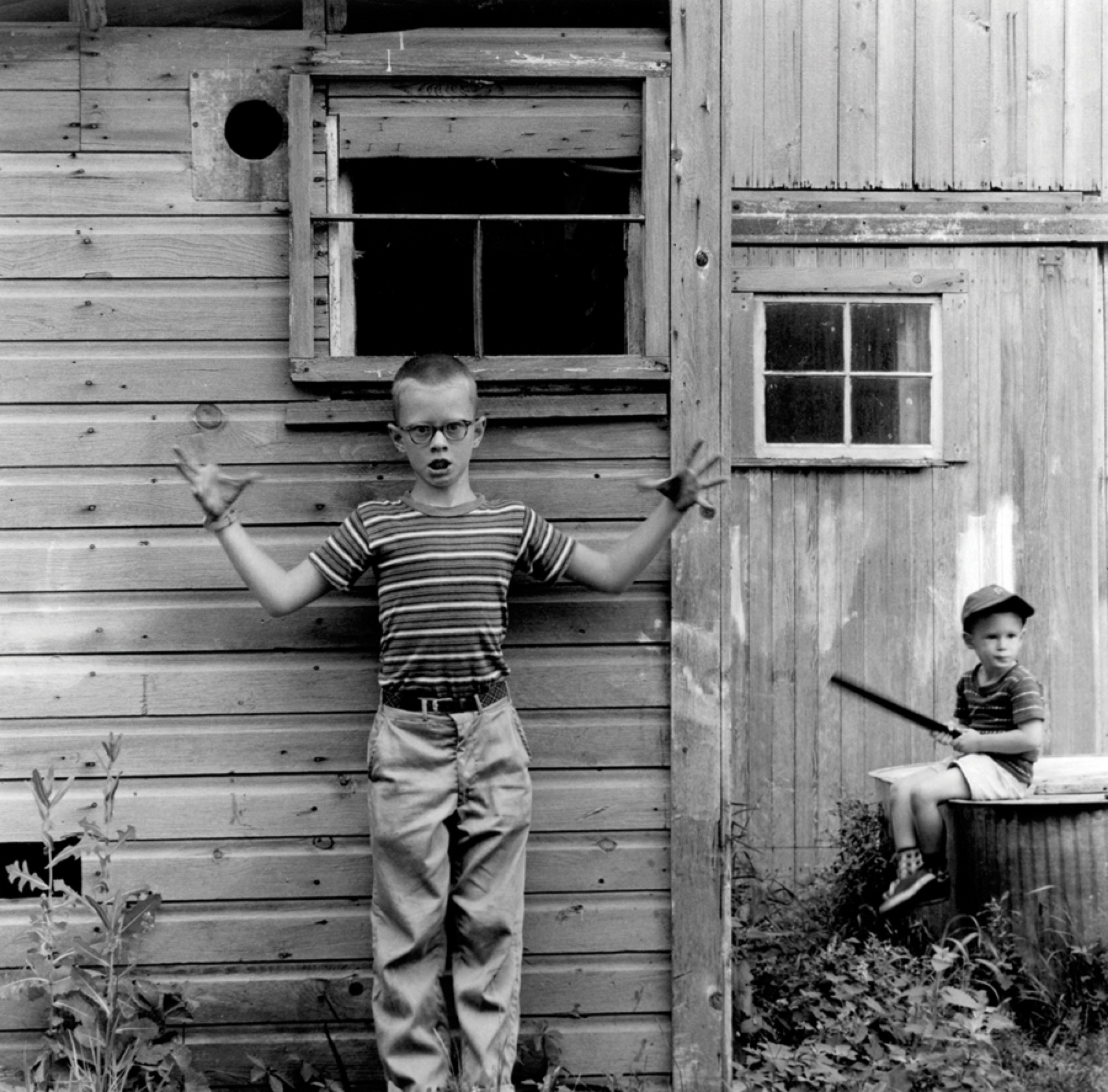

"Untitled, 1960" by Ralph Eugene Meatyard,© The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The Adaptation

By Theodore Ross

When Steven Spielberg brought Raiders of the Lost Ark to America’s movie theaters in 1981, he unwittingly helped give birth to a generation of child filmmakers. Boys and girls around the country began casting themselves not just in the role of the movie’s swashbuckling archaeologist, Indiana Jones, but also its baseball-capped, blockbuster-blessed director. Spielberg’s boyhood 8mm efforts were well-known, and it felt like anyone could replicate his achievements. If you grew up during this period, you may have attempted your own homespun cinematic effort, captured, quite without steadi-cam, on dad’s first-generation camcorder. If not Raiders, perhaps a three-minute Star Wars tribute, with wooden spoons for lightsabers, a grumbling sibling unhappy to be cast as R2-D2, and a nine-year-old Skywalker who can’t remember his lines and mugs his white-belt karate moves for the camera.

In 1982, three schoolboys from Mississippi set out to remake Raiders of the Lost Ark, and they didn’t stop remaking it until it was done, seven years later. They were Chris Strompolos, a potbellied and unexpectedly charismatic Indiana Jones; the director, Eric Zala, Strompolos’s power-nerd counterpart, who also played Belloq, Indy’s nemesis; and Jayson Lamb, a quirky Bible Belt vegetarian, Buddhist, and sometime nudist, who was the cinematographer, makeup artist, and special effects master. Their film, Raiders of the Lost Ark: the Adaptation, bears no resemblance to most other childish film endeavors, begun and abandoned over the course of a school holiday, if not an afternoon. Theirs is an act of creative ingenuity, a feat of endurance, a testament to a childhood era free of supervision and scheduling. It is a movie.

In Raiders! The Story of the Greatest Fan Film Ever Made, Strompolos and Zala, assisted by a writer named Alan Eisenstock, tell the story of The Adaptation with archaeological flair, which is only fitting. The deeper the book delves into the details of the movie the more the production astounds. Zala storyboards the entire film: 649 separate shots, all hand-drawn. Lamb reverse engineers, by instinct and without guidance or education, techniques that range from proper lighting to blood squibs to exploding gunfire. The boys have no access to shooting scripts, so they sneak into screenings of the real Raiders to surreptitiously tape it and then transcribe the lines. Strompolos was removed from one theater when his equipment was discovered.

They talk their way into the use of both a battleship and submarine for location shoots. They need a desert for the Tanis dig scenes in the Sahara, so they convince a man named Bo Jo Fleming, owner of a rural “dirt farm,” to allow them to film on his property. Downtown Gulfport, Mississippi, is dressed up convincingly as downtown Cairo. They construct sets on the Zala family’s sprawling and ramshackle antebellum mansion on the beach in Ocean Springs. They replicate Indiana Jones’s house in one of its bedrooms, and Belloq’s tent in its living room. They craft a replica of the Well of Souls, complete with an Anubis made from a rusted-out water heater, plastic sheeting, and other castoffs, in one of its two basements. The other is transformed into a Nepalese bar that they gleefully burn to the ground. Young Zala is doused in gasoline and set alight for a stunt during the fight scene there, resulting in the first of several Raiders-related injuries and hospitalizations.

They have a vintage Bentley, a truck with its engine removed, a skiff whose motor ends up at the bottom of the Tchoutacabouffa River, and an airplane. An artisan custom-builds them a six-foot-high fiberglass boulder, the last in a series of failed attempts to re-create the giant rock that chases Indiana Jones at the beginning of the movie. It’s so big they have to buy two telephone poles to use as a track on which to roll it. (Boulder calamities are a running source of amusement throughout Raiders! An early effort, built in Strompolos’s bedroom, seems promising until they realize it’s too large to get out of the room; a weather balloon covered in papier-maché deflates; a chicken-wire ball is lost in a storm.) There are live snakes, fake tarantulas, an obedient dog for the Egyptian Nazi-monkey, a whip, and lots of guns, some of which fire live ammunition, though not during filming, with the exception of the shotgun used to simulate the explosion of Belloq’s head, made from a plaster cast, during the climactic scene when the Ark is opened. A problem casting Zala’s face sends him to the hospital and costs him his eyebrows.

The boys enter into and pass through puberty onscreen, and the costumes, camerawork, special effects, and their acting chops improve as they age. Strompolos is paunchy, blockish, and short. In the early stages of filming, his voice is a child’s squeak, and they smear ashes on his face to simulate stubble. Yet he is remarkable as Indy nonetheless. He exudes a jaunty, camera-ready bravado as he is dragged behind a moving truck, fighting pimple-faced Nazis. He works his whip with aplomb, looks like he was born in Indy’s leather coat and fedora, and has real chemistry with the towheaded punk-rock chick who plays Marion. Their onscreen kiss, we learn, is the first of his young-adult life.

None of the others are what you would call natural actors, but they are no less memorable for being laughable. The plump, white fourth graders who play the Hovitos Indians are cuter than they are menacing. Sallah, Indy’s Egyptian friend and fixer, has a twanging Mississippi accent and a skateboarder’s hairdo. Several children appear as Nazis, Nepalis, and Egyptians. It only adds to the movie’s baffling charm.

In Raiders! Zala and Strompolos discuss the child they cast as Toht, the sadistic Nazi. They call him a “slob” who lacks the “creepy energy,” “menace,” and “sense of danger” of the original actor, and only allow that he is “appropriately round” enough for the role. A harsh assessment, and perhaps it is true. But then again, I was only ten.

My memory of how I became Toht differs slightly from what’s in the book. In Raiders! Chris describes me as underwhelmed at being cast. “It’s so boring in the summer,” I am supposed to have said. “At least now I have something to do.” This isn’t exactly accurate. In fact, I was thrilled. Joining the cast played to my ego—I didn’t know I couldn’t act—but more importantly, it afforded me a higher rank in the film’s hierarchy than that of my bullying older brother, Jason, who was classmates with Chris and Jayson, and who was only allowed to help with the camera and play various bit roles.

Still, I was permitted to rise only so high in the film’s heroic firmament. Toward the end of the Nepal fight scene, as the bar is engulfed in flames, Toht stumbles onto Marion’s amulet. He grasps it, realizing too late that it has grown searing hot from the fire. Screaming, his hand smoking as the amulet burns him, he rushes from the bar, crashing through the door headlong, to thrust his hand into the Himalayan snow. I was, as a fifth-grader, deemed capable of reading my lines, if badly, having a red-hot poker whipped from my hands by Chris (gamely, he gave me a couple of lashes as well), and igniting the gasoline on the bar. But the leap through a burning door was, apparently, a stunt too far. Chris claimed that morsel of glory for himself, donning my costume and bounding into and beyond the inferno. He nailed it in one take.

One thing Raiders! conveys nicely is how we instinctively inhabited the stereotypes of Hollywood culture. Jealousy and rivalries ran rife among the cast and crew. There were swollen egos and bruised feelings, virginities lost, joints smoked—all of it pint-sized, pubescent, and taking place in Mississippi. Chris, like all leading men, won the affections of his female co-star: he had something going with Marion, as was his due. (“Between takes, Chris and Angela flirt like a cliché of leading man and leading lady . . . . When they’re not groping each other, they pause for a smoke.”) The production was nearly derailed when Eric discovered Chris sneaking around with his girlfriend. Jayson felt taken for granted, the plaint of every “below the line” crew member who ever lived. He seethed when a local TV reporter came to interview the boys and he was not apportioned the credit he deserved. Eric grew dictatorial, in part because he held authority over so many people, but also as a point of distinction between him and Chris, his best friend and foil. (The book, in many ways, reads as a platonic love story between the two; they are forever grabbing each other in an emotional embrace.) Eric knew that Chris drew people to the production. We came to be around him, because he convinced us it would be fun, because he was fun. But Eric also knew that we stayed because he kept us organized, gave us purpose. If he could not be loved he would be respected. He bought himself a megaphone, which he used with great gusto. (“So, you’re saying everyone hates me?” “Not everyone,” Jayson says. “We’re saying dial it down. Don’t scream so much,” Chris says. “Anything else?” Eric asks, trying not to look upset. “Yeah,” Chris says. “Bury the fucking megaphone.”)

We spent seven years working on The Adaptation. Because it took so long, everything we did, from the stunts to the sets to the locations to the fundamental act of making a movie, seemed normal. It consumed too much of our adolescence and teenage years to feel otherwise. Yet we also understood that we’d done something extraordinary, or at least larger in breadth and ambition than anyone we knew had even attempted. Greatness beckoned; this was self-evident to all of us. We even joked about it, in the way you laugh at something in order to hide the fact that you really believe it. People would look back at us and say, The talent was always there, just waiting to be discovered.

When The Adaptation was complete, Chris’s mother organized a “premiere” at a bottling factory in Gulfport. We wore black tie. Chris and Eric made speeches. The TV and newspaper people came. Everyone applauded. And that was it. There was nothing left to do but move on—to college, other cities, different episodes in our lives. Eric went to NYU’s film school. Chris struggled for years as an actor and musician. Neither found much success. Eventually, both gave it up.

I lost track of Jayson and Eric but remained close to Chris. We shared an apartment in Los Angeles in the mid-1990s while I was finishing college at USC. We never spoke about the movie. We didn’t mention it to our girlfriends, and when we both got married, we didn’t mention it to our wives. We never watched it. For many years, the only time I’d ever even seen it was at the premiere in Mississippi. The Adaptation was just something we did when we were kids; if greatness was indeed our due, we no longer believed it would spring from the movie.

Then, in late 2002, that all changed. Eric had apparently taken the movie with him to NYU. Copies of it circulated, even among people who had no connection to him, even after he graduated in 1992. It became a sort of film-school urban legend, a bizarre filmic tribute made by a group of anonymous children. A young director named Eli Roth got a hold of the movie at some point and brought it with him to Butt-Numb-a-Thon, the vividly named film festival in Austin, Texas, run by movie blogger Harry Knowles. Roth convinced Knowles to screen the movie during some downtime at the festival, and when he did, the audience was captivated. Knowles wrote about it on his website, Ain’t It Cool News, calling The Adaptation “pure magic” and “the best damn fan film I’ve ever seen.” Roth’s first movie, Cabin Fever, was soon to be released, and his career was taking off; he passed the film to an executive at Dreamworks. The executive gave it to Steven Spielberg.

And then, in a scene drawn from our deepest childhood fantasies, Steven Spielberg watched our Raiders and thought it was good. He sent a letter to Chris, Eric, and Jayson. He thanked them. They were, he wrote, “hugely imaginative,” with “vast amounts of imagination and originality.” “I’ll be waiting,” he added, “to see your names someday on the big screen.”

I had been living in Los Angeles off and on since I graduated high school. After college, I wrote a version of the Great American Novel that will never be published. I went to graduate school at USC, in writing, switched to screenplays, and was flailing about on the periphery of the filmmaking industry, answering phones and making copies at different Hollywood talent agencies. Chris worked as a manager for a DVD remastering outfit and had abandoned his efforts to break into acting and singing. Eric had made an earlier foray into the L.A. life, after film school, but he’d left when he, too, failed as a screenwriter. He lived in Orlando, working for a video game company. He had fallen out with Chris—the book chronicles with scrupulous detail their various fights and reconciliations as children and adults—and they weren’t speaking to each other. None of us had seen Jayson Lamb in years. We were all struggling with our careers, and this moment of belated recognition rekindled the old conviction, which had never really disappeared, that the mere fact of The Adaptation’s existence made our success in Hollywood inevitable. Like so many Americans reared in the Age of Celebrity, we believed we were destined to fame, but our claim was different, more likely, more deserved. We just needed a chance.

That chance came when the editors of Vanity Fair magazine offered to do a lengthy feature about the movie, about Jayson, Chris, and Eric, about us. There would be a photo shoot of the boys, now men, in costume at Eric’s house in Mississippi. The editors decided to have Jayson dress up as me, Toht, for the shoot, although I did ultimately appear in a photo in the article, as a teenager on a camping trip with Chris, identified as “Toht the Nazi torturer, played with evil glee by a baby-faced kid named Ted Ross.”

We really knew nothing about the film business, but we knew enough to know that when the Vanity Fair article came out, all Hollywood would gather around. When it did, we wanted to have something more to show them than just The Adaptation. We needed a new film project, a grown-up one. So we decided to turn the story of our movie into a movie, and in so doing, engineer a remedy for our unrequited professional expectations and desires. We understood that to do so meant to exploit our childhood, to leverage it and the propulsive energy surrounding the unexpected interest in our work. But it didn’t matter. It was meant to be.

Without thinking, we settled back into our youthful moviemaking rhythms. Turning our childhood movie into a movie about our childhood required a screenplay, so Chris, with the same self-starting spirit he had brought to The Adaptation, set out to write it himself, freehand, in a notebook. That notion soon proved unworkable—let’s just say he’s as much of a writer as I am an actor—and again he sought a partner. With Eric in another city, he came to me, and soon Chris and I were co-writing, using my computer. Co-writing soon became me writing, with a friend from graduate school as my writing partner. Eric and Jayson both agreed to this arrangement, although they wanted to be included in the process. Chris and I flew them out to Los Angeles for a long weekend, to talk about the old days, cover any stories I didn’t remember, and make sure we got everything right.

We decided to videotape our conversations. None of us had any money, so the cameraman was a friend, but a professional nonetheless: he worked for the pornographic movie director, producer, and sometime star Seymour Butts. He also snapped some naked stills of Jayson, at his request. Chris scheduled a chat with two powerful entertainment lawyers who might represent us once a deal was offered. They came highly recommended and relatively cheap; their offices, if that’s the right term, were in a houseboat moored at Marina del Rey. Neither wore shoes, which I felt only made them seem more successful. I took my own meetings with several literary agents. I remember trying to describe my longer-term creative ambitions to one agent when he interrupted me mid-sentence, saying “You know what I want? I want to make money! Money!” I hired him.

It was thrilling to be with one another again, and the deadline pressure of the Vanity Fair article, the launching pad it signified, only added to the excitement. The buried seeds of the talents we’d developed as children were now finally going to bear fruit. It didn’t happen, of course, though I did finish the screenplay in time for the article, working with Chris and my partner on an almost daily basis. Only problem was that it wasn’t any good. Eric and Jayson, in particular, hated it, not just for its flaws of storyline and language, but because it reflected our old resentments and competitions: it focused too much on Chris (he was our Indiana, after all) and too little on their lives and contributions. Producers now, they demanded revisions, gave notes, made suggestions: but there was no time and I refused to implement them. If there was no script to coincide with the Vanity Fair piece, what was the point? That was the end of our partnership.

Eric, Chris, and Jayson still had something to sell, though, and “Raiders of the Lost Backyard,” a “tale of love, obsession, and pissed-off moms,” appeared in the March 2004 issue of Vanity Fair. Soon after it was published, Steven Spielberg invited Eric, Chris, and Jayson to his office. This was a great and strange and baffling thing, as all of us, every child who participated in the movie in whatever capacity no matter how small, always imagined—no, always knew—that it would happen someday. They chatted with the folks at NPR and Craig Kilborn and Today. Variety reported that they sold their “life rights,” in a “deal worth mid-six figures,” to an important producer named Scott Rudin. He intended to turn their story into a movie for Paramount, the studio that made the original Raiders.

Before the sale to Rudin, I met Chris at a Starbucks on Sunset Boulevard. I asked for the meeting, though I don’t really know what I hoped it would accomplish. Without Eric and Jayson’s cooperation, which I wasn’t going to get, no one was ever going to use my screenplay. Chris was sympathetic, but he told me there was nothing he could do. “I have to stick with the Triad,” he said, steepling his hands into the shape of a triangle. “The Triad” was his new term for him and Eric and Jayson. “We have to stick together and see where this goes.”

A few weeks later, I took a temporary job at the lowest rung of entertainment-industry servitude, as a “runner” at a talent agency. I spent my days copying scripts and other documents and literally running them to whichever agent or manager had requested them. One day, I received an order for the day’s “breakdowns,” the industry’s list of open writing, directing, and acting assignments. My eye stopped at the one for The Adaptation. The agent noticed me staring, and he told me the story of this crazy movie these three kids in the middle of nowhere had made. Amazing stuff. He had a couple of writers who would be perfect for it. One of them, he said, had made his own film as a boy, a ten-minute thing about vampires or something.

I’ve followed Chris and Eric’s progress over the years on the Internet, so I know that after the Vanity Fair article, they quit their jobs to focus full-time on their movie careers, though they returned to work later. (I tried to interview them both for this story. They agreed, but asked me first to send them a list of questions via e-mail. A few days after I did, I received a short e-mail response from Eric. “We’re not sure what your real agenda is,” he wrote, “but, respectfully, we’re going to decline to participate.”) They founded a production company, Rolling Boulder Films, and are at work on several projects unrelated to Raiders, but no movies as of yet. In a sense, they have become professionals at being the “guys who made that movie as kids.” They’ve done hundreds of interviews, put together the book, and traveled the country giving lectures and showing the film. They have loyal fans, including one woman I came across online, who, when I told her who I was immediately wrote back, “Eek!!! Mini-Toht! I must begin stalking you immediately!” Once she learned that I was no longer friends with Eric and Chris, however, she said no to an interview. “What is your story about and what is your intention on how it is to be portrayed?” she asked, adding before I could respond, “Whatever you answer, YOU WERE AMAZING AND ADORABLE as Toht! And you can print that!!!”

Recently, my son turned seven and I figured he had grown old enough to appreciate what we had done. First, I showed him Raiders, which he liked somewhat. By today’s action-film standards, it moves a little slowly; there are no computer-generated enhancements, and Harrison Ford’s grinning flirtations with Marion passed over his head. The melting faces were cool, though, as were the various fight scenes, particularly the one in which the guy gets chopped up by the airplane prop (alas, the only moment from the film we didn’t shoot). Then I showed him The Adaptation, after first explaining that I had helped make the movie as a boy. I told him how long it took, and how hard we had to work, and about the satisfaction of seeing it through to the end. Sadly, the movie failed to impress: it was too dark (bad lighting); he couldn’t hear anything (bad sound effects); everyone’s voices sounded funny (he’s grown up in New York; Mississippi accents are weird); and the whole thing looked fake (Even the boulder? Yes, even the boulder). I let him turn it off midway. “No videogames,” I told him as he scampered off to his room.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.