Illustrations by Daniel Pagán

Los Vampiri

By Kevin A. González

On New Year’s Day, 1955, not long after my father turned nine, my grandfather won the first Lotería Extraordinaria drawn in Puerto Rico. Before the lottery, Papa Hector had been an absent man, but at least his truancies were typical: He came home late from work, went boozing with his friends, kept some chillas on the side. And this, while far from placid, was weather your typical family could steer through, particularly on the island, particularly with a devout Catholic mother like Socorro at the helm, but that winning ticket brought a tidal wave of such abandon, of indulgence so egotistical and madcap, it’s the miracle of miracles I’m here to tell this tale: After my grandfather won the lottery, he bought his wife a dachshund and took himself to Spain.

He purchased a Rolls-Royce in Madrid and trekked all over Europe, from Porto to Salerno to Brussels to Marseille. Five months later, he sold the Rolls-Royce for a profit and returned to Puerto Rico with a silver medieval door knocker and a Cuban girl named Marta. He put her up in an apartment in King’s Court, less than a mile from his family’s house.

And back home, how Socorro loved that dachshund! How he strutted behind her through Condado with a little bell around his neck! Lotería was his name, and they knew him at the bank, the beauty parlor, the colmado. And where was my father, Hector Jr., in all this?

“If that wiener dog had caught on fire,” he told me decades later at the Round Bar, “I wouldn’t have even pissed on him.”

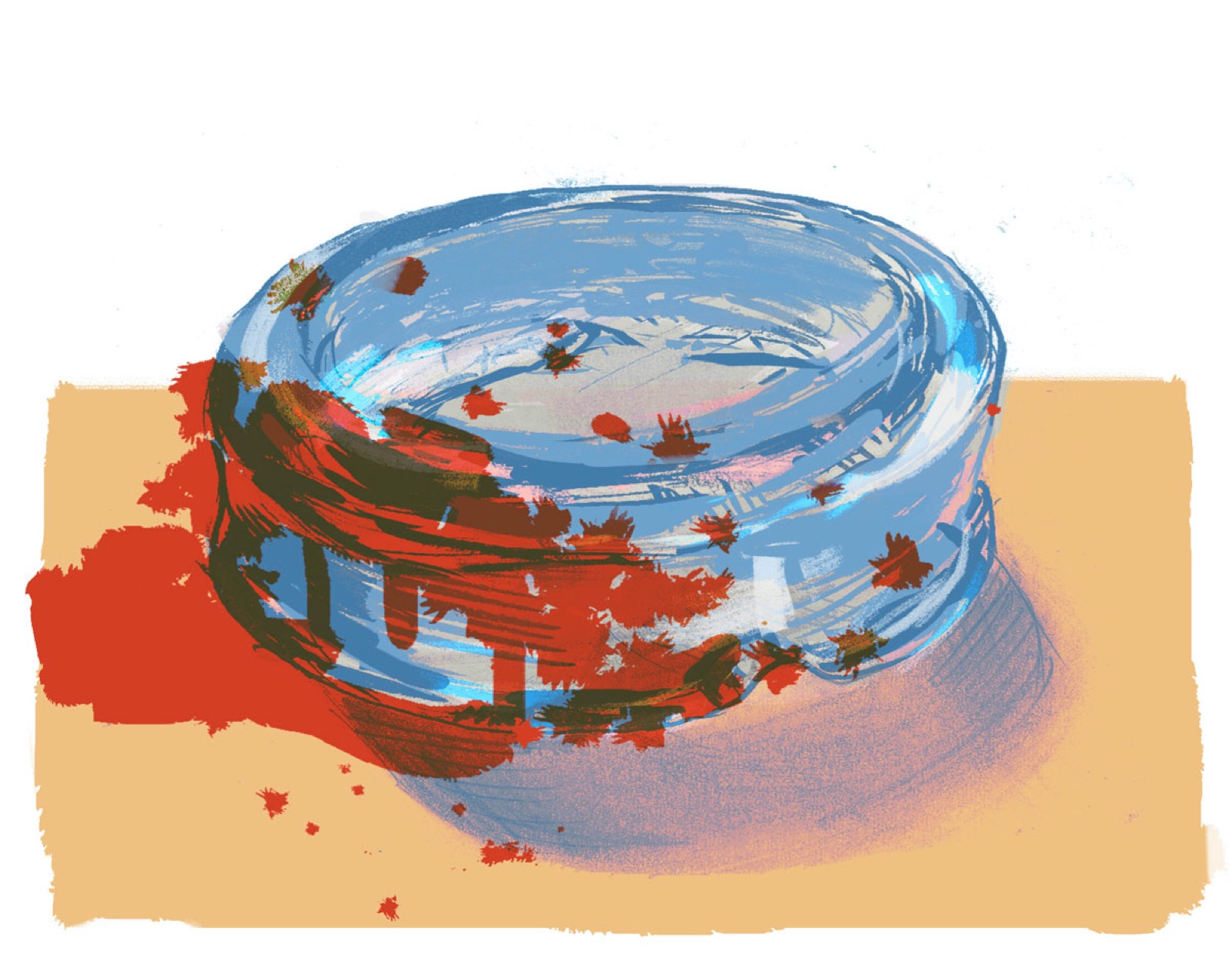

On the evening my grandfather returned from Europe, he bolted the medieval knocker to the door, took his family to the Bankers Club for dinner, then spent the night with Marta at King’s Court. At nine years old, my father noticed a few changes. Suddenly, they had a maid and a chauffeur. Two shiny rides appeared in the driveway: a black Lincoln Continental and a green Cadillac Eldorado. He remembered a TV, endless comic books, a BB gun. But mostly he remembered the nights his father spent with Marta. How he’d wake to use the bathroom and find his mother smoking at the table, clutching a tepid cup of tea. And in the mornings, how she’d yell at Papa Hector when he would come home to change clothes, and how this went on for months until one morning he walked in and she threw a glass ashtray at his forehead, opening a deep cut. Papa Hector took off in a rage and climbed into the Caddy with blood dripping down his face. There was so much blood, and he was so incensed, that it wasn’t clear whether or not he’d seen Lotería, whether the dog’s death had been an accident or a spiteful act of vengeance. Papa Hector later swore he never saw the dog, never glanced up at the rearview as Socorro ran outside and threw herself beside its body. She rose, gripping a rock, and went to town on the windshield of his other car, screaming incoherently, making a stabbing motion with her arm, until finally the chauffeur came to restrain her, and the maid rushed to call an ambulance. Both she and Papa Hector wound up at Ashford Medical, he with twelve stitches in his forehead and she full of barbiturates. My father remembered how they’d come home together, how his father tucked his sedated mother into bed before taking off again, and how, as he left, he didn’t say a word, how there was a bandage on his head and dried blood on his shirt. Here is the lesion and here is the scar, here the unguent, and here the salt.

My telenovela family, I call them.

And yet, when I can’t sleep, I ask myself: If not for the money from that lottery, where would I be today? Would I still have studied history in college, and would I have fled to California, and, if not, how would Becca and I have met? Would we own this house in Lincoln Park, and would we donate money to NPR, and would I be enrolled in law school at Northwestern, and would Becca have the time and space to make her art? And if things hadn’t worked out this way, if we lived in a one-bedroom in West Ridge up to our necks in student debt, would we have tried and tried and tried to have a baby until finally, six months ago, two lines showed up on a test? If not for the Lotería Extraordinaria, would we be going out of our way to bring a son into this world?

That ashtray must have fixed something loose in Papa Hector. He continued seeing Marta, but he came home every night to sleep beside Socorro. She, in turn, soon came to overlook his indiscretions, much as she’d done in the past, as long as Papa Hector wasn’t blatant. In the soothing silence that ensued, he began to write his memoirs, and a political agenda slowly etched itself into his head. He’d always been a Statehooder, a Republican Statehooder, and now he had this extra cash and extra time. He started by throwing a fundraiser at the Bankers Club, and before long, he’d piggy-banked his way into the party. By 1960, he was the Statehood Party chair, and in 1962, he launched a campaign for the Senate in San Juan.

It was around this time that my father and his friends started a gang. They were all blanquitos from Condado: Yasser Benítez, Claudio LaRocca, Tommy Del Valle, and Juanma Thon. On the night their gang became official, they downed a bottle of Bacardi, then smashed it into pieces and used a shard to cut their arms. Then they rubbed their wounds together, so the blood passed from arm to arm. Hector was the youngest of the five, and he’d gone first, snatching the glass and carving a deep, hook-shaped incision on the backside of his arm. Yasser just picked a scab around his elbow. The other three scratched pathetic little nips into their arms, rubbing the glass back and forth as if they were scraping paint off an old car. Hector was the only one bold enough to give himself a scar, and though a part of him felt cheated, an even larger part felt like he’d proven something to the guys, like his gung-ho commitment to the act made him the leader of the gang. They called themselves Los Vampiri, inspired by the Bacardi logo of a bat, and after a policeman brought my father home one summer night because they’d gotten into a brawl at the Red Rooster with a rival gang from Miramar, Papa Hector took him straight to the garage. He removed his belt and instructed Hector to shut his eyes. The boy took his whipping like a champ, and the following morning Papa Hector picked up the phone and made a generous donation to a boarding school in Massachusetts. How’s this for win-win: You exile your most risky liability to some prestigious academy that you can brag about in your campaign. And with the boy out of the way, you have so much time to run for office, to have dignitaries over without worrying about what the little prick might do or say.

It took my father sixteen years and a trip across the ocean to learn he was not white. Although Goebbels himself wouldn’t have batted an eyelash at Hectorcito, with his green eyes and Roman nose, he might as well have gone to Andover donning a pencil mustache like Cantinflas, wearing a sombrero. At the school, besides Whiteboys, you had Sand Niggers, Kikes, and Spics, and that’s how they all referred to one another, jokingly, as if their playfulness could offset their offense. Ha! Hector thought. Hardy-fucking-har! The weather didn’t help, but more than that, the problem was the people, who were colder than the air. All the boys were constantly competing, though he couldn’t tell what for. One minute, you thought you had a friend, but then he turned on you because you mispronounced a word, or outdid him on a math test, or because you failed to score from second when he hit a liner into center. At night, Hector stayed under his blanket with a comic book, his mind drifting to his blood brothers in San Juan, whom he pictured sipping Cuba Libres at La Concha, trying to talk the pants off some gringa tourist skanks. The thought made him want to run into the woods and decapitate a pine.

But Los Vampiri weren’t the only ones he missed. Even at sixteen, Hector wasn’t afraid to say he missed his mother, inasmuch as he knew she missed him. All the poor woman had ever done was tend hand and foot to Papa Hector. Every afternoon, the old man would pace around the living room dictating his memoirs to Socorro, who’d sit at the typewriter, punching in the mundane details of his life. She wrote to Hector every week, but the letters all revolved around his father: updates on his political campaign and which dignitaries he had dined with, how the new chapter of his memoirs was about the island’s path to statehood. There was never a word about herself, and within this sweeping vacancy, Hector felt aware of his own absence from her life.

And then there was Larisa, his girlfriend of two years: a hazel-eyed blanquita whose body could have melted all the snow in Massachusetts. When he first arrived at Andover, he’d placed a photograph of her above his desk. One day, unbeknownst to him, the boy across the hall—a Jewish kid named Ari who was an editor for the Phillipian—made a copy of the photo and published it under a segment called “Hometown Sweetheart Watch.” After Hector saw the paper, he walked right up to Ari in the middle of the Commons and punched him in the mouth.

The headmaster put Hector on probation. Then, during Finals Week, he was expelled. Earlier that fall, he’d met two Mexican laborers in the town, who, for a nominal fee, would buy him cigarettes and booze, which Hector then resold for a profit at the school. The end of the term brought a high demand, but it also brought a snowstorm, so the weekend’s shipment was delayed. Lance Ransom, a lacrosse player from Rhode Island, got on Hector’s case.

“It’s just a little snow, man. And here I thought Spics were so tough.”

Hector shook his head. “It’s snowing too hard.”

Ransom mimicked Hector’s accent and pretended to cry. “Oh, is es-nowing too har! Is es-nowing too har!”

Hector stared at him. “Vete pal carajo, maricón.”

“Chinga tu madre,” Ransom said, laughing. “Tu madre puta maricón.”

Hector lunged and wrapped his hands around Ransom’s throat. “What’d you say?” he yelled. “Say it again! Come on! Say it again!” He squeezed, and it took three boys to pull him off.

The next day, Hector met the Mexicans in town, and after he returned to campus with a knapsack full of cigarettes and booze, the headmaster, acting on a tip, conducted a surprise inspection of his room. Because of his father’s donation, Hector was allowed to finish his finals and salvage the term, but the headmaster informed him that he would not be welcome back. “Needless to say,” he said, “I will be writing your father, so I suggest you speak with him first.”

On the flight home, Hector replayed these words in his head. Writing, the headmaster had said. Not phoning, not wiring, not a vague touching base. Still, he arrived on high alert. As he got off the plane, he saw his parents at the edge of the runway. The heat, which he’d longed for and glorified, now seemed excessive, and his Andover blazer felt like a straitjacket.

Socorro ran up and placed her hand on his cheek. “Hectorcito, que guapo! Mira, que guapo!”

Papa Hector was standing behind her, holding a black umbrella over her head. She carried it everywhere—she had sensitive skin, and her doctor had instilled in her an absurd fear of sunlight. When she was done fawning, Papa Hector stepped forth and shook Hector’s hand. “You need a haircut,” he told him.

The Lincoln was parked in front of the terminal. The chauffeur took Hector’s bags, and Hector climbed into the back with his parents. As they were leaving the airport, Papa Hector leaned forward. “He needs a haircut,” he told the chauffeur. “Take us down to the Pierre.”

“I think he looks good!” said Socorro. “Hectorcito, you look like an actor.”

“Please,” said his father. “A regular greaser from West Side Story. No jodas.”

This was precisely the look Hector was going for. He’d grown his hair long and slicked it all back, parting it behind his ears so that both sides converged in a duck’s ass. It had taken months to perfect, but now, what could he say?

“Pray the barber’s still in,” Papa Hector said. “You’re not coming to dinner looking like this.”

Dinner! If Papa Hector had heard from the headmaster, they wouldn’t be going to dinner.

Then again, it wouldn’t have been unlike Papa Hector to take him to the best restaurant in San Juan, order a bottle of Dom Pérignon, and then, right as Hector was cutting into his steak, raise his glass and say, “I hope you enjoy this, my son, because it’s the last fucking meal you’ll eat in your life.”

Me? If I had been my father, I would’ve come clean on the tarmac. But as they pulled up to the Pierre, everything seemed dandy: The barbershop was open, and while Hector got his hair cut, his parents waited with a cocktail at the bar. Afterward, they drove to the Bankers Club for dinner. The restaurant was in the penthouse of the tallest building in Old San Juan, and when the elevator began to rise, Hector made a beeline for the glass. And there, finally, his ocean. Beyond the pastel houses of La Perla and the red dome of the cemetery, the waves exploded on El Morro. Hector shut his eyes. It was the twenty-second of December. If the headmaster had sent the letter on the afternoon he’d been expelled, he had at least three days to work with. Would there be mail on Christmas Eve? He couldn’t remember, for the life of him, if he’d ever received a letter on Christmas Eve. Hector opened his eyes, and when he turned, he saw his father standing by the bar, talking to his lawyer, Capi Baldrich. He quickly looked away and joined his mother at a table.

“Mami,” he said. “Do you know if there’s mail on Christmas Eve?”

“Are you expecting a letter?”

“No. It’s okay.”

“Hectorcito, you write such lovely letters. Do you have a new pen pal?”

“No, never mind. Forget I even asked.”

Despite his mother’s attempts to make their dinner pleasant, Hector couldn’t help but fixate on his father. It certainly didn’t help that he was all Socorro spoke of. “Your poor father!” she said. “So preoccupied with work! You couldn’t possibly imagine the grind, the absolute grind, of a political campaign!” His memoirs, she assured Hector, were sheer genius. Throughout this, Hector nodded automatically. He pictured her at the restaurant in his absence, eating by herself while his father drank with Capi at the bar. And he pictured her at home, sitting at the typewriter while his father paced around, smoking and dictating his memoirs to her. Hector had seen their routine for years: Every so often, Papa Hector would stop speaking and ask her to read back. Then, not long after she’d start, he’d rip the sheet out of her hand. God forbid there was a typo or some turn of phrase he didn’t like. You could fill the Grand Canyon with all the sheets he balled up and discarded. And later on, after he’d gone off to meet Capi at the Bankers Club for a Chivas, or after he’d sneaked off to Marta’s for a second dinner, guess whose job it was to pick up all the trash?

I was sixteen when my grandmother died. After the funeral, my father and I were drinking at the Round Bar. “He couldn’t have gone first?” my father said. “He couldn’t have given her a couple years of peace?”

I nodded and sipped my Cuba Libre.

“Carajo,” he said. “She should’ve thrown an ashtray at his head every morning of her life.”

After dinner at the Bankers Club, he and his parents climbed into the Lincoln. When they arrived at home, the chauffeur took Hector’s bags into the house. Hector followed, but before he reached the door, Papa Hector called his name.

“Come with me,” he said, and he turned toward the garage.

“Oh,” Socorro said. “Can I come, too?”

“No,” said Papa Hector, without turning back to look.

Hector glanced at her as he caught up to his father. She smiled as if to say, I don’t agree with him. Please do not blame me for this.

Papa Hector slipped the key into the lock and put a hand on Hector’s shoulder. He told Hector to close his eyes, and then he opened the garage. Hector did so and breathed deep, taking in the smells. It seemed as though just yesterday he’d stood there, braving the leather belt, with the damp wood like a swamp and the motor oil like a maze and Papa Hector’s breath like a dry well. Here is the lesion and here is the scar.

Hector braced himself.

Then the lights came on, and the insides of his eyelids went bright red. “Papi!” he said, opening his eyes. “Papi, wait!”

And there stood Papa Hector, beside a Buick Skylark Special.

Hector looked at it, perplexed. It was a red convertible coupe with a Fireball V6 under the hood and leather bucket seats.

“Well,” Papa Hector said. “What do you think?”

“It’s beautiful.”

“It’s yours.”

“What do you mean?”

“Merry Christmas.”

“What do you mean?”

Papa Hector laughed and tossed him the keys. “Go ahead,” he said. “Take it for a spin."

Check him out, cuising through Condado with one hand on the wheel, his elbow on the doorframe like a wing. The Skylark’s top is down, but his hair is anchored like cement, all slicked back with Brylcreem. He barrels down Ashford and turns left on Calle Tapia, trailing Chubby Checker in his wake. He honks and aims the headlights at Yasser’s parents’ mansion and sees his boys shooting dice out on the porch. Someone takes a roll, but when Los Vampiri all see Hectorcito, they rise up from the table and push up against the Skylark before the dice have settled on a score.

“Watch the paint, cabrones,” Hector said.

Juanma yelled out, “Piña!” and they all rushed to Hector’s side and started to whack him on the head. Hector covered up, but Yasser moved his hands out of the way.

“Mercy!” Hector yelled, and they backed up, laughing.

He stepped out of the car and punched Juanma on the shoulder, and then the five boys took their places. They settled in a circle and performed a sequence of slapping hands and snapping fingers, a convoluted secret handshake that ended with each boy smoothing his palm over his hair, then flicking his wrist as though getting rid of excess gel.

Yasser nodded at the Skylark. “Christmas gift?” he said.

“Something like that,” Hector said.

Yasser pointed at a white Chevy across the street. “That’s me over there. Five bucks I beat you racing.”

“Make it ten,” Hector said. “And I’ll steer with my dick just to make it fair.”

They all laughed, and Claudio put his hand on Hector’s shoulder. “Cabrón,” he said. “Have you seen the tiger yet?”

“What tiger?” Hector said.

“Oh, shit. You haven’t seen the tiger?”

“Pendejo, he just got here,” Yasser said. “If he’s asking what tiger, do you think he’s seen the tiger?”

“What the fuck about a tiger? What tiger?” Hector said.

“Shere Khan,” said Claudio. “But we call him Shere Cabrón.”

“Come on,” said Yasser, and led the boys into the house. The place had the frigid feel of a museum—all bronze sculptures and white cushions, Tiffany and Baccarat on every shelf. If you opened any window, the surf from Ocean Park would nearly spray your face. The five boys crossed the living room, and Yasser slid open the door to the backyard.

Almost forty years later, after Yasser’s parents had passed away and Yasser had turned this mansion into a fifteen-unit beach hotel, my father moved in. This was after my mother finally got fed up with the drinking, the gambling, the affairs, and he had nowhere else to stay. And every day he’d slide open the same door, and there’d be the same Atlantic, and on weekends and summers I’d be there, and Norman, the bartender, poured our drinks at the Round Bar in the yard, where we drank the days away. As the sun fell, the joggers overtook the beach and a guy we called El Metal Man went by, sweeping his metal detector through the sand. On the edge of the yard, there was a hot tub that never worked, a hammock tied between two palms with coconuts dangling by a thread.

But in 1962, the yard was an empty lot, and only a massive chain-link fence divided the beach from the estate. And as Hector stepped outside, he saw, on his own side of the fence, a Bengal tiger, pacing.

He threw his arms up in the air. “Fuck you,” he said, and spun back into the house. He shut the sliding door behind him.

Outside, the boys all started laughing.

“Fuck you,” Hector said again, pressing his face against the glass. “Is that thing real?”

“No, pendejo. It’s stuffed,” said Yasser.

“He’s harmless, man,” said Juanma, opening the door. “Doesn’t even have his claws.”

Hector shut the door. “I don’t care if all its teeth have fallen out. I’m not going near it.”

“Pssst,” said Yasser and walked up to the tiger. He rubbed its ear and ran his hand along its back. The tiger raised its tail, and Yasser tugged it a few times, making a jerk-off motion with his hand. The tiger didn’t flinch. “See? He’s a pussycat, I’m telling you.”

Hector stepped outside. “What the fuck’s it doing in your yard?”

Yasser shrugged. “Security, man. There’s been a few break-ins down the street.”

“And you people never heard of Dobermans?”

Yasser smirked and walked over to the shower. It was the outdoor kind you’d find at a hotel, on a patch of fancy tiling. “Can a Doberman do this?” Yasser pulled a chain, and a cascade of water fell. And with that, the tiger turned around and showed everyone his fangs. Out came a roar so loud you could’ve heard it in Nepal.

Hector shoved Juanma out of the way, and Juanma pulled on Tommy’s arm, and Tommy tripped up Claudio, and they all ran back inside. Yasser started laughing. “Pussies,” he said, shutting off the water. And just like that, the tiger’s snarl turned into a yawn and he returned to pacing back and forth.

After a round of Cuba Libres and another game of dice, Claudio suggested the Black Angus. Yasser and Hector both wanted to drive, so the boys split themselves between two cars. Juanma rode with Hector. At the time, if you’d been able to make my father talk, he would’ve told you that out of Los Vampiri, he felt the tightest bond with Juanma. Their families were close; the boys had known each other since before either one could walk. In 1955, after Papa Hector won the lottery, he’d talked Juanma’s father into joining him in Europe, and during the time they were both gone, Hector and Juanma had shuffled back and forth between houses, their mothers taking turns letting the other breathe.

In the afternoons, they’d sit around with comic books—Superman and Captain Comet, Vault of Horror and Weird Science.

“If only Papa Hector hadn’t thrown out those comics,” my father would tell me at the Round Bar. “They’d be worth a fortune, and maybe I wouldn’t be living in this shithole.”

I nodded, though what he would’ve done is pawned them and lost the money playing blackjack at the Sands.

At night, Juanma and Hector would make up heroic tales about their fathers—They were crossing the Sahara! They were hunting lions on safari!—and despite the evidence in front of them, at nine years old, they cast their mothers as villains. So often, this is how it works.

Every weekend, I could have chosen to stay home with my mother. But when I was thirteen and she got remarried to a man with the charisma of wet cardboard, I chose to join my father at the Round Bar, listening to stories from his youth and watching him drink Scotch until Norman’s arm was sore from pouring. I sat on the next stool, and in three years, I graduated from Cherry Coke to Heineken to rum. On more than one occasion, I woke up disoriented and alone in my father’s hotel room because he’d sneaked off to a poker game or to some random woman’s bed. When I confronted him about this, he said, “No one’s telling you to be here, babe. If you don’t like it, you can go back to your mom’s.”

And what did I do? I shut the fuck up.

Back inside the Skylark, Hector turned to Juanma. “Tell me this. Any new talent at the Angus?”

“There’s a couple of gringas and a bunch of colombianas.”

“Eso.” Hector raised his fist. “I haven’t had any since last summer.”

“You been to see Larisa?”

Hector shook his head. “I’ll go over in the morning.”

They were coasting along Ashford, looping the lagoon, taking the long way to Miramar. Yasser was zigzagging behind them, looking for breathing room to pass.“Listen,” Juanma said. “Don’t go crazy on the messenger, but I have to tell you something. Harold Venus has been talking.”

Hector turned. “About what? What are you saying he’s been talking?”

“About Larisa. He says they kissed. He says . . . Look, don’t get pissed at me, but he says he sucked her tits.”

Hector looked down at the road. He tried to play it cool, but a sharp heat seeped into his head and began to roll over on itself, spreading like a swell. Suddenly, he felt fucking more awake than he’d fucking ever felt.

“Did you see them?”

“Together?” Juanma said. “Fuck no. You think I would’ve stood there? No, man. I’m just repeating what I heard.”

They came to a red light, and Yasser pulled his Chevy up beside them. He revved the engine and yelled at Hector out the window. “About that bet,” Yasser said. “How’s this: Loser gets the winner laid.”

Hector flipped him off, and before the light could even think of turning green, he stomped down on the pedal. The tires squealed; Juanma’s head snapped back like a wrist.

“Coño!” Juanma said. “You trying to get us killed?”

In the rearview, Hector saw Yasser run the light and cut off a little Datsun. “Who else knows about all this?”

“Will you watch the fucking road?”

“Where can I find that maricón?”

“Man, I’m sure he made it up.”

“Of course he made it up! You think she’d look twice at that frog? At that ugly maricón?”

Hector jerked the wheel and swerved around a car. They were on the Dos Hermanos Bridge, and behind them, Yasser’s Chevy was gaining speed.

Venus had been Hector’s classmate through eighth grade. The kid had massive ears and couldn’t swing a bat, and here the fucker was, suckling on Larisa’s— No! What he was doing was spreading outrageous, blatant lies!

“Where does he hang?”

Juanma put both palms on the dash. “He runs with some pendejos from King’s Court. Los Kamikaze, that’s what they’re called. But they’re nothing, man. They’re just trying to be like us.”

Two blocks ahead, Hector could see the red neon of the Angus. He cut off an old Packard, and the Packard ate a piece of sidewalk. Yasser fell too far behind. “Tomorrow night,” said Hector. “He’s fucking dead tomorrow night.”

They spun into the parking lot, and the gravel flew into the air and rained down like confetti.

Dumbo. Basset hound. Rata. Orejón. He looked like a Volkswagen Beetle with both its doors flung open. If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around, Harold Venus hears the sound. And here’s the thing about Larisa: Back then, Hector hadn’t even seen her breasts.

“Let me get this straight,” I said at the Round Bar. “You were sixteen and you’d been dating this girl for two years and you hadn’t seen her tits?”

“It was a different time,” he said.

“What? A time when you were gay?”

The looks he gave me. I wouldn’t have wished them on Torquemada!

But no, it was a different time like this: When Yasser pulled into the Angus, the five boys went inside, ordered Cuba Libres at the bar, and each picked out a girl. This is how it worked: You paid a quarter for a dance, and then, during the dance, you’d negotiate a rate. Then you’d take your girl upstairs, where you’d come face to face with San Pedro, a large, frightening moreno in a beret, named after the keeper of heaven’s gate. You’d pay him two dollars for a towel and a room, where you got twenty minutes to do what it was you’d come to do.

If you were a blanquito from Condado, your allowance covered everything, and still, you’d have enough left over to take your girlfriend to the movies. And oh, to hold her hand and kiss her lips and cop a feel over her blouse! And to blush there in the dark when she slid your hand from her thigh and placed it gently on her knees—her pale ceramic knees, which rhymed like couplets with her cheeks! And perhaps this was part of the appeal: how these high-society blanquitas were all born with the same gene, a comemierda chromosome that rendered them incapable to lie naked with a boy until they looked down at their hands and were blinded by a ring.

And so the boys took their hungry mouths into the Angus, and along with the swabbies and the suits, they feasted on putitas. What was the worst that could go wrong? The previous summer, Hector had picked up a case of crabs and, not knowing what else to tell his mother, he claimed he’d gotten it from the toilet in their laundry room. Then he did what any Condado boy would do: He blamed the maid, a paunchy dominicana named Yesenia, whose feet were always swollen and whose breath smelled like mangú. Socorro sent her to the drugstore for shampoo, and by the time the maid returned, her suitcase was waiting on the curb.

Another time, Hector had bumped into Larisa’s father at the Angus. They were there for the same thing, so what could his future father-in-law do? He bought Hector a few drinks, gave him a rambling lecture about marriage (the gist of which was this: “Every man has needs . . . Never raise your fists . . . When you cheat, check your feelings at the door . . . Secrets are important . . . You’re a good kid, I’ve always known you’re a good kid”), and then paid for his trick.

Tonight, on Yasser’s dime, Hector takes it to a colombiana from behind. Always from behind, and he shuts his eyes and thinks about Larisa. Guilt? This is what men did! Plus, he thought, talk to me the day Larisa gives me something. He’d put in two years on that project. And for what? For Venus to sweep in, with his massive ears like wings? For his friends to all believe he’s been made into a wimp? He squeezed the puta’s hips. Her head was down, her fingers linked, her torso inclined like a ramp. Halfway down her back, her frizzy hair was bunched like seaweed.

If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around, Harold Venus hears the sound.

Hector opened his eyes, grabbed her hair, and yanked it back as though her head was a motor he was trying to start. With his other hand, he slapped her ass.

“Oye! Coño!” she yelled.

Hector let her go, and she sprang forward on the cot. “What’s wrong with you?” she yelled, and slapped him on the chest. “What’s wrong with you, you’d do that to a girl?”

“I’m sorry,” Hector said, and looked away.

She stood. “Big mistake. I’m getting San Pedro.” She went for the door, but he stepped in her way.

“Please,” he said. “Look, it’s my birthday. I’m sorry. It’s my first time with a girl.”

She looked into his eyes, and he crossed his hands over his crotch; he felt a sudden urge to shield himself. He was surprised by his own lie—he’d lied before, of course, so many times, and about matters more substantial, but now, for the first time, he was seized by his ability to have faith in a lie, to make this girl fall blindly for his fiction, to make her stop cold in her tracks and offer him a second chance. What was there to lose? It was like gambling with someone else’s cash, like being the player and the house all at the same time. “Come on,” he said. “I’m sorry. Let me have another try.”

She reached out and stroked his hair. “How’s this, bebé,” she said. “I’ll let you have another try, you let me have another ten.”

“No jodas.”

“Then how’s this. I go get San Pedro and you can talk to him.” She nodded at the door, and Hector pulled his wallet out and handed her a bill.

“First time my ass,” she said, and she got back on the cot. “You have five minutes.”

Seven minutes later, our boy was driving home, grinning like a mongoose. Comemierda.

Every man has needs.

I couldn’t say how many times I heard my father make this very proclamation at the Round Bar. When I was thirteen, after he and my mother were divorced, he told me, “Sometimes women would rather just be blind to whatever’s going on. They have no understanding of our needs. I know you don’t get it yet, but believe me, soon you will.” Several years later, I believed I did. And when I think of the man I used to be when I still drank, my chest is overrun with a catastrophic, septic shame that ebbs into my throat and saturates my tongue.

Now, sleeping next to Becca, there are nights in which my dreams betray me and I wake up drenched in sweat, my heart pounding, believing I’m still my father’s son. It’s been nearly ten years since we’ve spoken, and still I find myself searching for atonement.

In the evenings, when Becca goes to bed, I stay up, pretending to study, because I don’t want to shut my eyes and be taken from this world. Last month, on the day the ultrasound revealed the baby’s sex, she stopped into my office before she went upstairs.

“Hector Manuel,” I said. “What’s wrong with that name?”

“Nothing.” She smiled. “We’ll stock up on hair gel, and he can grow up to be a corny Mexican soap star.”

“Hector the Fourth.”

“Sounds like a Shakespearean tragedy.”

“I’m serious,” I said. “It’s a good name.”

“Of course it is. You know where I stand. If you want to name him that, fine. We can talk. I’m not completely opposed. But last week, you said, and I quote: ‘I’ll cut off my balls before I name my son Hector.’”

“That’s not what I said.”

She rolled her eyes. “I’m going to bed. Please empty the dishwasher before you come upstairs.”

Early the next day, Hector pulled up to Larisa’s. Before he even knocked, she ran out to the yard and threw herself around him. He kept his arms limp at his sides. “Do you have anything to tell me?” he said.

“God, I missed you!” she said, and went to kiss his lips.

He turned his head.

“What, mi amor?” she said. “What’s wrong?”

“First of all, don’t call me that. And you know damn well what is wrong.”

She narrowed her eyes. Softly, she said, “What?”

“Harold Venus is what.”

“What do you mean?”

He laughed. “If you’re gonna play pendeja, I’m done wasting my time.” He turned to leave, but she grabbed his arm.

“It was nothing. He took me to a dance. Our parents are good friends.”

“Look,” he said. “I don’t give a fuck if your parents are good friends with John and Jackie Kennedy. What coño do I care?”

He started toward his car, but she got in his way. “It was nothing! I swear!”

“If it was nothing, why didn’t you put it in a letter?”

She looked away. “Because,” she said, “I knew you’d be upset.”

“Oh, I see. All right. So if you knew I’d be upset, then why did you accept?”

“I don’t know! I’m sorry! I’m sorry, okay?” She started to cry, pressing her face into his chest. “Don’t go,” she said. “Please. I love you more than life itself.”

He grabbed her shoulders and moved her away. “What did you wear?”

“What do you mean?”

“To this dance! What the fuck did you wear?”

“I don’t know. A dress.”

“Which dress?”

She looked at the ground. “You haven’t seen it.”

“You bought a new dress for that pendejo?”

“No!” she yelled. “Not for him! I didn’t buy it for him!”

“Go get it. Show it to me. I want to see this fucking dress.”

Still sobbing, Larisa ran into the house. Thirty seconds later, she came out with the dress. It was a periwinkle blue that surely made her eyes the most magnificent sight in any room.

“I don’t ever want to see that ugly dress again,” Hector said. “Did he kiss you?”

“No!”

“Tell me the truth. Don’t lie to me, carajo! Did he suck your tits?”

“What? That’s disgusting!” she yelled. “How can you ask me that? Grosero!”

He instantly regretted it. He’d challenged her honor, and she had no choice but to swing. It was in her blood to be offended. He reached for her hand, but she shook herself free.

“No!” she said. “Vete! Leave me alone!” Then she walked into the house and slammed the door.

Hector drove to Ocean Park. He parked in Yasser’s driveway, walked down to the beach, and sat cross-legged on the sand. The air was cool, and the waves were spitting whitecaps from their crests; still, Hector considered diving in. He knew Larisa loved him; he’d never truly doubted this. He would send her orchids and she’d take a few days to forgive him, but what would the circumstances be by then? Papa Hector would soon hear from the headmaster, the Skylark would go back, and Hector would not see the light of day until enough strings had been pulled for him to be shipped off to another bullshit school.

It was all Venus’s fault. Dumbo. Basset hound. Rata. Orejón.

Hector stood. The beach was empty except for a few tourists wading in. He thought of his Andover classmates in the fall, boasting of their summers on the coast. Even now, this beach was whiter, its water warmer, than Cape Cod’s in mid-July. He heard an incision in the wind and turned toward Yasser’s house. A maid stood in the doorway of his backyard, holding a bucket with both hands. Without stepping outside, she flung its contents to the yard and slid the door shut in a flash. Twenty feet away, the tiger rose up from the grass. He approached the bucket’s contents and bent down, his tail curling like a rope. Breakfast, Hector thought, and then an idea stole into his mind, and he dashed around the house and knocked on the front door.

He laid things out for Yasser.

“I’m in,” said Yasser. “But we have to take your car. You’re not getting blood in mine.”

“Deal,” Hector said. “I’ll pick you up tonight.”

When Hector had woken up that morning, he’d found a note on his dresser. It was on his father’s stationery—Lunch, Bankers, 12:30—and when he walked into the restaurant, he was relieved, perhaps for the first time in his life, to find Papa Hector there with Marta.

“Guapísimo!” she said, and stood up for a hug.

Hector kissed and hugged her. At first, when he’d been nine or ten, he couldn’t help but feel like he was betraying his mother whenever he was in the presence of this woman, whenever she kissed his cheek or touched his hair, but with time, he’d come to regard her with the tepid fondness he would feel for a stepmother. Before meeting Papa Hector in Mallorca during his lottery trip of ’55, she’d been the mistress of Carlos Prío Socarrás, the president of Cuba who’d been ousted by Batista. Papa Hector, for some reason, was quite proud of this fact. He bragged about Marta’s past affair as though he’d won her in a sweepstakes.

“Hectorcito,” Marta said. “You must be driving the girls wild back in Boston.”

“It’s a boys’ school,” said Hector. “I didn’t see a single female for five months.”

She laughed. “Well, I hear you’re quite the athlete.”

Papa Hector slapped his back. “That’s right,” he said. “Here I am, spending a fortune on tuition so he can go play footsie with a bunch of Sandinistas.”

Hector wished he’d never written a single letter to his mother. Not a week after he mentioned he’d joined the soccer team, he received a postcard from his father. It had a Greek warrior on the front. “Dear son,” it said. “If you’re going to play a sport, at least play a real sport. Soccer is for communists. PS: Isn’t there a debate team you can join?”

“Oh, leave him alone,” said Marta. “I bet you score a lot of goals.”

“I’m the goalie,” Hector said.

“Great,” said Papa Hector. “Khrushchev would be proud.”

“You know, I play baseball, too. Is that American enough for you?”

“That’s not the point. Why go to the best school in the world to do something you could do in an empty lot in Barrio Obrero? You should be doing something better with your time.” He waved his hand. “Anyway, we’ll see what’s what when I get your report card.”

Hector poured himself some wine. “That’s right,” he said. “We’ll see what’s what.”

It was December 23rd. If Papa Hector hadn’t heard by now, surely he wouldn’t hear from the headmaster until after Christmas Day. How many lifetimes, Hector thought, in the great span between here and then? There were kisses to be won back from Larisa and miles to be tacked on to the Skylark. And in the meantime, would you look at that sun reflecting off the harbor, and at those tremendous lobsters shackled inside the fish tank by the bar—and Jesus fucking Christ, would you just look at all this wine?

“So tell me about school,” said Marta.

Hector took a sip and lied and lied and lied.

When I was eighteen, I was summoned to my grandfather’s bedside by his lawyer, Capi Baldrich. He’d been in the hospital for two weeks. When I arrived at his room, Papa Hector was propped up on the bed with an oxygen mask around his face. He couldn’t speak. There was a stack of legal papers on a tray table, and when Capi handed me a copy and began to read, I realized it was a will.

“Hold on,” I said. “Wait. I don’t think I’m comfortable with this.”

Papa Hector’s arm slowly crept under the railing. He took my hand, and Capi spoke as if he and Papa Hector were communicating telepathically: “Your grandfather is very proud of you. He loves you very much and wants you to have everything you need. He’d like for you to go to college, then on to law school.” I felt a squeeze.

“I need a minute.” I excused myself, but Capi followed me outside.

“Son, think about your future,” he said. “Don’t be rash.”

I pictured my father at the Round Bar, the labyrinth of broken capillaries on his nose, the bags under his eyes. “What about my dad?”

“Your dad will understand.”

I laughed. “He’ll never speak to me again.”

“Sure he will. Look, you have to understand. He’s not capable of doing this. With the way he gambles, the way he lives his life, if he were to see this money, how long would it last?”

I looked down the hall. The elevator opened; its down arrow lit up.

“If not you, your grandfather will find someone else to benefit. Believe me. His mind’s made up. Either way, he’s going to screw your dad.”

On the document, there was a Roman numeral at the tail end of my name, Hector Manuel Acosta III—that final downward stroke the only difference between my father and myself. I signed below this name on page after page, by turns frightened and grateful and excited and brimming with regret. I had no idea what my grandfather was worth, but I knew what I was doing, and I didn’t have the integrity to put down the pen.

Three days later, he was dead. When my father walked into Capi’s office, I couldn’t look him in the face. He gestured at me. “The fuck’s he doing here?” he said.

“Have a seat. Let’s get started,” Capi said.

My father sat and shook his head. “Shit. I’d known I was coming here to get fucked, I would’ve worn a pretty dress.” He slapped the desk. “Ram it in. Go ahead.”

When Capi finished reading the will, we sat in a long silence I couldn’t figure out how to break. My father owned that silence, even if he didn’t own anything else. Finally, he tapped his fingers on the desk. “Read it again,” he said.

“Hector,” Capi said.

“No. Read it again. Whatever my son was feeling while you read that, I want him to feel again.”

“Papi,” I said. “I don’t care about the money. I’m gonna help you out.”

He stood and tried to step around me, but I moved the same way.

“Wait. I’m sorry,” I said.

“Oh, you’re sorry. Well, then that solves everything. Now please, if you would be so kind, my son, could you get the fuck out of my way?”

At midnight, after orchids had been delivered to Larisa and many Cuba Libres had been drunk, Hector and Yasser left La Concha, drove the Skylark to King’s Court, and parked down the street from Venus’s home.

“Now what?” said Yasser.

“Now we wait,” said Hector.

Yasser pulled a small revolver from his pocket.

“What the fuck is that?” Hector said.

“A machete,” Yasser said, and aimed it at a trashcan on the sidewalk. He shut one eye. “Why do you ask such stupid questions?”

“You’re crazy,” Hector said. “Let’s go.”

“Relax.” Yasser put the gun down. “I took the bullets out. It’s just, you know, to ensure his cooperation.”

Even after six or seven drinks, Hector felt the adrenaline surge in, teasing his stomach like an ulcer. Throughout the evening, his anger at Venus had subsided; part of him wanted to start the car and drive away. But what would Yasser say? And what about everybody else who’d heard the lies Venus had spread? And what about Larisa, innocent Larisa, who’d been unknowingly blackened by his words? Venus couldn’t have just fibbed about a kiss. No, he’d had the gall to brag about her tits—her glorious, enigmatic tits, which drove Hector mad with speculation. The previous summer, as he prepared to leave for Andover, he’d asked Larisa to describe her areolas.

“I don’t know,” she said. “They’re round, I guess?”

“I know they’re round, bobita. But, like, how big?” He made a circle with his index and his thumb. “Like this?”

She blushed. “No.”

“Bigger?” he said. “Just tell me when to stop.” He slowly moved his fingers to make the circle bigger.

“Okay,” she finally said. “There.”

He looked closely at his hand. “Like that? Oh, man. Can I just see them once?”

“No!” She crossed her arms over her shirt.

“Okay, okay.” He walked over to her desk and grabbed a sheet of paper. “How about this. Draw them here for me.”

“Draw? I don’t know how to draw!”

“Come on. Just measure with your hand and trace the circles on the sheet. I’ll be outside.”

He walked out of the room before she could turn him down. Five minutes later, he came back. The sheet was on the desk, folded into a square. When he opened it, there were two circles on the page. “That’s them? Coño.” He brought it closer to his face. “Is the right one bigger than the left?”

“What? No! I don’t know!” She looked down at her chest. “Can we please talk about something else?”

Hector folded up the drawing and put it in his pocket. That night, at home, he locked his bedroom door, unfolded the sheet, and put it to his mouth. For the last six months, he’d kept it handy in his wallet. And there he’d been, freezing to death inside his dorm room, rubbing his lips against a stupid little drawing. Meanwhile, where had Venus been? At some dance, with his greasy hands around Larisa’s hips, drinking Bacardi, and then running his mouth like a motherfucking motor. Again, the heat charged in. Hector clenched his fists.

Just then, a Plymouth Fury turned onto the street.

“That’s them,” said Yasser.

Hector gripped the door handle.

“Not yet.”

The Plymouth stopped, and its passenger door flew open. Roy Orbison’s voice hurled out like an axe. Then Venus got out and shut the door, and Orbison ceased crying, and the Plymouth slid off like a shark.

“Now,” said Yasser, and they got out of the car.

Venus was heading up the driveway when Yasser called his name. He turned. “Who’s there?”

“It’s me, cabrón,” said Yasser.

“Me who?”

“Tu pai. Don’t be an asshole. Ven acá.”

Venus started toward them. When he recognized them, he stopped. “Yasser? Hectorcito?” He shrugged. “Qué pasó?”

They kept walking toward him. “All this time,” Hector said to Yasser, “and that’s how an old friend says hello.”

Venus shook his head and headed down the driveway. “My bad. I thought you were some títeres trying to steal my watch.”

“Relax,” said Hector, and when Venus held his hand out, Hector slugged him in the jaw. Venus staggered and Hector pounced, dropping him with a right cross above his eye. Hector winced and shook his palm.

Venus looked up. “What the fuck?” he yelled. “What’d I do to you, cabrón?”

Hector bent down and curled his hand around his ear. “Say it now. Say it to my face. What is it you did with my girlfriend?”

“What?” said Venus. “It was just a dance! We went as friends!”

Hector looked at Yasser. “What do you think?”

Yasser pulled the gun and aimed it down at Venus. “Get up, maricón.”

Venus put his hands over his face. “Is that thing real? Are you insane?”

“You might not believe this,” Yasser said, “but you’re not the first to ask me that today.”

They walked Venus to the car and popped the trunk. “In you go,” said Hector.

“Come on,” said Venus. “Is this a joke?” Yasser pointed the gun and, again, Venus covered up. “Stop that!” he yelled. As he was covering his face, Hector shoved his chest. Venus fell backward into the trunk, and Yasser grabbed his legs. He swept them in, and then they shut the trunk lid.

They parked by the beach in Ocean Park, and Yasser passed the gun to Hector. “Bring him around back,” he said. “I’ll open up the gate.”

After Yasser walked into the house, Hector got out of the car and listened for noises from the trunk, but there was nothing. When he finally popped it open, there was a peaceful look on Venus’s face. He stretched his arms and linked his hands behind his head. “This is a great trunk. Nice and roomy,” he said.

“Let’s go,” said Hector. “Get up.”

“I’ve been thinking,” Venus said. “And I think you should shoot me.”

“Is that right?” Hector held the gun up.

“You’re not gonna shoot me,” Venus said.

“Oh, I’m not?” Ten minutes in the trunk, and the kid had morphed into James Bond. Hector lowered the gun. “You’re right. I’m not. What I’ve got planned is even worse.”

“Well,” Venus said. “I’m not getting out. You’re gonna need a crane.” He looked at his watch. “It’s one a.m. Good luck finding a crane.”

Hector stood there for a moment, and when he saw a shadow on the sand, he stepped back from the car. Yasser walked up, holding a raw steak in his hand. “What’s the holdup?” he said.

Hector turned, but before he spoke, Venus leapt out of the trunk. He tried to run, but Hector tackled him and they both fell to the ground. Venus grabbed some sand and flung it into Hector’s eyes, and Hector screamed, and then Yasser was above them, kicking Venus on the side.

Hector stood and rubbed his eyes. When he opened them, he saw spots, as if someone had poked holes in the horizon. He returned the gun to Yasser and grabbed Venus by the neck. “Now you’re fucked,” he said. “We were just playing around before, but now you’re really fucked.”

They lifted Venus up, and Yasser bent his arm behind his back. They led him to the gate to the backyard. The night was cool and clear, the full moon brimming like a sail.

Yasser pushed Venus in and shut the gate behind him.

Venus turned to them. “What is this? House arrest?”

“Pssst,” said Yasser, and tossed the steak over the fence.

Venus leaned forward and caught it. “Thanks,” he said, “but I prefer it medium-rare.”

“Pssst,” Yasser said again, and began to jump and shake the gate.

“The fuck are you doing?” Venus said. “You look like an ape.”

Behind him, the tiger rose up from the grass, its eyes lit up like marker buoys. Hector’s stomach buzzed with adrenaline; he took a step back from the fence. This animal was straight out of William Blake’s poem. “Whatever you do,” Hector said to Venus, “don’t turn around and look.”

And, of course, that’s when Venus turned. He gasped and stiffened, and then every ounce of his bravado was cast out with one breath.

Yasser chuckled. “If I were you,” he said, “I’d get rid of that steak.”

Venus looked down at the steak and threw it like a Frisbee to the far end of the yard. Shere Khan gave chase, and Venus turned and tried to climb the fence. Yasser and Hector started laughing.

“This isn’t funny!” Venus said. It was a fifteen-foot-high fence with a rusty crown of barbed wire at the top. “Please!” he said. “Let me out! I’ll do anything you say!”

Hector and Yasser just laughed harder.

When Venus was halfway up the fence, Yasser swung open the gate and walked into the yard. He grabbed Venus by the leg and yanked him down. “Pssst,” he said again, and walked over to the shower. When the tiger approached, Yasser pulled the chain. The water fell, and out came the tiger’s roar. Venus shrieked. Inside the house, the lights came on.

Yasser shut off the water. “Coño. Let him out,” he said, and Hector opened the gate. When Venus came running toward him, Hector saw the wet stain on his pants. “Fó, cabrón!” he yelled. “He pissed himself!” Then he moved aside, and Venus took off down the beach like he was racing against his shadow.

Driving home, Hector felt a tired, heady satisfaction, as if in wreaking such destruction he had built something monumental and enduring. His eyes still burned, and his head felt heavy and rotund, as though the sand had seeped into his temples. Still, this was my father’s way: He took all impending repercussions and buried them in the most forsaken corners. Yes, the headmaster’s letter would arrive, there was pending business with his father, and, if they had any balls, Los Kamikaze would strike back—but now, why should he care? Venus got what he deserved.

Me? There’s no way I could have slept that night. If I had been my father, I would’ve broken down, confessing. I would’ve pleaded with Papa Hector, all to no avail. But my father has never had a problem taking to his bed while his enemies go seething, assembling their cases. He will sleep the most fathomless, black sleep while the snowball he set in motion continues rolling down the hill. He can say, “My son, get the fuck out of my way,” and then brush past you out the door and never speak to you again.

Goddamn them, our fathers: How disgraceful and desperate that we love them so much we can’t live our lives. How hopeless to try to impress them, and how fated we are to foam at the mouth when we fail, and how always, we fail. And what rage, what ridiculous rage, to think of them sitting around, sipping their Scotch, not thinking of us.

As he drove back home on Ashford Avenue, what could he have imagined? What was going through his mind? He might have suspected that his father would ship him off to a military academy in New Jersey, but he couldn’t have seen the war with the Kamikazes ending in the middle of the Dos Hermanos Bridge, with Yasser’s Chevy wrapped around a pole and Juanma’s body bleeding through a sheet. He might have understood that Marta and Papa Hector wouldn’t last forever, but he couldn’t have imagined her lying in her bathtub at King’s Court after emptying two pill bottles down her throat. He might have guessed he’d marry Larisa at the Bankers Club, but not that he’d leave her in two years because she couldn’t give him children. He might have known that someday he’d have a son, but not a son who would betray him, a son he would disown.

My telenovela family, at last.

Here’s what he was thinking as he parked the Skylark in the garage: There was half a New York strip left over from the surf and turf he’d ordered at the Bankers Club for lunch. He was starving when he climbed the steps up to the house, but as he turned in to the kitchen, something came down on his head. He hit the floor. When he looked up, there was Papa Hector, holding an antique wooden cane. He was about to swing again.

Hector put his hand over his head. “Papi!” he said. “Papi, wait! I can explain!”

And when the cane descends, I open my eyes, two thousand miles and fifty years away. My neck is soaked, and when I inhale, it’s the sweetest breath I’ve ever drawn. I don’t wake up Becca. Instead, I inch toward her and gently lay one hand on her stomach. I wait for a stir, for the life inside to announce itself like thunder. When you kick, I wouldn’t trade the sweat on the back of my neck for an eternity of sunlight. I’m fine, you and your mother are both fine, and no matter what you do, I will never turn my back. I swear it in my name, and in my father’s name and my father’s father’s name, in this cursed and wretched name that I swear will never be your name.