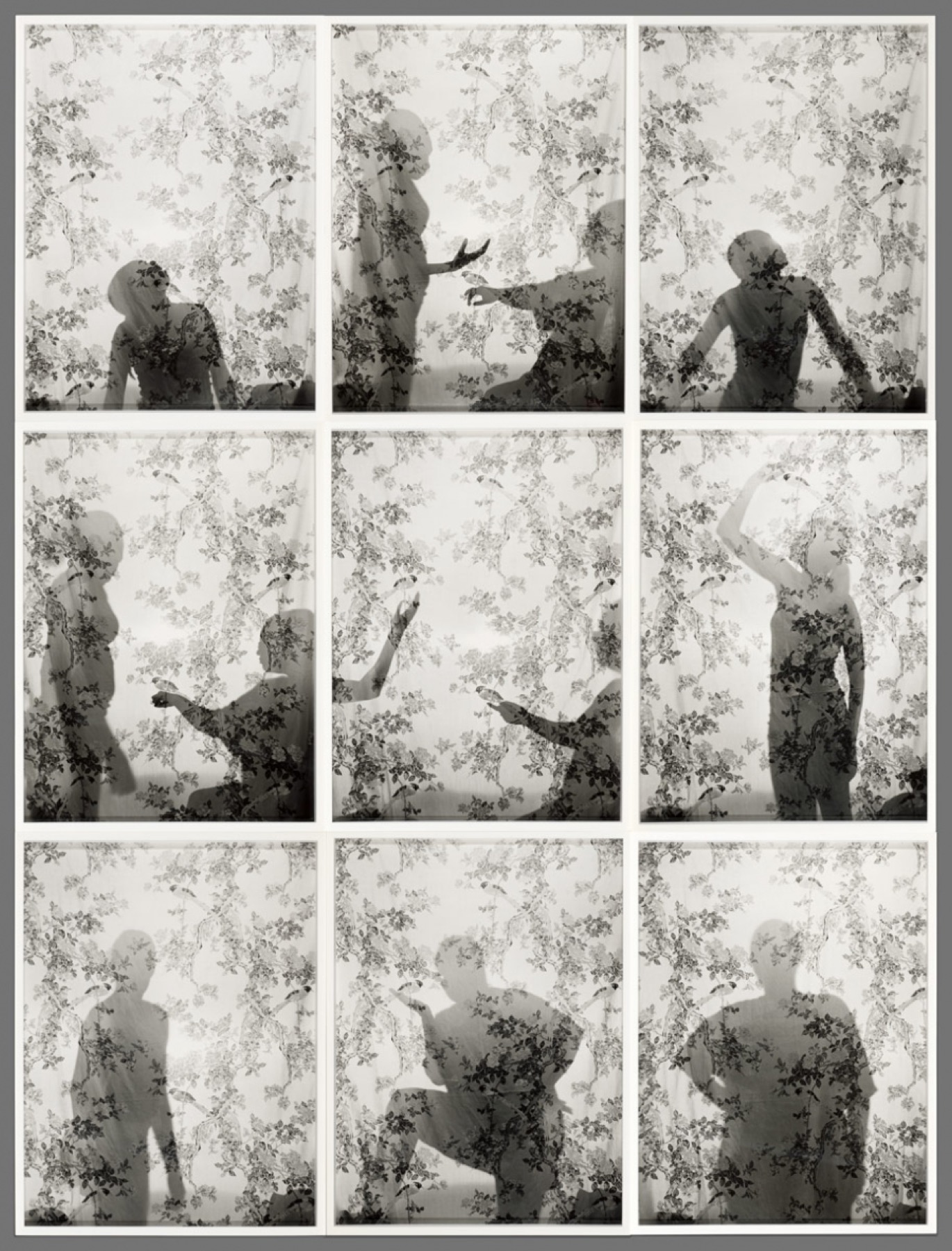

“Momme Silhouettes” (2010), from The Notion of Family (Aperture) by LaToya Ruby Frazier. Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Cleo, Cleo Black as Coal

By Crystal Wilkinson

I was country. A sad fly floating in the milk that was the city—the smell of exhaust fumes up my nose, tall buildings everywhere—and my heart, even my heart beat in my chest differently there. I hated the city. Some days I went to the park and while lying flat on my back, I situated myself among the trees so that there were no buildings in sight. When I closed my eyes and held my face straight toward the sun, I could see Mama and the other warm-faced black women I’d known my whole life plating catfish and broiled mutton alongside a bed of mashed potatoes and cabbage. I thought of the smell of food all the time and not just the taste of it. I thought of mornings so bitter they took your last breath as you gathered eggs from the chicken coop. I remembered Daddy taking me with him to the pig pen and calling “Soo-hee!” and the pigs—pink and gargantuan—running to eat the slop we’d made of corn and table scraps. I missed the smell of slop and even the smell of pig shit, but mostly I missed the warm smiles of the people I knew and the smell of untainted air.

Sometimes I dreamt of home and was miserable when I woke up and looked out my window and at other times I woke up grateful that I had returned home at least in my dreams. Sometimes in the night I ran through countryside so crisp and green that I could have sworn I’d been home in my daddy’s fields before my eyes popped open the next morning.

After a while, I came to expect that every building would look like the next, though this wasn’t always true. But it was rare to see patches of green between the concrete, the pavement, and the steel buildings unless you were in the parks. Droves of people moved together like cattle from one place to another without speaking, which made me crazy at first but then it made me a little happy that no one ever leapt out of the crowd shouting, “You’re Octavia Nelson’s girl, ain’t you?”

We stayed on the South Side in a rooming house.

The landlady had looked us up and down giving us that church-lady eye, but after Glory had talked to her for a while, sounding as haughty as possible, the landlady let us stay even though she didn’t seem to like the way we were dressed. And the next week the landlady was mad at us again because Glory was prancing around the house in her bra and panties.

“I ain’t running no whorehouse,” she said.

“Ain’t nothing but women in here,” Glory said.

“I ain’t running no whorehouse,” she said again.

Glory stood straight-backed with her hands on her hips, her breasts poked out like two puny Irish potatoes.

The landlady slammed the door.

I was sitting on the couch flipping through a magazine.

Glory shook her fist at the closed door.

“Don’t pay her no attention,” I said.

To the right of the living room was another small room and beyond that glass doors that let out onto a small patio. A small feeble tree seemed to be trying its best out there in the dingy yard, and beyond that, sheets flapped on a line in the dusty sunlight, and beyond that, brick buildings for miles and miles.

I’ve always been blackberry black. Glory was the color of poplar. She was a thin sapling of a woman but had hips on her that all the men seemed to like. She had thin lips and a thin nose that drew up her face into one sharp point like a pencil. I suspected she was mixed, but we never spoke about it. She had long curly hair that she kept pulled back in a bun unless we were going out. She was thirty but looked older sometimes. Glory had lived a hard life and told me about it on nights after we came home from the clubs. She’d lie across the bed with all that black hair splayed across the pillow, staring up at the ceiling or looking at a place on the wall that she never moved from until she finished her story. Most times she’d be naked or in her bra and panties, looking like she was posing for a picture. When she spoke about the hardest parts of her life is when she looked the oldest. Sometimes she’d look off toward another space on the wall like she was seeing all those moments unfold again and she’d suddenly hush then say, “Ain’t nothing delivered to your doorstep.” And then she’d laugh and her chest would jiggle. “Hear me?” she’d say and I’d nod my head.

There wasn’t new singing work at The Spider nor The Pandora. Though we’d both been offered dance work again.

Glory knew a shop where I could get new dance shoes, so we walked.

A girl was singing in one of the houses we passed. The sound rose up on the wind and out of the brownstone and out of the window down to us on the air. This girl behind that fluttering window curtain was an odd bird whose song I craved. I walked slow and deliberate to try and catch every note. I wanted to tell Glory to hush. This moment felt important to me, like I had just discovered some world for the first time, but Glory kept talking and kept walking. Knowing that I’d miss the end of that song, that I’d never know how it ended, made me want to cry.

Glory mocked my slow walk and the look I had on my face.

I pushed into her shoulder like we were girls on a playground. I giggled.

We kept walking.

Three men in suits walked past us. One had on a felt hat like my granddaddy wore to church; I liked the way he looked. One was bald and short and reminded me of Squirrel Griffith back home, whose mother Miss Jean worked in the sawmill right alongside the men. The third one, the one I thought was the least good-looking, looked back, nodded his head and smiled.

He bowed and fanned out his arm like he was introducing us to the king of some great land across the waters.

Glory giggled.

He asked if we were going for a walk.

“That’s what feet for. Ain’t they?” Glory always had a smart mouth.

We all laughed. The one who reminded me of my grandfather looked down at his watch, excused himself and took off. I saw a wedding band gleaming on his finger. The remaining four of us coupled up. Glory walked ahead with the one that had a shaved head. He was cute just like Squirrel but was about a foot shorter than Glory. The least attractive one looked me up and down as if to say “You’ll do” then asked where we were going.

We all went into the shoe store. I chose a pair of strapped black pumps from the sales rack that I thought would go with any of the dresses that I would perform in. The clerk boxed them up. The man I had been walking with then chose a pair of pink-and-green leather spikes with glittering studs on them in my size and asked the clerk to box them up too. When he offered to pay for them both I let him, even though I thought the pink-and-green shoes to be too loud.

When we got outside Glory said, “Damn, it’s cold. Y’all want to come by for a drink?”

The short man cleared his throat like he wanted to call it a night but the other one said they’d like to; on the way back to our house, they slipped into a liquor store and bought two bottles of wine and then stopped and bought some cheese.

The men seemed impressed at first at the house, as if one of us could have owned the entire place. Glory lit the fireplace in the living room. A large velvet picture of a red rooster hung over the fireplace, and little gold ballerinas danced around silver trees on the mantel. Burgundy and white plates and novelty shelves hung around the walls. I almost laughed every time I looked at the decor. It made the place look like some rich white lady’s house.

“Make yourselves at home, gentlemen,” Glory said in somebody else’s voice. “I’m Miss Velvet Jones and this is Miss Cleopatra Mitchell, appearing at The Spider most Wednesdays.” She brushed off her skirt and jutted out her hip toward the short bald man. “Man, you gonna open up that wine or what?” She crossed her arms. “And what’s y’all’s names?”

The short bald man looked at his friend but didn’t answer her. The other one cleared his throat.

“Hello,” Glory said. “Hello! You brothers deaf?”

“Milton,” the bald one said. “Call me Milton.”

“Milton what?”

“Just Milton,” the other one said and he began to laugh.

“What are you laughing at?” I said.

“Nothing,” he said. “Milton’s just funny.”

“Oh, he is?” I said.

He stopped laughing and took a deep breath. “I’m Jeff.”

I had never met men like this. I hated men like this. I knew they were making fun of me—my cheap dress, my fake accent, my attempt at confidence. Even the spindly tree that was barely a tree at all was outside the sliding glass door in the moonlight reminding me that I was a fake in these moments. I was quiet while the three of them laughed. But when I had a glass of wine I began to laugh too and soon I couldn’t stop drinking or laughing and I didn’t care if I was real or fake. I didn’t care if I was just nothing.

“How old are you?” Jeff said.

“Twenty. Why, do I look older? Younger?”

“Knew you’d be legal,” Milton said. “Y’all always legal.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Glory said.

“Oh, Miss Velvet,” he said, and petted her leg like it was a dog.

“I can show you my driver’s license,” I said.

“No need to go that far,” Milton said, his voice loud as a revival preacher’s all of a sudden.

He stood and brought over the second bottle of wine and filled my glass again. He squeezed my hand and then said, “Girl, your hands are like ice.”

“She’s from Kentucky, down South,” Glory said. “Always freezing. The girls at the club call her Miss Cornbread USA.”

“Kentucky’s not really the South,” I said.

Glory laughed. Then shook her head and dropped it as if she was making fun. “Shame,” she said.

“Well, I hope you don’t just take that off those women,” Jeff said.

He looked me up and down again but tried not to make it sexual. He didn’t pause long on my breasts or thighs, but I knew he saw everything. He was the perfect gentleman and listened to everything I said with his head cocked and his eyes squinted into mine. He heard the Kentucky in my voice then even if he hadn’t heard it before. I saw him look away and smile over his wine glass as if he knew everything he needed to know about me in one moment.

He asked me how long I had lived in the city, and I said, “Two years.” Then we talked about the club and how I got started singing.

“Church?” Jeff said.

“That’s how most of us got started.”

“Of course it is,” Jeff said.

“That’s enough talk about work,” Glory said. She looked bothered. “Y’all tell us something about you. What y’all do?”

“I work for the government,” Jeff said.

“A gov-ment man,” Glory said. “You never know when you might need one. And Mr. Milton, you must be on TV or something the way you acting. You some kind of actor?”

Milton cleared his throat again and said it was getting late and that they should go.

“I wish we could catch your show tonight,” Jeff said, “but we need to catch the train. Big day tomorrow but let’s do this again. Miss Mitchell, can I take you to dinner?”

I wrote down my phone number back home before I caught my mistake.

“Sorry, that’s my mother’s . . .”

“No problem,” he said. “I understand.”

We walked them out to say goodbye. And somehow I felt almost happy enough to skip. I blamed it on the wine because still inside of me was the same hurt throbbing like a robin against my ribs.

We went back into the living room and heard the landlady stirring around in the other parts of the house.

“She’s about to get after us again,” Glory said.

We listened for her, but she passed the door without coming in.

“Old bitch,” Glory said.

I didn’t say nothing.

“You got along with yours,” she said. “Mine was an asshole.”

I got close to the fire and thought about November and the smell of leaves burning in the backyard and the warmth of my feet next to a coal-burning stove.

“He thought I was too old,” Glory said.

“I didn’t like neither one,” I said.

“Neither one,” she mocked my accent, drawling out the words like a made-for-TV Southerner. “You didn’t have no problem giving out your phone number. Can’t blame you though. He got some money. Both of them do.”

“You shaking again?” she said. “You the coldest woman I ever seen. Get my coat and pull it over you. I’ll turn the heat up.”

The coat smelled like a sweaty horse and mothballs.

“Randall gave me that coat,” Glory said. “He’s that kind of man. He don’t give me much, but when he gives me something you can bet it’s not gonna be something cheap.”

“He white?”

“No, I told you he ain’t white.”

She went on talking about Randall who wasn’t white. How she was in love with him and still saw him when she worked out of town. She said that he was breaking up with her but that he was doing it slow and that he did everything slow. She winked.

Glory went on talking, but I didn’t listen.

I was thinking about how cold the night would be walking to the club and how cold the back room would be while we changed into our stage clothes. It was always cold. And Fontaine Chambers hogging the makeup mirror talking about, “Open up the door, Country. It’s hot as hell up in here!” But I’d still be shivering in my shiny gold outfit with too much blue stuff smeared over my eyes, waiting for my turn on the stage. I liked Fontaine though because she had that dark girl roughness like Stella Bohannan who lived up on Claude Street, even though Fontaine wasn’t anywhere near dark as me. And the cold, Oh Lord, the cold. The way I’d shiver in my gold lamé blouse with my fat sticking out way over the sides. Josephine Carmine, the white girl, saying, “She ain’t missing no meals over here. Where’s my earrings? I need my goddamn earrings.” And it’s cold, so cold my feet ache in my new shoes.

Glory was right there with me chattering on and on, crossing her legs and uncrossing them, but I was making my way home and back here again and again, turning memories over and then holding them up so I could see them better.

Months ago I watched all these people through the cab window—hundreds, no thousands, of them—all scurrying this way and that, to the subway, in and out of stores, going by buildings reaching up toward the sky where trees should have been. All these people with the same frowning expressions on their faces in a hurry to go somewhere, piling out into the streets, obeying the flash and beeping horns. I am not going to like this place—not going to like this madness—just want some peace and quiet— “You’ll get used to it,” Mama said. “A body can get used to anything after a while . . .”

“Let’s finish it off.” Glory poured us each one more glass of wine and we sipped it. She looked at herself in the mirror and sucked in her stomach.

“Looking old,” she said and poked at the corners of her eyes. “Old ass.”

“I’ve got a cousin who’s never seen the city,” I said. “She keeps asking me what it’s like up here.”

“Well, you know all about it now so why don’t you tell her,” Glory said. “You got enough to pay your half of the rent this week?”

“I should.”

We figured it up.

I had a little money saved up and Mama was supposed to send me a check for Christmas. I was sure she’d send it earlier if I needed it.

“Only three more weeks to hustle at this club,” Glory said.

I nodded.

“Girl . . .” Glory said and kept talking, but I was home again.

Up on the mountain, in the woods, behind the house. The moss between my toes, the earth as I knew it below me, small and compact as a girl’s playthings—a tiny house with a chimney of smoke, a swing connected to a hickory tree, a garden, a smokehouse, the hippy curve of green hills and the gentle dip of small valleys. A tiny creek cutting through the center of it all.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.