Snake and anatomical details (1847), hand-colored lithograph from the Book of the World

Buh Black Snake in New England

By Benjamin Anastas

A prep school teacher, Walker Percy, and the power of Gullah folktales

T

here are certain lines in Walker Percy’s novel The Second Coming that I can only hear in Mr. Myers’s droll, curvaceous baritone. It was startlingly clear, his voice—drilling right into the center of the mind and making things awaken there. Lines like, “Is she a gift and therefore a sign of a giver?” Or, more urgently for Will Barrett, the novel’s main wayfarer and, at least to me, Mr. Myers’s doppelgänger: “Is it too much to wonder what he is doing there, this pleasant prosperous American, sitting in a $35,000 car and sniffing cordite from a Luger?” I was a sophomore in high school in 1983, the year I read the novel in Mr. Myers’s most popular English class, an elective with the weirdly clunky name “The Hero as Rebel-Victim.” It was the closest thing we had at my all-boys prep school to a subversive class; in our school ties, button-down oxfords, and navy jackets, we read J. D. Salinger aloud and underlined all the tepid, antiquated curses in ballpoint, tucking the maroon paperback edition of The Catcher in the Rye in our outer pockets so the top showed while we slouched across the campus. Our suburban jaws dropped, exposing all manner of expensive braces, bands, and retainer systems, at the violence and privation that Richard Wright recounts in Black Boy—at least in the first section of the book, “Southern Night,” which was the whole and sum of Black Boy in mass-market editions in the 1980s. (The second part, “The Horror and the Glory,” wouldn’t be added back until the early 1990s.) And, of course, there was Camus’s The Stranger and Meursault’s stylish indifference to the societal virtues our parents were paying so dearly for us to steep in. Lord bless this food to our use and us to thy service, we all mumbled before we sat down for lunch in an eruption of scraping chairs. Steep in it we did, from the speeches we half-listened to in morning chapel, to the swarms we fought through to grab a stack of cookies and a carton of milk at our mid-morning break, to the afternoons we spent training for future success on the terraced playing fields. Mr. Myers’s classroom was that other place, where we steeped instead in discontent and its higher mysteries, the consolations of being alone and apart.

“[I]t is possible to make the case,” Percy writes in The Second Coming, and again I hear the words in Mr. Myers’s sonorous voice, “that for some time now life has seemed to become more senseless, even demented, with each passing year.”

Mr. Myers was an ideal guide into the literature of existentialism and doubt, though on the surface he could have been mistaken for one of the soldiers of school, family, and tradition who more commonly guided our education in the vinyl-sided sprawl outside of Boston. He was “old,” or at least he seemed that way to us—in his early sixties—with his neatly trimmed gray hair and orthopedic shoes, his gangly athlete’s solitude as he loped about his business. He dressed impeccably every day, usually in a tweed jacket and a silk repp tie, either in the Princeton colors—he was class of ’43, I’ve since learned—or our own school’s deep maroon and navy blue. Mr. Myers was from the South, New Orleans and Savannah, to be exact, and his easy drawl, somewhat flattened by all his years in New England, could be transfixing. He seemed like the kind of English teacher who kept his long unfinished novel manuscript buried in a desk drawer and who grew restless and dreamy when he finally relented to protocol and attended a faculty meeting.

All kinds of rumors followed Mr. Myers around campus, most of which, it turns out, had some basis in fact: that he was a ferocious tennis player who hated to lose; that he was on his third wife, or maybe it was his fourth; that he’d served in the Marine Corps in World War II and had been the white commanding officer of an all-black unit in the Pacific Theater. But the thing I remember most about Mr. Myers as a teacher had nothing to do with the books we read in his class or the sparse, vague comments I remember him leaving in the margins of papers, at least those he chose to return. On Friday afternoons, when the winter sun beamed too bright off the snowcover of the courtyard and the whistling of the radiators threatened to lull everyone to sleep, Mr. Myers would tell us to put our books away, then he would reach into a leather briefcase and pull out a sheaf of curling, smudged papers.

“I want you to listen now,” he would say with a certain sternness in his voice. “This is an oral tradition. These stories came from Africa with the first slaves who were brought to work the rice plantations on the Georgia coast. The Carolinas, too.” His eyes flashed up from the typescript he was holding, a collection of Gullah folktales. “I’m going to read one aloud and let you figure it out on your own. You’re smart enough to understand. At least you ought to be.”

We snickered at his insult. There was always a snicker—we had more varieties than a murder of crows. Mr. Myers heard it, but he didn’t care. He was one of us, in a way. Except for when he read the Gullah stories. In the Gullah language. Then he was a man with depths we couldn’t fathom—a pleasant prosperous American, like Will Barrett in The Second Coming, who knew things that were buried: in the language we use without giving it a thought, in the theologies that instruct our lives and shape our world, in the ancient caves beneath the manicured golf courses of the Carolina exurbs and the secrets they preserve, the Confederate hideouts and stalagmite formations. Mr. Myers had lived. And we hadn’t, at least not in any way that mattered. Not yet.

It’s astonishing to me now that Mr. Myers would carry these Gullah tales in his briefcase at all, let alone that he would devote regular class time to reading them aloud for an audience of white private-school chuckleheads who knew more about Terry O’Reilly’s career fight record for the Bruins than they did about slavery in the U.S., or, even more certainly, the oral culture of the Sea Islands and its preservation.

“This one’s called ‘Buh Black Sneak Git Ketch,’” Mr. Myers said.

More nervous snickering.

“I don’t have to read this,” he warned us, looking up from the sheaf of papers again. “I can give the next person who laughs an hour and ask the rest of you to leave . . . ” (Getting “an hour” was the equivalent of detention at our school. There was some honor in getting an hour, but that was outweighed by the morning practice or the weekend game you might be missing. There was no honor in letting down your teammates.)

The radiator kept on whistling.

“I’ll continue, then,” he said.

Mr. Myers leaned back in his creaky office chair, popped a lozenge in his mouth, and started reading.

Myers in his Marine uniform; he joked in an accompanying note to his family that he had “a slight innovation on the upper lip.”

Myers in his Marine uniform; he joked in an accompanying note to his family that he had “a slight innovation on the upper lip.”

Will Barrett begins to come apart on the golf course, first with falling spells on the fairway that bring on flights of desire and heightened consciousness, then with the appearance of a nasty, persistent slice that carries him into longleaf pine forests and backyard barbecues in search of his errant Spalding Pro Flites. A retired Wall Street attorney with an enviable six handicap and an inherited fortune from his late wife, Barrett once felt at home with the race jokes and the investment schemes that make up the banter on his regular foursomes with other men from the Linwood Country Club. But, all of a sudden, the bottom seems to be falling out of this reality and he finds himself in a kind of internal exile in a land of upscale retirement developments, church functions, and award ceremonies for the local Rotary Club chapter. What’s different now about Will Barrett? He sees.

Now in the middle of this pretty Carolina fairway in the sweet high mountain air, as the sky darkened and the acrid smell of rabbit tobacco rose in his nostrils, he fell down again, but only for an instant. Or perhaps he only stumbled, for the next thing he knew, the electric cart hummed up behind him and there was Vance.

No, he did fall down, because he seemed to see and smell the multicolored granules of chemical fertilizer scattered in the bent Bermuda.

It’s not just the bent grass and the fertilizer that Will Barrett sees for the first time while he’s playing a round with his friend Vance. It’s his life and the “secret love of death” that’s always hung over it like a tropical depression; he’s transported, during one extended fall sequence, to a swamp in Thomasville, Georgia, where his father, in the grip of a death spell of his own, tried to kill him with a twelve-gauge shotgun on a childhood hunting trip. “Twelve years old,” Percy writes, “he grew up in ten minutes.” There’s also his daughter, Leslie, described as “a tall sallow handsome dissatisfied nearsighted girl”—five adjectives in succession! Don’t try that at home!—who is conspiring with Jack Curl, a “sweaty Episcopal handyman” from the church, to spend her mother’s remaining fortune on the establishment of a residential love-and-faith community “lived according to the rhythm of God’s own liturgical year.” In case we needed any reminding:

[They] lived in the most Christian nation in the world, the U.S.A., in the most Christian part of that nation, the South, in the most Christian state in the South, North Carolina, in the most Christian town in North Carolina.

So it makes perfect sense that, in the novel’s inciting event, Will Barrett descends into the Lost Cove cave with a flashlight and ninety-six capsules of Placidyl, a sedative and anti-insomnia medication, in order to, as he puts it in a long rambling letter, “settle the question of God once and for all.” The novel was published in 1980, and I expect that Will Barrett’s descent into the cave to find God—or to confirm God’s absence—among the bat colonies and the underground gravel beaches and the lairs where Paleolithic tigers once dragged their prey, was influenced by Bishop James Pike’s fatal retreat into the Judean Desert with his third wife and two bottles of Coke in 1969. (Joan Didion’s essay about the Episcopal Bishop of California and his spiritual fiascoes, “James Pike, American,” from The White Album, may be the most caustic thing she’s ever written.) Will Barrett’s test of God is no less of a fiasco: he scurries around the chambers of the cave dropping notes for an eventual search party that never arrives and rationing his Placidyl to carry him through the End Times. He gets a toothache after seven days, and his spirit crumples from the pain and resulting nausea. He revisits his past and suffers hallucinations as his descent continues; in one, he meets a Paleolithic tiger and lies down with it for the night.

“Is this the place for me?” the tiger asks Will Barrett. “Will I be happy here? Will the others like me? Will my death be a growth experience?”

Finally, Will Barrett suffers a truly catastrophic fall inside the cave, one that draws his scrotum “tight as a slipknot” and leaves him bruised and bloodied. He scrambles on his hands and knees for a passage out of the cave, until he discovers a “square hole” covered with vines that opens on another world; he falls through and lands in the interior of a greenhouse on old Judge Kemp’s abandoned estate in Linville. There, a young woman with no memory at all attends to him, bathes him, and feeds him oatmeal. This is Allie, an escaped psychiatric patient with a scheming family of her own. She doesn’t know if she is Will Barrett’s daughter, or his lover, or both—and she doesn’t particularly care to make distinctions. This is where the novel’s two halves join together, and it’s such a startling and wrong-seeming and yet bizarrely perfect turn of events that I wondered, when I picked up The Second Coming again and read it for the first time since Mr. Myers assigned it, How did he get away with teaching this?

I’m going to go out on a limb and say that I doubt there is a single high-school class in New England—or anywhere else, I would imagine—where The Second Coming is being taught in the year 2020, a number that neatly embodies the hardness of our times and the lack of mercy we extend to everything we read, either in print or online. Walker Percy, who died in 1990, has entered the “eclipse” stage that claims almost every American writer and their reputations after death. His first novel, The Moviegoer, published nineteen years before The Second Coming, certainly has its acolytes—Paul Elie celebrated the book for its ambling, spirit-led depiction of a society “whose every aspect seems mediated, contrived, statistically anticipated, manipulated in advance” in a recent New Yorker essay—but what about The Second Coming? On my own rounds in the classroom teaching literature to undergraduates and writing to MFA students, no one had even heard of it. So I turned back to The Second Coming last year with visions of revival, of slipping into my own orthopedic shoes (more likely, I’d just settle for a pair of sneakers) and teaching it in one of my classes. But now that I’ve read The Second Coming again in our time, I’m not so sure.

First, there’s the problem of Will Barrett and his place in the order of the universe. For white male writers of a certain generation, and arguably any generation, it’s taken on faith that the world is your dominion and that your protagonists are there to stake a claim on it. Early in John Updike’s novel Couples, the suburban sex parable that landed the author on the cover of Time magazine in 1968, Piet Hanema, a home builder, is thinking back to the way his courtship with his wife, Angela, coincided with her father’s steering work his way to help establish his business—and their marriage. “Nine years later,” Updike writes, “Piet still felt, with Angela, a superior power seeking through her to employ him.” I’ve never seen a clearer example in fiction of what we now call “white entitlement” and its spiritual dimensions. And there are similar forces at work with Will Barrett in The Second Coming, assigning a depth and a significance to his soul-sickness that turns the other characters, particularly women, into members of his support team—Allie most of all, but also his daughter Leslie; Allie’s mother, Kitty, his former girlfriend, who is referred to by one golfing partner as “the best-looking white girl I ever saw”; and the usual cast of Dilsey-like black women who endure and show their otherworldly humanity at key plot points.

There’s a passage I have no doubt I appreciated and probably even underlined with vigor as a teenager at my all-boys school outside of Boston, but now it leaves me puzzled:

Why did God make ugly girls? It is hard to say. That was God’s affair. But one thing he, Will Barrett, could do was make ugly girls happy. Then was that why God made ugly girls? So that selfish people like Will Barrett could make them happy and feel less selfish, do two things at once?

It isn’t the substance that gives me pause, or even the breeziness of the use of a categorical distinction that in itself is ugly—it’s the complacency and ease of Will Barrett’s “That was God’s affair” and the smugness of the theological treatise that follows. The reversal in the final line (“So that selfish people like Will Barrett could make [ugly girls] happy and feel less selfish”) is meant to disarm us and signal the narrative’s self-awareness. Sure, Will Barrett is basically an asshole with a copy of Fear and Trembling on his bedside table. But he knows that about himself. Isn’t that enough to absolve him in our eyes? This is a work of fiction, after all. Percy tries his best to play a similar double-game with the novel’s racial banter, in particular a series of jokes told on the golf course: the character who most often tells the jokes, Jimmy Rogers, is meant to represent a Southern “type,” thoughtless in his fealty to expressions of white dominance. But the jokes themselves are often recounted in full in dramatic monologue, and the punch lines land with a cymbal crash. We are meant to laugh along with the likes of Jimmy Rogers even as we recognize his malignancy. I can’t do it, though. And I’m sure I’m not alone. The jokes exist, and perhaps there’s some value in recording them in a novel, the airing out of the collective unconscious and being true to the casual cruelties of the world these characters live in, etc. But they aren’t funny. They’re just race jokes from the country club faithfully transcribed. That’s it.

I’m sorry, Mr. Myers. There is a lot I love about The Second Coming: the way Percy shows how our appetites for the ineffable and the everyday are coded in the same language and overlap more than most of us would like to admit; his brilliance at capturing the shapes of speech; the grace he sees in even the most rank forms of human folly. I can even see how reading the novel when I did may well have helped me on a path to becoming a writer. How else can I account for the persistence of the church and the pursuit of God in my writing, when I was raised in an unreligious home and spent a grand total of about eleven minutes inside houses of worship when I was growing up? But I don’t think I can teach the novel in any of my college classes, not in 2020. There’s too much I would have to try and justify or explain away. That might be a loss for my students. It certainly isn’t good for The Second Coming and its afterlife. But that’s God’s affair, isn’t it?

A photograph of the 23rd Marine Depot Company, which Myers commanded, found among his letters.

A photograph of the 23rd Marine Depot Company, which Myers commanded, found among his letters.

Let’s start with the marriages: there were five in all, a fact omitted from the obituary for John Anderson Myers Jr. (“Known all his life as Jack”) that originally ran in the Savannah Morning News on April 24, 2007, and that has achieved eternal life in the database at Legacy.com. When I look it up on my phone now, there is a button for sending flowers. Who would get them? This is just the kind of tear in the reality fabric that Will Barrett would have used as an excuse for opining about the legionnaires of death in Cold War–era America and the failure of our institutions to deliver us from evil. (“Show me that Norman Rockwell picture of the American family at Thanksgiving dinner,” thinks Will Barrett in The Second Coming, “and I’ll show you the first faint outline of the death’s-head.”) Five marriages. That’s almost Norman Mailer territory. It explained, or at least I thought it might, some of the sense I’d had in high school that Mr. Myers had lived more than the rest of my teachers, had earned a special status that went unmentioned but was understood. Was it suffering? There are people who are set apart, almost by force-field, and when I thought of Mr. Myers, he was on another plane. There with his Walker Percy novel and his Gullah stories. There with the shadows of all his ex-wives. It was this apartness of his that brought me to research his life and to track down his daughter Sally in Massachusetts. When I asked her at her dining room table what she thought about her father getting married five times, she took a long, plunging pause and said, “I think my father had a difficult time being close to anyone. He was charming and he took a lot of pleasure in life. But it always seemed like he was somewhere else. He was just . . .”

“Absent?” I suggested. It was the first word that had materialized. Mr. Myers had been a gifted teacher, but when you approached him at his desk or passed him on a campus pathway, he tended to be elsewhere. Or an even better word: “abstracted.” He seemed to be looking through the world and its dailiness to another place that only he could see.

“Yes,” Sally said. “You could say absent. I mean, he tried. But I didn’t get to know my father until much later in life.”

The obituary helped dispel some of the mystery about Mr. Myers and fill in the gaps in what I’d known about him, or thought I had. Born in New Orleans on June 4, 1921, to parents both from Savannah. Educated in Savannah public schools before shipping up north to attend boarding school at Lawrenceville in New Jersey. Enrolling at Princeton in 1940 and graduating on the accelerated wartime program that became standard at four-year colleges and universities after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Along the way, he lettered in track and 150-pound football. The obituary even confirmed the rumor we’d all heard about Mr. Myers’s wartime service: the unit in the U.S. Marine Corps he’d commanded, the 23rd Marine Depot Company, had been primarily black, and this experience had “instilled in him a life-long commitment to civil rights.” Granted, the source for the information gathered in his obituary would have been his own family, and the myth-making power of the average family is Homeric, but still: this seemed like a key piece of information in understanding the presence of the Gullah stories in Mr. Myers’s briefcase, and one of the reasons why he took the trouble of reading them aloud to us on those Friday afternoons in class. The obituary also led me to his daughter Sally, and I drove to Massachusetts early one morning last fall to meet her in person and look at the contents of some storage boxes of her father’s that she’d recently picked up from his ex-wife Lucy—his second wife, and not Sally’s mother—on Martha’s Vineyard.

When I arrived on Sally’s doorstep and followed her into the front room of her warm, cluttered house in a suburban neighborhood near South Dartmouth, I saw that she had already unpacked the boxes and spread what she’d found out on her dining table. There was a scent in the air of recent baking, as if a pie had just come out of the oven—Sally runs a catering business that specializes in desserts and baked goods. I sat down at the table and started looking through the neatly stacked letters, photographs, and papers, while she went off to find the last remaining storage box. The letters drew me first. There were stacks of them. They smelled of attic and mouse nests and sun-bleached windowsills. Some of the letters had been nibbled at the edges or were missing what looked like a bite out of one corner. They were letters that Mr. Myers had sent home to his father—his mother had died early, when he was still a boy—from Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, where he’d done his training and been stationed first, and then from Hawaii and Guam. You could see the jagged edges where Mr. Myers’s father had cut into the envelopes with a letter opener, probably in haste, and many of the letters had much more recent writing on the outside. Notes like, IMPORTANT LETTER! or, ABOUT WHAT I WANT FOR THE FUTURE—IN THE WAY OF A JOB AND THE CHANCE TO USE ALL OF MYSELF. This is Mr. Myers’s own handwriting, cataloguing the letters he’d written home to his father in 1944 and 1945 from a much later time; the hand is shakier and the pen is ballpoint.

“Dear Daddy,” the letters all begin. At first they are written on embossed U.S. Marine Corps stationery from Camp Lejeune, which is surprisingly elegant, given that it was issued by the military—but later in 1944, presumably when this store of paper ran out, the letters switch to standard blank stationery or plain lined paper. Mr. Myers’s cursive is sharp and fluid, almost without flaw, though the lines start slanting downward as the letters stretch on and the pages accumulate. Sally would go on to tell me that morning how Mr. Myers had never gotten along with his father and that they’d had a lot of conflict about the Old South and its traditions, particularly when it came to race. “He used to tell the story,” she said, “of the time he brought a black friend home from school in Savannah and walked him through the front door. That was not allowed. Since he was black, he was supposed to use the back door to the kitchen. There was a big fight about it. I think my father never forgave him.” In the letters that I read at Sally’s table there is a constant tension between the wish to be a dutiful son and share his news from the Pacific with his father—what details he’d been assigned as a supply officer; what life was like in this exotic place and the activities he and the other Marines were doing to pass the time; the friends from Savannah he’d run into by chance in the “chow” line—and his not-so-subtle attempts to educate his father about the men in his unit and their right to equal treatment under the law.

There are two letters that stand out from the rest. Both are from early in his time in the Pacific, in May of 1944. In the first letter Mr. Myers apologizes for being out of touch for so long and explains that, after they waited weeks for the order to ship out from Camp Lejeune, the word suddenly came down that they were to leave, fully equipped, in forty-eight hours.

Well, of course, things were pretty fouled up and everyone was running around like mad. I, being property officer, stayed up all night three days in a row getting our property squared away for shipping with us—a whole warehouse full of it. Somehow or other we managed to get on the train Wednesday afternoon. It was a wonderful relief when the train pulled away amid much excitement, which, I’m afraid, I was too exhausted to appreciate fully. It was quite a send-off, though—bands and everything.

They were on a troop train carrying two Marine companies: the 23rd and the 24th. The whole train was Pullman, Mr. Myers reported, meaning that it had sleeping cars. The officers all had separate compartments, and they extended the same privilege to some of the NCOs, or noncommissioned officers. The officers in Mr. Myers’s company would have been white, the NCOs black. There is no mention if they were assigned the same sleeping compartments, or if the NCOs slept in the “colored” compartments that were common in U.S. railways under Jim Crow and inferior in every way. Mr. Myers goes on:

We came by way of Birmingham, Memphis, Pine Bluff, San Antonio, El Paso, Tucson, Yuma, Los Angeles, and finally, Frisco. The thrill of going through Birmingham I shall never forget. The whole negro section seems to be right along the railroad tracks and it seemed they were all there to wave at the train. Some of our NCO’s lived there, saw their houses, people they knew—it seemed that everyone got word of our train and was there to wave, salute, exchange greetings, though the train didn’t stop at the station. Just a wonderful feeling of friendliness throughout.

Our best ranking NCO was by me pointing out the spots of interest along the way—even the old hole where he used to swim. All along there were similar occasions on a minor scale.

While there were a few letters from Mr. Myers’s father in the stacks on Sally’s table, none of them were from this time in the war, and they didn’t raise the subject of race or of Mr. Myers’s growing consciousness of racism in the U.S. thanks to his exposure to the black Marines in the 23rd. So there’s no way of knowing what he thought about these glimpses of the troop train being met by waving crowds as it passed through the black neighborhoods of Birmingham, or of the similar crowds Mr. Myers describes gathering when his men got off the train to exercise and to drill. “Colored Marines are quite a novelty,” he wrote to his father. “We amazed people from Birmingham to L.A.” It’s clear to me he assumed that his father would also have been amazed to see an outfit of black Marines emerging from their troop train in uniform to drill beside the railroad tracks. U.S. Marines were supposed to be white, weren’t they?

But there are hints throughout the letters that the conversation between them about race was full of conflict, and indications of a father-son rift that only widened the longer Mr. Myers stayed in the Pacific with his men. After that train ride west from Camp Lejeune, Mr. Myers had partly filled the time onboard the ship that carried them from San Francisco to Hawaii by reading Richard Wright’s best-selling novel Native Son, first published in 1940, and it seemed a turning point for him. He was radicalized.

Your comment on my attitude toward the colored race—I couldn’t help but be amused a little by the comment. I doubt it, but it’s possible that some day you’ll understand (meaning by you 95% of the perennial Southerners) that it’s not a question of there being a question with different sides to be taken. It’s simply that there exists a terrific problem the existence of which most people try to deny—a problem that must and will be (1) either solved or (2) exploded.

The problem he was referring to, he wrote, went deeper than prejudice and social custom. It was a “psychological” problem in nature that arose from primitive superstitions and the hatred of blacks on the part of whites.

The whole thing is built up on fear—a fear which—rightly felt at the time—has lasted since the days of re-construction, has been handed down and . . . persists today in the form of men like Senator Bilboa [sic] from Miss.—you should see some of his harangues. Some are unable to grasp the wholeness of the situation, others don’t want to, some can but still are afraid to back up what they know is true. I used to know all of this in theory only—now I know it in fact.

He goes on:

You would do me a great favor if in one of your spare moments you would purchase a copy of “Native Son” and if nothing else read the introduction. It’s by a negro author, I read it on board ship coming over, and nowhere else have I seen anyone understand and express the situation in its entirety as this man has. It’s something I’ve known but could never put into words as he has. I think it will give you a new understanding of their problem. Always remember that before anything can be done there’s got to be a complete change in the mind of the white South and about 75% of the rest of the country. Amen!

That was it. I was almost sure I’d found it: a conversion moment in Mr. Myers’s life, a dividing line between the “before” and the “after,” a record of the instant when the scales had fallen from his eyes. It had happened on a Navy ship, somewhere in the expanse of the Pacific. He’d been through Birmingham with his men and watched the crowds gathered at the tracks to send them off to war. He’d felt the ocean rolling beneath him with a book in his hands, Native Son by Richard Wright. That was the birth of his life as a teacher. It was why he kept the Gullah stories in his briefcase and pulled them out on Fridays. But what about his own writing? The novel manuscript I’d always assumed Mr. Myers had stashed away in a desk drawer and messed with on school vacations or during the long summer break? Didn’t that train trip he’d taken with the 23rd from Camp Lejeune to San Francisco belong in a novel?

I asked Sally about it. There was no novel. It didn’t exist.

“My father didn’t even read that much,” she said. “I bet that surprises you.”

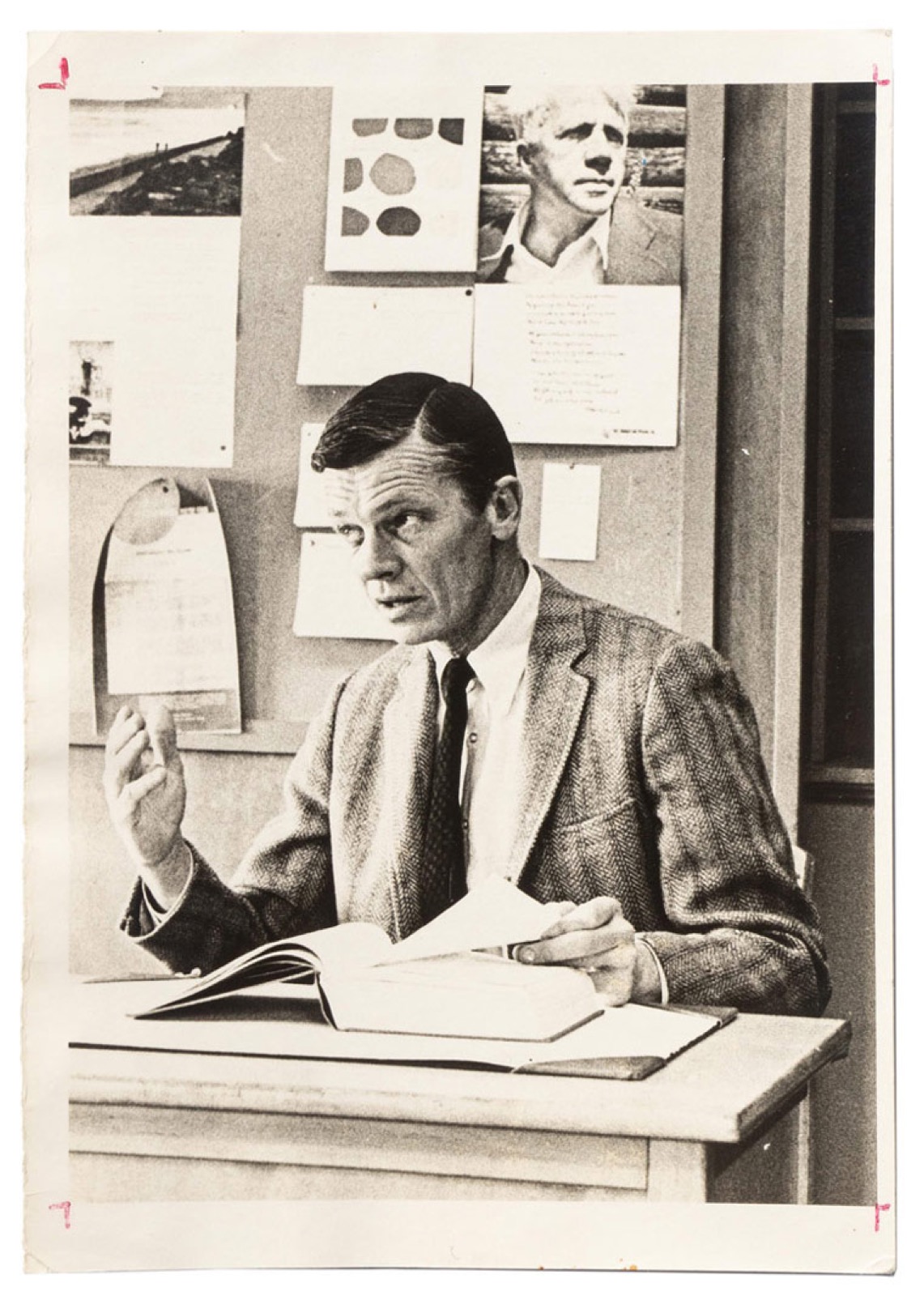

Mr. Myers in class, beneath a photograph of Robert Frost.

Mr. Myers in class, beneath a photograph of Robert Frost.

I’m almost certain that the version of the Gullah animal tale “Buh Black Sneak Git Ketch” that Mr. Myers read to us in “The Hero as Rebel-Victim” comes from a recording made for the Library of Congress in 1949 by an amateur folklorist named Albert Henry Stoddard Jr. Stoddard lived in Savannah, the liner notes for the three-LP collection Animal Tales Told in the Gullah Dialect inform us, and he “grew up as a child with the Gullah Negroes” on Daufuskie Island, one of the Sea Islands where the Gullah language and culture survived in the years after slavery. In an interview conducted at the same recording sessions in 1949, Stoddard describes how increasing contacts with the outside world and a greater access to education had changed the Gullah language that he remembered as a child, and it was only rarely, when the elders in the community were “excited,” as he put it, that they “lapse[d] into the old Gullah.” The recordings for the Folklore of the United States project were meant to preserve the animal tales in a form “as close to the original as it now seems possible to come,” the liner notes explain, though Stoddard’s exposure to them, admittedly, was “second hand.” Albert Henry Stoddard Jr. was white. His ancestors on Daufuskie Island were slaveholders. The children he grew up with on the island were the descendants of slaves once owned by his family. This makes the Gullah animal tales he narrates on the records for the Library of Congress a uniquely complicated document of the culture of slavery and its aftermath in the South. Authentic, no. Stoddard’s rendition of the animal tales is his own. But if his recordings of the lesser-known stories in remembered Gullah are the only versions of them on record, then they are probably the closest thing we have to the originals.

The story itself is straightforward enough: Black Snake goes into Rabbit’s yard one day and eats one of his children. This upsets Rabbit, who goes out to get some boards and builds a fence around his yard. Once the fence is built, he calls his children together and warns them never to leave the yard so they’ll be safe from Black Snake.

One of the boards in the fence has a knothole close to the ground, and every day, Black Snake comes to the knothole and peeps in to see if any of Rabbit’s children are close. But he doesn’t trust his luck enough to go in after them, since Rabbit could set a trap inside the fence and catch him.

Rabbit doesn’t think he’s lucky enough to keep Black Snake from coming in to catch his children either, so he sets a series of traps to try and get him. Black Snake is too smart, though, and doesn’t fall for any of the traps.

Rabbit goes to the barn where the Hen keeps her nest, and while the Hen is away, Rabbit takes two eggs. He puts one of the eggs by the knothole on the outside of the fence, and the other egg by the knothole inside the fence.

Just then Black Snake comes and sees the egg on the ground. Someone left an egg here, he says aloud, and he eats it up. He looks through the knothole and he sees another egg inside the fence. There’s another egg in there, he says.

Black Snake looks all over but doesn’t see anyone, so he pushes his head through the knothole and swallows the other egg, too.

After Black Snake swallows both of the eggs, there are bulges in his body where the eggs are stuck. One of the bulges is outside the fence and the other is inside the fence. Black Snake is stuck in the knothole. He can’t go inside Rabbit’s yard and he can’t get out again.

Rabbit has been watching him the whole time. When he is finally sure Black Snake is stuck at the knothole, he calls his family outside and they gather around Black Snake.

Why don’t you come in the yard? Rabbit says to Black Snake. All my children are right here. You should come and eat them. Didn’t you say you were too smart to fall into my traps, Black Snake? This makes Black Snake so angry that he twists and he coils, twists and coils, until the sharp edges of the pine knot in the fence cut him almost in two. He dies right there, and he never gets to catch and eat any more of Rabbit’s children.

Here are the opening paragraphs of Stoddard’s “Buh Black Sneak Git Ketch,” the same version of the story that Mr. Myers read to us in class:

Buh Black Sneak gone een Buh Rabbit ya-a-d one time en ketch one uh Buh Rabbit chillun en eat um, en dat bex Buh Rabbit tummuch and he gone git some boad en mek tight fench roun and roun de ya-a-d, en tell de chillun dem say e ain none uh dem fuh go out da ya-a-d none tall.

One uh de boad wuh low tuh de groun bin ha one knots hole een um, en ebby day Buh Black Sneak does come peep e yie troo de hole fuh see ef one uh Buh Rabbit chillun dey close de hole. But e wouldn’ trus e luck fuh come een. E faid say Buh Rabbit might uh pen um up een day.

Stoddard’s voice in the Gullah recordings is higher-pitched, more nasal and thinned with turpentine, than Mr. Myers’s voice when he read “Buh Black Sneak Git Ketch” to us—or at least the voice that I remember. He was less hurried in his delivery than Stoddard is, too. More at ease as a storyteller. But these are minor points of style. In substance, the readings were the same. Mr. Myers was a white Southern man of a particular experience and a certain age adopting the voice of a Gullah-Geechee storyteller and reading a folktale with its roots in a faraway place that was full of feints and disguises, surface meanings and encoded messages, the expression of a culture that survived by an act of transmission that was permitted on the Sea Islands only because the slave masters were absent for much of the time, as they feared contracting malaria from the swamps and the flooded rice fields. And only then the stories survived because they were about animals and their natures, not slaves and the slaveholders who owned and controlled them, the conditions of living without freedom, liberty. As scholarship of the Gullah-Geechee animal tales has pointed out, the storytellers could impart important collective knowledge and the means of survival as a community in stories that were engineered to be dismissed as harmless by an audience that overheard—while the primary audience, the recipients of the tale, understood the meaning of the stories implicitly. It became their shared secret.

I have forgotten so much of what I learned in high school. It is years ago now, a time of history that has passed. I used a typewriter in 1983. Ronald Reagan was president, and Yuri Andropov, for the blink of an eye, was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. When Mr. Myers died in 2007, he was living on Wilmington Island in Savannah, a stone’s throw from where the Stoddard family once had its plantation on Daufuskie Island, across the Savannah River in South Carolina. I hardly remembered Walker Percy’s The Second Coming when I read it for the second time last year. A cave? A greenhouse? Somewhere along the way I lost my sense of Will Barrett as Hero, let alone as Rebel-Victim. There are times when I think that I learned one thing in high school, one thing only. And I learned it from the place in “Buh Black Sneak Git Ketch” when the snake sees the egg, the first one Buh Rabbit lays out for him outside the fence, and he says aloud, in Mr. Myers’s voice, “Eh eh, someone don lef one aig yeah.” Rabbit knows the black snake’s nature. The tale has painted Buh Black Snake black. But he’s white. And he’s greedy. And he doesn’t know his own nature. Not like Buh Rabbit knows it, because he’s lost a child to the snake’s belly. This story was not meant for me. It wasn’t meant for Mr. Myers, either. But he read it aloud to us at a time in life when there was a chance that it could change us. And even now, I hear him.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.