported by a skilled cadre of studio musicians (including Burnett) and an equally gifted set of backup singers, including the legendary Táta Vega. It earned Giddens a Grammy nomination (for Best Folk Album) and a BBC Radio 2 Award (for Folk Singer of the Year). NPR music critic Ann Powers called it “a scrupulously selected, richly realized collection of songs spanning American music’s history of communal uplift, individual outcry, happy collaboration and profitable theft.” Factory Girl, a follow-up EP consisting of music recorded during the Tomorrow sessions, was released later the same year.

Tomorrow Is My Turn honors pioneering American women in music, from icons like Nina Simone, Dolly Parton, and Patsy Cline to recently rediscovered figures such as Rosetta Tharpe and Geeshie Wiley. Delving into blues, country, gospel, jazz, and more, Tomorrow is also a declaration of Giddens’s creative independence from servitude to musical labels, including “Celtic,” a term that can sometimes make her out to be a racial interloper, despite the demonstrable Irish lineage of North Carolina music, and “Americana,” which is often carelessly applied to acoustic music of any provenance. The eclectic repertoire of Tomorrow is not fully represented by the amorphous “folk” moniker, nor is it static homage, as the word folk sometimes suggests. Rather, through her selection and revision of songs, Giddens reimagines and reconstructs the archive of American music, drawing on the example of women who were similarly allergic to confinement by genre. The list of tracks reveals the sort of rich, heterogeneous assemblage that is anathema on a Spotify playlist. Meanwhile, the songs collectively tell a story about women who, while making their musical marks in diverse genres and in different historical periods, all traveled the distinctive “lonesome road” (to cite a song Tharpe popularized) of a musical career marked by deep ruts and potholes for women, especially black women. When I brought up the fact that most of the musical foremothers referenced on Tomorrow had eschewed motherhood (either by choice or of necessity), Giddens—who has two young children of her own and is married to the Irish musician Michael Laffan—talked openly about the challenges of reconciling music with domestic routine. When female musician-friends have asked her for advice on the matter, Giddens said that she cautions them to think carefully about what it means to try to raise kids while developing a career that demands not only travel, but time spent immersed in the work of making music.

Giddens’s take on the canon of twentieth-century American women’s musical performance has earned her accolades among young Beyoncé fans, who hear in her determined delivery of the title phrase “Tomorrow Is My Turn” an explicitly political imagining of black women’s power akin to what their pop idol has produced in her much lauded visual album Lemonade. For her part, Giddens cites a definitive performance by Nina Simone—another classically trained daughter of North Carolina—as the source for the energy that emanates from her reading of the English translation of Charles Aznavour’s suave composition (originally “L’Amour C’est Comme Un Jour”). Set to string accompaniment that is alternately shivering and uplifting, Giddens’s “Tomorrow Is My Turn” combines the elocution of an opera singer with the self-possession of a classic blueswoman and the subtle swing of a sophisticated nightclub entertainer. In her approach to the phrase “Tomorrow is my turn / to receive without giving,” you can hear a yearning tempered by the wistful wisdom that comes with an awareness of the world’s cruelty, as well as its beauty.

The prophetic optimism of the title track takes a backseat to full-throated vexation in “Cry No More,” Giddens’s haunting, black feminist musical response to the June 2015 massacre of nine black churchgoers by a white gunman at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Released as a video, “Cry No More” features Giddens, surrounded by members of United Congregational Church in her hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina, in a vigorous call-and-response. Cowritten with Giddens’s sister Lalenja Harrington, “Cry No More” begins with the image of Giddens walking away from the camera up a dimly lit church aisle while beating on a frame drum with a mournful, hollowed-out sound. We see people, roused by the drumbeat, following her from the pews to the pulpit. The song begins as a low moan, takes the listener through a historical overview of American racism, and ends with an urgent drumbeat to action:

Although the tragedy it refers to is centuries removed from the tragedy that animates “Julie,” “Cry No More” has the same unsparing appeal, investing hope in the resilience of ordinary people to carry on in spite of it all. The “home” the song imagines is also the home that Julie seeks, a place far away from hells masquerading as safe spaces.

Of late, Giddens has been performing and composing on a custom reconstruction of an 1850s banjo popularized in traveling minstrel shows. It is—as she explained to me, a fan who is also a total banjo neophyte—fretless, with a skin head that gives it a hollow timbre and strings made of a synthetic material that approximates the sound of animal gut. It was a banjo Giddens had long been searching for, drawn to the ephemeral beauty of America’s first popular music and to the complex relations of racial “love and theft” (in a phrase memorably coined by scholar Eric Lott) that supported its development. She also just loved the way it sounded. When Giddens, who had been searching for a minstrel banjo, tried an instrument handcrafted by Jim Hartel at a gathering of people interested in early banjos, she had her aha moment. “It was like one of those things when you pick up an instrument and you start playing it and you’re just like, ‘How much is this? I don’t care. Here’s my bank account. Just clear it out,’” she recalled in a 2015 episode of the PBS series Craft in America.

No person living today knows exactly what an 1850s minstrel banjo sounded like; the music that was made on such instruments predates the invention of recorded sound. But we know that the banjo was brought to America by Africans, and that white players, including Thomas F. Briggs—author of the first banjo instruction book, an invaluable resource for historians and musicians—learned from black banjoists. When Giddens composes for or performs on her banjo, she channels both the history and the mystery of early American banjo music: what has been passed down as well as what has been lost. “Julie” is a perfect example. It’s a song that conjures the sonic pleasures of the minstrel stage, which produced dozens of memorable songs that retain their allure to this day. At the same time, it gives voice to the rage and grief of an enslaved black woman—exactly the sort of black interiority the minstrel tradition erased, or hid behind the masks of comedy or parody.

While writing “Julie,” Giddens schooled herself in the experiences of slaves during the Civil War—she names as an important influence Andrew Ward’s 2008 book The Slaves’ War: The Civil War in the Words of Slaves—and spent time in archives examining primary documents of slavery, an experience winkingly referenced in the delightful video (filmed in the library at Nashville’s Fisk University) for her upbeat take on the coffeehouse staple “Black Is the Color.” A bill of sale she discovered during her research was the sorrowful inspiration for “At the Purchaser’s Option,” her wrenching song about the buying and selling of enslaved children without regard for kinship relations. To say Rhiannon Giddens has “done her homework”—a cliché in the world of traditional music, where such meticulous attention to source material is perhaps expected—is a whopper of an understatement. Giddens has earned her advanced degree and is more than qualified to teach the class.

Yet she wears her erudition, and the political commitments that shape her interrogations of history, lightly. Neither “Julie” nor “At the Purchaser’s Option”—both of which will be among the tracks on a forthcoming full-length recording due out from Nonesuch in early 2017—are studied, and each makes full use of music to tell their stories. At her performance at Lisner Auditorium, “At the Purchaser’s Option” had a modern, veering-on-hip-hop sound, although the source material is quite old. The synthesis of polished modernity and respect for tradition is a hallmark of Giddens’s approach on the new album.

“I try to pull that stuff forward,” she said over lunch in New York. “Past is present.”

A striking publicity image of Giddens by photographer Michael Weintrob captures what is transgressive and exciting about this biracial black native of North Carolina (re)claiming an instrument and a sound associated with the ignominious practice of “blacking up.” In the image, Giddens directs her gaze squarely at the camera, the Hartel slung casually over her left shoulder, a bit like how a farmworker might hold a shovel or a hoe. The look Giddens wears is neither an invitation nor a dare. It’s a look that asserts her fearlessness in mining minstrel music, the legacy of which is audible in children’s playground chants, hip-hop samples, and the tinny songs of ice cream trucks.

Giddens notes that, like “Julie,” the other songs on her forthcoming record will ask much of listeners. These songs will require audiences to encounter, or perhaps re-encounter, an American past that, as Morrison reminded us, many would rather not think about. The new material will oblige audiences to attend to a challenging variety of voices: from the pleading voice of Julie’s white mistress, who imagines her slave as her friend, to the voice of Nat Turner, leader of an 1830s slave rebellion and the inspiration for filmmaker Nate Parker’s feature Birth of a Nation. Giddens laughed when she told me that her new album, which she is also producing, is being recorded at a “shack” in Louisiana. While she lacks the sort of material resources that attach themselves to a music-industry stalwart like T Bone Burnett, Giddens is committed to her musical “rememory” of American history. Few other musicians have the artistic and political audacity to invite listeners back in time—to the 1850s!—as a means of making sense of our current crises.

The playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and the visual artist Kara Walker have mined similar material in their respective creative forms. But the music business has historically been reluctant to reward black women when they stray from expectation or venture outside a narrow commercial realm. Giddens is perfectly aware of these constraints and is up for the challenge. In her hands and her voice, America’s messy collective story, musical and otherwise, has a skilled and sensitive interlocutor. Or as Giddens put it, “I take all the information and it comes out in the song.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.