COVID Kitchen

By Crystal Wilkinson

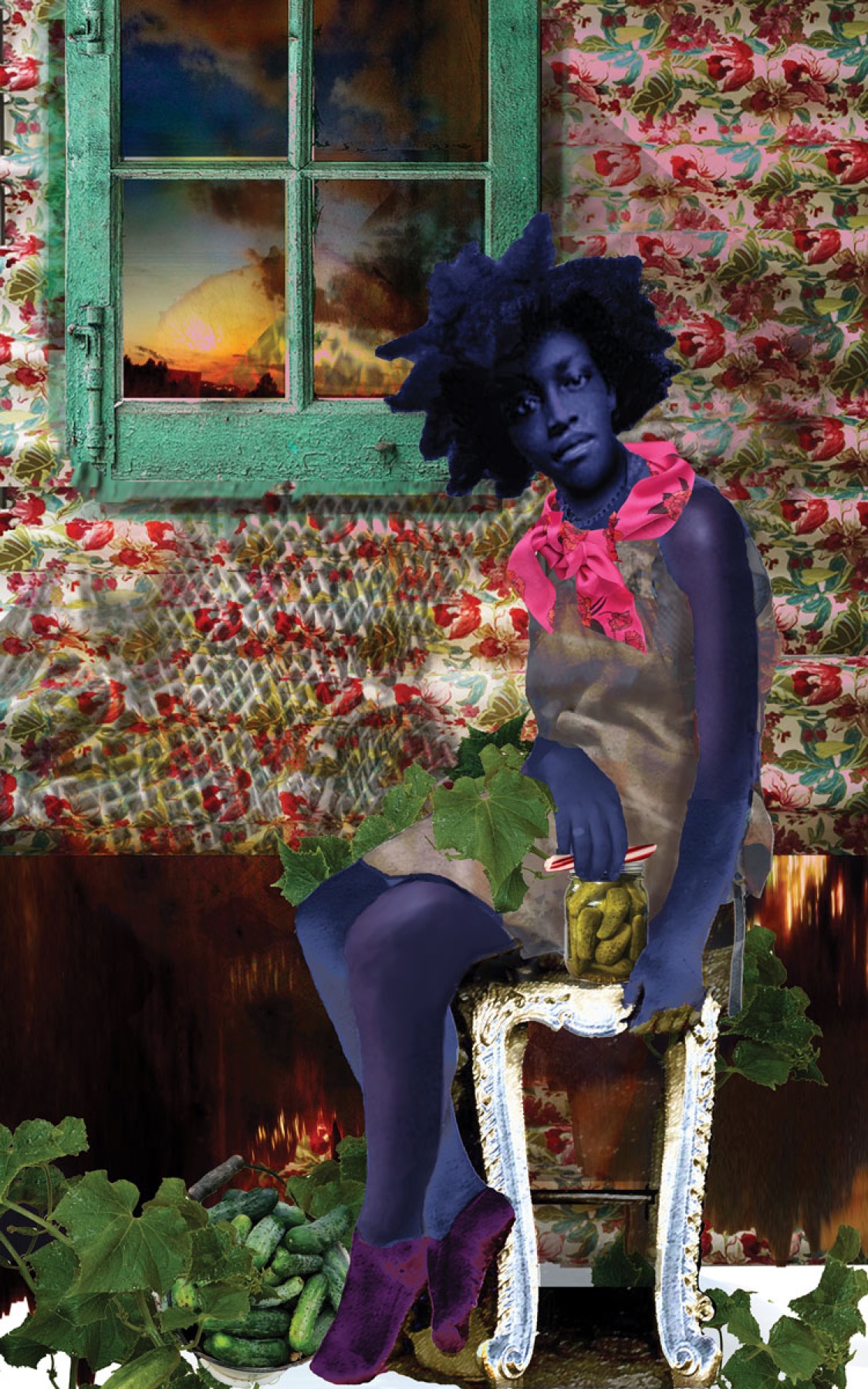

"Peppermint and Pickles," by Najee Dorsey. Courtesy of the artist and Arnika Dawkins Gallery

In March when the coronavirus descends on Kentucky, just as it has all over the world, spring is beginning to show itself. The front yard is a new green. My partner, Ron, sits in a wicker chair on our porch with his back to me “washing the groceries.” His dreadlocs fall forward across his shoulders while he works. The day is warm; he nods his sweet head to the music. “Salaam Peace” by Abdullah Ibrahim reaches back to me inside the house, and the jazz lends a calming hand. I’m readied at the storm door to assist with the sea of full bags that covers the porch, and the music takes me up, too.

My partner’s hands dip into the plastic bags, emptying them one at a time, placing the food in front of him in a semicircle around his feet. He sprays bleach water on each item and methodically wipes them down with paper towels, then places them in the “done” pile. The rhythm of the work soothes us both. We are accustomed to working our minds, but the bend and scoop of this methodical labor reminds me of the kind of work my grandparents did on the farm when I was a child. Bend and scoop, bend and scoop. Our work, in comparison, is easy, but the repeated movements are familiar and I’m glad my body remembers them. Sometimes we smile or hand each other more paper towels, but mostly we work in silence. Ron separates the onions, the bananas, the plums, the tomatoes, and I take them inside to swirl them around in saltwater in the kitchen sink. I hold the tomatoes up like a prize though I know they will taste like something tomato-flavored and not the burst of freshness of my childhood. I blot them dry with paper towels and put them away. I go back out to the porch, blot the cans, the boxes, hard plastic packaging. I think about the increase in our carbon footprint. Though I appreciate hired shoppers, my canvas bags lie unused and the shoppers don’t have time or inclination to make choices based on package waste. These are all pre-pandemic concerns. I place the groceries in a silver wheeled basket that belonged to my mother, stuff down my apology to the environment, and roll them inside the house to the kitchen. I think of my mother, my grandmother, my grandfather every time we do this. I stand in our kitchen straddled between past and present.

When I was a child, my grandparents went to Food World on Saturdays. My grandfather, Silas, sat in the car listening to the radio while me and my grandmother, Christine, went up and down the aisles to supplement the vegetables she harvested from her garden. We skipped the produce and focused on kitchen staples. My grandmother said store-bought tomatoes were the “awfullest thing you could ever put in your mouth.” She bought flour, sugar, yeast, rice, cereal, cornmeal, and a few canned goods depending on the season. Sometimes she bought cube steak, roast, or hamburger, but we usually bypassed the meat section. My grandmother’s brother, Uncle Addison, owned a slaughterhouse where we often picked up sausages, steaks, and roasts, and my grandfather had country hams curing in the smokehouse. But occasionally, I could get hotdogs as a treat, or my grandmother bought bologna or hogshead cheese because my grandfather liked them.

At the beginning of the pandemic, my partner and I were awkward in our routine (we still have cans of food that we can no longer identify because the labels were destroyed from washing too much), but there is a pulse to this now. We have quickly moved into our habits and the peace of isolation. Even after medical experts said groceries didn’t need to be disinfected, we’ve continued doing it. He works from home as a poet and artist. I now teach online. The summer of 2020 was to have been filled with travel and writing—California, Vermont, New York, and Washington State. This summer was to have culminated with a five-month leave from fall teaching to write, but instead, here we are at home, settled into a strange new routine of gathering the groceries and making them safe for our kitchen. Out in the world there is so much death. Inside, the tragedy makes us examine the past. I am always reflecting on family. I am thinking of how my mother, my grandparents might have coped with quarantine. My grandmother was the queen of worry-and-cook, a method which I

have inherited.

My grandmother kept a clean but cluttered kitchen, dish towels spilling from a cabinet, canned food jammed into the cupboard. Her kitchen was tiny and stuffed. She had an electric stove and refrigerator but also sometimes cooked on a small wood- and coal-burning stove that sat in the middle of the kitchen. She grew flowers on the windowsills. A glass jar of Devil’s Ivy snaked from one window to the next. She washed dishes in a galvanized tub, then poured the dirty dishwater on plants in the yard. She grew a large swath of daffodils near her clothesline. She called them buttercups. She made biscuits every morning for breakfast. Cornbread every night for supper. She made quick pickles and slow pickles from the cucumbers from her garden. She made relish from her tomatoes and bell peppers and onions. In my grandmother’s kitchen there was always work to be done. Before COVID-19, aside from holidays or special meals, work in my kitchen happened in the early morning before work or was squeezed in after work before bed.

In my front yard, the tulips and daffodils planted years ago peek their heads up, and I pay attention in ways that I haven’t been able to in years past. This year, in my slowing down, everything in the yard reveals itself to me almost in slow motion. Scraggly, brown patches of grass, the bushes growing up over the bedroom windows, the two fat rat snakes that nestle there in the branches. Sticks and branches left rotting from last year’s storm. The backyard is an overgrown wonder with squirrels and birds and mole holes. The far-left corner of the backyard is where I planted my first and only vegetable garden years ago as a first-time homeowner. Onions grow wild there, but mostly it’s a rectangle of overgrown weeds and remnants of rotting railroad ties. My grandmother would have called it a snake harbor. I am reminded of why I purchased the house, though, when I look out at the backyard, its expanse larger than most suburban backyards. I remember my early visions of growing a garden that would rival my grandmother’s.

A few weeks into isolation, I tell my partner that this is the peace and quiet we’ve always needed, but then I become sad, restless, worried. There is too much death, too much illness. Too much fear. But planning our meals around the grocery deliveries becomes a pastime. Searching for hard-to-find items becomes such a large part of this new existence.

This is how our days go: Planning meals. Ordering groceries. Zooming. Writing. Chatting with family. Binging on television, the news. Watching the illness engulf the world. Receiving a grocery delivery is a concert, a happening, like going to meet friends at a restaurant or a coffeehouse. “Andre forgot our spring water,” I might say. Or “Yessica did a great job this time.” We rarely have the same delivery driver on the app, but still they are all somehow familiar. One day, I stand in the doorway when a young Black woman is climbing back into her car. I see the tottering heads of her children. “Thank you,” I say and wave from the doorway. When she gets back inside the car, I say, “Baby, where’s your mask?” She waves it out her window like a flag. I am grateful. I am glad to see she chose prime cabbage and apples and nectarines for us. “She was good,” I tell my partner. “I hope she stays safe.” The kids. I think about the kids. Hers. Mine.

My own four children are across town, but I don’t see them often. Sometimes, I speak to my son through a window or he comes and sits six feet away from me on the porch. One daughter dons her mask and walks with me around the block on my birthday. Another one stops by for a few minutes with her children, ten and eleven, and visits with us on the porch. Her boyfriend stays in the car. We see our third daughter every Saturday when she drops off the nine- and four-year-olds while she works. Two of our daughters work in the healthcare field.

My youngest daughter tells me she has leveled a place in the backyard of the duplex she lives in for a garden. She tells me she is doing this because of a breakup. She tells me she is lonely. She tells me she wants to be able to grow her own food while she works from home. She has assembled wooden frames and filled them with dirt. She has small pots of seeds growing all over her house and she sends me so many photographs and texts that it is sometimes annoying, but mostly I am jealous. Her twin sister follows suit in another part of town and tills a three-foot path behind her garage. She sends me pictures of her progress, too. They plant sunflowers, peppers, garlic, carrots, cilantro, basil, tomatoes. They have no idea what they are doing, but they have learned so much from watching YouTube videos. I am amazed. I am reminded of my grandparents’ gardens. My grandmother’s garden sat conveniently behind the house, and my grandfather’s garden sat up on a hill more than 100 yards away from the house. My grandfather grew corn and had huge beds of lettuce that he covered in white fabric during early spring to protect it from the frost. My grandmother grew things she cooked often: squash, tomatoes, potatoes, beans. Although they were protective of their individual gardens, they also helped each other. Growing vegetables was both pleasure and necessity for them. Pride. As Black country folks they grew vegetables on the land that had been in our family for more than a hundred years. This food carried us all summer and throughout the winter. Corn was frozen. Beans and tomatoes were canned. Potatoes were laid out on newspaper in the darkness and coolness of the attic and were enjoyed all winter.

During this pandemic, I complain about the lack of toilet paper and disinfectant, align myself with everyone else in America and head to the internet to play find-and-seek. When I find toilet paper that costs a mint, I jab my fist into the air in celebration. When I find hand sanitizer at a California cosmetics company, I dance. I place my orders. Locally, we have a network that boasts of finding flour, which is scarce, and I finally feel like I’m winning.

Because of our comorbidities, we don’t go out, but our friend Emily says she will pick up flour for us. My partner talks to Emily and answers her questions about the small order we have placed. I don’t want her to be in the grocery store for too long for fear that she’ll get sick. “Tell her to get what she can find,” I say, “and get out of there.” I watch out the window for Emily so that I can wave “thank you” to her when she delivers the goods, but she’s stealthy and I miss her. Emily doesn’t bake or cook. I laugh so long my sides hurt when my partner hoists the twenty-five-pound bag of flour into the house like a prize. Emily has unleashed my inner B. Smith baking ambition. I Venmo Emily reimbursement.

Inspired by the large bag of flour, I order bulk yeast online from France. When it arrives, I begin to bake.

Rustic bread.

Crusty bread.

Banana bread.

I order a Pullman loaf pan. I order a bread slicer and plastic bags and ties for storage. I bake bread every two or three days. My kitchen smells like all the bakeries we will not allow ourselves to go to. My kitchen smells like my grandmother’s kitchen. I am using my kitchen in everyday ways like my grandmother did, and I imagine her beside me when I wipe my hands on my apron or lean in to beat something by hand or to knead dough. My bread rises in a yellow bowl she used.

Homemade Sandwich Bread

(for the Pullman loaf pan)

3 ¼ cups flour

1/3 cup sugar

1 packet active dry yeast

(or two tablespoons bulk yeast)½ cup warm water

½ cup milk (try buttermilk)

1 stick butter

1 teaspoon salt

3 eggs (room temperature)

Preheat the oven to 375 degrees and grease a large loaf pan. In a small bowl or measuring cup, mix the yeast, sugar, and warm water until the yeast dissolves, and let it foam for ten minutes. Heat the milk and butter in a saucepan until the butter melts. Set aside and let cool to lukewarm. In a large bowl, mix the flour and salt. Add dairy mixture to the flour and salt mixture. Beat eggs into the yeast, sugar, and water mixture. Mix everything together to make a stiff dough. Cover and let rise for 1 ½ hours. Shape dough into a loaf and slide it into the greased Pullman pan. Let rise again until it peeks above the rim of the pan. Bake at 375 degrees for 45 minutes or until the loaf springs back upon being pressed. Allow to cool and then slice.

I make a vegetable pot pie.

I make homemade pizza.

I make small loaves of fruit bread that I leave on the porch for my children.

“That one has pecans,” I say. “This one has craisins.”

And I slip inside the house before my desire to hug them overwhelms me.

In April, we hire Trevor, a first-year college student, to cut the grass. I am sorry that I can’t take him a large cup of ice water like I usually would on a warm day. He picks up the debris in the yard. I ask him if he knows anything about gardens. I stand six feet away from him, but when he wipes his brow, I wonder if he’s been safe. He shrugs and says, “My dad does.” I smile and miss my own children enormously.

“If I am going to write,” I declare to my partner, “I need a backyard that is soothing.”

We hire someone to paint the house. The house hasn’t been painted in the twenty years we’ve owned it. We hire someone to build a wooden fence in the backyard.

My girls brag about their growing gardens. They are amazed at what they’ve been able to accomplish. My son is in a mowing war with his neighbors. They race every week to be the first to cut the lawn. Flowers planted by previous renters grow along his sidewalk. His neighbors have grown a variety of peppers and tomatoes in the front yard, planted deliberately in plain sight. My son thinks his neighbors are odd. He sends me photos of their front-yard garden and it is beautiful. “You should do that,” I tell him. He says he doesn’t have time.

I order a free-standing garden planter. I order Cherokee Purple and Amana Orange tomato seeds. I order squash seeds. I grow my tomato seeds in small cups on my windowsills. My partner assembles my standing planter. Another friend, Story, an urban farmer originally from Appalachia, drops off begonias, mustard greens, and cherry tomato plants on my porch. My partner and I pick up dirt from a garden supply store and are relieved when they bring it to the car and put it in the backseat for us. I fill the planters and poke my baby plants into the black dirt. In a few weeks, my patio is dotted with small pots filled with tomatoes and squash; my standing planter is thriving. I am depending on some ancient DNA to kick in and make me remember how to do this; placing my hands in the dirt makes me closer to the ancestors.

A few weeks later, I order slate rock from a landscape company and it is delivered in a large truck. After watching videos and being inspired by an artist friend’s Instagram photos, my partner and I design a rock garden against the newly built wooden fence using slate rock for cover and broken concrete as border. We carry the rocks to the backyard in small buckets and work until our backs are sore. We stop to rest but keep to our work. I plant Hosta shoots that I’ve ordered online and bring the large Buddha statue that had previously sat in the corner of our bedroom to the center of the garden. I order lights.

Our labor has produced a peaceful space, but it’s too hot to sit on the patio and write—and the mosquitos have taken over. I admire the glow of the lights at night and delight in all the plants I’ve placed in the ground and how they’ve grown. I am reminded of moonlit nights in my grandparents’ backyard, hulling and snapping beans or shucking corn.

Inside the house, Ron cleans the kitchen. I am a messy baker. I spend days poring through recipes written on pieces of paper and stuffed in the flowered metal container I’ve had since high school. Some of them are written in my grandmother’s perfect script. I cook. He cleans. Repeat.

Outside, my garden is doing poorly. My squash fans out beautifully with dark, wide leaves, then turns a lighter green, then yellow. A few days later it turns brown, and the entire plant dies without ever bearing squash. My tomatoes and peppers are covered in white aphids, and I feel as though I have disappointed my ancestors. I spray the aphids with a mixture of dishwashing liquid and water, and that holds them off long enough for my plants to bear small, misshaped, subpar fruit. While my tomatoes taste good, it feels only partially satisfying to have grown my own food. Maybe I’ve lived in the city too long.

My cousin and his wife own Miller Farm, which is in Stanford, Kentucky, about thirty minutes from where I grew up, forty miles from where I live now. Another cousin who drives to Lexington weekly volunteers to deliver produce from the farm when I ask. I order one of their “nutrition baskets” from my cousin’s wife, Susan. The nutrition basket comes in two containers holding squash, peppers, runner beans, beets, carrots, and onions, as well as yellow, red, and green tomatoes. I fondle the tomatoes and take a bite. Delicious. The burst of sunshine I remember from my childhood. When I ask Susan what kind they are, she says that they are an heirloom tomato called Ox Heart. “The seeds are passed down from generation to generation,” she says. “My mama will never let them die out.” I tell her that me and her husband’s grandparents grew Big Boy tomatoes and that they also kept the seeds. “Ask George Allen if he remembers . . .” I say. My grandparents sifted through the flesh of the last fruit of summer, collected the seeds, dried them out, and placed them in jars to save for the next planting. I think about the tomatoes I ordered and where the seeds originated. Of course, I have no idea. I think of Ox Heart. I think of the animals on our farm. I think of cow hearts, of horse hearts, of pig hearts. I think of how our grandparents were the heart of our family and how each of us are still carrying on their traditions in large ways and small even after all these decades.

My partner orders a turquoise freestanding mixer and a shiny silver immersion blender for me, and I am on fire in this kitchen. I am a contemporary fully equipped version of my grandmother.

I mix Miller Farm’s gorgeous Ox Heart tomatoes with a few of my scraggly ones.

I’ve always been a good cook, but these months of isolation have made me revel in preparing a meal. I’m slow, methodical. Much better than I used to be but still always

reaching back.

I make tomato soup.

Crystal’s Tomato Soup

4 large tomatoes (more if you are

using smaller ones), roughly chopped1 onion, chopped

fresh basil, chopped

1 cup heavy whipping cream

½ stick butter

1 quart chicken stock

2 tablespoons flour

salt and pepper to taste

In a large pot, sauté onion in butter until soft and clear. Add tomatoes. Let it all cook down until the tomatoes are tender. Add the chicken stock and let it cook for about 20–30 minutes to mix the flavors and reduce the liquid. Take the immersion blender and get everything smooth. Bring the mixture to a low boil. Meanwhile, in a measuring cup or bowl, add the 2 tablespoons of flour to the cup of heavy cream and mix until there are no more dry spots of flour. Slowly pour into the boiling mixture and stir quickly so it doesn’t clump up. Simmer to desired thickness. Add the chopped basil right at the end and then eat up. (You can leave out the basil for the kiddos.)

I make root vegetable soup.

I worry and cook in the confines of my kitchen just like my grandmother did.

My kitchen is small and clean and cluttered.

I order vegetables from my cousins’ farm for several weeks during the summer. It feels good to wash the dirt off the beets, to have less packaging and waste. I feel closer to where I come from when I do this. I cook. I remember. I wash. Slice. We still have to order groceries, but the fresh vegetables give me a feeling of being more connected with my ancestry. It feels right to smell dirt on the food we eat.

When I call my daughters, they tell me about their gardens. One asks me how to get her sweet potatoes out of the ground. “The little shovel didn’t work,” she said. And I laugh because I know she’s talking about a garden spade. “They are deep down in the earth,” I tell her. “You need a hoe.” The other one asks me what she is supposed to do with so much cilantro. I talk a long while about what she can make with the harvested cilantro and other options she will have once the plants turn to seed. I tell her she can harvest the coriander seeds from the plant and grind them for pickles or for her spice rack. “I didn’t grow up with cilantro,” I tell her, “but I love it.” She sighs as if what I’m saying sounds like too much work. “I am much more interested in planting and watching it grow than harvesting it,” she says. “I just wanted to know if I could do it.” I tell her that sounds wasteful and that she has a duty to tend to what she’s planted. I tell her that it is in her blood.